The old Aerospace Engineering building at IISc represents an architectural style that blends minimalism and functionality

IISc is an institution with a history of more than 100 years. Not surprisingly, there are many stories here to be told. And not just about its people. There are also tales of its buildings waiting to be recounted.

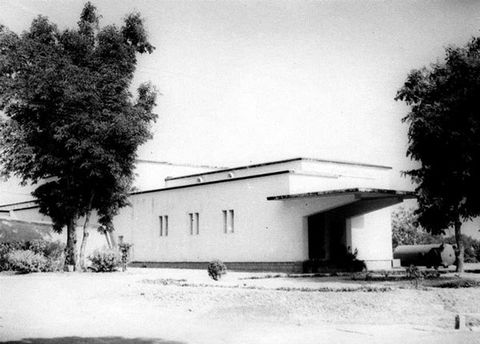

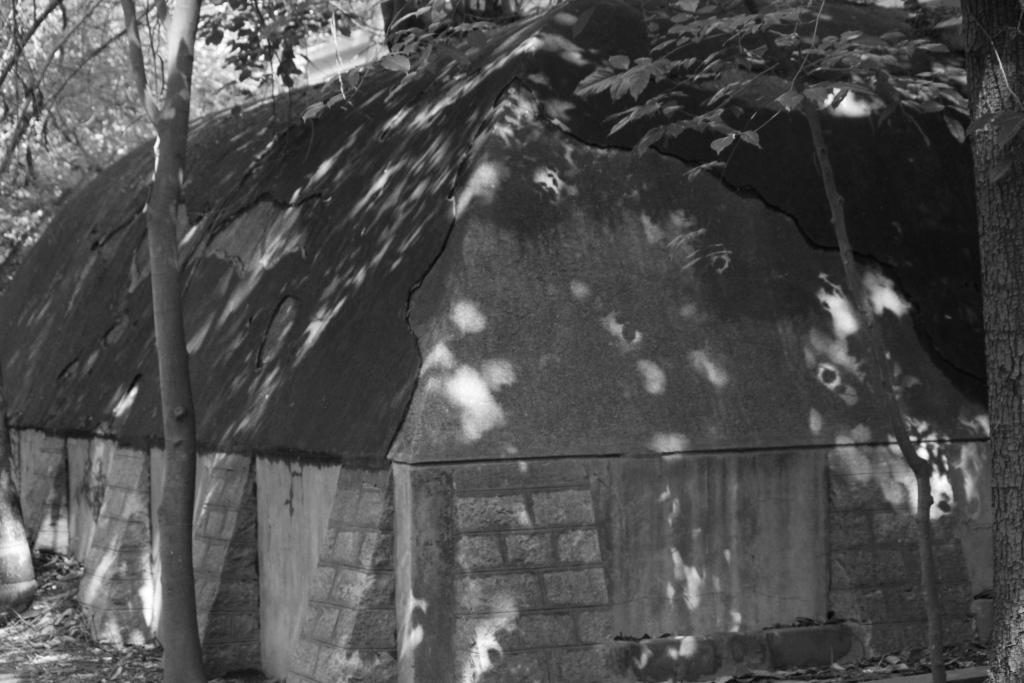

Hidden amidst the lush canopy of the Institute is one such building which until a few years ago was the home of the Department of Aerospace Engineering – called the Department of Aeronautical Engineering until 1982. The building oozes vintage charm: it has a classic entrance with the wide wooden doors, pastel tones on its walls, and a striking wing-shaped overhang sloping over the main entrance. It was designed by Otto Koenigsberger, a German refugee, living in Bangalore.

The building oozes vintage charm: it has a classic entrance with the wide wooden doors, pastel tones on its walls, and a striking wing-shaped overhang sloping over the main entrance

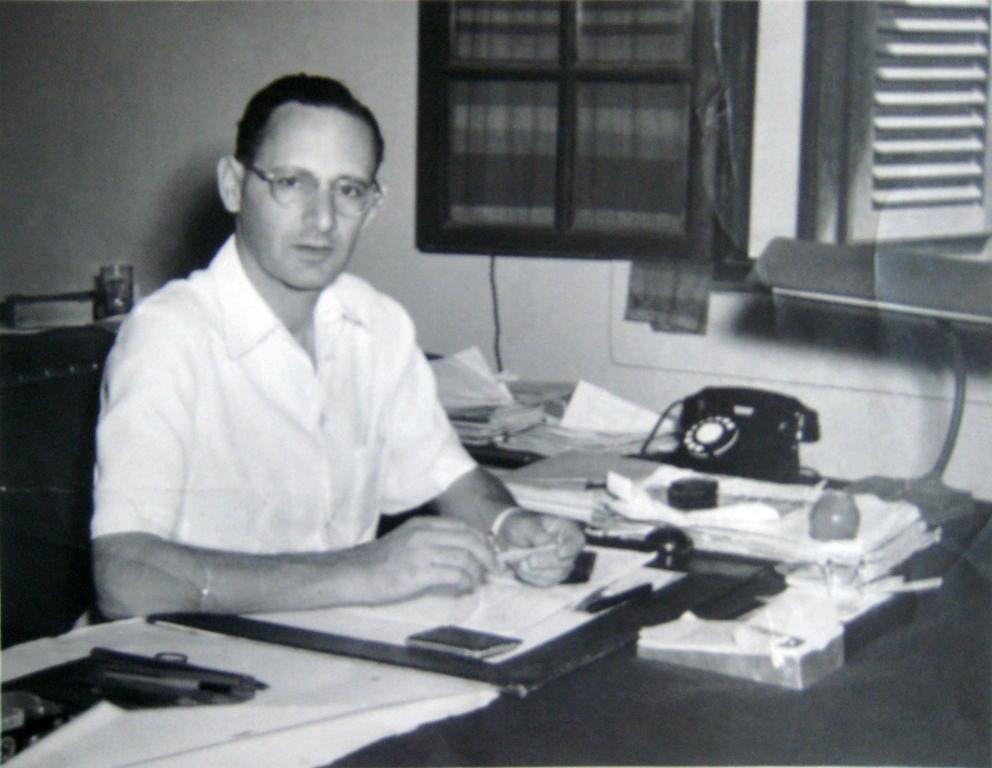

During the 1930s, thousands of Jews fled Germany after the Nazis came to power. One of them was Koenigsberger who first moved to Egypt when he lost his job in his homeland. After spending a few years studying the architecture of ancient Egyptian temples, he arrived in India to become the Chief Architect of the State of Mysore, a position he held from 1939 to 1948. He constructed many structures during this period in Bangalore: the City Bus Terminal at Kalasipalayam, the Krishna Rao Pavilion in Basavanagudi, the Bathing Ghat in Chickpet, the Tuberculosis Sanatorium on the grounds of NIMHANS, and the Victory Hall (now the Jawahar Bal Bhavan) in Cubbon Park. Koenigsberger was also a town planner. He went on to plan cities like Jamshedpur, Faridabad, Bhubaneswar and Sindri. In 1948, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru appointed Koenigsberger as India’s first Housing Director to build temporary houses for people from across the border who had become refugees as a result of India’s partition.

When Koenigsberger was in Bangalore, he became good friends with Homi J Bhabha who was then at IISc. And through Bhabha, he came into contact with the Tatas. Both Koenigsberger and the Tatas hit it off immediately. This was mainly because they shared an appreciation of the importance of using science in architecture and town planning.

Koenigsberger’s association with the Tatas resulted in him leaving behind an impressive architectural footprint in IISc. Besides the Aeronautical Engineering building, he was responsible for the Metallurgy (later renamed as Materials Engineering) building, a hydrogen gas plant (now housing commercial establishments including Prakruthi restaurant), and a dining hall and auditorium (currently serving as the Hostel Office).

The Department of Aeronautical Engineering– the first of its kind in India – was set up in 1942 with the help of VM Ghatage who was then on deputation from the recently established Hindustan Aircraft Limited, which later became Hindustan Aeronautics Limited. Koenigsberger was called upon to design the building which was to house this Department. Trained as a modern architect, he believed in what he referred to as scientific architecture. He saw no contradiction in combining local wisdom with his philosophy of modern architecture. He is described by Rachel Lee, a historian who has studied his work, as an “experimenter”. This brought him into conflict with his boss Sir Mirza Ismail, the Dewan of Mysore State, who favoured a more colonial architectural approach. But Koenigsberger persisted with his efforts to incorporate scientific principles into his designs, though he often gave into the demands of Ismail who insisted on porticos and clock towers. However, he had more freedom to express himself in the buildings he designed as a private architect, including those at IISc. The first of these was the Department of Aeronautical Engineering.

