How did life emerge on Earth? (Spoiler alert: We still don’t know)

On a cold winter evening in 1952, in a dimly lit lab at the University of Chicago, Stanley Miller, a 22-year-old graduate student, stared at the murky brown sludge in the shake flask in front of him, his stomach sinking. Days of meticulous work had led to this unappealing, tar-like mess. He fretted over how to explain his failure to his graduate adviser, Harold Urey.

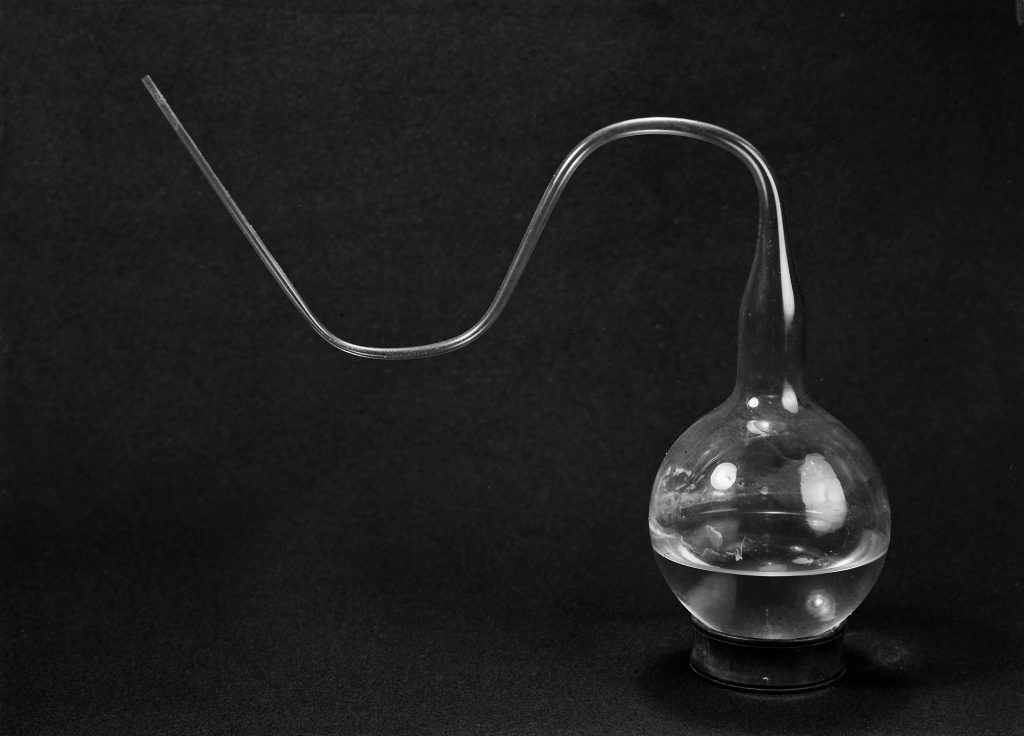

It had been a brash experiment. Miller thought that mixing a bunch of inorganic gases in a specially designed glass apparatus and passing electricity through them would create organic molecules. But the murky mess did not look anything close to what he had expected.

Common sense told him to start over, to scrub the flask clean, and abandon the experiment altogether. But something – curiosity, desperation, or perhaps sheer stubbornness – held him back. Miller reached for a beaker of water, dissolved the brown tar, and prepared to run it through a paper chromatography column. It was a last-ditch effort, more from habit than hope.

As the chromatogram developed, Miller leaned in closer. Then he froze. His breath caught in his throat. What he saw defied expectations – something no one had ever glimpsed before in a lab. The chromatogram clearly showed the presence of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins.

Perhaps he did not know it at the time, but Miller stood at a precipice where centuries of curiosity about the origin of life had converged. For a long time, humanity has been grappling with the profound question of how life emerged from lifelessness. Scientists have strived to find out how complex molecules like proteins and DNA first emerged and coalesced to create lifeforms. Fast forward to 2025, and we still don’t have a clear answer. People from various fields like biology, chemistry, astronomy and even philosophy have approached the question of the origin of life from different angles. Pulling at this thread has also led us to question what constitutes “life”, and if life is possible elsewhere in the universe.

For a long time, humanity has been grappling with the profound question of how life emerged from lifelessness

“This historical question, in my opinion, is not something that can ever be settled,” says Shashi Thutupalli, Associate Professor at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS).

