How Alfred Gibbs Bourne became IISc’s second Director

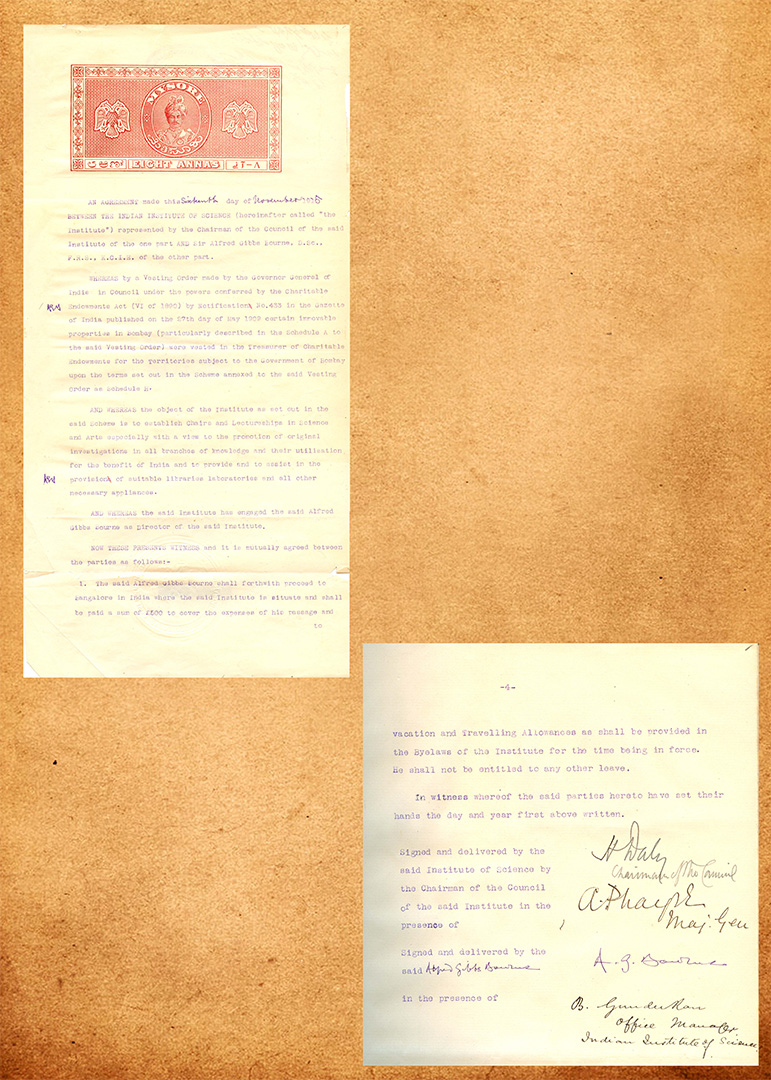

After overseeing the construction of several early buildings at the Institute and laying the groundwork for its growth, Morris Travers stepped down as IISc’s first Director in 1914. What followed was a year-long hunt for the person to fill this role. Members of the IISc Council wanted to provide adequate laboratories for the applied chemistry department and increase equipment for other departments. The Council consisted of a mix of British officers like Hugh Daly, professors like Alfred Hay, Alfred Chatterton, JJ Sudborough, WF Smeeth, and Indians like M Visvesvaraya (the then Dewan of Mysore), HJ Bhabha, Dorabji Tata, and JD Ghandy, the Tatas’ solicitor.

According to IISc’s 1914-15 Annual Report, the Council decided against asking the colonial government for funds because of the ongoing World War I and made do with the resources at their disposal. However, these resources were not enough and so the Council decided to combine the offices of the Director and Professor of Applied Chemistry. They appointed a special committee in England to look for suitable candidates who would simultaneously assume both roles.

The members of the Council were divided in their opinions, which led to internal squabbles. Dorabji Tata wanted IISc to pursue pure science research, which would not yield immediate results. Visvesvaraya, on the other hand, wanted the Institute to become primarily a technical school that would train students for a few years and only then select some of them for research. Then there was Alfred Chatterton, a chemistry professor at the Institute who strongly objected to recruiting a new Director as had his eyes on the role.

The deliberations went on for months. Finally, the special committee recommended Robert H Pickard, a principal at Blackburn Technical School in Lancashire county, England. However, in a meeting held on 31 May 1915, the IISc Council rejected Pickard, ostensibly because he didn’t have the right background they were looking for. Frustrated, the Council decided to invite one among the special committee to take up the Directorship. That person was Alfred Gibbs Bourne, a zoologist and plant enthusiast.

