The State of Mysore played a crucial role in helping establish IISc and influenced its research in the years that followed

“Mysore is the best administered state in the world,” John Sankey, the Lord Chancellor of Great Britain and a human rights activist, is said to have declared during the first Round Table Conference in London in 1930, one of three peace conferences called by the British Crown to discuss constitutional reforms in India. While Sankey’s claim might sound like hyperbole, Mysore did indeed make exceptional progress from 1881 to 1950, the year monarchy was abolished, thus laying the foundation for the emergence of Karnataka as an industrial, and more recently, an IT hub.

In March 1881, the Wadiyars resumed their innings – to use a cricketing analogy – as the rulers of the state after they signed the Agreement of Rendition with the British Government of India, which had ruled Mysore directly for several decades. But the royal family took over at a time when the state of affairs in Mysore was precarious.

Mysore’s rulers believed that educating its people was indispensable for modernisation and set up several educational institutions across the state

From 1837 to 1900, India was struck by repeated famines, eight of which were considered major famines. They were brought about by droughts, plagues and the agrarian distress following the introduction of the zamindari system by Lord Cornwallis. One of these, called the Great Famine of 1876-78, is thought to have killed between six to 10 million people, mostly in southern and south-western India.

Mysore was severely affected by the famine. The extent of distress was revealed in a speech that CV Rangacharlu, the Dewan of Mysore, gave to the newly constituted Representative Assembly – a quasi-democratic body – in October 1881. According to him, the state had lost nearly 20 percent of its population and a substantial proportion of its livestock to the famine. Vikram Sampath, in his book Splendours of Royal Mysore: The Untold Story of the Wadiyars, writes that the state’s debt stood at a whopping Rs 80 lakh.

However, in the years that followed, Mysore was able to extricate itself from this perilous situation and it eventually found itself on the path to progress. The achievement is all the more remarkable considering the severe constraints imposed upon it by the Rendition Agreement, not to mention an annual “protection” fee it had to pay the British Government of India. Sampath attributes the state’s development during this period to the foresight of its rulers: Chamarajendra Wadiyar X, Kempananjammani Vani Vilasa Sannidhana, Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV and Jayachamarajendra Wadiyar. But he also highlights the crucial role played by the Dewans, or Prime Ministers, of the state in bringing about this transformation through their administrative reforms. Sampath singles out the contributions of the famous quartet of Dewans: Rangacharlu (1881-83), K Seshadri Iyer (1883-1900), M Visvesvaraya (1912-1918) and Mirza Ismail (1926-1941).

During this period, Mysore’s rulers believed that educating its people was indispensable for modernisation and set up several educational institutions across the state. Perhaps the most significant project they involved themselves in was Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata’s ambitious initiative to establish a world class research institute in India.

Mysore’s initial involvement was through Seshadri Iyer, who was well-acquainted with Tata. He had helped the industrialist procure land for a silk farm in Bangalore in the early 1890s. Mysore had also provided subsidies for Tata’s sericulture experiment. (Though the farm no longer exists – it was sold to the Salvation Army after Tata’s death – it lent its name to Tata Silk Farm, a neighbourhood near Basavanagudi.) This successful partnership between Tata and Mysore in South Bangalore served as a precursor to a more consequential collaboration in the coming years, leading to the creation of IISc, in the north of the city.

The seeds of the plan to establish what came to be known as IISc were sown in Tata’s mind at a time when there were no true institutions of higher learning in science and engineering in India. A notable exception was the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Sciences, which was founded by the enlightened medical doctor and social reformer Mahendralal Sarkar in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1876. But even this association – “devoted to the pursuit of fundamental research in the frontier areas of basic sciences” – was not supported by the government; it relied on public contributions.

The government was instead more interested in setting up bodies whose responsibility was merely to conduct examinations and grant degrees to students in affiliated colleges in major cities, bodies they referred to as universities. The curricula in these colleges focussed mostly on teaching English and the humanities. It was the general policy of the British Government of India not to establish technical schools devoted to science and engineering on a large scale, says BV Subbarayappa, a historian of science, in his book In Pursuit of Excellence: A History of the Indian Institute of Science.

It was under these circumstances that Tata decided to contribute to the growth of science in India. In his many travels to Europe and North America, Tata had seen first-hand the role of scientific research and higher education in economic and social transformation. He was also aware of the role of philanthropy in building universities. By the 1890s, Tata, who had become an enormously successful industrialist, was ready to use his personal wealth for causes that he believed would improve human welfare. He had also evolved his own philosophy of “constructive” philanthropy.