One obvious reason is that it happened way, way back in time and none of us was around to see it. We can only guess what the Earth would have looked like four billion years ago – which is when many scientists think life might have emerged – but we can’t faithfully replicate those conditions in a lab with complete confidence.

This hasn’t stopped scientists from trying. Today, a lot of them work with precursors of biomolecules and even primitive cells to understand prebiotic chemistry, how molecules may have interacted to form reaction networks, and how the first ordered structures may have emerged.

“We can only improve the confidence in our guesses as we collect more and more information and evidence,” Shashi adds.

The chicken and the egg

For a long time, scientists seeking to pinpoint the origin of life focused on figuring out which biomolecule emerged first. We now know that the cell is the fundamental unit of life, and everything happening in that tiny compartment is under marching orders from the nucleus. But the real boss is the DNA inside the nucleus – the genetic material that holds the instructions to make proteins, which do all the work in the cell. DNA is copied into mRNA or messenger RNA, which is then “translated” into a protein by ribosomes – and this process is known to happen only in this order.

Molecular biologists call this the “central dogma” of life, but it raises an important question. Proteins, in the form of enzymes, are needed to make and copy DNA, but how can a cell make proteins if DNA is not made first? This is a confounding chicken-and-egg problem, with no definitive way to say which came first: DNA or protein.

Proteins, in the form of enzymes, are needed to make and copy DNA, but how can a cell make proteins if DNA is not made first?

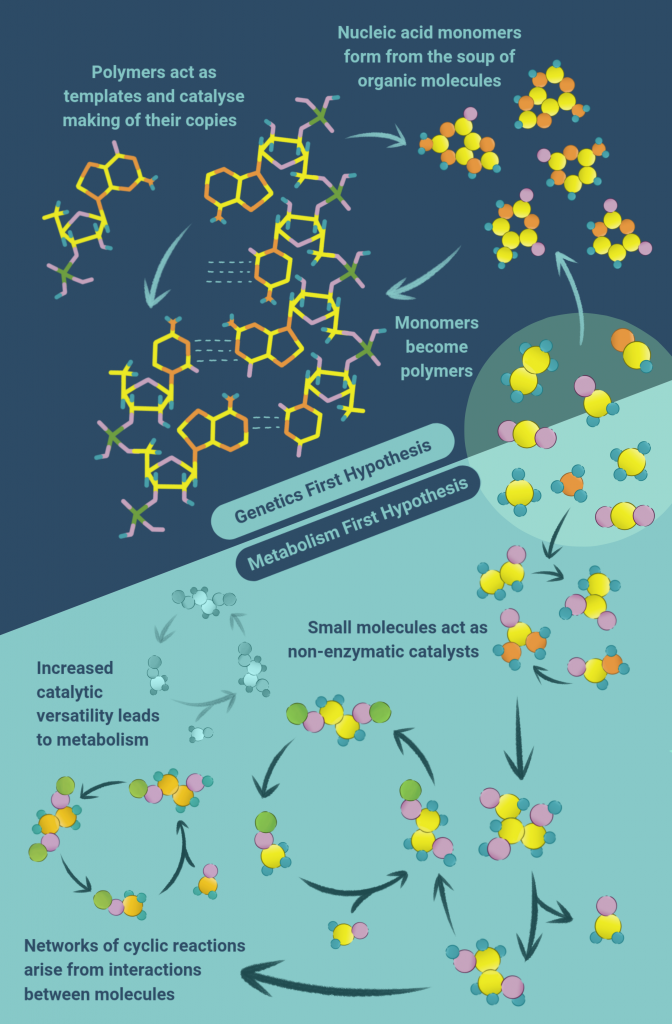

Scientists caught a break in the 1980s when Thomas Cech and Sidney Altman at Yale University showed that a third entity called RNA could catalyse reactions, just like enzymes. RNA differs from DNA in that it has ribose sugar (instead of deoxyribose), which has an extra oxygen atom. Although this makes RNA quite unstable, it also gives it the ability to act like an enzyme. This means that on early Earth, RNA likely both acted as a carrier of genetic information and catalysed protein production. This is often regarded as the ‘RNA World’ or the ‘Genetics First’ point of view.

That’s what the molecular biologists say, but others – physicists, geologists, astronomers and even information theorists – don’t really buy into it. RNA is a fairly complicated polymer made up of small repeating units called nucleotides, which have a complicated structure themselves.

“The question always is [then] where does something like RNA itself come from?” posits Shashi. “It’s a little bit like kicking the can down the road.”