Before coming to IISc, Bourne had amassed considerable experience in administration while also pursuing his research in invertebrate morphology.

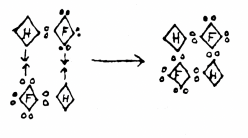

Bourne was born on 8 August 1859 in a small coastal town in England called Lowestoft. His father, also called Alfred Bourne, was the principal of the Stockwell teacher-training college. In 1876, the young Bourne joined University College School in London to pursue his Bachelor’s degree. Like his contemporaries, he was influenced by the work of Edwin Ray Lankester – a celebrated invertebrate zoologist who was the Jodrell Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy at the same college. Gradually, Bourne became Lankester’s assistant and then junior colleague. In an obituary of Bourne, published by The Royal Society, zoologist John Stanley Gardiner writes that Lankester was impressed with Bourne’s extraordinary resourcefulness when it came to designing lab equipment and keeping them in working order. Bourne fabricated large aquarium tanks in the lab in which he would collect and observe various animals to study their morphology.

Bourne fabricated large aquarium tanks in the lab in which he would collect and observe various animals

The papers that Bourne published with Lankester included accounts of molluscs like the pearly nautilus, and the anatomy of horseshoe crab eyes, scorpions and earthworms. In 1880, he published a detailed study of the nephridia – rudimentary kidneys – present in medicinal leeches. This, paired with Lankester’s histological studies of the same organ and the circulatory system, created great interest among the science community. He was given the rank of assistant professor of zoology and awarded a DSc degree from the University of London. Bourne also published detailed papers on the anatomy of leeches – a study that lasted five years till 1885.

