Socialising in the digital age

Imagine sitting at Sarvam, basking in the bliss of a good hair day. The weather is pleasant, the sun is timid and a cool breeze is playing its part – the quintessential hyper-marketed Bengaluru weather. Around you, everyone chats happily. There is a reassuring calm within the chaos. A casual blink, flash! You find yourself in another reality; a world no one else sees but you. Panic-stricken, you look around, but any trace of companionship is gone. There is no one to speak or listen to, no one to reach out to, and no one to comfort you.

While this terrifying little thought experiment is hypothetical and may sound eerily similar to the plot of Stranger Things, the sensation of being trapped with no one else around is very real. So real, in fact, that the World Health Organisation declared “loneliness” a global health threat in 2023.

Psychology Today defines loneliness as “the distress that arises when there is a gap between the social connections we desire and those we actually experience.” Recent studies paint a troubling picture of loneliness as a Trojan Horse that quietly seeps into our modern lives. The burning question is: Why are we witnessing a surge in loneliness? What is it about loneliness that makes it such a persistent part of human experience, and how might we begin to heal from it?

At first glance, the idea seems paradoxical; some readers might even question the very premise of discussing loneliness in the 21st century. After all, isn’t everyone just a tap away on Instagram, WhatsApp, or Snapchat? And yet, experts keep reminding us that digital hyperconnectivity does not always translate into genuine human connection. In fact, adolescents, the so-called “natives” of technology and social media, are reporting some of the highest levels of loneliness in recent years. Depending on the country, estimates range from 14.4% to 33%, with numbers rocketing to nearly 50% during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For college students, the vulnerability runs especially high. Thrown suddenly from the comforts of their school life into the demanding chaos of university life, many find themselves juggling heavy workloads, navigating new social circles, and adjusting to the loss of a steady family support system – a barrage of changes that can invite a feeling of alienation and isolation. Some studies suggest that in various countries, moderate and severe loneliness is reported in 30-60% of college students.

‘Social media has built a shiny illusion of being connected ‘anytime, anywhere,’ but in reality, we’re drifting farther apart’

“I think people today are lonelier than ever before. More and more of us are slipping into the ‘reel’ world rather than being present in the real one,” feels Sreenjoy Saha, a second-year Master’s student in the Department of Microbiology and Cell Biology (MCB). “Social media has built a shiny illusion of being connected ‘anytime, anywhere,’ but in reality, we’re drifting farther apart. Even on campus, where the number of acquaintances keeps climbing, the circle of true friends feels smaller and smaller. This stings especially hard during festivals, when you are away from both friends and family.”

His words echo a sentiment that is shared by many others on campus, across disciplines. A chatter that led this scribe to wonder if this was just a passing feeling or part of a larger pattern. To unravel the truth, I conducted a mental health survey, adapted from the UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) Loneliness Scale, where participants answered questions about feeling isolated, left out, and lonely. A total of 141 students across undergraduate, Master’s, PhD, and postdoctoral programmes responded.

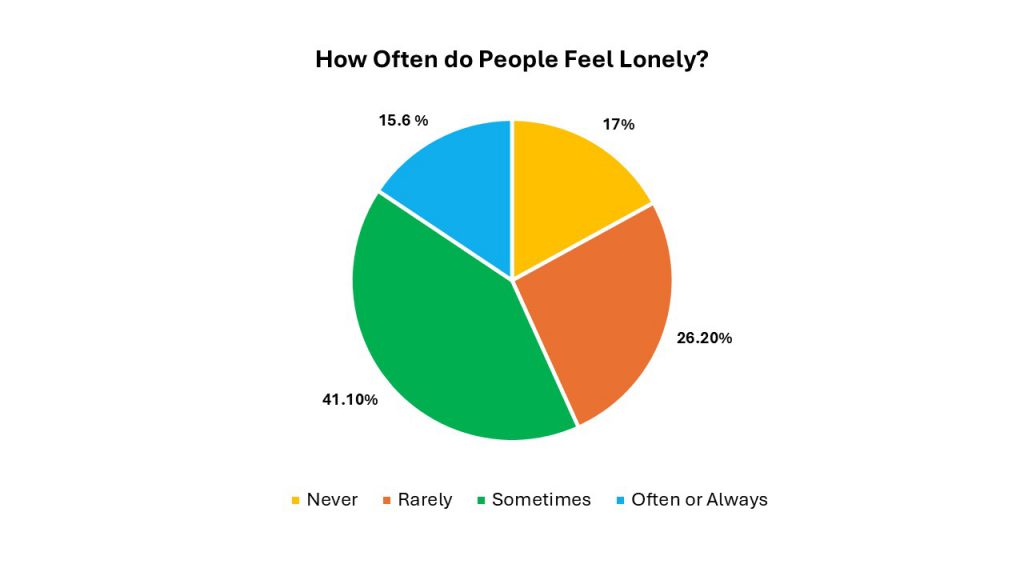

The results were sobering. Over half of all respondents (56.7%) reported ‘feeling lonely’ at least sometimes, and about one in six (15.6%) said they often or always felt lonely. The sense of disconnection ran deeper still, with 57.4% admitting to feeling left out, and 58.1% feeling that they lacked companionship.

When it came to friendships, 8.5% admitted to having no close friends on campus. The effect of loneliness was also gendered – female students (61.6%) were affected more often than males (53.3%). Respondents in relationships were considerably less likely to feel lonely (41.5%), compared to those who were single (63.3%).

Results of a survey amongst 141 IISc students conducted by the author, showing that 56.7% of respondents reported feeling lonely at least sometimes, highlighting the widespread and often unspoken nature of social isolation (Image: Divyanshu Bhatt)

These numbers and percentages paint loneliness as a very real picture on the canvas of student life. But prevalence doesn’t always suggest harm. Some traditionalists and naysayers can easily dismiss this as just another “generational construct.” After all, the earliest mentions of the word loneliness date back to the late 16th century. And even in the 18th century, the newly industrialised society did not see loneliness as a dire concern. So, is loneliness just another “modern problem” that the younger generation claims to suffer from?

As it turns out, biology addresses this concern. A plethora of studies reveal that social pain, because of exclusion or loneliness, activates brain regions that are involved in physical pain, such as the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. The cost doesn’t stop there; loneliness is also linked to faster cognitive decline, poorer mental and physical health, greater risk of cardiovascular disease and dementia, and a higher risk of mortality.

So, biologically at least, loneliness isn’t just in our heads; it is part of how we are wired. This begs the question: Why would evolution preserve such a need for companionship and make its absence hurt so much?

The answer lies in our social roots. Humans didn’t evolve to survive alone; our ancestors thrived in groups; survival of the community often meant survival of the individual. To keep these bonds strong, our brain developed ways to make us crave connection. The Evolutionary Theory of Loneliness explains it simply: loneliness is like a signal, warning us when our social bonds are at risk. Just as physical pain motivates behaviours to protect the body, loneliness motivates behaviours that protect our social self from isolation and exclusion.

While loneliness may have originally evolved as a survival mechanism, it has morphed into a pressing concern in modern life

While loneliness may have originally evolved as a survival mechanism, it has morphed into a pressing concern in modern life, thanks, in part, to highly fragmented social structures. People leave homes, crossing borders and oceans in search of better opportunities, leaving behind, even if only temporarily, their support system of family and friends.

“Certainly, with rising individualism, our brains are facing a mismatch. Designed for living in close-knit groups and interacting frequently, we now find ourselves in fragmented communities that our minds were never built for,” says BG Shridhar, Clinical Psychologist at the IISc Wellness Centre. “The outcome is isolation, visible even in IISc hostels, where students often don’t know their own neighbours. Apart from this, another factor that dictates people’s vulnerability to loneliness is the coping mechanisms they have come up with to deal with solitude.”

Whether loneliness becomes a fleeting feeling or a persistent shadow often depends on individual personalities and the art of dealing with the stresses of modern social life.

“How modern society’s structure has impacted loneliness is complex and multifaceted,” says Peter J Richerson, a renowned biologist and distinguished Professor Emeritus at University of California Davis.

“Ancestral societies were highly variable but generally small and intimate. I imagine that people with weak skills at forming social ties can become very lonely in the modern world, whereas in traditional societies, they would have been more or less forced to interact with family and local community members. In modern large scale societies, extroverts and those open to new experiences can build large circles of friends and mostly thrive. Introverts perhaps tend to get lost.”

An interesting revelation from students was their view of social media, not as a lifeline keeping humanity connected – as I had expected – but as a house of cards against loneliness.

The popular consensus was that while texts and calls may be soothing in the moment, they cannot replace the warmth and reassurance of physical presence. Research backs up this idea as well. The richest social bonds are formed by in-person interactions, while superficial or passive contact, such as brief chats or social media likes, has little impact on loneliness and can even deepen it. What’s more, studies consistently report a bidirectional link between social media use and loneliness – those who feel lonelier tend to use social media more, and heavier use often feeds further loneliness, like a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Now that Pandora’s box has been opened, the natural question is, what can we do to feel less lonely and a little happier? As is often the case, the problem itself hints at the solution. Although loneliness is often thrown around as a “one-size-fits-all” term, it has layers. For instance, it is not the same as social isolation – the objective state of having little or no contact with others. Loneliness, instead, is a subjective phenomenon that arises when there’s a discrepancy between the social connections one has and those that one desires.

“Although many students are surrounded by friends, they often experience a sense of loneliness due to the absence of emotional support and a genuine sense of belonging. The quality and emotional depth of friendships play a great role in overall well-being”, says Sayeda Tamanna Yasmin, Psychiatric Social Worker at the IISc Wellness Centre.

Because loneliness is so deeply personal, any solution must aim not only at increasing social connection but also improving one’s perception of said connection. Practically, this means reaching out, sharing one’s feelings, and being vulnerable with the right people. Simple shared experiences like open-for-all game nights, movie outings, coordinated lab breaks or planned meals can go a long way in boosting emotional well-being.

An example of community building in action: IISc students on a trek to Ramdevara, Karnataka, coming together, forming bonds, and building camaraderie (Photo courtesy: Yogesh/@pixelsbyyogesh)

Even small gestures, like checking in on classmates or chatting briefly with someone you know, can create meaningful bonds. And yes, it also means being open to trying out new experiences with strangers, even if the idea sounds nerve-wracking.

“When it comes to loneliness, the first step toward healing is understanding where it really comes from – being over-absorbed in work, one-sided friendships, or not having meaningful connections at all,” remarks Shalini John, Consultant Clinical Psychologist based in New Delhi. “The truth is, no single remedy fits everyone. Simply ‘making more friends’ doesn’t always help. Sometimes, it requires a quiet moment of reflection – Are your friendships mutual? Have they weathered ups and downs?”

‘A golden rule that I always recommend is to talk to at least three people who are close to you every day’

According to Shalini, a useful way institutions can contribute towards this is by encouraging fun-based and non-competitive group activities, like academic projects or collaborations or even informal get-togethers.

“These teach people how to navigate group dynamics, understand each other, and discover what makes them feel seen and valued,” Shalini explains, while adding that therapy also helps, as it enables people to open up to others.

“A golden rule that I always recommend is to talk to at least three people who are close to you every day. Simply talking helps a lot,” says Adarsh B, Consulting Psychiatrist at the IISc Wellness Centre.

At the same time, managing loneliness also means cultivating realistic expectations and looking inward. Caught in the whirlwind of work and hustle for the next “good thing”, we often forget to check in with ourselves. What do we want from friendships? Do we have people who will genuinely celebrate our happiness? If not, do we want someone like that in our lives?

To that end, maybe the first step toward connection is honesty – with others, yes – but also with ourselves.

In the age of constant motion, where something or the other is always going on – work, social media, endless entertainment, incendiary news – we rarely pause and reflect on our social bonds. Yet, regardless of whether we like it or not, our brains are wired to survive in a social world, and no matter how much we distract ourselves, at the end of the day, we can’t escape millions of years of evolution.

Not yet, anyway.

Divyanshu Bhatt is a Master’s student at the Centre for Neuroscience, IISc, and a science writing intern at the Office of Communications

(Edited by Sandeep Menon)