A scientist and his small team of volunteers have steered the cause of plants by creating a unique database, an important first step in the battle for species conservation and habitat restoration

On the third floor of IISc’s Biological Sciences building is a room which, at first glance, may seem like a computer science lab. But only one half of the room has computers, while the other half has old newspapers, roughly A3-sized thin cardboard sheets called herbarium sheets, blotting sheets and stationery strewn around. And in the corner of that portion is a Press, a

piece of equipment used for pressing plant specimens brought from the field.

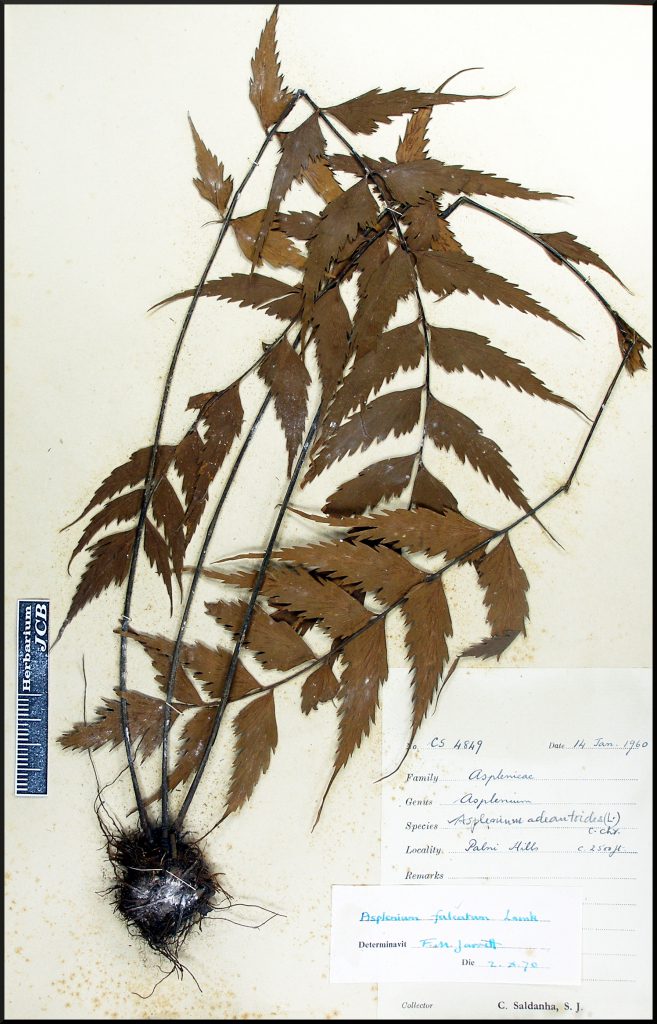

Noel Sebastian, a project assistant, who is just back from a field trip, stacks plant specimens between newspapers and places them on the Press. On a table beside the Press is a bunch of herbarium sheets that have dried plant specimens pasted on them. These sheets are also labelled: the date of collection, the family, genus, and species to which it belongs, and habitat where it was found, along with the names of the collectors. The herbarium sheets are stored for posterity in the specimen repository, Herbarium JCB (Joseph’s College Bangalore) in the Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES). Sebastian and his colleagues now have the mammoth task of digitising these collections. Once digitised, the information becomes part of a massive database which is at the heart of three websites that have so far been launched by CES that are accessible for free: Digital Flora of Karnataka in 2014, Digital Flora of Peninsular India and Digital Flora of Eastern Ghats in 2019.

Herbarium JCB has collections from all over Karnataka and is a new avatar of what was first set up by the late Cecil J Saldanha, a botanist who taught at St Joseph’s College, Bangalore. After retiring, he moved to the CES, and with him, his herbarium. The eminent botanist died in 2002, leaving behind a rich collection of plant specimens. Eventually, in 2007, the mantle of taking the herbarium forward rested on Sankara Rao, who had retired from IISc’s Department of Biochemistry.

The database is expanding not just because of Rao’s team but also other botanists excited about the project. “I thought there was a lot of information in the herbarium in the form of a collection of plant specimens with data on each of [the] 20,000 specimens. I thought I can compile it into a database, instead of bringing this out in a printed form,” he says.

Eventually, the mantle of taking the herbarium forward rested on Sankara Rao, who had retired from IISc’s Department of Biochemistry