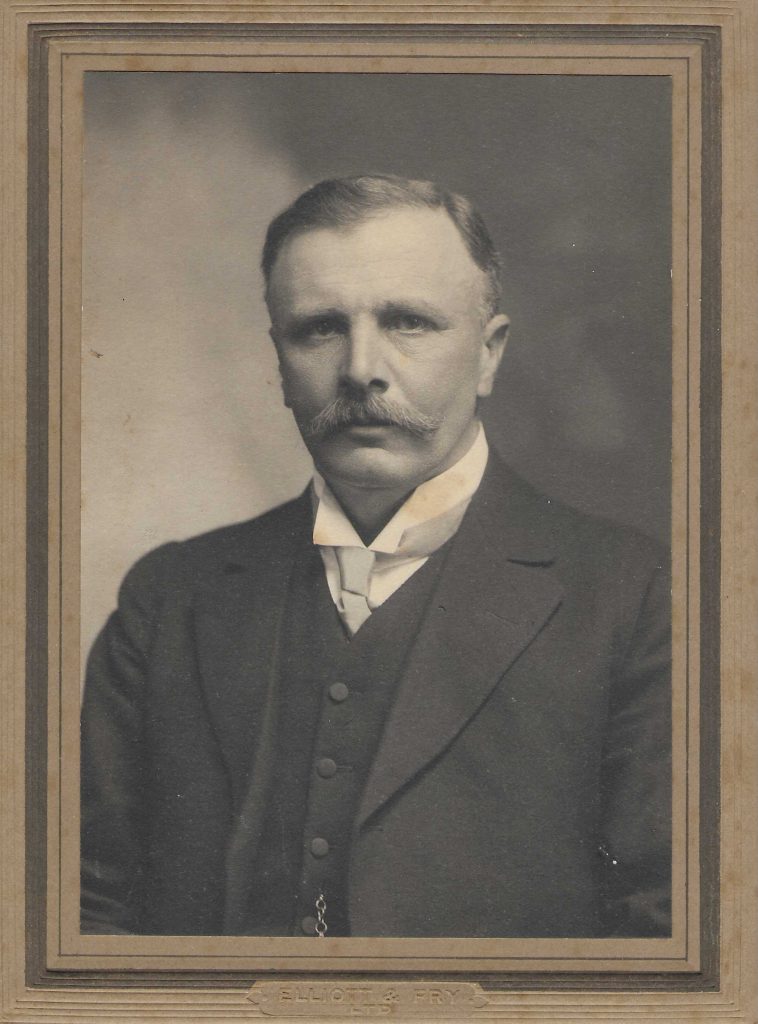

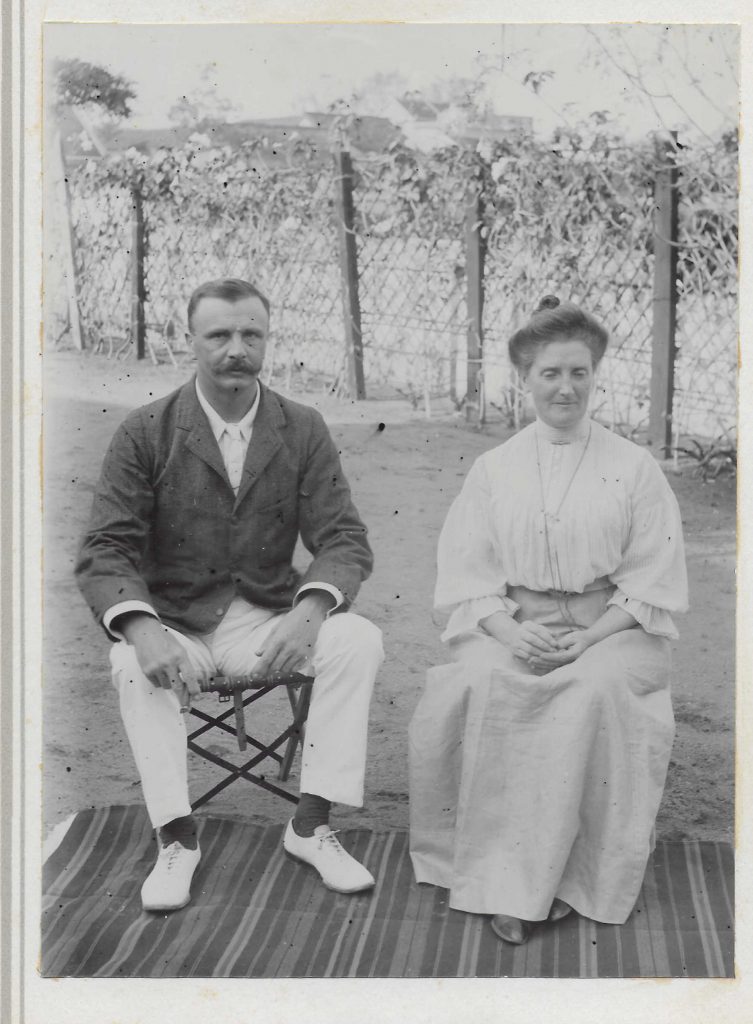

“I inherited from my grandfather – who was the grandson of Alfred Gibbs Bourne – a Burmese chest full of photographs and documents, mostly personal items related to Alfred Gibbs Bourne and his wife Emily Tree Bourne,” says Mark Bourne-Worster, a senior advisor at the UK Environment Agency. Among the collection are copies of letters exchanged between Bourne and his wife before their marriage, correspondence the Bournes received over the years, botanical paintings by Emily, and a biography put together by Mark’s grandfather titled A History of the Bourne

Family 1577 to mid-20th Century. Mark explains that once Bourne finished his doctoral degree, he was looking for a job and had applied to two positions. One was the curator of the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, and the other was a Professor of Biology at the newly established University of Auckland in New Zealand. In the meantime, Mark says, Randolph Churchill, secretary of state for India, approached Lankester asking him to recommend someone for a professorial post in Madras. Lankester recommended Bourne.

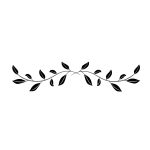

In 1886, Bourne was appointed as the chair of the biology department at Presidency College, Madras. Apart from teaching, he also made time for research. He borrowed an artificial lake tank on the college grounds to carry out his experiments. He studied earthworms, fishes and amoebae found in sediments at the bottom of freshwater ponds. In 1889, he visited Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to study different species of earthworms and published a detailed study – his wife, Emily, made intricate drawings of the worm for this paper.

In 1886, Bourne was appointed as the chair of the biology department at Presidency College, Madras. Apart from teaching, he also made time for research. He borrowed an artificial lake tank on the college grounds to carry out his experiments. He studied earthworms, fishes and amoebae found in sediments at the bottom of freshwater ponds. In 1889, he visited Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to study different species of earthworms and published a detailed study – his wife, Emily, made intricate drawings of the worm for this paper.

As the years passed, Bourne had to take on more administrative duties, which meant that his research took a backseat. He was appointed as the Registrar of the University of Madras and later Principal of Presidency College. Gardiner refers in the obituary to Bourne’s “successful organisation of games as a definite part of the college’s activities, a development of immense psychological importance to the students and later adopted in every similar institute in India.”

