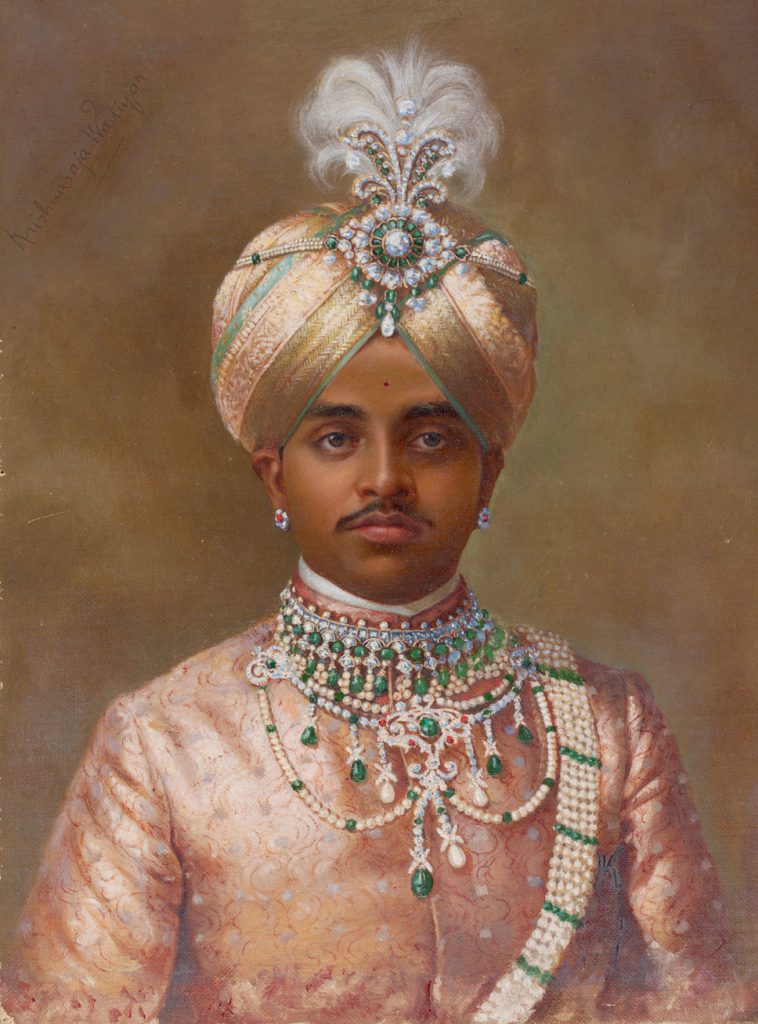

The following extract is a speech made by Krishnaraja Wadiyar, the Maharaja of Mysore from 1894 until 1940, at a ceremony to lay the foundation stone of IISc’s Main Building in 1911

Very deep is the responsibility which has fallen on me to-day of laying the Corner Stone of these magnificent buildings, the future home of an Institute which will be unique of its kind in India. I need not remind you that the India of to-day is almost entirely an agricultural country and that except in a few centres, such as Calcutta and Bombay, the large industries, which contribute so much to a nation’s wealth and which are such a marked feature of Western civilisation, are practically non-existent. An agricultural population must of necessity be poor, as compared with an industrial one, and this poverty, in the case of India, is accentuated by periodical visitations of famine due to an uncertain rainfall. It is of course beyond the efforts of man to change the face of our vast Peninsula and to alter the conditions of life of its teeming millions of agricultural labourers, but nevertheless it should be possible by dint of sustained and well-directed efforts to improve the position of the working classes by not only expanding our existing industries but increasing their scope and number and in this way reducing the number of people who are dependent on the soil for a livelihood. Living under the conditions which surround him in India, every thinking man cannot but welcome a scheme like that of the Indian Institute of Research* which has as its object the development of Arts and Industries on scientific lines and I feel that I am echoing the voice of thousands of my fellow countrymen when I publicly acknowledge to-day the deep obligation which we owe to that eminent philanthropist Mr JN Tata to whose fore-sight and liberality is due the inception of this great scheme of an Indian University of Research, and to his sons and successors who have so readily and generously come forward to carry out their lamented father’s wishes.

It is not too much to say that the family of Tata will be remembered by the people of India for many generations to come as princely benefactors and as distinguished members of that enterprising and virile race who have been among the pioneers of the commerce and industry of Western India.

‘The Institute should make some provision for students, who, though they possess no capital, are likely to turn a scientific training to useful account’

I cannot help reflecting with pride that it is due to the public spirit and fore-sight of my own mother, when she was Maharani-Regent, that the Mysore Government occupies today a prominent position among those who have come forward to supplement the Tata family’s original endowment, and has provided not only a building site and a portion of the building grant but also an assured annual for the upkeep of the Institute. Mysore will, I feel sure, reap a reward from the liberality of HH the Maharani-Regent’s Government by having at her doors an University which will teach her sons to increase the material wealth of their country. Sir Dorabji Tata pays a just tribute to the late Sir K Seshadri Iyer, who was my mother’s trusted adviser in this and all other matters connected with the welfare of the Mysore State. I would like, before I conclude, to draw attention to one rather important point in the Director’s address.

I refer to the question of scholarships. No doubt, it is to a certain extent a wise policy to try and restrict scientific research to students of independent means and to discourage a class of students who have no capital at their backs and therefore no prospect of making practical use of the knowledge acquired at the Institute, but it must not be forgotten that if a hard and fast rule is made against the grant of scholarships, the result may be to shut out an occasional student who has brilliant abilities without the means of supporting himself during his course of study at the Institute. It may also be fairly argued that the Institute should make some provision for students, who, though they possess no capital, are likely to turn a scientific training to useful account as salaried employees under capitalist manufacturers. There is of course a wide field for private enterprise in the matter of scholarships, for it is open not only to Provincial Governments and Universities but also to private individuals to either grant or endow scholarships. It is also true that the danger which I have pointed out will be minimised by the decision of the Council to charge no tuition fees, and to give some remuneration, after a certain period to students who have qualified themselves to work as Demonstrators, but nevertheless the danger will exist and I feel it my duty to sound a warning note against it. I cannot help feeling that the Council will be well advised to keep an open mind on the scholarship question until they are satisfied by actual experience that scholarships are not actually needed.

I will conclude, Ladies and Gentlemen, by wishing the new Indian Institute of Science the successful future which it so richly deserves from the loftiness of its aims and the liberality of its founder.

*Indian Institute of Research and Indian University of Research were both proposed names for IISc.

For more stories about IISc’s connection to the princely state of Mysore, follow the links below: