A look at how Bangalore can meet its growing water needs

Bangalore is not new to water problems: the city’s water consumption is monstrously growing and its groundwater levels are rampantly depleting. Water pollution levels are a matter of grave concern, with Bellandur and Varthur lakes intermittently catching fire and spitting froth. The demand for water is snowballing day after day owing to the city’s exponential growth, initiated by its global rise as a major technological hub of India. As reported by Bangalore Mirror, the city’s population grew from 8.4 million in 2011 to a staggering 12 million in 2018, recording a whopping 30 percent growth rate in just seven years. A 2018 BBC report listed Bangalore as one of the world’s 11 cities likely to run out of drinking water before long.

How long can a city like Bangalore, with a swelling population and never-ending property developments, feed on external river sources? Offering solutions to the crisis is AR Shivakumar, a former scientist at Karnataka State Council for Science and Technology (KSCST) at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc). Solely relying on the collected rainwater for all of his family’s needs, he claims to not have used a single drop of municipal water in the last 24 years. His cost-effective rainwater harvesting (RWH) design and water management ideas implemented at his home could mitigate Bangalore’s water woes.

The city’s water needs and sewage system have been managed by the civic water body – Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB), set up in 1964. Since its inception, BWSSB has implemented various projects to procure water and cater to the city’s needs. Presently, a major portion of the water supplied to the city is being imported from the River Cauvery. The occasional water shortage is met by drawing water from borewells. As per the BWSSB figures, Cauvery water supply to Bangalore at the moment stands at 1,400 million litres per day (MLD). Further, to meet the water demands of the ever-expanding city, the Karnataka state government has allotted additional 10 thousand million cubic feet (TMC) of water through Cauvery Water Supply Scheme Phase V and 2.5 TMC water from the River Nethravathi through Yettinahole project. These projects, estimated to be completed by 2023, will provide an additional 975 MLD supply to the city. In addition, the state government plans to pump water from the River Sharavathi to Bangalore, which is being opposed by the locals and environmentalists.

This condition prevails despite Bangalore receiving rainfall almost round the year

This condition prevails despite Bangalore receiving rainfall almost round the year. It receives an average annual rainfall of 970 mm distributed over eight months from April to November, while months from December to March are usually dry. Endowed with a naturally undulating terrain of hills and valleys, Bangalore serves as an ideal locale for gathering and storing rainwater.

Shivakumar’s first experiment

It is in this context that Shivakumar’s experiments on rainwater harvesting, which began while building his house in 1995, hold promise. At the time, he was working on various renewable energy projects at KSCST while also popularising rooftop solar water heaters. But before endorsing them to the public, he realised that he had to be convinced of their sustainability. “Unless you are happy with the technology you are promoting, it’s not going to take off,” he asserts. Consequently, he constructed his house incorporating all conceivable environment-friendly measures.

Through rainwater harvesting, he calculated that he could collect over 2 lakh litres of rainwater annually, which was more than sufficient to fulfil his family’s needs

To begin with, Shivakumar researched people’s daily water consumption, according to the World Health Organisation standards. He estimated that his family of four would require around 1.8 lakh litres of water in a year. He also collected Bangalore’s rainfall data from the last 100 years and studied the monthly rainfall pattern. Through rainwater harvesting, he calculated that he could collect over 2 lakh litres of rainwater annually, which was more than sufficient to fulfil his family’s needs. But he had to first figure out means to store the water. Soon, he worked out a solution: “To my surprise, I found out that there is hardly 100 days gap between two good successive showers of rain in Bangalore. So we planned to store 45,000 litres of rainwater to bridge through these 100 days,” he explains.