Without explaining where RNA came from, the ‘Genetics First’ theory seems like making castles in the air. It’s hard to believe that RNA was able to polymerise without an amenable chemical environment, since the bonds between RNA nucleotides are fragile and get easily broken by water. By the time RNA emerged, ‘life’ was probably already quite complex and was sustained by networks of chemical reactions.

“The creation of life on Earth must have started with small molecules and simple chemical reactions interacting to form networks,” says Subinoy Rana, Associate Professor at the Materials Research Centre (MRC), IISc. “About 4.7 billion years ago, the temperature and resources available may not have been favourable for the generation of genetic material first.”

This other possibility is called the ‘Metabolism First’ theory. We live, breathe, eat and reproduce thanks to a series of chemical reactions which break down complex molecules and synthesise new ones. All of these chemical reactions together constitute our metabolism.

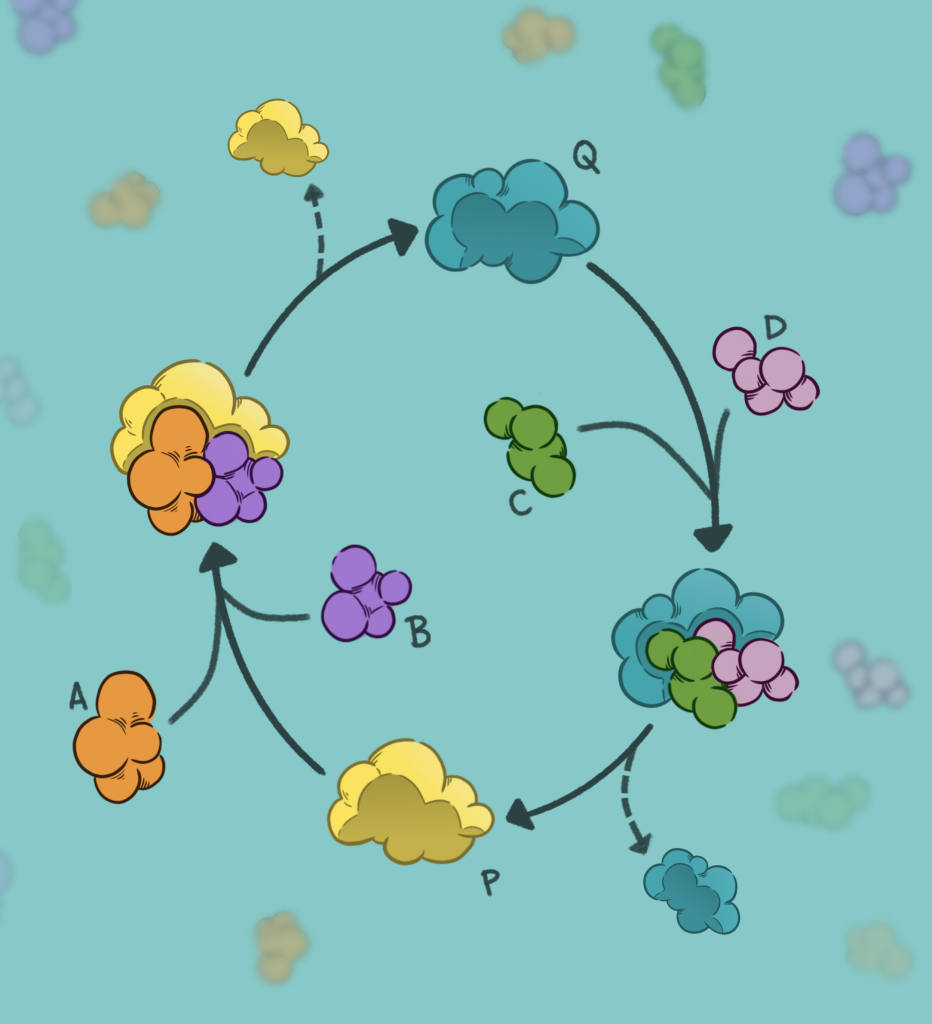

So then life probably began not with DNA, RNA or proteins, but with simple chemical reactions catalysed by networks of small molecules or rocks rich in iron sulphide minerals in hydrothermal vents deep under the sea. Imagine that there was a cycle of reactions, the product of one acting as the starting material for the next, ultimately looping back to the molecule it began from. This is a nice, closed, chemical system acting somewhat like a copying machine. Something like this could have rapidly given rise to a large number of molecules.

