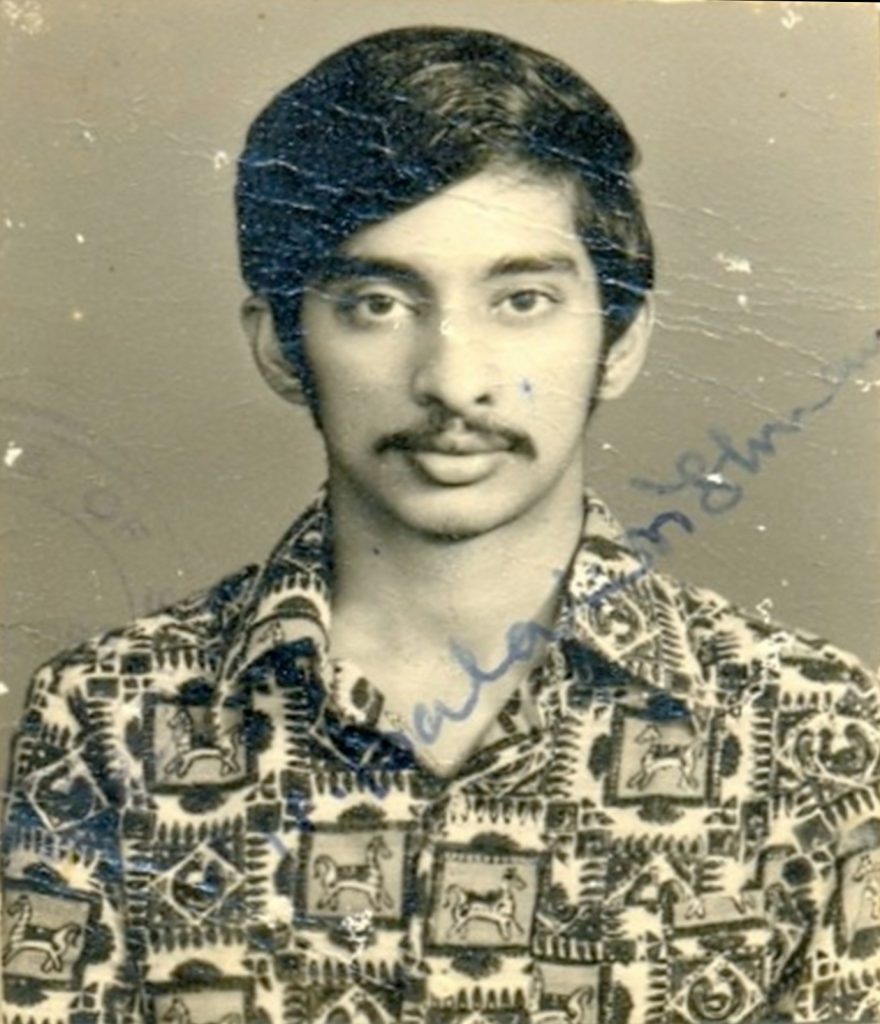

Narayanaswamy Balakrishnan (“Balki”) has spent over five decades at IISc. Upon completing his BE (Hons) from the Coimbatore Institute of Technology, he pursued his PhD from the Department of Aerospace Engineering, IISc, where he continued as a faculty member. He contributed to diverse areas, including aerospace electronics, computational electromagnetics, and information security. He also played a key role in setting up the National Centre for Science Information (NCSI) and Supercomputer Education Research Centre (SERC) at IISc and served as the Associate Director from 2005 to 2014. In this interview with CONNECT, Balki reminisces about his research, work on national programmes, and time in the Institute administration.

Can you tell us a bit about your background? How did you come to join IISc?

I was born in the small town of Villupuram, Tamil Nadu. I joined the new branch of Electronics and Communication at the Coimbatore Institute of Technology for my BE. But my brother, who was then doing his PhD at IISc, advised me that a BE was not a terminal degree.

Srinivasa Sampath, the Director of IIT Kanpur, once visited our college for a lecture on electronics. I was dropping him off at the railway station after his talk when he asked me about my future plans. I told him that I was thinking of joining either IISc or Bharat Electronics Limited. He said to me, “Don’t be mad. Join the Indian Institute of Science.” I later learned that he was an IISc alumnus and held the Institute in high esteem.

Coming from a small town, I knew little about engineering research. But I weighed all my options and decided to join IISc, while keeping an eye out for openings abroad. A few years before 1972, the Department of Aerospace Engineering at IISc started a group called Guidance and Control. I finished my BE in the year 1972 and joined IISc for an MSc (Engg). I have been here for 53 years.