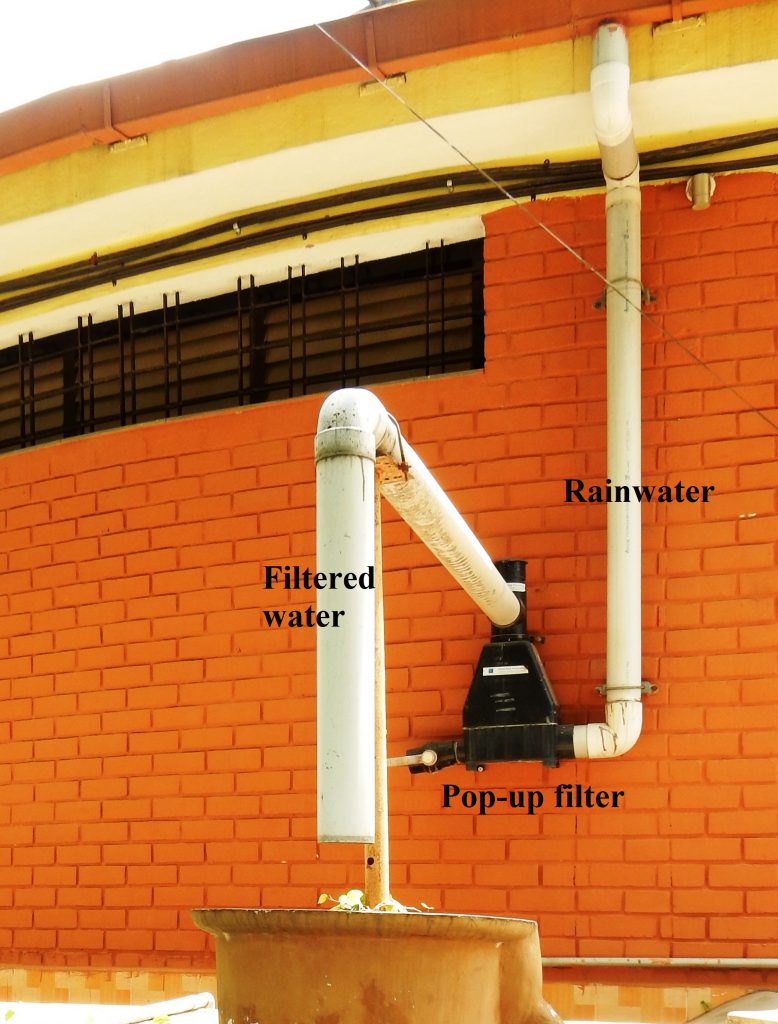

To design his rainwater harvesting plant, he built a chain of storage tanks to stock the collected rainwater from the rooftop, diverting excess water to a shallow borewell. His plant amasses every drop of rainwater falling in the open spaces and directly recharges the underground water table, through the many percolation pits dug around his house in the garden. Since the rainwater falling on the roof gets mixed with dirt, leaves, bird droppings, and the like, Shivakumar designed (and patented) a simple pop-up filter which can be vertically mounted on the wall. This pop-up filter consists of a rainwater inlet, flush valve, filter element, and an outlet for filtered water. In the initial minutes of raining, rainwater is directed through the flush valve which lets the dirty rainwater flow out. After about five minutes, the flush valve locks automatically, pushing the water up through the filter element. The clean water then flows through the outlet and into the storage tank.

The cost incurred for building an RWH unit can be divided into three parts – installing channel pipes, filtration unit, and storage tank or percolation pits. Pre-mounted channelling pipes are used to drain water flooded on the roof. A pop-up filter costs around Rs 6,000 and the number of filters required depends on the volume of rainwater. A major portion of the expenditure goes into building the storage tank (which can be minimised further if the tank is built during the construction of the house itself). Houses or complexes devoid of space to build storage tanks can opt for installing recharge wells to inject rainwater into the ground – it requires very less space and money. When asked if it is cumbersome to maintain the installed RWH unit, Shivakumar states, “If you keep your roof clean, half the job is done. In addition, maintaining the filters as per manufacturer’s specifications ensures clean water in tanks.”

“If you keep your roof clean, half the job is done. In addition, maintaining the filters as per manufacturer’s specifications ensures clean water in tanks”

The bigger goal

Shivakumar’s experiments don’t just end with harvesting rainwater. Besides adopting minimal water consumption practices, his family recycles wastewater for secondary purposes like gardening and toilet flushing. Used water from the kitchen sink is collected in a container to water plants. Shivakumar has devised a simple, low-cost wastewater treatment unit on his roof for recycling grey water. The unit contains an aeration system, which removes bad odour from the used water coming in from the washing machine. Water is then stored in two open tanks with suspended plants growing on top to absorb detergent chemicals. The collected water is relatively clean and is used for toilet flushing.

Along with an elaborate water management system, Shivakumar has also implemented many electricity conserving measures. He has installed solar water heaters and solar-powered LED lights. To insulate his house – keeping it cool during summer and warm during winter – he used rat-trap walls (placing bricks in a way to leave a three-inch gap inside the walls). Plant cover around his house naturally air conditions the house in summer. The house is planned to allow ample light even to the interior parts, rendering the use of electrical lights during the day unnecessary.

