Doctors and scientists are on a mission to understand this complex neurodegenerative disorder

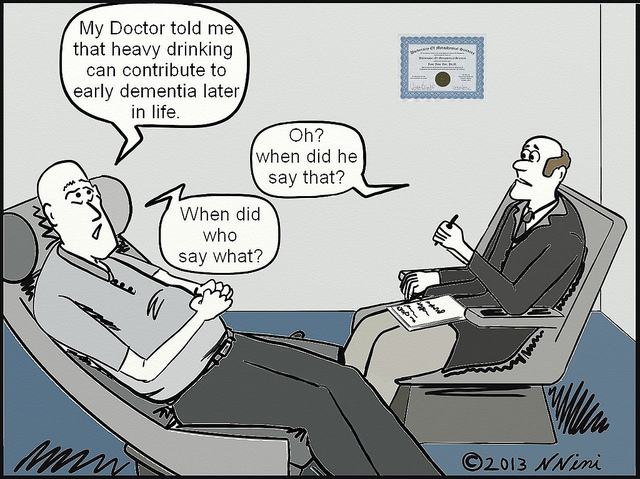

One morning, Ragini, a resident of Chennai, caught a glimpse of her 67-year-old mother, Lakshmi, using a toothbrush on her own reflection in the mirror. Ragini was taken aback by what she saw – her mother was in good mental health and sprightly for her age. “From then on, things rapidly took a turn for the worse,” says Ragini. Lakshmi was seen defecating in the open several times after that. Now diagnosed with dementia, she is supported round-the-clock by her two caretakers.

Lakshmi is among 47 million people in the world grappling with dementia, a term that is often used interchangeably with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) which is, in fact, one of the many types of dementia. “Dementia is like an umbrella term for diseases which cause a decline in cognitive ability. There are many causes. For example, consider jaundice. This could be due to the presence of a stone or hepatitis. The same applies to dementia,” clarifies Ratnavalli Ellajosyla, a neurologist at Manipal Hospital in Bangalore, who recently gave a talk on this neurodegenerative disorder at IISc.

“Dementia is like an umbrella term for diseases which cause a decline in cognitive ability. There are many causes”

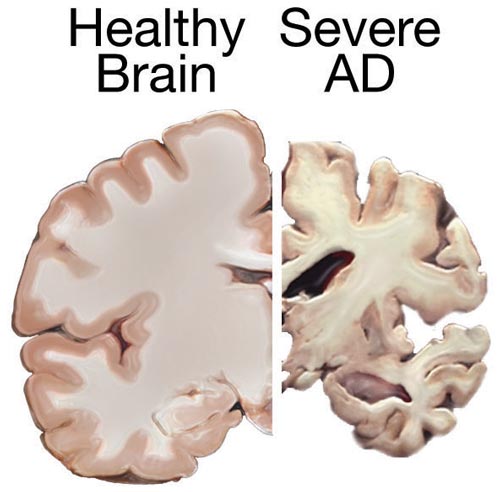

Dementia manifests itself as a deterioration in one’s cognitive skills, affecting mental faculties like the ability to recall, comprehend, calculate, learn, evaluate and so on. These symptoms result from a progressive and irreversible loss of neurons and shrinking of the brain. The most common type of dementia is AD, first reported in the early 1900s, when a woman in her fifties approached a clinical psychiatrist and neuroanatomist named Alois Alzheimer, complaining of memory loss, paranoia and sleep deprivation. He kept close tabs on her declining mental health until she died. After her death, he examined her brain and something odd caught his attention – he found abnormal depositions of protein clumps or plaques. In 1910, following the chronicling of this condition in more patients, fellow psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin named this disorder after Alzheimer in recognition of his colleague’s discovery.

Other common types of dementia include vascular dementia, characterised by reduced blood supply to the brain; frontotemporal disorders (FTD), which affect the front and sides of the brain; and Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB), commonly known as AD’s cousin, also involving abnormal protein deposition in the brain.

Ellajosyla says that while an occasional lapse in memory may not be significant, recurring episodes of forgetfulness, or bouts of disorientation – in space or time – may indicate the onset of dementia. “Any change in mood, personality also may [also] be an early sign of dementia,” she adds.

