Research and teaching aside, the Department has also contributed to the creation of many new programmes and centres on campus

Times were tough for IISc in the 1930s. It faced a serious cash crunch – income from both the Mysore Government and JN Tata’s Bombay properties had dwindled. World War II was looming on the horizon. Criticism was growing that the Institute was focusing too much on “pure sciences” like physics and biochemistry, and doing too little of the applied research that Tata had originally wanted. Courses in engineering other than electrical engineering were “completely ignored in the early life of the Institute,” according to Sir M Visvesvaraya, former president of IISc’s Court.

To rectify this neglect, a Joint Committee of the Council and Court members was set up in 1940. This committee recommended, among other things, the establishment of a central workshop that would deal with “problems of design and construction of industrial plants for various manufacturing processes.” It also suggested that “as soon as funds become available, a Department of Mechanical Engineering be established at the Institute.”

ICE and PE – the latter had a separate Mechanical Engineering section – merged into what is now the Department of Mechanical Engineering

But the Department wasn’t set up right away – even though related courses like applied mechanics and hydraulics, and heat engines were taught to students as early as in the 1930s. Its forerunners were the departments of Internal Combustion Engineering (ICE) and Power Engineering (PE) – the latter had a separate Mechanical Engineering section – established around 1945-46. These two merged into what is now the Department of Mechanical Engineering (ME) during the 1970s.

Over the past 75 years, research at ME has spanned a wide range of areas, from engines, foundry and heat transfer to more recent interdisciplinary explorations such as robotics and biomechanics. Its faculty members have led and participated in national and international initiatives related to energy, acoustics and design. At home, they have also helped establish many of IISc’s departments and centres, including Sustainable Technologies, Product Design and Manufacturing, Nano Science and Engineering, Energy Research, BioSystems Science and Engineering, Continuing Education, Industrial and Scientific Consultancy, even the JN Tata auditorium, points out GK Ananthasuresh, faculty member and until recently the Chair of the Department.

“Our department has been a quiet force, but I would also call it quite a force,” he says. “It has had a tremendous impact on the campus.”

Engines and energy

The impact of World War II on the Institute was enormous. “The War that is going on,” Visvesvaraya once announced to the IISc Court, “is a mechanical engineer’s war.” Industry-relevant research got a shot in the arm, and new courses on aerospace engineering and metallurgy were added. A new Department of Internal Combustion Engineering (ICE) was also set up in 1945, in the building that now houses the Society for Innovation and Development, and Major BC Carter was appointed to head both ICE and the central workshop.