A lot of chemistry happening in the cell today is probably a vestige of these primitive reactions. The Krebs Cycle, for instance, is the reaction at the heart of breaking down glucose to fuel the cell, and many offshoots of this reaction are important in building proteins and other complex molecules. Some scientists think that a reverse version of the Krebs Cycle may have kickstarted life, with simple materials like carbon dioxide and hydrogen gas creating complex biomolecules, without the need for any enzymes.

Naturally, molecular biologists aren’t very happy with this theory. They find it hard to digest that metabolism could have just suddenly materialised without DNA and RNA, which currently regulate a lot of the cell’s chemical reactions. And of course, this still doesn’t explain how RNA came into existence.

A possible solution lies in what scientists suggest may have been an ‘autocatalytic set’ – a collection of mutually catalysing chemical reactions. The product of one reaction catalyses a second reaction, creating a molecule which can, in turn, catalyse the first reaction. This is a self-sustaining system and offers the possibility of rapidly generating more complex molecules, polymerising and even stabilising the first RNAs which could then control the chemical reactions – unifying the ‘Genetics First’ and ‘Metabolism First’ theories.

Which theory a scientist supports seems to depend on the way they approach the problem. “Given that I come from the physics way of thinking, where processes of self-organisation and pattern formation readily happen in physicochemical systems, I believe that there are things which look like metabolism even before those patterns start to get encoded in some material,” says Shashi. “But who knows what really happened, right?”

A warm little pond

It’s hard to say what the Earth would have looked like four billion years ago, but scientists have made reasonable guesses. For starters, it would have been incredibly hot and there would have been no oxygen (because photosynthesis had not yet begun). The atmosphere was likely teeming with other gases like ammonia, methane, hydrogen, and water vapour. How did life emerge under these toxic conditions?

It was a question that intrigued naturalist Charles Darwin shortly after he published his famous book on the origin and evolution of species. Unsurprisingly, he was among the first to ponder on the question – something he had not explicitly addressed in his book. Darwin felt that at that point, science was not advanced enough to shed any light on how the first ‘cell’ came about. In a letter to his friend Joseph Dalton Hooker, a famous botanist, he said, “…it is mere rubbish thinking, at present, of origin of life; one might as well think of origin of matter.”

But something probably changed a few years later because he wrote another letter to Hooker in 1871. “This is when I think modern views began to crystallise,” explains Padmanabhan Balaram, former Director of IISc. “[Darwin] imagined that maybe life originated in a warm little pond which was filled with all kinds of chemicals. He realised that many elements were needed for making living organisms.”

Our understanding today is that Darwin’s warm little pond was more like a hot, boiling soup which eventually provided just the right conditions for life to evolve. But several pieces of the puzzle are still missing – life can’t just come out of nowhere, since only living organisms can give rise to living organisms. The first ‘living organism’ – likely a single cell – was probably the result of a bunch of organic molecules coming together.

Something out of nothing

Humans have been quite creative in coming up with explanations for the origin of life. Some believed that life hitched a ride on comets and asteroids in the form of spores which germinated once they hit the Earth. Others, like naturalist Georges Cuvier, were adamant that life kept getting wiped out and rebooted, courtesy of divine intervention or cosmic disasters – something he called the theory of “catastrophism.”

The weirdest of all – and shockingly widely accepted – was the theory of “spontaneous generation,” that life could just magically poof into existence. People observed that wounds of injured soldiers, when left untreated, got badly infected and even infested by maggots seemingly out of nowhere. There were all sorts of “recipes for life” – mice emerging from dirty laundry, flies from rotting meat and even frogs from mud – all resulting from overenthusiastic scientists drawing rash conclusions from innocuous observations.

This was the subject of an intense back-and-forth between scientists until French chemist Louis Pasteur came along. He boiled a nutrient broth in special flasks with long, curved necks that let air in but not dust and microbes – and no life appeared. He proved that rotting food wasn’t conjuring up new life, it was just bad at keeping life forms like bacteria out. Once and for all, spontaneous generation was relegated to the great trash heap of bad scientific ideas.

In the 1920s, Alexander Oparin and JBS Haldane popped into the scene with the idea of chemical evolution or abiogenesis – that life on Earth originated from simple inorganic molecules which reacted to form more complex organic molecules, somewhere in the boiling primordial soup. These could be either amino acids (the building blocks of proteins) or nucleotides (the building blocks of DNA and RNA), which eventually would have somehow polymerised to RNA and proteins.