To diagnose the condition, doctors do a complete evaluation of their patients by taking into account their medical history, performance in neuropsychological tests, and brain imaging to identify any abnormalities associated with the condition. Apart from a battery of neurophysiological investigations, they also perform tests to rule out other possible causes of cognitive decline like vitamin D deficiency, diabetes, hypertension, thyroid, tumours, and stroke.

If dementia is diagnosed, doctors then attempt to determine its specific type based on the clinical evaluation and investigations. But the diagnosis of specific subtype of dementia is challenging particularly in the early stage due to the complexity of clinical presentation, says Sivakumar PT, Professor of Psychiatry at National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) in Bangalore. “For someone with diabetes, you do a blood test and can make diagnosis reliably. Diagnosis of dementia hasn’t reached that stage.”

“For someone with diabetes, you do a blood test and you know the result. Diagnosis of dementia hasn’t reached that stage”

“Research studies have shown that there is a significant proportion of individuals with dementia having discordance in the clinical and pathological diagnosis,” Sivakumar reveals while emphasising the need for more reliable tests and biomarkers to diagnose dementia and its specific type. He says that a definitive diagnosis of the specific type of dementia is often possible only after the pathological evaluation of the brain post-mortem.

However, tests to diagnose dementia are getting better. One set of tests that has been gaining ground in recent times detects biomarkers indicative of the condition. When measured from blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), these biomarkers reveal their relationship between clinical symptoms and rate of disease progression. Considerable progress has been made in identifying biomarkers for AD in CSF and molecular imaging, a relatively new innovation that helps doctors visualise cell functioning and molecular processes in the body.

Currently, CSF is widely used to measure the levels of biomarkers like β amyloid peptide and another protein called tau to diagnose AD. The search for other such protein markers is being actively pursued. On the other hand, the use of blood-based biomarkers, which can be less expensive and invasive, is still work in progress. The biggest challenge holding it back lies in detecting biomarkers from a fluid as complex as blood. Researchers, however, predict that blood-based biomarkers could be put into clinical practice in a few years from now.

Another tool commonly used is neuroimaging, which not only helps in the diagnosis of dementia, but also eliminates other causes of cognitive decline like tumour or haemorrhages. Additionally, it can provide clues about the type of dementia. Recently, amyloid-labelled PET scans have been used to indicate the levels of amyloid plaque deposition in patients with suspected AD. In the near future, given the progress in medical diagnostics, these and other tests could aid in the diagnosis of dementia in its early stages itself.

For now, though, Ellajosyla espouses the use of neuropsychological tests that assess cognitive attributes of an individual, also called culture-free tests, over biomarkers. Biomarkers which are not widely available in India are expensive and require more technical expertise while culture-free tests are relatively cheaper and can be tested on people without formal education, though a certain amount of knowledge is necessary. “All they [subjects] have to do is name things,” she says. Her findings suggest that culture-free tests may help predict the likelihood of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) progressing to AD. “Not many have looked at visual association tests which are very easy. We will explore these tests more in the future.”

Genes, environment and their complex interaction

The likelihood of developing dementia increases with age. However, understanding the root causes of this disorder is not easy, mainly because dementia, like cancer, has several types and each of them can be caused either due to genetic or environmental factors, or often, due to a complex interaction between the genotype of an individual and the environment.