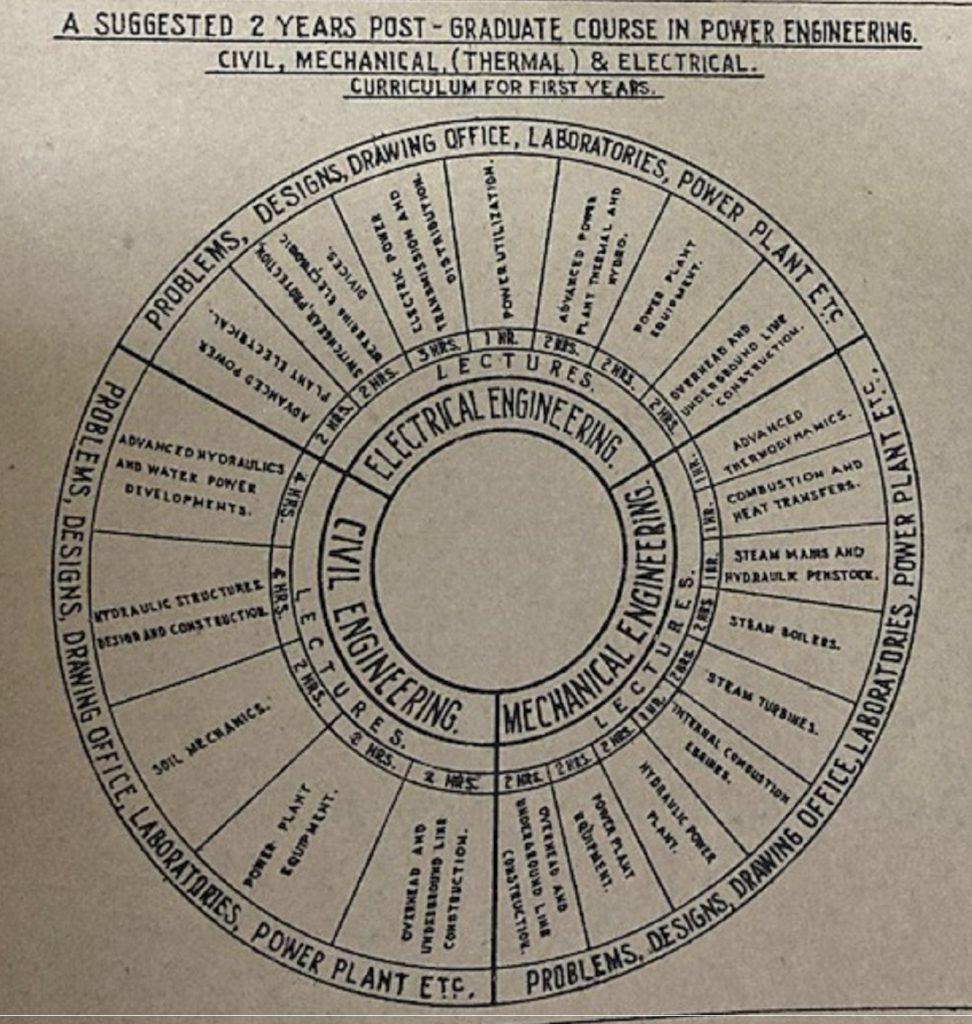

During the early years, ICE researchers extensively tested and designed various types of engines and their components, working together with industry partners on collaborative projects nurtured by the newly formed Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). Around the same time that ICE was set up, a new Department of Power Engineering (PE) was also established, to support the electrical power projects that mushroomed across the country after the war. Its foundation stone was laid in 1947 by former Cabinet Minister Syama Prasad Mukherjee, and the building was inaugurated by Rajendra Prasad, the then President of India, in 1951. MS Thacker, who would go on to become IISc’s Director, was appointed its first head. A few years later, it was bifurcated into an Electrical Engineering and a Mechanical Engineering section.

building in 1951 (Photo courtesy: IISc Archives)

From the early days, the emphasis on hands-on learning was heavy. Students built equipment and machines that they needed for their projects on their own in the workshop. A full-fledged thermal power station was also set up on campus to train students in operating and maintaining it round the clock.

In 1950, Arcot Ramachandran joined IISc as an assistant professor, and later became the head of the Mechanical Engineering section. By all accounts, he was a trailblazer. He kick-started research on heat transfer and thermal sciences, which helped spawn major programmes on energy research across the country. He was also an exceptional administrator who is said to have introduced many new programmes and courses like nuclear engineering and machine design. “The Department owes a lot to Arcot Ramachandran,” says J Gururaja, a former student who also worked with Ramachandran in later years. “He was always looking beyond the current state of affairs at that time: What new branches can there be? What new areas can we start? Who were the competent people available?” Ramachandran was even tipped to become IISc’s Director – Satish Dhawan was eventually appointed – before moving on to head IIT Madras, and later the Government of India’s newly established Department of Science and Technology (DST).

To this day, heat transfer and energy research – which Ramachandran pioneered – continue to be an important part of the Department’s focus. More recent research has focused on thermo-chemical storage, combustion and spray research, refrigeration technologies and heat management in spacecraft systems. Many ME faculty members also helped establish and continue to be associated with the Interdisciplinary Centre for Energy Research at IISc, which is pursuing innovative research on solar power, supercritical carbon dioxide-based power generation, and clean coal technologies.

Changing directions

A few years after Ramachandran left IISc, the Department’s focus shifted. In the early 1970s, Dhawan brought LS Srinath, the head of the Mechanical Engineering Department at IIT Kanpur, to IISc and tasked him with merging ICE and the ME section into a single Department of Mechanical Engineering. “He [Srinath] was interested in creating an integrated approach to mechanical science. That is how the division [of mechanical sciences] was founded and he became the first Chairman,” says Gururaja.

Soon after the merger, the Department became involved in a crucial social experiment. In the early 1970s, science and technology institutes in the country were severely criticised for not doing enough to address rural problems, and for focusing solely on urban challenges. Faculty members at IISc, including many from ME, lobbied the Institute administration, and as a result of their efforts, the Cell for the Application of Science and Technology to Rural Areas (ASTRA) was set up in 1974. It mobilised the development of many rural technologies – biogas plants, low-carbon housing, and small-scale fertiliser industries, to name a few. Several extension centres were also set up in villages near Bangalore to train local people to become self-reliant. Many of ASTRA’s early initiatives were assigned as ME student projects. ASTRA later evolved into the Centre for Sustainable Technologies, which continues to work on rural development.

Faculty members at IISc, including many from ME, lobbied the Institute administration, and as a result of their efforts, ASTRA was set up

Similar to ASTRA, another initiative called SuTRA (Sustainable Transformation of Rural Areas) was led by former faculty member Udipi Shrinivasa in the 1990s. It was created as an independent programme unit under IISc’s Society for Innovation and Development. The aim was to implement developmental projects in a set of villages surrounding ASTRA’s extension centre in Ungra village, Tumkur district. An important outcome from SuTRA was the development of biodiesel from non-edible seeds including Pongamia. Other projects involved building rainwater harvesting structures, using satellite maps to spot locations for drilling borewells and preserving perishable agro products by dehydration.

(Photo: KG Haridasan/IISc Archives)

Yet another socially-relevant initiative that ME researchers were involved in was the development of microhydel power generators which use turbines to generate electricity. An ultra-low head propeller turbine ideal for flat terrains was developed and installed near Mandya, Karnataka. Several cross flow turbines were also installed in various parts of the country, including Kedarnath and Arunachal Pradesh.