This sounded sketchy and unlikely until Miller decided to take a bunch of inorganic gases in his huge glass apparatus and pass an electric discharge through it, attempting to simulate the extreme conditions on primordial Earth. It was good fortune that Miller decided to analyse the brown sludge instead of throwing it out. What he found were the amino acids alanine, glycine and aspartic acid – some of the building blocks of proteins – proving Oparin and Haldane’s hypothesis once and for all.

What is life?

Miller’s discovery and subsequent publication in Science in May 1953 was a huge breakthrough – it made the front pages of both The New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune, which are credited with popularising the phrase “the origin of life.”

When most of us think about life, we think about our existence as living, breathing humans. But the origin of life isn’t about the origin of human beings – that’s what Darwin talked about in his book – it’s about the origin of the cell. By looking at shared genetic material between organisms, researchers have traced our genealogy all the way back to a hypothetical organism they call LUCA – the Last Universal Common Ancestor, the original progenitor cell from which all life today likely emerged.

The ‘origin of life’ isn’t about the origin of human beings, it is about the origin of the cell

“LUCA is where biological evolution starts, and it already had all the biochemistry that is needed – but where did LUCA come from?” wonders Balaram. Understanding the origin of life – specifically, LUCA – appears to be a twofold problem. “A cell is a complex mixture of chemicals. A lot of chemistry or biochemistry put together gives us these magical cells, which seem to work wonders afterwards. Where did all these chemicals come from? That’s chemical evolution, what Oparin and Haldane spoke of. Then you have this organisational problem of how you put all of that together. This is now the empty space of evolution.”

To understand how simple organic molecules floating around in a primordial soup crossed the threshold from chemistry to biology, we first have to define what we mean by life.

Some scientists have taken a stab at this. In the mid-1940s, physicist Erwin Schrodinger delivered a series of lectures titled “What is Life?” which were later condensed into a book. Living systems, he suggested, should have the capability to reproduce and the “offspring” should have characteristics of the parents – genetic inheritance.

But it is not that simple. It’s easy to come up with a laundry list of attributes – growth, metabolism, reproduction, evolution and so on – and say that a living thing should show all of them. There are always exceptions to every attribute that we can put down. For example, we intuitively think that an autocatalytic reaction network of molecules is not ‘living,’ but it turns out that it has most of the attributes listed above. So is it living or non-living?

However, there are some attributes that scientists now largely agree could lie at the heart of defining what life is. One of these is compartmentalization.

In a 2001 Nature paper boldly titled “Synthesizing Life”, Jack Szostak, David Bartel and Pier Luigi Luisi at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) suggested that early Earth probably had crevices or pores in rocks where molecules and reactions were cordoned off into compartments formed by the assembly of lipid molecules, or in aqueous droplets called coacervates. They added that this vesicle formation likely occurred between layers of clay minerals, which not only helped protect the molecules and reactions but also catalyse the latter. This, they successfully argued, was crucial for creating the first living system.