Tata elaborates on his idea of philanthropy and his motivation to contribute to higher education in India in an interview to the newspaper West Coast Spectator, quoted in Frank Harris’ book Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata: A Chronicle of his Life. He says, “What advances a nation or community is not so much to prop up its weakest and the most helpless members, as to lift the best and most gifted so as to make them of the greatest service to the country. I prefer this constructive philanthropy which seeks to educate and develop the faculties of our young men.”

Though Tata conceived of his university idea in the early 1890s, it was only in 1896 that he began the groundwork on the project. And it wasn’t until 1899 that Mysore became an active player. Tata, who was on a tour of South India earlier that year, paid his friend Seshadri Iyer a visit. During their discussion, he apprised the Dewan of his plan. He also expressed two major concerns he had: finding a suitable location – there were several contenders including Tata’s hometown Bombay – for the “Imperial University of India”, as it was then called, and the need for additional financial support. The anticipated cost of setting up and running the university was more than the expected income from Tata’s endowments.

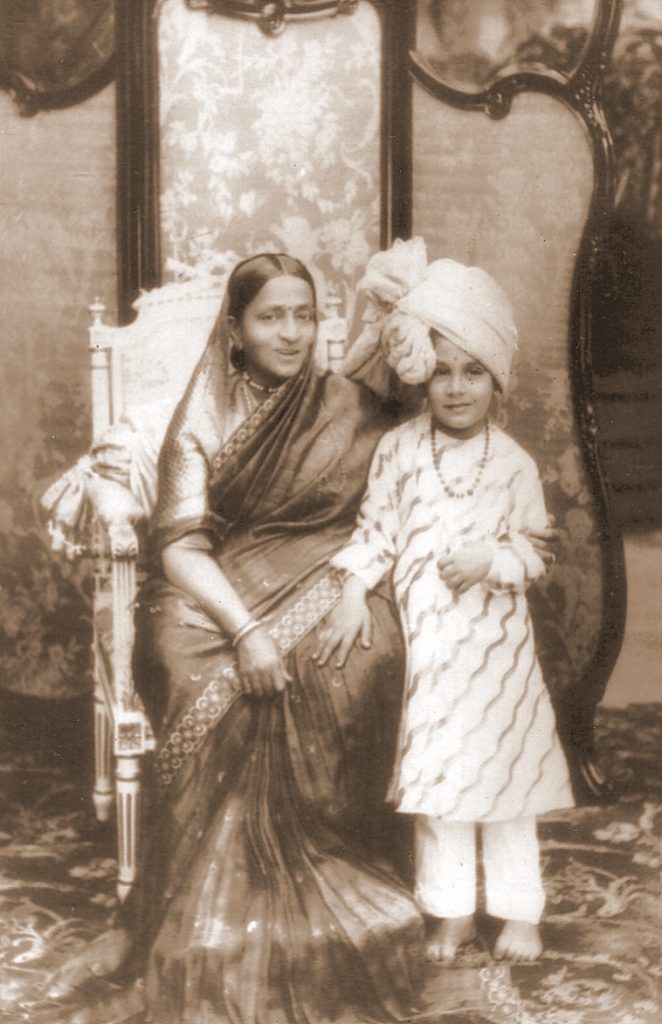

Soon after Tata’s visit to Bangalore, Iyer consulted with Maharani Kempananjammani Vani Vilasa Sannidhana (her son Krishnaraja Wadiyar was a minor then) about whether and how Mysore could help Tata. The Regent Queen was easily convinced of the need to support Tata’s grand idea. She also agreed to provide land and money for the project. Iyer immediately conveyed Mysore’s decision to the Provisional Committee put together by Tata with the mandate of implementing his vision.

Even though Mysore’s proposition did not have any specifics at this point, it was taken seriously by the committee as well as the government. Mysore’s offer of financial help, however, was conditional: the proposed university had to be in Bangalore. Mysore’s insistence on Bangalore and the city’s attractive climate made it the front-runner to host the university by the end of the Simla Conference held in October 1899, a meeting called for by the government to discuss Tata’s proposal. Bangalore also received a fillip, when in the following year, William Ramsay, the noted British chemist, gave his thumbs-up to the southern city in a report he prepared. Ramsay had been chosen by the Provisional Committee to make specific recommendations about the proposed university or “Institute” as he called it.

