From assisting Prof Madhav Gadgil in his field work, to retiring as the librarian of the Division of Biological Sciences, Yashwant Kanade looks back at almost four decades with IISc

(Photo courtesy: Yashwant Kanade)

I was born on 16 January, 1962 in Sirsi, Uttara Kannada. After finishing primary school, even though there was a private school near my house, I joined a government school as I was interested in the NCC. I cycled a lot during my school days. When I was in the 8th standard, I cycled from Sirsi to Honnavar, almost 100 km, just to see the sea!

I took up PCMG (Physics Chemistry Math Geology) for my PUC, but didn’t get very high marks, and joined a diploma course in electrical engineering in 1982. One day, a notice on our college board mentioned that Prof Madhav Gadgil, Padma Shri awardee, was giving a talk on environmental sciences, and that anyone interested could attend. His talk was very interesting, but we were scared to go and talk to such an eminent person.

At that time, employment opportunities in Sirsi were very few. After finishing the diploma in 1983, I went to Bombay to try to get a job in Crompton and Greaves. But I didn’t like the pace of life there. It was always rushed and there was a lot of stress. I came back to Sirsi and joined a BA programme in sociology, history and economics.

While I was in Bombay, Prof Gadgil came back to our college to recruit field staff for a research station that he was planning to set up in Sirsi. My father was an attender in the college at that time, and he told Gadgil, “I have a son who has a diploma in electrical engineering.”

Around the same time, one of my cousins met Prof MS Hedge from the Solid State and Structural Chemistry Unit at IISc on a bus from Bangalore to Sirsi, who mentioned a “Tata Institute.” Until then, we had no idea that it was a science institute – we used to think that it was a tyre company connected to Tata Motors!

A couple of months after I came back from Bombay, I went to a village called Yadahalli to attend an NSS camp. There was a Technology and Development Centre (TDC) nearby where Prof MS Hedge was attending a workshop, and I went to meet him. Prof Madhav Gadgil, Prof CJ Saldanha, Prof DK Subramaniam and Prof Govindaraju had also come there to conduct workshops. There was a workshop on electrical wiring which I joined. I had a lot of curiosity, and this time, I asked some questions and they noticed me. I approached Prof Gadgil and asked him if there were any opportunities at the Tata Institute. He enquired about my background, and asked me to put in an application.

There were 10-12 people on the interview panel, including Prof LT Sharma, Principal of MM Arts and Science College; Prof RS Hegde, Yadahalli College principal; Prof Madhav Gadgil; Prof DK Subramaniam; Prof Narendra Prasad; Prof Govindaraju and Prof R Gadagkar, who had just joined. They asked me if I could ride a bicycle and what salary I expected if I got selected. I had been earning Rs 500 per month in Bombay, but did not have the courage to ask for the same amount. So, I told them that I will work for Rs 400 per month. They agreed, and told me to wait for the offer letter from Bangalore, and contact Narendra Prasad at the Sirsi field station.

My house was on the lane between Samrat Hotel where all the field staff took their meals, and the field station, which was in a rented building in Sahyadri colony. Ten to fifteen days passed and there was no letter. It became a ritual for me to stand outside my gate and ask Prasad when he passed by: “Namaste sir, why hasn’t the letter come yet?” And for him to reply: “Wait maadi, it will come.” And indeed, it did come, at the end of October. I was 21 years old at that time.

On the 2nd of November 1983, I reported to the field station. Some of the staff there discouraged me from joining. They said it was too much work. “You’ll have to go to the forest, the salary is poor, you’ll have to cycle all around,” and so on. But none of this was a deterrent for me, and so I joined as a field assistant on a project with Prof CJ Saldanha, renowned botanist and author of the Flora of Karnataka.