A crusade for harvesting rain

After building a sustainable rainwater harvesting model at his home, Shivakumar became a strong advocate for RWH units. He led the rainwater harvesting division at KSCST by building prototypes and popularised the idea of rainwater collection across Bangalore and other parts of Karnataka. He was actively involved in the design and execution of RWH projects in landmark buildings such as the Vidhaana Soudha, High Court, Kidwai Hospital; and in government organisations like BWSSB, IISc, and Gandhi Krishi Vignana Kendra, to name a few.

Due to his continual efforts, he could persuade BWSSB to establish Sir M Visvesvaraya Rain Water Harvesting Theme Park at Jayanagar in 2011. Spanning over 1.2 acres of land, the park exhibits 26 different rainwater harvesting models, along with demonstrations of water conservation techniques, designed and developed by Shivakumar and his KSCST team. Help desks are set up at both the theme park and KSCST to provide information on rainwater harvesting to visitors. The centre has been conducting mass awareness programmes and provides technical training programmes on the execution of RWH methods to contractors and plumbers.

Shivakumar was instrumental in bringing about changes in BWSSB policies to make the rainwater harvesting mandatory in Bangalore

Shivakumar was instrumental in bringing about changes in BWSSB policies to make the rainwater harvesting mandatory in Bangalore. The BWSSB amended section 72 of Karnataka Act 36 in 2009, wherein harvesting rainwater was made compulsory for all buildings – measuring 2400 sq. ft. and above, if constructed before 2009; and measuring 1200 sq. ft. and above if constructed after 2009. In 2017, BWSSB made installation of sewage treatment plants (STPs) mandatory in apartment complexes with more than 20 units. However, citizen groups resisted the rule and it resulted in the exemption of apartments with less than 50 units. Currently, BWSSB is operating 14 STPs treating 721 MLD of wastewater. Treated water from these plants is discharged to replenish lakes and is utilised for non-potable purposes like cleaning, gardening, and construction. BWSSB also supplies this treated water to the public at subsidised rates to reduce the dependency on freshwater.

The road to a sustainable Bangalore

The civic body plans to induct RWH units in most of the state buildings, public parks, road pavements, and wherever feasible, showing that they are slowly warming up to the idea of collecting rainwater comprehensively. As per BWSSB, harvesting even 50 percent of the city’s incident rainfall adds 10-15 TMC of water to the reservoir, adequate to sustain the supplementary demands.

Although BWSSB issues notice to those who don’t comply with installing RWH units, residents have not strictly implemented it

But convincing the residents on its merits is still a challenge. Although BWSSB issues notice to those who don’t comply with installing RWH units, residents have not strictly implemented it. BWSSB started penalising the offenders from February 2017 and the collected penalties (varying from 50 percent to 100 percent of total water bill) amounted to Rs 2.93 crore per month, as on May 2019. Elaborating on the situation, Shivakumar thinks that the easy availability of municipal water and the lack of restrictions on drawing underground water are to be blamed. “Why would they go for tedious options when they get clean water delivered to their doorstep at cheaper rates? Keeping the minimum price for the basic needs, the fares should be substantially raised for luxurious needs. Only then people will choose water-conserving measures,” he adds.

In response, an engineer at BWSSB says that increasing tariffs don’t always work. He explains, “People’s views have to be considered while taking major decisions like increasing fares; otherwise they will protest.” Some parts of Bangalore, he adds, are more open to RWH units than the others. “While some residents enthusiastically adopt RWH measures, some just set it up to abide by the law. The extended areas in the city’s outskirts – where the BWSSB does not supply water and [where] groundwater is receding [due to unrestricted groundwater usage] – are increasingly switching to rainwater harvesting as compared to inner-city where BWSSB supplies water.” The quantity of rainwater being harvested in Bangalore at present (storing and groundwater recharge inclusive), according to his estimate, is less than 10 percent – far lesser than the 50 percent target set by BWSSB.

Neelima Basavaraju, a former postdoctoral researcher at IISc’s Solid State and Structural Chemistry Unit, is a freelance writer

To read more articles in our series on the monsoon, click on the following links:

Sulochana Gadgil: A Lifetime of Monsoon Research

MONTBLEX: India’s First Major Monsoon Experiment

Interview with Syed Ameenulla: ‘Ours was a small group, like one family’

BoBBLE: ‘An Unusually Successful Cruise’

What an Adivasi Village in Chhattisgarh Can Teach Us about Sustainable Development

Decoding the Signatures of Monsoons Past in Fossils and Genes

Chanchal Uberoi on Monsoon Melodies

Why Knowledge Isn’t the Barrier to Water Conservation