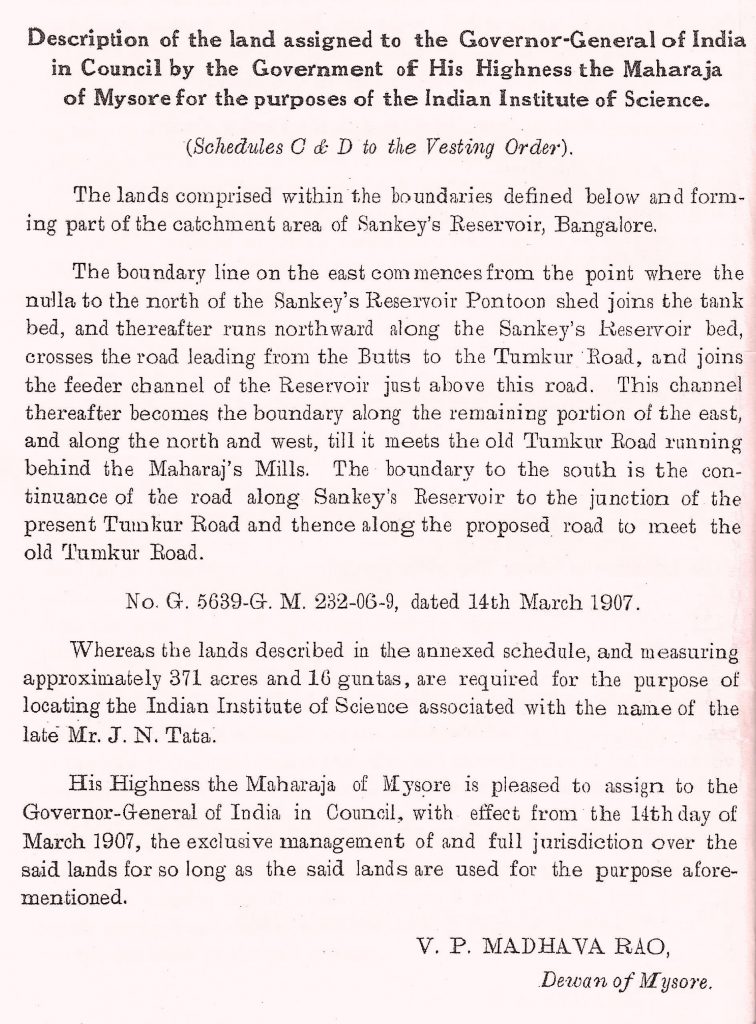

Mysore, in the meanwhile, firmed up its commitment – it promised 371 acres and 16 guntas of land in Bangalore, Rs 5 lakh towards capital expenditure, and also an annual contribution of Rs 30,000 (which was increased to Rs 50,000 in 1905). Its proposal was accepted by the government, but several hurdles had to be overcome before IISc came up, including those resulting from Tata’s untimely death in the summer of 1904. On 14 March 1907, VP Madhava Rao, Mysore’s Dewan, officially handed over the land that was promised by the state. And on 27 May 1909, IISc finally came into existence following a vesting order and resolution passed by the British Government of India to establish the Institute.

After IISc was set up, it continued to benefit from Mysore State in many ways. The state’s most direct involvement was through its Dewans, who were ex-officio members of the Governing Council of the Institute, one of the two decision making bodies of IISc (the other being the Court).

The most influential of Mysore’s representatives to IISc was Visvesvaraya, who replaced T Ananda Rao in the Council in 1913. Back in 1907, Visvesvaraya, already a celebrity engineer, had outlined his plan for the economic development of the state in his manifesto A Vision of Prosperous Mysore. When he became part of the Council, he saw a role for IISc in helping Mysore modernise. “Visvesvaraya, known for his dictum ‘Industrialise or perish’, was deeply interested in the industrialisation of Mysore State. His association with the Institute had its impact on the applied researches of the Institute,” claims Subbarayappa.

Several industries came up as a direct result of research conducted at IISc

In the next five years, several industries came up as a direct result of research conducted at the Institute, according to IISc’s Annual Reports. These included an acetone factory in Nasik, a thymol factory in Hyderabad (Sindh), a factory to make straw boards from bamboo in Bangalore, a soap factory in Bangalore and sandalwood oil factories in Bangalore and Mysore city. The Institute also provided technical help to Hyderabad State for producing alcohol from mahua flowers and to the Mysore Spinning and Weaving Mills in Bangalore to make a durable textile dye using sappan wood (wood from a local leguminous tree) and catechu (an acacia extract).

The most successful of the industries were the sandalwood oil factories and the soap factory, which ensured that the wood and its products became synonymous with the state of Mysore, and eventually Karnataka. IISc’s Annual Reports also detail how these factories were set up, a testimony to the encouragement and the influence exerted by Mysore in those years.

In 1914, Mysore State found itself with surplus sandalwood; World War I had broken out and exports to Europe ceased. It then requested IISc to carry out research to extract oil from sandalwood.

Experiments at IISc were led by JJ Sudburough, a professor in the Department of General Chemistry, who had moved from the Department of Organic Chemistry, and HE Watson, an assistant professor from the same department. They were joined the following year by Venkataranga Iyengar and K Parthasarthi. Impressed with the research, Krishnaraja Wadiyar provided funds in 1916 to establish an experimental factory in the vicinity of IISc to manufacture sandalwood oil. Mysore also offered scholarships and deputed two students, B Rajagopal and B Sunderaraj Iyengar, to undergo training in the Institute. In 1917, they were given jobs as Assistant Chemists in the sandalwood oil factory nearby. Sudburough and Watson were also appointed as Consulting Chemists of this factory.

In the same year, Krishnaraja set up the second sandalwood oil factory in the city of Mysore. Meanwhile, another team of researchers comprising J Chakraborty and GA Mahmadi conducted experiments on making soap with local oils. Again, pleased with the results, Mysore set up a 5-tonne soap plant near the Institute. Much of the soap produced during these years was sent to British troops in Mesopotamia by the Red Cross Society. This experimental unit then gave way to a bigger and newer soap factory in early 1918. Later that year, the first Mysore Sandal Soap was introduced in the market.

Visvesvaraya’s tryst with IISc continued long after he gave up his position as the Dewan. He returned to IISc in 1938, when he was elected as the President of its Court, a position he retained until 1947. Visvesvaraya saw World War II as an opportunity for the Institute to refocus its efforts on doing research that would benefit the Allied forces, thus boosting the manufacturing sector. His words, once again, seemed to have an immediate effect on research priorities in IISc.

The 1940s was also a period when IISc expanded rapidly, particularly in areas of applied research, under its Director JC Ghosh. As the war was drawing to a close, the focus of the Institute shifted to nation-building, something that Visvesvaraya was keen to drive. It was during this decade that several new engineering departments came up in IISc: Aeronautical Engineering, Chemical Engineering, Metallurgy, Internal Combustion Engineering, Power Engineering, and Electrical Communication Engineering (it was earlier a section in the erstwhile Electrical Technology Department).

In the initial years of IISc, grants from Mysore were the largest by far that the Institute would receive, and in the years to come, the largest from a local government (only grants from the government of India were larger in subsequent years). Mysore also offered periodic grants and scholarships to students. For instance, the 1943 Annual Report shows that it provided Rs 1 lakh to the Institute – Rs 50,000 towards “normal” expenses and Rs 50,000 as capital grant for the institution of the Aeronautical and Automobile Engineering Sections. It also awarded two scholarships for students in the newly started course in Aeronautical Engineering.

Though it was the Dewans who had a more direct say in the running of the Institute, Mysore’s Maharajas made it a point to visit the Institute regularly and offer their counsel. On 1 February 1911, a few months before the Institute opened its doors to its first batch of students, Krishnaraja Wadiyar came to IISc to lay the foundation stone of the Main Building. Speaking on the occasion, he praised the generosity of his mother for providing land and money to help make Tata’s dream come true. He also used the opportunity to urge the Institute not to restrict scientific research to students of “independent means” and consider providing scholarships to those “who have no capital at their backs.” (The entire speech is reproduced in this magazine.) His plea was taken seriously by the Council. In 1914, IISc announced that it would be offering 11 scholarships to economically disadvantaged students.

A few years later, on 10 March 1922, it was again Krishnaraja who was invited to the Institute to unveil the monument dedicated to its founder. He was accompanied by his brother, Yuvaraja Narasimharaja Wadiyar, who also maintained an association with IISc. The Yuvaraja’s son, Jayachamarajendra Wadiyar, Krishnaraja’s successor to the throne, kept up the tradition of coming to IISc, even after he ceased to be the Maharaja in 1950 (he however continued to hold the title till his death). In 1958, besides inaugurating the open-circuit wind tunnel of the Aeronautical Engineering Department, he was also the chief guest for IISc’s Golden Jubilee celebrations.

Even though Mysore’s formal association with IISc ended with the abolition of monarchy, its legacy has endured. A close reading of the events that led to the establishment of IISc and its early years suggests that, without the backing of Mysore, IISc might still have come up. But the princely state’s involvement in Tata’s ambitious project ensured that it ended up in Bangalore. Moreover, Mysore’s close association with IISc also influenced the size of the Institute, the nature of its research, and the scale of its impact.

For more stories about IISc’s connection to the princely state of Mysore, follow the links below:

Who Was Kempananjammani Vani Vilasa Sannidhana?

The King’s Speech: ‘The Underdog as Scientist’