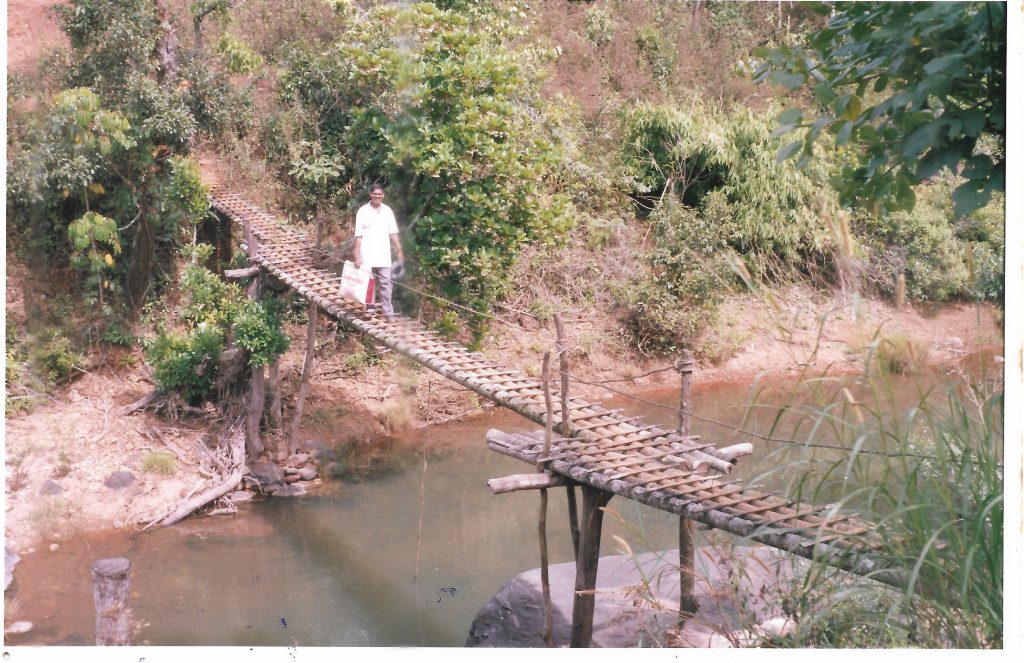

Field assistant days

DK Subramaniam and Govindaraju were part of the research team working on a proposed microhydel project on the Bedthi river. My job was to measure the water flow using a current meter. I had to collect readings at fixed times throughout the year, even in the heavy monsoon rains, and they gave me an umbrella. I had to cycle 30-35 km every day. Ultimately, the project was shelved as there was a lot of pushback from the local community, since some areas could get submerged by the project, including farms and plantations.

After that, I was put on a team collecting data on plant diversity. This involved taking measurements of the annual growth of trees, canopy cover and so on. Ranjit Daniels was working on birds at that time, and I was really interested in birds. I would spend a lot of time talking to him. Soon after, Putta Marullaiah, a botanist from Bangalore University had joined as a lab assistant. He was an expert at identifying species, and with his guidance, I learnt to identify some 50-60 species using the Flora of Karnataka identification key.

After working on the project on plant diversity, I assisted Prof BK Mishra as a translator and helped him conduct interviews in Kannada for an eco-development project. Prof Gadgil observed that I was good at translating, using technology and convincing people. One day, he asked me, “Kanade, would you be interested in handling an individual project?” I wasn’t very confident, but he gave me a project titled ‘The Economic Uses of Plant Materials’, and we created a format for data collection. At that time, I was helping out Silanjan Bhattacharya, a student working on a human ecology project. After conducting interviews for his project, I would ask the same people my own set of questions on the uses of plant materials. Prof Gadgil discussed the data I had collected and also showed me the analysis he did. He even mentioned my contribution in the journal publication.

Then I worked on a plant phenology project with Prof DM Bhat. I was a co-author on that paper. I had no idea about any of these papers at that time; they were giving me a salary and I was working.

The shift to Bangalore

In the meantime, I finished my BA and started an MA in sociology through a distance learning course from the Karnataka University, Dharwad. Field work took up a lot of my time and was tiring, especially the travel, and it was getting a bit difficult to manage it along with my studies. They told me to obtain a two-wheeler driving license. I gave up the bicycle and started riding a motorbike to the field. I remember one incident vividly. The year was 1989 or 1990. I had to collect data from Bangane Morse, a remote village in Uttara Kannada. I had to park the bike and cross a large stream on foot to reach there. This stream was in spate by the time I finished my work, and the villagers advised me to stay back. I was able to cross over the next day. But the bike refused to start, and I realised that someone had cut the accelerator cable, possibly while trying to steal it. It was getting dark and the main road was 4-5 km away. By the time I reached it, I was very tired and lay down for a bit. When I woke up, it was pitch dark, and I had no clue which direction to go. After walking for 2-3 km, I saw a light from a house. I could not walk up to their door as they had dug a trench all around to protect their land from wild animals. So I shouted for help. Fortunately, they heard me and came to get me. They gave me food and shelter for the night, and the next day I went to Kumta in a bus, and came back with a mechanic who repaired the bike.

I often had to spend some days in Bangalore, bringing specimens and other samples from the projects, and I requested them to let me stay back there, so that I could focus on my studies. Prof Gadgil agreed immediately. In November 1990, Prof Gadgil and Dr TV Ramachandra introduced me to Vijayalakshmi, who was in charge of the library at the new Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES). They said, “He is Mr Kanade from Sirsi. Please give him the charge of the library, he will run it in the future.” I said, “Sir, I don’t know anything about libraries, except when I would sign up for books from my college library.” “You can do it, I know your capacity,” Gadgil replied. I joined CES on 8 January 1985 as a permanent staff member.

Vijayalakshmi gave me an orientation, but nothing was going into my head. I started taking notes in my own language in a small notebook. I studied all the files about budget, purchase orders and so on, and continued to take notes. In six months, I became well-versed with the system and my notes became a technical report about the Library and Information Centre at CES!

I completed a Bachelor’s in Library Science from IGNOU by attending weekend classes, and also went on to obtain an MLibSc.

One day, Gadgil asked me, “Kanade, why don’t you study library science?” I quit my MA degree, and entered the world of information sciences. I completed a Bachelor’s in Library Science from IGNOU by attending weekend classes, and also went on to obtain an MLibSc. However, my official designation remained ‘Gestetner operator’ (Cyclostyle machine operator).

I registered for a PhD at Bangalore University with Prof TD Kemparaju, but was not sure that it was the right pursuit for me. I had to submit a synopsis (thesis proposal) and started writing one on ‘The Information Seeking Behaviour of Ecologists’. Around the same time, Prof Gadgil wrote a letter to the main library seeking to send me for training there. NM Malwad, the Chief Librarian, agreed. This was 1992-93. Every day, I spent an hour in the main library, observing all the activities in all the different sections so that we could implement them in the CES library. I learnt how to place orders, got international contacts for books and journals, subscriptions, got introduced to international publishers, and more. My communication skills and knowledge both increased greatly. Dr KS Chudamani, Deputy Librarian, taught me about administration, and BC Sandhya about classification of library resources. There was also Dr Shyam Prasad Pujari, who was the librarian at the Karnataka State Council for Science and Technology. He would come to the CES library on Saturdays and guide me in classification. It was not too different from the plant classification I had learnt during my days as a field assistant!

In 1999-2000, someone from the Institute told us employees that there were plots of land available in Nelamangala, so I booked one. Kaalappa, the secretary of the Employees Association at that time, also visited the site, saw that the documentation was sound, and spread the word. After that, 200 sites were purchased by people from IISc. Soon after that, when Ratan Tata visited IISc, Kaalappa requested him for financial assistance for the employees. He donated 50 lakhs, and each of us got Rs 35,000. I took a loan of 3.5 lakhs from Allahabad Bank to build a house there. This was a huge amount, and I was under a lot of pressure. In the meantime, Bangalore University sent several reminders about submitting the PhD synopsis, but I had to focus on the land and the construction. Even though I had prepared the proposal, I could not submit it on time, and I had to drop the idea of pursuing a PhD. Later, I published it as a conference paper with Chudamani.

New technologies and trainings

In 1996, I attended a conference of the Society for Information Science organised by Malwad. By that time I had written a couple of papers and technical reports in this field, but I learnt a lot at the conference. I was also one of three people from Karnataka selected for a training programme at the Documentation Research and Training Centre (DRTC) of the Indian Statistical Institute. This Centre was highly reputed and had been established by Prof SR Ranganathan, a mathematician who came to be known as the father of library science in India. Prof Gadagkar, who was the Chair at that time, was very supportive, and paid my fee. There, I learnt programming languages for libraries, including C and FoxPro. Kumuda, who had a Bachelor’s degree in Computer Applications, had joined CES, and she was very good at programming. Dr TV Ramachandra, Kumuda, NN Janardhan Pillai and I wrote a program on FoxPro for the CES Library website. But the world of programming moves at a very fast pace, and languages become outdated. Document issue, renewal, recall, reservation – all of this had to be programmed, and I couldn’t find a software that covered the range of requirements of the library. The main library had purchased LibSys for around Rs 5 lakh, but we could not afford that.