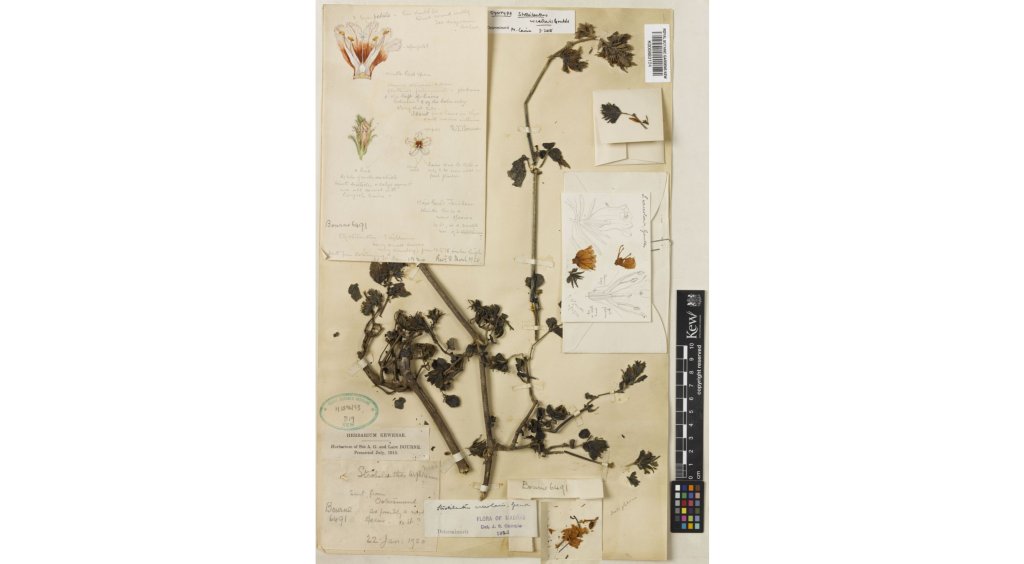

Bourne and Emily also nurtured a love for local flora and collecting botanical specimens. Keen to carry out a thorough botanical survey of the Madras presidency, Bourne offered his services as a botanist for the Madras government from 1897 to 1898. Apart from Madras, he also visited Palani Hills, Nilgiri Hills, Godavari, Coorg and Nilambur, scouting for specimens.

In 1903, Bourne became the Director of Public Instruction and Commissioner for Government Examinations. He implemented wide-scale educational reforms that were replicated throughout the country. Gardiner explains that the university matriculation exams provided little indication to the employers about how qualified the candidates were. Bourne fixed the problem by coming up with a ‘completed school certificate’ that gave a snapshot of the student’s educational background.

Even after his term as government botanist ended, Bourne and his wife continued travelling and scouting for different plant species, collecting and carefully preserving hundreds of specimens. Emily would write frequently to David Prain, the then Director of the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens in London, asking him to verify the identity of the specimens she and her husband ‘Fred’ collected. In one of the letters sent in 1908 – now in the archives of the Kew Gardens – she thanks Prain for helping to identify all the “scraps of plants” she had sent to him. She also highlights a memorable week spent in Bangalore after some ‘jungley’ touring, before starting on another 3-4 week trip in the district of Bellary. “The monsoon is behaving badly this year – the rainfall is so poor everywhere; there is much crying for water,” she writes.

Bourne and his wife continued travelling and scouting for different plant species, collecting hundreds of specimens

The Bournes kept in touch with Prain and took the help of Philip Furley Fyson – who succeeded Bourne as professor of biology at Presidency College – to preserve, pack and ship off their entire collection of herbaria samples to Kew Gardens, where they are found to this day. The Bournes also wanted to publish a detailed review of the specimens they collected, especially grasses, for which they sought out many European herbaria. But these plans were put on hold when Bourne was called to head IISc.

Dorabji Tata, in a lengthy letter to CHA Hill, a government official, gave an account of the events that led to selecting Bourne as the next Director of IISc. He wrote that the Council rejected Pickard for two reasons. One was that two other professors, Alfred Hay and JJ Sudborough, considered themselves senior to Pickard and did not want a junior above them. The other was that many wanted Alfred Chatterton to be selected as the next Director. “This has been in the air since Travers retired,” Tata wrote. This was probably also why the Council’s sub-committee (of which Chatterton was a member) stressed that they should find a man with a “large Indian experience and working knowledge of some Indian industries.” Tata deduced that Chatterton’s vested interest was why the pay was bumped up from Rs 2,200 to Rs 3,000, as Chatterton was getting paid the latter amount in his temporary position with the Mysore darbar. “So if Chatterton could be transferred on the same pay to the Institute, it would be a good thing for everybody concerned – except the Institute; but nobody cares about that.”