ME also made critical contributions to industry in two key areas. One was the development of cast-iron crankshafts to replace forged crankshafts in automobiles in order to reduce production cost by 30-40%. Another was work on industrial acoustics, particularly on mufflers and silencers to reduce noise in vehicle exhaust, an area pioneered by faculty member Manohar Munjal. He and others in the Department worked on several industry projects related to noise control and vibration, even stealth technologies for Indian Navy submarines and silencers for limiting cockpit noise in a fighter aircraft. Manohar has also advised the government on defining noise control norms and policies, and was instrumental in setting up a research hub called the Facility for Research in Technical Acoustics (FRITA) at ME in 1998. “He defined technical acoustics for the country,” says Ananthasuresh.

New designs

Back in the 1930s, as the Institute was struggling to strengthen its financial situation, one of the cost-cutting measures proposed was the setting up of a central workshop “to avoid unnecessary duplication of staff and equipment.” Over time, this facility became especially indispensable for ME students. Many of them would spend hours each day toiling away at the workshop, designing and assembling parts and equipment that they needed for their projects. Manufacturing and design continued to remain an important part of ME, and in 1996-97, the Department started a two-year Master’s in Design programme. This led to the transformation of the central workshop into the Centre for Product Design and Manufacturing (CPDM) with former faculty member TS Mruthyunjaya as its first Chair. CPDM is now deeply involved in developing futuristic manufacturing technologies, including India’s first smart factory platform.

Around the same time that CPDM was launched, IISc also joined hands with Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) to start a first-of-its-kind for-profit venture called Advanced Product Design and Prototyping (APDAP) to provide design services for a slew of industry clients, including BHEL, TVS, GM India and DRDO. Its goal was to take a product from the drawing board all the way up to prototyping, and tying up with industry partners for large-scale manufacture. The initiative was largely driven by faculty members from ME.

Towards the close of the century, research on robotics and autonomous systems also picked up steam. Snake-like robots useful in search and rescue, and surgery; crawling robots to inspect pipes in hazardous conditions, and more recently, touch-based tools to cut tissue and carry out surgical procedures have all been developed. A start-up called Mimyk with roots in ME has also developed an ingenious endoscopy simulator to train medical students and doctors without using human subjects.

(Photo courtesy: Mimyk)

In 2004, with funding from DST, DRDO and the Ministry of Mines, the Department set up a National Facility for Semisolid Forming (NFSSF). A few years later, researchers working in this facility made a breakthrough: they developed an indigenous version of a process called thixocasting. In thixocasting, a metal is heated until it becomes partially liquid and injected under pressure; this makes it less viscous and improves the quality of the parts made from it. The technology has proved tremendously useful for manufacturing light-weight vehicle components, including parts for two-wheelers manufactured by TVS Motors.

In the past few decades, research at ME has become more interdisciplinary. One person who exemplified this spirit was former faculty member Sanjay Biswas. Although originally known for his contributions to tribology, he also pursued research in areas as diverse as chemistry, nanoscience and bioengineering.

“Biswas was also an able administrator who knew how to excite people around him to take new initiatives, and then step aside when things were on the right track, only to move on to another initiative,” his colleagues recounted after his passing in 2013.

In later years, he developed a keen interest in healthcare and began studying the mechanics of cell wall movement and cancer cell adhesion. He wanted to bring about a “radical change” in bioengineering and biodesign in the country. Biswas was among the first to start a bioengineering group at the Institute, bringing together IISc faculty members and medical doctors. His efforts played a pivotal role in the establishment of the Centre for BioSystems Science and Engineering (BSSE) at IISc.

Looking ahead

What does the future hold for ME? “We have a fairly long list,” says Ananthasuresh.

In 2019, as part of an international peer review, ME was asked to assess its strengths and weaknesses, and identify areas where it needed to work on. It became clear that large-scale collaborative efforts anchored by the Department were lacking, more faculty members had to be recruited in core areas, Master’s programmes needed to become more attractive, and industry networks had to be strengthened.

“We hope to see more women coming into the Department as students as well as faculty members”

Ananthasuresh also points out several new research areas where the Department wants to break new ground: simulation technologies, food storage and transportation, automated agriculture, mobility engineering, space robotics and underwater exploration. New and exciting technologies are also on the horizon, he says. “Now we have cell and tissue mechanics, and biomedical devices, but we would like to go beyond that – artificial limbs, for example, that gel well with the nervous and muscular systems, and can integrate with the body.”

Encouraging more women students and faculty members to join what has traditionally been a male-dominated field will also be important. “Right now, I am happy that we have three women faculty members in the Department,” says Ananthasuresh. He points out that the field is “getting redefined in many ways,” and moving beyond the misconception that mechanical engineers only “lift heavy weights and work with heavy machinery.” “Traditional areas like refrigeration and air conditioning, power and heavy machinery have now become more R&D than fundamental research. Newer areas are emerging and more emphasis is being laid on computational modelling. So, we hope to see more women coming into the Department as students as well as faculty members.”

For more stories on the Department of Mechanical Engineering, please click on the links below:

Remembering Arcot Ramachandran