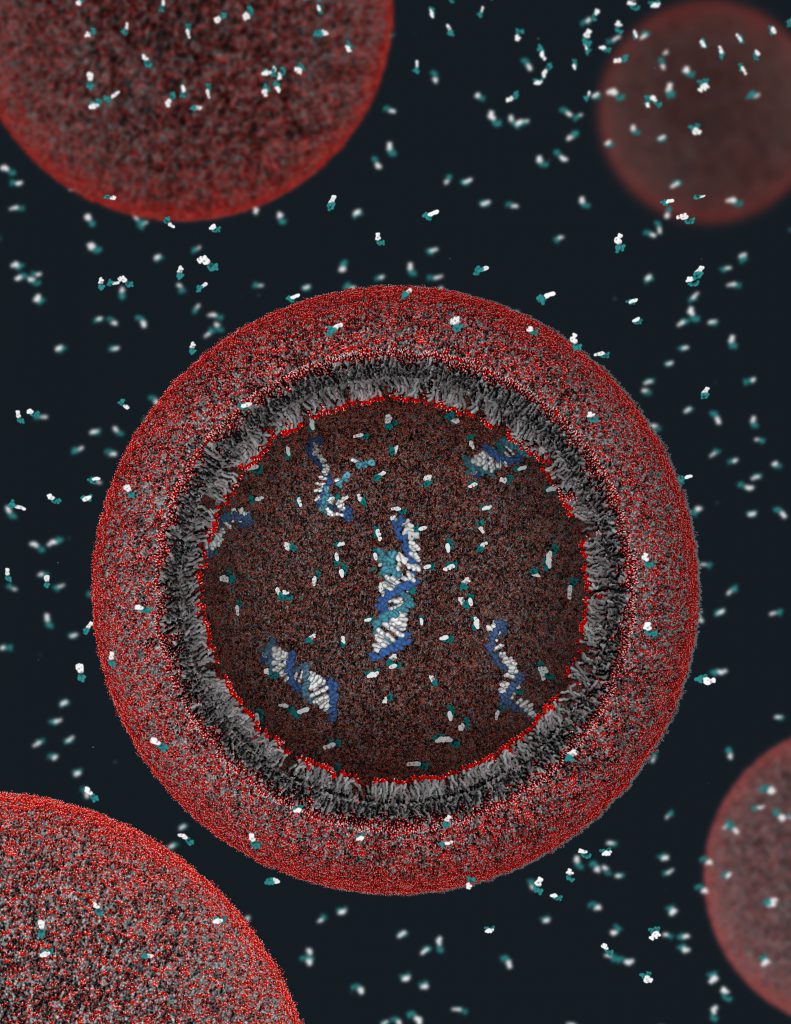

Encapsulating life

The cell membrane – an elegant bilayer of lipids with a water-loving head and a water-repelling tail – is a good starting point to think about what primitive compartments were like. In water, these lipids self-assemble into membranous structures called vesicles, sheltering a cavity where primitive reactions could have occurred. When they grow too big, vesicles can bud off and split into two – similar to how a cell divides. But vesicles aren’t stable in the presence of ions like magnesium, which are critical for catalysing many biochemical reactions.

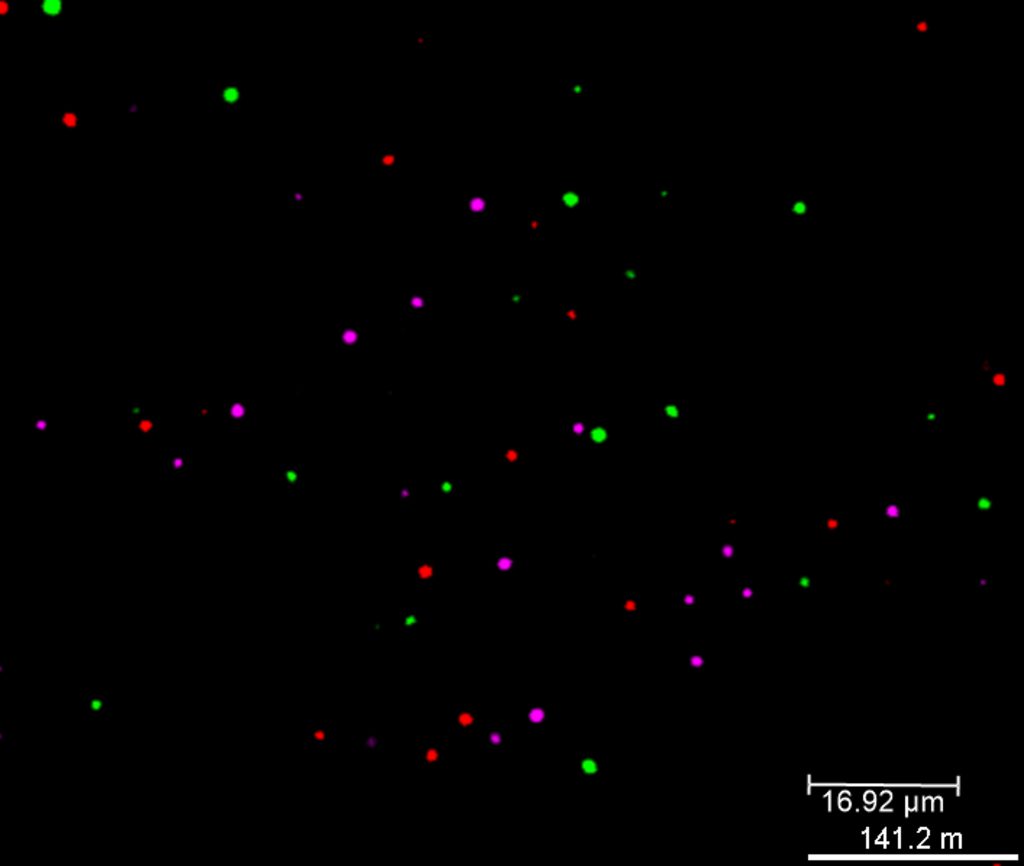

Enter coacervates. Similar to modern cell organelles, these are dense clusters formed by chemical interactions via a process called liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS). This is similar to what happens when you put oil in water – you can see them as two separate, unmixed phases. Unlike vesicles, coacervates lack membranes but can still encapsulate biomolecules and reactions, making them intriguing candidates for primitive compartments.