Tata wrote that under no circumstances would he accept Chatterton’s nomination, a strong view that he also expressed to Hugh Daly, the Chair of the IISc’s Council. After a lot of back and forth, the Council decided to split the Director and head of Applied Chemistry roles, and Daly suggested that Bourne be asked to take up the Directorship without any professorial duties. “I did not raise any objection, as I felt that by accepting Bourne, I was effectually blocking Chatterton,” Tata wrote.

Bourne, who had retired from his government duties and gone back to England in 1914, initially declined the offer, urging the Council to choose Pickard. Daly privately wrote to Bourne again and requested him to reconsider. In a memo to Henry Sharp, the Joint Secretary to the Government of India in the education department, Daly writes, “He [Bourne] replied that he would reconsider and I subsequently received letters which, while expressing willingness to come out, showed that he was doing this as a matter of duty in the interests of the Institute.”

According to Daly, Bourne pointed out that he would be “put to considerable expense in getting rid of his house etc., and that his pension would be reduced if paid in India.” Bourne asked for a lump sum of 500 pounds which would also cover his trip to India. The IISc Council unanimously agreed to this in a meeting held on 5 July 1915. While the Tata brothers heavily favoured Bourne, they also wanted the procedures for appointing a new Director to be done by the book. By then, Daly received another cable from Bourne on 31 August 1915: “Sailing eighteenth September. Later steamers full. Please expedite confirmation.”

In the biography written by Mark’s grandfather, a relative recounts the time when they joined Bourne during a visit to IISc in 1915. “We spent one morning inspecting a machine that turned liquid sewage into dry manure which can then be packed and dispatched to any area – one of the latest inventions and a far cry from the basic methods,” the relative’s letter to their family reads.

A couple of months after Bourne came to IISc, Gilbert Fowler was selected as a professor in the Department of Applied Chemistry. This was during World War I, at a time when Indian research was leaning heavily towards utilitarianism. The Institute was making strides in developing explosives like acetone, using oil from mahua trees for medicines, and extracting and distilling sandalwood oil.

Despite his skill and experience at building equipment, Bourne was equally firm in his support for pure science research. Nowhere is this more evident than in the presidential speech he gave at the fourth Indian Science Congress meeting held in 1917. He laments about how the word ‘research’ had been trivialised to a perfectly simple operation, and how newspapers spoke of it in “the lightest manner,” whereas during his student days, the word was spoken “with almost bated breath”. He fondly recalled his own excitement over his early research on unravelling the complex structure of the nephridia of leeches.

Despite his skill and experience at building equipment, Bourne was equally firm in his support for pure science research

Bourne retired from the Institute in 1921, returned to England and settled in Dartmouth, where he immersed himself in his hobbies. He was adept in mechanical work and designing tiny little devices. Mark shares an account written by Bourne’s granddaughter recalling her summers at Dartmouth. She wrote about the demonstrations given by Bourne on the working of machines like the Newcomen steam engine, of which Bourne had made a scale model. He later coached her to “play with the lathes … also the clockmaker’s little treadle, and [work on the] beating of copper, the carpentry and joinery.”

Her recollection continued, “The workshop was home to many clocks, some made by Alfred. Hardly any had any hands – it was the movements that were of interest. Later, it housed all the latest models of the wireless world and record players. Sometimes only on trial from the Dartmouth shop … Bourne was deeply involved, because of his hobbies, with all of the Dartmouth tradesmen and shopkeepers. Every day he walked down in his super jaunty way, with a cap, twirling his walking stick, to discuss the latest product or matter of interest.”

Bourne was appointed the mayor of Dartmouth in 1933. In 1940, he succumbed to cancer at 81. According to an obituary in the August 1940 issue of Current Science, Bourne enjoyed a great reputation both as a teacher and as an investigator. The obituary says: “Sir Alfred Bourne may not have come into personal contact with a very large body of students in South India. Nevertheless, the few that came under his direct influence will remember the many excellent qualities of that brilliant scientist who commanded a raging popularity and widespread esteem.”