The librarian at Aranya Bhavan, Usha Kumari, told me about a software called e-Granthalaya, and I wrote to Delhi to ask for it. They said they gave it only after the applicants had completed a training session. Reva Rani, a computer applications graduate who had joined the library, and I were selected for the training session. We dived deep into understanding how the software worked, installed e-Granthalaya version 3 and started an online system for issuing books. Until then people would issue books using their library cards and we would enter the details into a ledger. Word had gotten around that Yashwant Kanade from IISc knows how to use e-Granthalaya, and we were invited to train others. Reva and I went to the Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited library, the Tata Memorial Club library, Aerospace Engineering, and several other places to teach them how to install and customise the software.

Visit to the USA

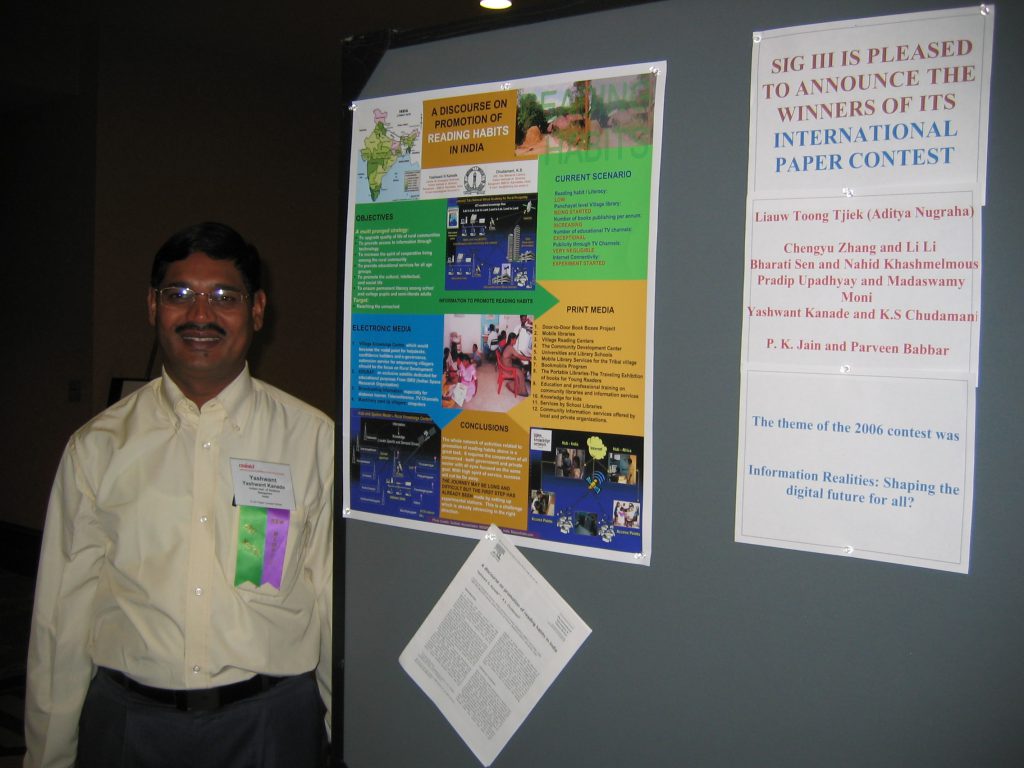

Chudamani and I had written a paper titled, ‘A discourse on the promotion of reading habits in India’ and submitted it to an international conference organised by the Association for Information Science & Technology (ASIS&T, formerly the American Society for Information Science and Technology) in the USA. Six months passed, and we didn’t hear back from them. One day when I went to the main library, she scolded me, “What is this, Kanade? You have become famous, won an international award and didn’t even tell us?” I got upset and said, “Ma’am, please don’t joke with me. How can someone like me get an international award?” and came back to CES. She was angry and called me on the phone, “Why did you get upset and leave in the middle of the conversation?” and asked me to come back to the main library. There she told me about an email informing us that our paper had been selected as one of the winners of the International Paper Contest for library and information science professionals in developing countries. I had also received it as the first author, but had (unintentionally) deleted it. I apologised to Chudamani.