How did you end up doing a PhD here?

When I joined IISc, my future supervisor, S Ramakrishna, told me that he was working on building a guidance system for a surface-to-air missile and was looking for someone to work on electronics hardware. Ramakrishna was a visionary; he was extremely generous and gave us plenty of freedom.

One evening, he visited the lab at 8.30 pm – I used to work very late – and asked me to explain what I was doing. Then, he said: “You are doing good work.” And he suggested that he will request for conversion of my registration to PhD. The whole process of conversion was a breeze.

What made you stay on as a faculty member at IISc?

One of the nice attributes of this Institute is the extreme amount of freedom that one has to do research. For my PhD, I worked on the constrained optimisation of antenna arrays. I was doing purely electronics work in the aerospace department and still being appreciated. Simultaneously, I worked on my supervisor’s project on re-engineering the guidance package for a Russian missile that India was manufacturing at that time.

After completing my PhD, I was offered a postdoctoral fellowship at Ohio State University, USA. By then, I had met my wife, who was also a PhD student at IISc. Her parents insisted that we get married before I left.

My supervisor was not happy that I was leaving. He asked the Director, Prof Satish Dhawan, to dissuade me from going. Prof Dhawan said, “Balki, if you go abroad, you will be a screwdriver. Somebody else will turn the screws. If you stay back, you can turn the screws.” Prof Dhawan requested me to stay at the Institute, which I did. I have no regrets.

What did you like most about IISc?

As a student, it was the mess, the hostel, the computer centre, the Gymkhana, and its night coffee. The Gymkhana cafe was open only till 1 am, but I usually worked until 1.30-2 am. So, we would go to the Yeshwantpur railway station to have hot coffee or tea and return, by which time our computer program run would have completed.

After I became a faculty member, my students became part of my family, and many are still in touch with me.

Thirdly, my work on national projects, which became the driving force of my life.

What projects did you work on for the defence sector?

Tons of them! At that time, the entire aerospace department was working on defence projects. There was a saying that not a single object would have gone up in the air without a nut or bolt designed by the department.

When my supervisor left IISc, I was asked to work on the second phase of his missile project, on the guidance, coding scheme, and control. Dhawan also asked me to work for ISRO on the theoretical analysis of antennas mounted on satellites.

I also got involved with India’s AWACS [airborne early warning and control system] programme. The first challenge was power generation using travelling wave tubes, the second was designing low side lobe arrays, and the third was clutter analysis to distinguish an enemy aircraft from the sea, forest, and so on. This was my foray into large defence projects. We also worked on sensor fusion, and on Radar Cross Section (RCS) analysis of one of the Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA)’s new aircraft.

Once, I went on a sabbatical to the National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL), USA. It was a turning point in my life. We used electromagnetic analysis to separate individual radar echoes from hail, snow, and rain collected using their NEXRAD weather radar. When I came back to India, I told my defence contacts that this approach can also be applied to detect stealth aircraft.

A Russian scientist once made a passing remark that if the aircraft is completely stealth, it does not reflect the radar signal, but you could track its wake. One of my students worked on it and published a study on detecting low-visibility aircraft from its wake pattern.

How did you become involved with the Supercomputer Education and Research Centre (SERC)?

I was already doing a lot of programming in the aerospace department. During IISc’s platinum jubilee celebrations in 1979, the Director, S Ramaseshan, sent several proposals to the government seeking funding for emerging centres. He also said that we should ask the Prime Minister for a single, large entity. The Institute decided to ask for a supercomputer.

The person put in charge was Roddam Narasimha. As his former student, I was pulled in as the “ball picker boy” in the team – tasked with finding out what systems were available across the world.

We proposed a computing system called the CRAY Y-MP. It had an onion-layered configuration, with 90% of the users on peripheral smaller computers while the rest had deeper access. The proposal was sent to the government. Prof V Rajaraman [from IIT Kanpur] was invited to head the new centre [SERC].

Due to an enormous delay in getting the CRAY supercomputer, we submitted a revised proposal to the government.

Luckily, at that time, single monolithic supercomputers were being replaced by distributed systems with powerful processors. We decided to purchase a distributed system, and Prof CNR Rao helped us get cabinet clearance. We had an IBM machine for computation, another machine for graphics, and one for databases – all connected through a powerful network so that they shared resources. It was a unique concept.

For both the target identification and information security research, we needed a tremendous amount of computational power. If I hadn’t moved to SERC, it wouldn’t have been possible.

Can you talk about your work on information security?