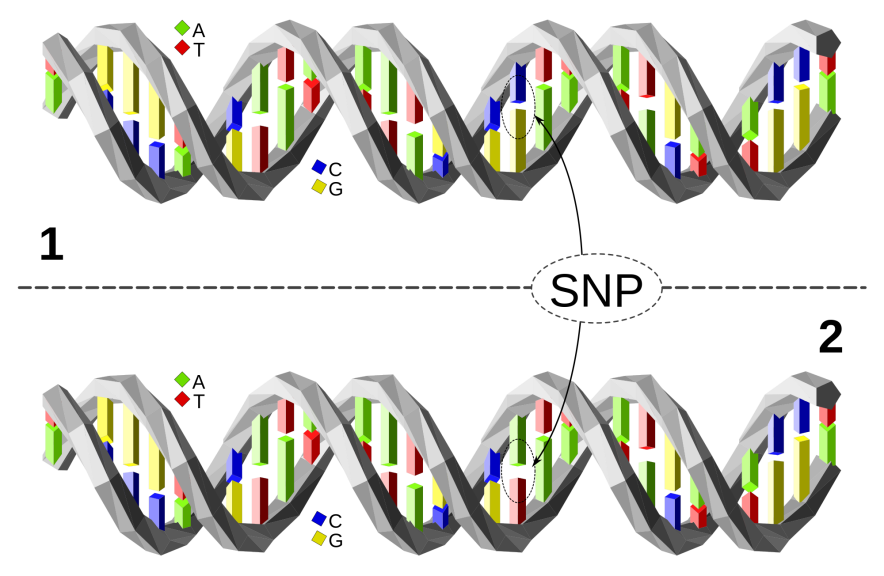

But progress has been made. Researchers have identified mutations in genes whose presence can increase the probability of developing dementia. Some of the well-known genes associated with dementia are Apolipoprotein E (ApoE), amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1 (PSEN1), and presenilin 2 (PSEN2). Researchers have also found that a genetic predisposition to dementia is more likely to trigger early-onset dementia. Because it is rare, dementia in young people can often be misdiagnosed. The three most common types of early-onset dementia are AD, vascular dementia and FTD.

In India, while the prevalence of AD is less than that in Western Europe and North America, the number of people with the disease is increasing as people live longer. However, the quality of data available on the incidence of AD and other related diseases in India is poor.

India also lags behind in research on the genetic susceptibility to dementia in its population. Recently, however, studies probing the role of genetic risk factors in Indians have been initiated by the Centre for Brain Research (CBR), which was set up in 2015 at IISc by a generous grant from the Pratiksha Trust run by Kris Goplakrishnan, co-founder of Infosys, and Sudha Gopalakrishnan. CBR is an autonomous centre of IISc focussing on clinical aspects of neurodegenerative disorders.

India also lags behind in research to understand the genetic susceptibility to dementia in its population

Ganesh Chauhan, a statistical geneticist who recently joined CBR as a scientist, scours through genes looking for genetic variations for disorders like AD and stroke. In a collaborative long-term study that is being initiated with NIMHANS in Bangalore, Chauhan and his colleagues will try to identify genes associated with dementia by comparing results between normal and affected individuals, and also hope these results might aid in designing appropriate medications.

“People usually develop [AD] at 65. But we will be studying people aged 45 years and above in a community, and monitor them for their whole life,” explains Chauhan. He believes that this will help not only understand the genetic risk factors associated with AD, but also how the disease progresses with age.

A study that CBR undertook, in collaboration with Centre for Neuroscience (CNS), IISc, investigated the frequency of ApoE polymorphisms (variations) among Indians. Previous studies which have addressed this problem showed low levels of variation in this gene. But Chauhan and his colleagues were not entirely convinced of these results. “Our results show that ApoE polymorphisms are not that low in the Indian population. Those studies might have been misreported either due to the poor sample size or use of inefficient technology,” he says.

But pinning down genes associated with a disease is a huge challenge. How does one read the entire genome of an individual which is 3 m in length and contains thousands of genes?

But pinning down genes associated with a disease is a huge challenge. How does one read the entire genome of an individual which is 3 m in length and contains thousands of genes?

In the last few years, thanks to dramatic breakthroughs in gene sequencing technologies, scientists can dive into these investigations. Today, they can carry out either Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS), which looks for common polymorphisms or Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), which reads the entire genome. Though GWAS is an economical option, it fails to detect rare polymorphisms, says Chauhan.

Besides genes, some environmental factors too have been shown to be associated with dementia. These include exposure to nitrous oxide, carbon monoxide, tobacco smoke, pesticides, consumption of alcohol, and deficiency of vitamin D.

But what scientists are discovering is that many diseases, including those that cause cognitive decline, result from a complex interaction between an individual’s genetic makeup and environmental agents that one is exposed to. For example, people with a particular variant of the APoE gene, ε4, have an increased susceptibility for faster cognitive decline. Yet, not all people with this mutation develop dementia. But why?

People with a particular variant of the APoE gene, ε4, have an increased susceptibility for faster cognitive decline. Yet, not all people with this mutation develop dementia. But why?

