CONNECT spent a day with Savitha P who ensures the smooth functioning of the nanofabrication facility

It is an office that speaks to the work that Savitha P handles at the Centre for Nano Science and Engineering (CeNSE) at IISc.

The office itself is simple – populated by a desk, a computer, a couple of chairs, a fashionable hourglass, a smattering of awards, and a few potted plants. A cupboard sits on one side, groaning with files and boxes of documents that betray signs of constant rummaging. There are keys hung neatly on the wall, meticulously marked and accounted for. If the National Nanofabrication Centre (NNfC) is the heart of CeNSE, then this room is its aorta.

Amidst the chaos, Savitha’s desk is clean and organised, an appropriate metaphor for how she carries out her work as the Chief Operating Officer (COO) of the NNfC, part of the larger, living, breathing, complicated organism that is CeNSE.

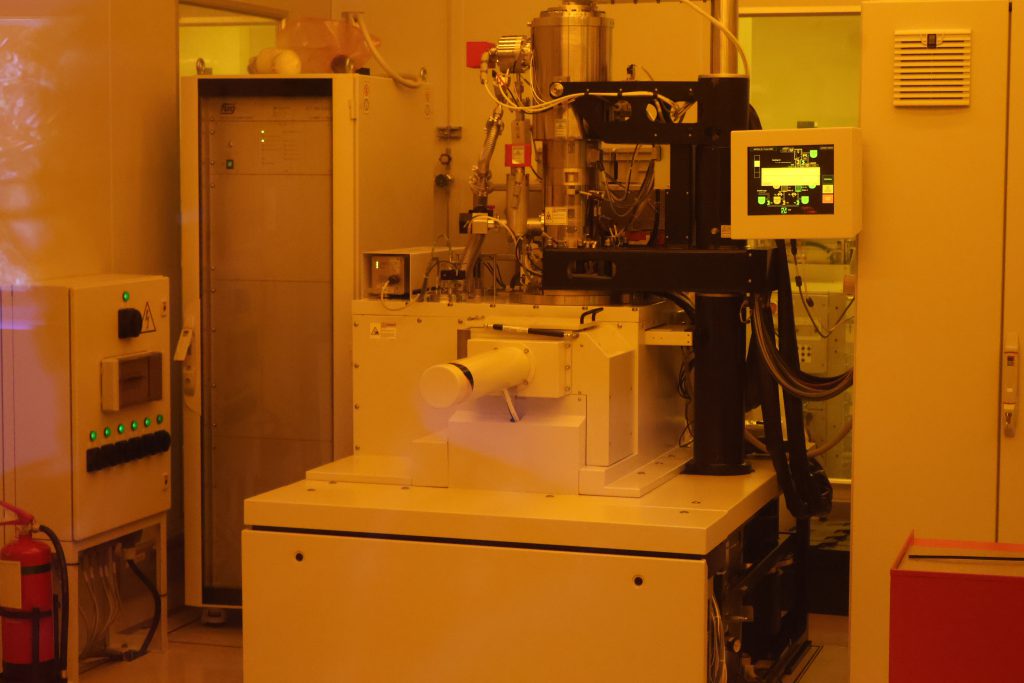

Savitha’s day starts bright and early. She is in her office by 9 am. On this day, she is a tad anxious. The NNfC, put together at enormous expense and with great precision and care, is getting a new tool – an electron beam lithography system called the EBPG 5150+. The new acquisition will form part of the 14,000 sq ft facility where one can experiment in various labs – such as the Lithography lab, etch and deposition – with work ranging from semiconductors-dielectrics to developing and fabricating everything from advanced sensors to sophisticated GaN transistors. The latter have promising applications in power electronic applications due to their higher breakdown voltage and power efficiency compared to traditional silicon-based transistors. The facility, bustling with activity, is used by researchers, students, entrepreneurs, and innovators from outside IISc as well. Since it was established in 2012, it has also given birth to several private companies that are working on cutting-edge areas of medicine, clean energy, and more.

The nerve centre of the facility is the clean room – a room free of dust and other contaminants – which is now shut for yearly maintenance, making it the ideal time to introduce the new tool. Savitha’s mind runs through a laundry list of all the things that could go wrong – from potential damage to the new piece of equipment to dust and vibrational effects (the facility is constructed in a manner as to isolate or dampen vibrations that could affect the performance of the tools in the facility).

At 10 am, she rushes for a routine meeting with her colleagues to discuss the day-to-day running of the facility, one that lasts for the better part of an hour. As she bustles into the office again, there are two people and a crisis waiting. There has been a mix-up with a new software. Someone, it would seem, had tampered with the system and password. It takes a few minutes, but Savitha successfully manages to stop the crisis from escalating.

As she sits down at her desk, there is already a booking request waiting for the clean room. “The clean room is booked months in advance,” she says matter-of-factly, about the demand for slots at the state-of-the-art facility, with people travelling from all over the country to use it.

“If something goes wrong, things get backed up. That has a huge effect on people who are travelling down and all such,” she says. As Savitha goes through her email, she elaborates on her responsibility.

“I have to make sure things work well for our users,” she explains. “It is on the operations team. You sit with various teams to understand what is happening and what is needed. You have to be on top of things constantly.”

Besides having to ensure the smooth running of the facility, Savitha is also in charge of procurement. From tools to chemicals (the facility needs a high level of purity in the chemicals they use), most of it comes from abroad. Should anything go wrong, Savitha and her team have to figure out a solution themselves as the waiting period to get in touch with the companies that make and distribute them is often too long. To that end, CeNSE has an active programme in place to try and help build the local ecosystem for such products.

‘A big part of my day goes in ensuring that things don’t go wrong and if they do, that we deal with it’

“A big part of my day goes in ensuring that things don’t go wrong and if they do, that we deal with it,” she says. Every decision she makes has a significant impact – whether it has to do with the functioning of the facility or its future. She recalls one such instance. When she was at a Fair Price shop one day, she got a call about procuring a new tool. The cost was around Rs 5 crore. Savitha cleared it saying that it can be budgeted. The ration shop owner was left wondering aloud what this lady, who speaks with nonchalance about spending crores, was doing there.

As one would expect, Savitha and her team have drawn up protocols that need to be followed for everyone using the facility, as much for their safety as for that of the facility. A penalty point system has been put in place with suspensions and even permanent bans for breach of protocols.

At 12.15 pm, Savitha heads up a few floors in the CeNSE building for another meeting. This one, she says, is to work towards developing the nanotechnology ecosystem in the country. An important part of this agenda is to ensure the success of the central government’s India Semiconductor Mission. One of the biggest challenges in the field is building precision equipment without always having to import them. Towards this end, CeNSE is working with a company to help improve the quality of one specific tool. There are six people in the room engaged in serious discussion about the instrument in question. Suggestions to rebuild certain parts are debated and explained. Flow charts and diagrams are projected onto the wall. Savitha makes copious notes and gives her feedback. At the end, the minutes of the meeting need to be transcribed. It takes an hour and Savitha heads down to have lunch.

‘I love cooking. Every chemist is a cook. It is the same process, mix and heat it … optimise and experiment’

Lunch is a comfortable ritual, with Savitha and her colleagues sharing their meals with each other. “I love cooking,” she exclaims. “Every chemist is a cook. It is the same process, mix and heat it … optimise and experiment.”

A chemist is who she is. Hailing from Thrissur district in Kerala, Savitha completed her Bachelor’s degree in Chemistry from Calicut University in 1996. She then did her Master’s at the University of Pune (now Savitribai Phule Pune University) with the intention of eventually doing her PhD. But the culture shock of moving to a different city was a punch in the gut for someone who grew up in a safe environment. Having to converse in a new language, be it Marathi, Hindi or even English, was a struggle for her. Her resolve to finish her degree, let alone earn a doctorate, was tested. At one point, she even called her father, telling him that she wanted to come back home. Her father, rather shrewdly, had obtained a seat for his daughter in St Joseph’s College back home as a backup. He was sympathetic to his daughter’s feelings but said something that made a significant impact on Savitha.

“I thought you were not one to give up. This was your dream,” he told her. Savitha remembers the words even to this day. She thought about it that night and next morning, called home to inform them that she was not coming back.

“If my father had said come back, it would have been very different,” she says. After her Master’s, she got into IISc for a PhD programme at the Department of Inorganic and Physical Chemistry in the early 2000s. Savitha has been at IISc since.

Following her PhD, she worked as Technical Team Lead at Cookson India Research Centre, which was housed in the Society for Innovation and Development (now the Foundation for Science, Innovation and Development) in IISc. After five years of working here, she moved to NNfC as a technology manager in 2010.

“That move was a big change for me,” she admits. As a technology manager, she had to manage a high temperature chemistry facility. She learnt on the job and in a few years, she was rewarded. She was promoted to the position of COO in 2017.

‘CeNSE is looking forward to the future. There are companies coming out of CeNSe that will make a big impact on people’s lives’

Soon after lunch, Savitha marches into the NNfC to check on the new tool, the EBPG 5150+, which was arriving. A heavy table, which will hold the tool, needs to be bolted to the floor because the tool is sensitive to external vibrations. She watches anxiously as the installers lower the table. It had to go well. No, it had to go precisely. Or it will mean a further delay in reopening the cleanroom, which Savitha can ill afford. But before the installation is complete, at 3 pm, she rushes out for another meeting. The meeting is with a team that is making a video to explain the work that goes on in NNfC. The scripting process is ongoing. As soon as the meeting is over, she hurries back in to check on the installation. It had gone well. She breathes a sigh of relief.

There are two more meetings before Savitha can call it a day. One is a debrief, the other is with the head of the facility. Her work hours are long but flexible, she admits. She is always on call. The NNfC functions throughout the day. So, if anything goes south at any hour of the day, she is the one who must decide on what action needs to be taken. It can be stressful, but she doesn’t mind. “CeNSE is looking forward to the future. It is an interdisciplinary space,” Savitha explains. She is aware that she is in charge of a facility that is shaping the future. “There are companies coming out of CeNSe that will make a big impact on people’s lives.”