By the time Abdul Kalam became the Scientific Advisor to the Defence Minister, I was working continuously with him. I was his “1 am friend” – he frequently called me at that time. I had also been visiting Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) every summer and learning a lot about information security. I worked on the Million Books to the Web project. My mentor at CMU, Raj Reddy, said to me: “Balki, the whole world is working on information security. You must convince the Indian government to look into it.” I came back and informed Kalam. He agreed, and that’s how the country’s information security research programme started.

After 2000, my entire life revolved around information security. I was involved with CERT-in [a national nodal agency for responding to computer security incidents]. We trained 120 people from DRDO and the government sector. Monitoring and traffic control of the internet was another big problem. For this work, my students got the AGNI award, and I got the DRDO Academy Excellence Award. Subsequently, most of our work was on intrusion detection systems and improving the accuracy of intrusion detection.

What was it like working with government and strategic organisations?

I realised that the way to succeed with government projects is not to say, “You lay off your hands and give me the money, I will do the work,” but to involve them closely.

For example, India has been importing a lot of equipment from China and non-friendly countries. How do we know that they are secure? The Department of Telecommunications (DoT) put six of their senior engineers here on campus, and I worked closely with them, guiding them on developing standard procedures for testing the equipment.

As a member of the National Security Advisory Board, I got a bigger picture of national security. The people I worked with in DRDO were very understanding, particularly Kalam, VS Arunachalam, and VK Aatre – they were all of the opinion that university research cannot be constrained.

The important thing is that these organisations have to share data with us. When telecom companies had to share call records, they were anonymised before sharing.

For my work at SERC and on information security, I received several awards, including the Padma Shri. I don’t think I would have gotten these awards if I hadn’t worked on national programmes.

Can you talk about your role in the National Supercomputing Mission (NSM)?

In 2010, K Kasturirangan, who was a member of the Planning Commission, asked me to work on a proposal for establishing supercomputing facilities in India. There were two issues: getting access to supercomputers and making them. We decided to focus on access.

We gathered people from across the country to write status papers across fields – bioinformatics, drug design, aerodynamics, and more – outlining national needs. The NSM proposal was approved, with IISc and the Centre for Design of Advanced Computing (C-DAC) as implementing agencies. A Technical Advisory Committee was formed, and I became a member. VK Saraswat, another IISc alumnus, was the head. He felt that we should do more within India. We have finished phase I. Phase II is now ongoing.

Do you think more scientists should contribute to national projects?

Absolutely. Where else will [organisations like] DRDO go? But that does not mean everyone should. IISc, for example, evaluates faculty members on five pillars: teaching, research, students, consultancy, and technology development. There are people who want to do science – we can’t ask them what product they have developed. You can’t ask a person who develops products how many publications they have. Some are original thinkers, and some are excellent teachers. Everyone should have the freedom to choose between the five pillars, but they must contribute substantially enough in that area.

How did you get involved in administration? You were the Associate Director when P Balaram was the Director.

I’d been in the Institute administration since the age of 32. I was the convenor of the National Centre for Science Information (NCSI), the Centre for Microprocessor Applications, and Associate Chair of the Centre for Scientific and Industrial Consultancy (CSIC). I was brought in to head SERC and later the Division of Interdisciplinary Science.

When I became the Associate Director, I got the additional responsibility of bringing in money to the Institute, while Balaram handled faculty and students. When Balaram was trying to start the undergraduate programme, several people opposed it, including me. I told him: “Don’t start this programme. But God forbid you start this, please appoint a Dean of Undergraduate Affairs.” I had handled student affairs for 10 years as an advisor to two directors. PhD students were already mature. Bringing 16-18 year-olds on campus – I didn’t know whether we had the experience. I opposed it only for this reason.

Balaram listened to me, and in the Senate, he said: “The first person who opposed this programme is Balki, my Associate Director. He said that if I am going ahead with this, I should appoint a UG Dean. I never disagree with Balki, so I am appointing one.” The programme, of course, turned out to be tremendously successful.

What do you like most about the campus?

I love everything about this campus.

The jubilee garden used to be an undeveloped area with a pond; you would find snakes, fish, and numerous birds. I lived in DQ19, in the faculty quarters on campus. My children would listen to the chirping of birds early in the morning and try to identify them.

At one point, the number of birds on the road leading from the old biochemistry building to the library was so high that you couldn’t walk by without getting hit by bird poop.

When I was a student, in the mess, if I took one poori less, the server would ask me: “Did your guide scold you? Please eat more.” I feel that personal touch is gone now.

What advice do you have for students and young researchers?

Be the best in whatever you are doing. Don’t plan too much. Life will be nice to you.