Sharath Ahuja, technical officer at the Department of Organic Chemistry and a friend, told me, “Such opportunities are rare, don’t miss this chance. Let me know if you need any help.” I replied that I was not familiar with the procedure involved in going to America. He pointed me towards sources of funding that could sponsor my trip. Sir Ratan Tata Trust gave Rs 50,000 and the Dorabji Tata Trust helped with the airfare. I got a 12-year multi-entry visa to the USA, and went to Texas for the conference in 2006.

(Photo courtesy: Yashwant Kanade)

After that, I became recognised as a library scientist and was invited to give talks all over India. I am also a member of the Library and Information Science Forum of India.

Providing the best services

My job is service oriented. The right information to the right person in the right manner, that is the thumb rule of library sciences. And this service should be given with a smile. As part of the training, I would give an assignment: Say I receive a phone call at my desk. At the same time, a professor comes to ask for a book, another comes for a report, and a third person comes for an urgent xerox at the same time. How do I deal with this situation? The idea is to keep calm and talk to them one by one. And to prioritise.

The right information to the right person in the right manner, that is the thumb rule of library sciences

I teach the trainees about maintaining discipline and I have made a manual that includes a library workflow chart of basic and advanced information techniques.

Maintaining a physical library in this digital age is challenging. Even though we have a large and important collection that is not available online, we hardly have any visitors. Since the last 5 years, funds have been low and we haven’t purchased any new books. I have tried to create awareness, and made a big banner that says ‘Library and information services’ and put it up on the first floor. I also gave presentations about these services during student’s orientation programmes.

Almost four decades at IISc

In the 39 years since I have been here, the campus and the Institute have changed a lot. We had planted many saplings from the Western Ghats forests in IISc – that is now the mini forest. Dr TV Ramachandra created a channel to divert water from Sankey tank to this section of the campus. There are so many species of birds and trees here, you won’t find them outside. As you enter the main gate, you can feel the drop in temperature. I feel that it is really good for health, this environment.

However, what is missing nowadays is teamwork, or the feeling of community. Previously we would all meet and discuss our different projects in the seminar rooms. I feel that one can learn a lot through such sharing. Now people work individually and concentrate only on their own fields. Unless you read their papers, you won’t know what they are working on.

Take my own example – I had the opportunity to work on, and interact with people from many different projects. From electrical engineering to water and current flow, plant diversity, human ecology, economic use of plants, to library science. I learnt so many things along the way. To date, I have published several scientific papers and technical reports. I am very thankful to Prof Madhav Gadgil — he is the reason I am here and have reached this level. On every Teacher’s Day I wish him.

From the field to the farm

I really miss field work, that was a fantastic time. It was physically and mentally stimulating. I was born and brought up near a forest area and we were surrounded by singing birds, blooming flowers and flowing streams. We could jump into any pond, pluck any fruit. That was a different time altogether. But in the later years, I have been on some memorable treks with my close friends Ajith Kumar Maiya, a radiologist at the Health Centre and G Sudarshan, a Technical Officer from the Department of Electronic Systems Engineering.

I was a poor man when I came to IISc from my village. I never forgot that, and have helped many people from my village find their feet in this city. They were welcome to stay at my home, and I would help them with their education, and find a job. That has been my service to society. Maybe because of this, someone nominated me, and I was awarded the BDSA Dr Ambedkar National Fellowship Award for social work in 2012.

(Photo courtesy: Yashwant Kanade)

I have retired from IISc, but have started a new occupation – farming. I have bought 4.5 acres of land in Dongri village near Ankola. We have already planted coconut, arecanut and banana. After my son’s marriage in December, my wife and I will settle in Sirsi to look after our aged parents and to focus on the plantation.

As told to Samira Agnihotri