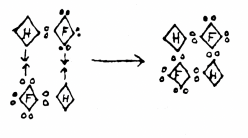

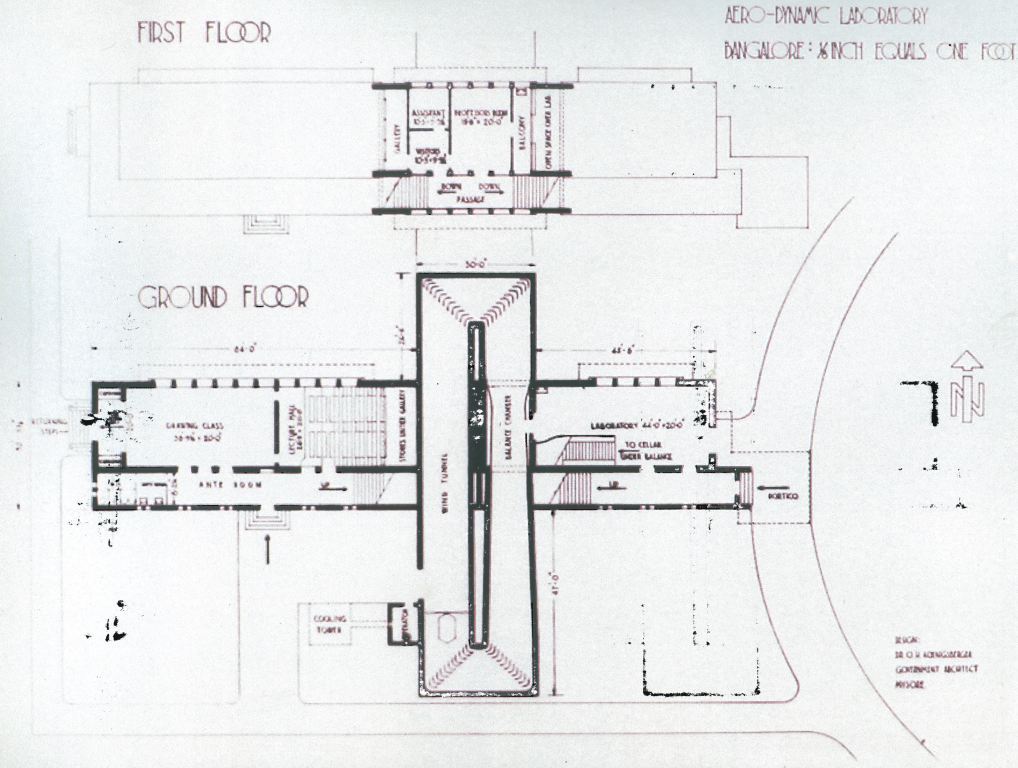

Koenigsberger designed and constructed the building in quick time. He also designed India’s first wind-tunnel which is embedded in the building (the tunnel still exists, but has not been used for many years). In 1959, an open-circuit wind tunnel was constructed, one that continues to be used to this day.

In a journal called Architecture Beyond Europe, Lee provides a vivid description of this building. She writes: “The most ambitious element of Koenigsberger’s design is undoubtedly the 30 m long elliptical low-speed closed-circuit wind tunnel. The wind tunnel loop, which has a test section of 2.2 m x 1.5 m, and a maximum wind speed of about 200 mph, was cast in concrete and partially embedded in the ground. Short granite buttresses provided additional support. Instead of covering the concrete structure, Koenigsberger, no doubt following his own aim of architectural honesty, exposed it. It was India’s first closed-circuit wind tunnel, and Koenigsberger considered its construction, in light of the limited resources and technical expertise available, a huge achievement. Indeed, at the time, the Aeronautical Engineering Department at the IISc was the only place in India where facilities existed for training and research, both theoretical and experimental in Aeronautical Engineering.”

Lee continues: “Straddling the wind tunnel is the main building of the Aeronautical Engineering Department. In contrast to the monolithic concrete wind tunnel, the Aeronautical Engineering building is built of white-painted plaster-covered bricks on top of a granite plinth. On the narrow east-facing elevation, a cantilevered porch canopy, which is somewhat reminiscent of a wing, marks the main entrance. The elongated rectangular block contains a laboratory, a lecture theatre and a drawing classroom at ground level, with offices for the professor and an assistant situated in rooms directly above the wind tunnel. Koenigsberger relies on passive techniques for ventilating the building. The south-facing access corridor protects the main spaces from solar gain and, because it is slightly lower than the main spaces, allows for ventilators to be fitted at the top of the walls in the teaching spaces. The narrow plan enables effective cross ventilation and the north-facing elevation provides natural light to the main spaces through two blocks of tall recessed window openings protected from glare and rain by thin bands of black-edged chajjas.”

“Indeed, at the time, the Aeronautical Engineering Department at the IISc was the only place in India where facilities existed for training and research, both theoretical and experimental in Aeronautical Engineering”

A few years ago, the Department moved to a new, bigger building. But the old one still stands and with it the many stories of its glorious past, including that of its association with an exiled architect who left behind a minimalist modern architectural legacy.

*Akhila Thomas is a first-year undergraduate student at Christ University where she is studying English (Honours)