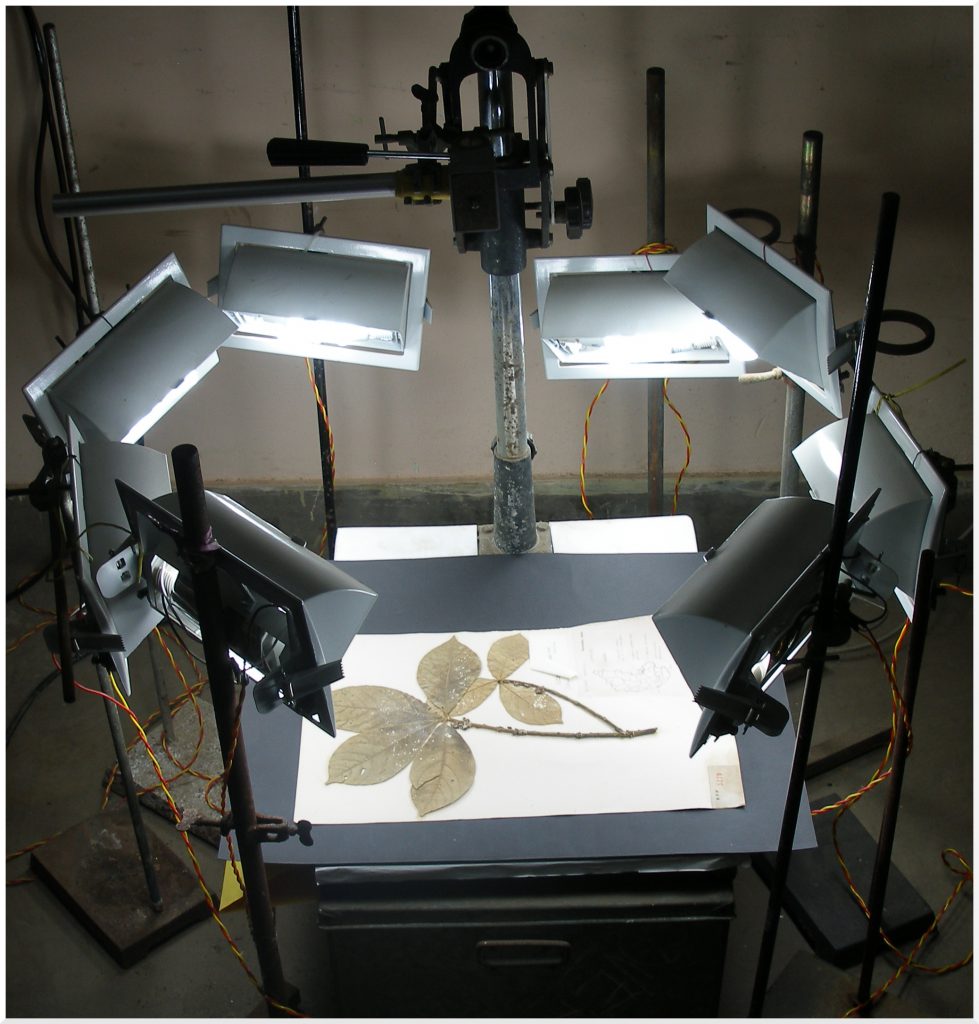

So among the first things that Rao did was to present his vision for the herbarium to CES in 2008. “I talked about it in the wake of India losing its diversity, habitats and how this information could be used in creating awareness,” he says. “With some help, I created a database of 100 species and showed how with the click of a button, people can access information on plants.” Most people in the audience were impressed and CES gave him the go-ahead to digitise the herbarium. They also provided him with the necessary infrastructure: storage facilities, an anteroom, a few computers and a project assistant. Thus began the laborious process of expanding and digitising the herbarium.

Field trips

In this process of creating the digital herbarium, the team added another crucial feature, through which they could update changes in plant diversity. Rao says, “Some plants collected for the herbarium are 30 years old. In that span of time, we can expect a considerable change in the habitat or the vegetation.” One way of going about it is to revisit areas that were

surveyed earlier to document changes in plant distribution.

A visit to Ottinene in Udupi district about six years ago by the team, illustrates the importance of field trips. Arun Singh, who was then a part of the team, found that certain flowering plants belonging to the genera Ceropegia and Eriocaulon had disappeared from the region, even though herbarium records mention its presence in Ottinene. His trip to Jenkal

Betta and Bisle in the Western Ghats also proved futile, as he couldn’t spot the indigenous trees Isonandra stocksii and species of Cynometra andHopea, indicating that these plants may have been wiped out in that region.

In addition to its use in monitoring changes in species distribution, field expeditions have also opened doors for discovery: A member of Rao’s team, Raja Swamy, has identified three new species and rediscovered six species that were once thought extinct. Singh also recalls finding plants that were stated as endemic to Kerala such as Paracroton integrifolius and Atuna indica in Karnataka.

But field explorations are not as glamorous as they sound. Swamy recalls being chased by two elephants during his recent trip to Thithimathi in Kodagu. The forest guards managed to scare the elephants in time. Encounters with wildlife or poisonous insects aren’t the only challenge; they often work under the scorching sun or in heavy rains – they have even

found themselves in the midst of flash floods.

Making of herbarium sheets

Once plants are collected from the field, they go through a few stages of processing. Rao explains, “This is important to preserve the collected plant specimens, especially woody ones as they lose their leaves, flowers and fruits, soon after they are separated from the plant. We also do this to avoid fungal contamination.” This step happens in the field, where they kill all of the collected specimens by dipping them in either alcohol or formalin.

The collected samples − carefully placed between blotting sheets or newspapers − make their way into the anteroom of the herbarium. It is here that the next stage of processing begins.