Many studies have shown that the environment one is exposed to and also the lifestyle one adopts affects what neurologists refer to as cognitive reserve, which is the degree of resilience to cope with brain damage. Think of cognitive reserve as a buffer which could delay the onset of symptoms of dementia or even keep them from ever developing.

Studies have shown that cognitive reserve is governed many factors. One study reported that people with less than eight years of education had 2.2 times higher risk of developing dementia than those with more education. The same study showed that people with skilled jobs were more immune to dementia.

Recent research is also shedding light on the importance of a healthy lifestyle. Cognitive reserve is higher for those who keep themselves physically and mentally active. “It is important to do physical exercise or perform yoga, engage in cognitive activities and maintain an active social engagement to keep dementia at bay,” explains Sivakumar.

“It is important to exercise or perform yoga, and maintain an active social engagement to keep dementia at bay”

The role that lifestyle factors play in stalling dementia was highlighted in a presentation made at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2017 (AAIC) in London this year. It claimed that one-third of global dementia may be preventable. A review by LANCET described the role of nine factors which increases susceptibility to dementia: low levels of education, midlife hearing loss, physical inactivity, high blood pressure (hypertension), type 2 diabetes, obesity, smoking, depression, and social isolation – as risk factors for dementia. Knowing how some of these factors interact with genetic factors could help people make informed lifestyle choices.

But a thorough understanding of the diverse and complex causes of dementia still eludes us. Many debates are yet to be resolved. For instance, some researchers have suggested that being able to speak more than one language may help delay the onset of AD. However, these results have been contradicted by a study conducted by Ellajosyla on 600 patients in her clinic. However, she adds, “We found an effect for FTD, where bilinguals had an onset eight years later compared to monolinguals, after controlling for education and severity of dementia.” “Ideally,” she explains, “we would like to do a community study and follow normal elderly people without any cognitive impairment over several years and study the contribution of diet, vascular risk factors and also education and bilingualism.”

Coping with dementia

In spite of the progress in our understanding of the causes of dementia, treatment options are dismal. Medication helps, but we have no cure for it yet. Patients with AD have low levels of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that helps in learning and memory. To treat this condition, doctors widely prescribe cholinesterase inhibitors. These drugs inhibit the action of cholinesterase, an enzyme which under normal conditions breaks down acetylcholine. Inhibiting cholinesterase protects acetylcholine from further depletion. Unfortunately, this treatment is suited only in the initial stages of dementia and may help reduce symptoms of cognitive impairment. More sophisticated approaches to stop or delay disease progression, also called disease-modifying treatments, are yet to see the light of day.

Besides cognitive decline, dementia can also lead to other psychological issues. It is not uncommon to find patients battling dementia also experiencing hallucinations and delusions. In addition to that, they may also develop changes in personality, experience dramatic mood swings, and, in some cases, become aggressive and agitated. This places a heavy burden on the family members of those suffering from dementia who often find themselves unable to cope with the situation, and are forced to rely on care centres for additional support. What Rita* went through is a case in point.

In addition to that, they may also develop changes in personality, experience dramatic mood swings, and, in some cases, become aggressive and agitated. This places a heavy burden on the family members of those suffering from dementia who often find themselves unable to cope with the situation

Rita’s father was falling sick repeatedly. As his health deteriorated, she was hoping for support from her mother, Claire*. But instead, Claire, who was showing some symptoms of dementia, became indifferent to the plight of her ailing husband, an emotional Rita recalls. Soon, her mother developed other major behavioural issues. She grew violent and began making false accusations against her family. After about six months, Rita’s father passed away. At his funeral, Claire did not show any emotions. This was a trying time for the whole family.

Rita soon realised that she couldn’t look after her mother anymore as her condition worsened and it started taking a toll on Rita’s own health. Her doctor suggested that Rita seek help for her mother from a residential care facility. Claire was taken to one such support home in Bangalore. “They did the most amazing service for six years until my mother passed away of old age. She was one of the most obstreperous residents, beating her caregivers and accusing the Director of being ‘Hitler’, but she was treated with patience, sympathy, and firmness. Counselling for families with a dementia patient is available. The support structure is extremely good,” says a grateful Rita.

*Names have been changed