Shashi’s lab has recently shown that autocatalytic RNA reactions can take place inside coacervates. Subinoy’s team is similarly engineering protocells and prototissues using vesicles and coacervates. Beyond origin-of-life research, these structures are also finding applications in catalysis, sensing, bio-imaging, and drug delivery. Coacervates prove that compartmentalisation isn’t just a relic of the past – it’s a tool for innovation.

Why is compartmentalisation such a necessary feature of life? Even the most primitive cells have at least one boundary – the cell membrane – separating them from the environment. More modern cells have many small compartments called organelles inside which different sets of molecules form and react. The advantage of this separation is that they don’t interfere with each other.

“We have observed that compartmentalised structures give rise to much higher rates of reactions – something called a proximity-enabled reaction,” explains Subinoy. Reactions happen when molecules are close together and prone to colliding with each other. “Increased local concentrations in small compartments make many reactions that aren’t feasible in the lab feasible in a cell, without the need for a complicated new enzyme.” Scientists like Subinoy are exploring such self-assembled compartments to create artificial enzymes that we can use today.

Over the years, scientists have also turned to emergent properties as another important attribute of life. This revolves around a fundamental idea that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” something theoretical physicist Phil Anderson emphasised in 1972 in a Science article called More is Different. This is a common paradigm in biology anyway – cells come together to form tissues which have properties individual cells don’t. Origin-of-life researchers expect that molecules which came together to form the first cell also demonstrated emergence. Emergent traits are not something you have designed into the individual molecule itself. They are unexpected properties that emerge from the interactions between molecules floating around in the soup.

Shashi reinforces this idea with an example. “I can build a robot which exhibits the properties of life. Imagine that I program it to get into a factory and make a copy of itself – I wouldn’t call that living, because I had to tell it what to do,” he says. “If the robot were to do this of its own volition, that’s an emergent property, and that’s one step closer to being called ‘life.’”

Mysteries remain

On a bright December morning in 2024, Juan Manuel García-Ruiz, a geologist at the University of Granada in Spain, was in his lab staring at a simmering mixture of gases. The setup was familiar to Stanley Miller’s from over 70 years ago – a huge glass apparatus with two electrodes jolting the gases with artificial lightning. But García-Ruiz was not just trying to replicate the experiment – he was searching for something Miller might not have seen.

When he and his team peered into the vessel after the reaction was done, García-Ruiz probably expected the complex soup of organic molecules that formed. They isolated more amino acids than Miller had originally created, and even the five nucleotide bases found in DNA and RNA. But he also had a pleasant shock: tiny microscopic bubble-like compartments – protocells – had formed inside the flask.

The team was stupefied because not only were building blocks present, they were spontaneously assembling into structures that resembled primitive cell membranes. The main thing García-Ruiz had changed from Miller’s experiment was adding silica – something that would have been found in the clay pockets of early Earth. This simple change had triggered the switch from chemistry to biology.

This new experiment challenged several accepted ideas about the origin of life. We used to think that the first protocells would not have been assembled until around 3.8 billion years ago, when environmental conditions became just right. But García-Ruiz’s experiment indicated that this form of ‘life’ could have emerged as early as 4.6 billion years ago, during the Hadean era. Was the boiling soup of 4 billion years ago then not the right environment? It’s the most recent example of how our understanding of the origin of life changes every single day, with every new experiment.

“Science is something in which you ask a question and try to find an answer by experimentation – and your explanations may change over time,” says Balaram. “What somebody knew and understood about the origin of life 300 years ago may seem incredulous today, but it was wonderful at that time.”

Who knows where we will be in 300 years?