Rao’s team then stacks a bunch of specimens on the Press to flatten and dry them. “We paste or stitch the dried specimens on the herbarium sheet, along with the numbers assigned to them on the field. My team enters collection details on the herbarium sheets and in the database,” he explains. “We then store these specimens [sheets] in our herbarium, where they are placed alphabetically in their designated cupboards.”

Going digital

Not long after Rao began his initiative, he realised that although he and his team had expertise in the areas of botany and ecology, computer programming – essential to creating a digital database – wasn’t their forte. Fortunately for him, he found much-needed support from Deepak Kumar, a former PhD student from the Electrical Engineering Department.

“We have profiled about 10,000 species in Peninsular India and about 4,500 species in the Eastern Ghats”

It took the team seven years to share their first database with the outside world. When they launched the website on the flora of Karnataka in 2014, they made sure that information about every plant in the online database had been peer-reviewed by experts in the field.

Rao, however, wasn’t ready to rest on his laurels. The team then set their eyes on surveying species that inhabit the rest of South India, setting the stage for more collaborations and field trips, not to mention the laborious process of preparing and digitising new herbarium sheets. In 2019, Rao’s team launched their second and third websites. Elaborating on the projects, Rao says, “We have profiled about 10,000 species in Peninsular India and about 4,500 species in the Eastern Ghats, all of which can be accessed by clicking on the alphabetically sorted list in the database.” By clicking on a species, you will find details such as its technical name, vernacular name and common name.

Those visiting the website can also view scanned herbarium sheets and photos from field trips. Calling this the first version, Rao says that his team will continue updating it. The website also allows people to reach out to the team by sending in their comments, queries or suggestions. He encourages people to write to them if they spot changes in plant diversity, which he says will be verified by the team.

The database is expanding, thanks to a few botanists. Recently, Rao forged ties with SP Khullar from Panjab University, who has authored a book on Western Himalayan ferns. “He has agreed to share information about ferns particularly from the Western Himalayas, helping us broaden our database,” he says. Swamy adds that the herbarium of the Regional Plant

Resource Centre, Odisha, has also contributed to this effort by sharing their entire collection of plants from Odisha. “I went to Bhubaneswar, scanned all of them, and brought them to IISc. This has now become a part of the Herbarium JCB.”

Plant conservation

Rao also claims that his websites can play an important role in species conservation and habitat restoration. “The website provides information on species and their spaces: district- and state-wise locations, types of habitats and species that grow in these habitats, their conservation status, and whether a species (endemic) is restricted to a particular location. Additionally, information on indigenous plants present on the website can strengthen afforestation efforts.” Because habitat destruction causes wildlife to stray into human habitation, he believes that habitat restoration can also reduce human-wildlife conflicts.

Rao is concerned that certain species will be exploited for commercial interests, which is keeping him from releasing the GPS data of each of the documented species

Data from the websites can also serve as the baseline in studies which track changes in plant diversity over time. For instance, Rao’s team recorded dwindling numbers of India’s own living fossils: plants belonging to the genus Cycas. Considered one of the oldest living plants, they date back to 200 million years, some of which are present in small pockets in Karnataka. “While their contemporaries, the dinosaurs, are not alive, these plants are alive. Peninsular India has its own indigenous species: Cycas indica, C. beddomei, C. swamyi, C. sphaerica. C. indica remained undiscovered until 2007 and C. beddomei is seen only in Tirumala hills. These plants are now being misused: the locals cut their leaves and sell them to florists, who use them to make bouquets,” he says.

Rao also has concerns that certain species will be exploited for commercial interests, which is keeping him from releasing the GPS data of each of the documented species online. But he is open to sharing this information if he is convinced that it will not be misused.

As for the plans he has envisioned for the herbarium, Rao continues to be ambitious – his team will soon be gathering data from parts of central India. To do this, he is joining forces with botanists from other parts of India, including Pradip Krishen, who works on habitat restoration. He is keen on including species from north India as well, all of which requires abundant funding − the biggest deterrent to this project.

The herbarium needs more funds for field trips as well as to attract experts to work there

“Each field trip costs Rs 40,000 to 60,000,” says Swamy, about field visits they do in the South. But Rao adds that they’d need to shell out more to fund trips they make to the north.

Rohini Balakrishnan, Chair of CES says, “He [Rao] developed this digital database, essentially single-handedly, with the help of a small team of volunteers, without any kind of monetary remuneration. He did this on an absolute shoestring budget that we could provide him and with fairly primitive equipment, much of which he rigged up himself and paid for himself.” The herbarium needs more support not just for field trips but also to attract eminent experts to work at the herbarium. It has, however, made a good start. Recently, the herbarium received a generous grant from Lakshmi Narayanan, former CEO and vice chair of Cognizant Technologies.

Besides funding, the group has had some hitches in getting permissions from government agencies and forest officials. They have even been sent back several times from field sites. Rao, however, is optimistic that things will change. “We’ll show the world what we have done. And on that basis, we can hope for more help and funding.”