Life beyond Earth

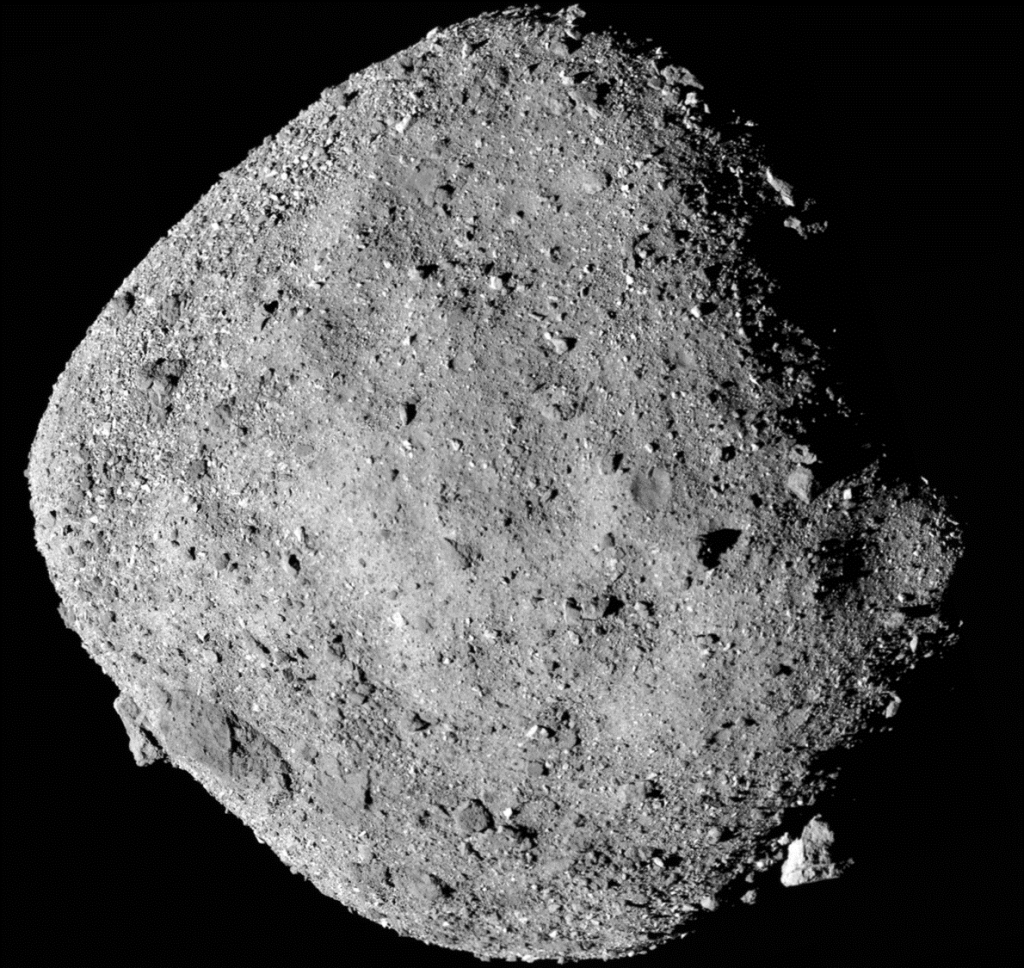

Was the origin of life unique to Earth, or could it have happened elsewhere? NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission recently returned with samples from the asteroid Bennu, revealing a treasure trove of biomolecules. Scientists isolated all five nucleotides found in DNA and RNA, 14 different amino acids, and a lot of ammonia and formaldehyde, which are key ingredients for complex chemistry. This confirms that the building blocks of life can form in space, reinforcing the idea that life’s origins may not be limited to our planet.

This isn’t the first time that space has shaped our understanding of life’s beginnings. Decades after Miller’s famous experiment, meteorites were found to contain amino acids and other organic compounds, proving that similar processes occurred in space. The Murchison meteorite, which fell in Australia in 1969, carried lipids that, as American biologist David Deamer demonstrated, could form vesicles in water. This suggested that early Earth could have had the right conditions for compartmentalised structures.

These discoveries raise an even bigger question: If life’s building blocks are so widespread, could life itself be common across the universe? Astrobiologists are searching for the answer by identifying planetary environments that might support life, and by using biosignatures to detect traces of life. From the subsurface oceans of moons like Europa and Enceladus to ancient Martian riverbeds, the search for life is expanding beyond the Earth. If Bennu carried the same molecules that seeded life on the Earth, then perhaps life isn’t a rare accident – it’s an inevitability written into the chemistry of the universe.

Parth Kumar is a second year BSc (Research) student at IISc and a former science writing intern at the Office of Communications

(Edited by Ranjini Raghunath)