Tata medical philanthropy in colonial India was not confined to investing in bricks and mortar but also aimed at creating a culture of medical research

The emergence of modern philanthropy and the expansion of modern medicine in colonial India were closely intertwined, as medical historians have recorded. They note that medical philanthropy was simultaneously part of the colonial ‘civilising’ and nationalist modernising projects, and that Indian philanthropists, with encouragement from the colonial authorities, were engaged in a “joint enterprise” in founding permanent public utilities such as medical colleges, dispensaries, and large hospitals. Hospitals were in fact seen as the pre-eminent symbol of modern medicine. However, government officials gradually became suspicious of Indian charity, less amenable to cooperation, and even reneged on their commitments, revealing the fault lines in the “joint enterprise.”

From 1890 to 1932, the Government of India was engaged in organising medical research and founding of bacteriological laboratories and medical research institutes. The focus of these was primarily the manufacture of vaccines and sera for protecting army personnel. As Indians began to demand the Indianisation of the Indian Medical Service (IMS), medical research became a site of contestation and anti-colonial struggle. The IMS, already experiencing a decline in European recruits, attempted to retain its European character by emphasising prospects and opportunities for medical research.

Medical research was a state responsibility and imperial preserve with the Medical Research Department dominated by European doctors from the IMS and the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). Indians were employed in subordinate positions, and the Indian National Congress, Indian nationalists, and medical professionals such as Jivraj Mehta decried inadequate or lack of Indian representation in senior scientific positions and in the Governing Bodies of medical institutes.

Nevertheless, medical research institutions established to protect and promote IMS interests – the Indian Research Fund Association, the Pasteur Institutes and the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine (CSTM) – all received generous donations from Indian philanthropists. Despite this, the perception prevalent among British officials and even educated Indians was that Indian philanthropy neglected medical research. For instance, IMS officers WB Bannerman and Leonard Rogers, who proposed CSTM, bemoaned the absence of interest amongst educated well-off Indians, with Rogers suggesting that an ‘Indian Rockefeller’ come forward to advance genuine medical research throughout the country. Editorials in Current Science, Calcutta Medical Journal and Science and Culture lamented the lack of awareness among affluent Indians of the benefits of promoting medical and scientific research and underscored their responsibility to support and inculcate in Indians an interest in medical research. Meanwhile, the AV Hill Report (1945) pointed out that some wealthy Indians had indeed made considerable benefactions to science, medicine and technology, and mentioned in particular the Bombay-based Tata family.

The Tata Research University and medical research

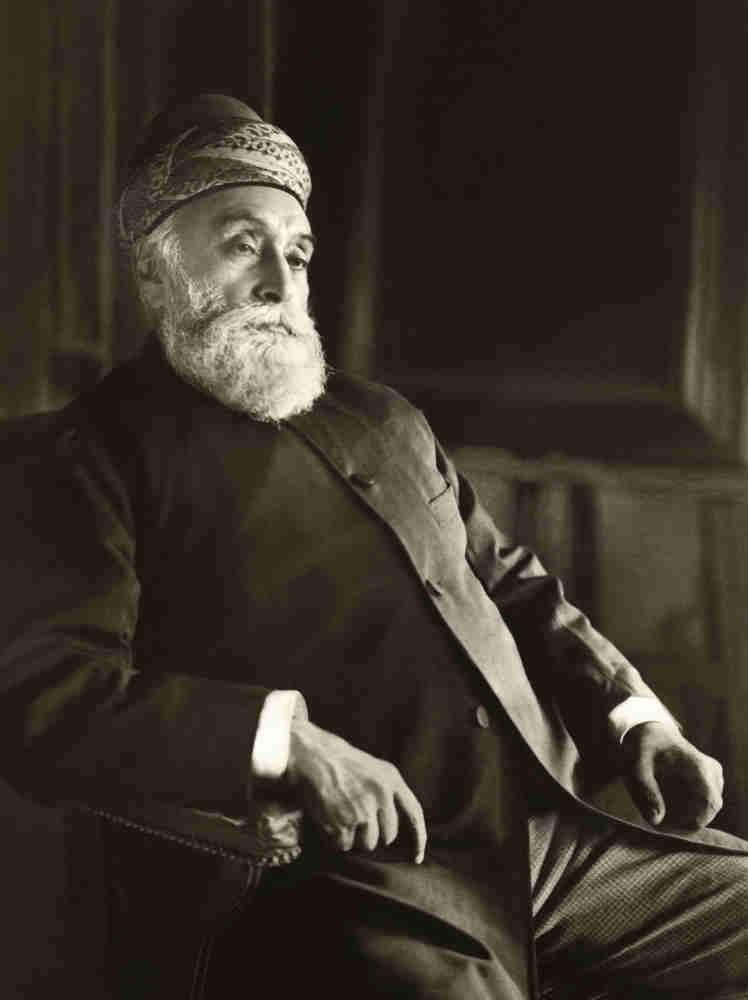

Jamsetji, the founder of the Tata business and industrial house, was also a well-known philanthropist who believed in constructive and purposeful gifting. “What advances a nation or a community is not so much to prop up its weakest and most helpless members,” he wrote, “as to lift up the best and most gifted so as to make them of the greatest service to the country. I prefer this constructive philanthropy which seeks to educate and develop the faculties of the best of our young men.” He aspired to create a culture of research that would benefit the country and, during his life, he set up technical training and science research institutions. Jamsetji’s sons Dorabji and Ratan would also go on to will their property for the advancement of education, science and medicine.

The Tatas were particularly keen on medical philanthropy; to institutionalise and professionalise medical research, Jamsetji Tata and his son Dorabji proposed various schemes. The first of these was the Research University proposed as a “joint enterprise” with the colonial government in Bombay (1896) incorporating scientific, technical and medical research. This marked the beginning of Tata’s various endeavours to endow medical research in India. The principal ideas underlying the Tata schemes, drawn from an exceptional world-view discussed above, challenged the narrow colonial conception of bacteriological research restricted to the production of sera and vaccines, and contested imperial control over medical research. This caused much consternation among colonial authorities and the schemes were met with a mixed response.

The Tatas were particularly keen on medical philanthropy

Rev Machichan, a member of the University Committee, observed that the University was not meant to be a “mere handmaid to industrial progress” but a “seat of intellectual and scientific culture” dedicated “to the cultivation in India of the spirit of research.” The objectives of the University were “to provide for advance [sic] instruction and to conduct original investigations into all branches of knowledge… likely to promote the material and industrial welfare of India” that included: scientific and technological education; medical and sanitary education, including research in bacteriology; and studies in what are currently termed humanities and social sciences.

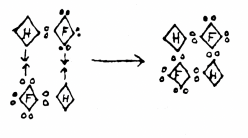

Jamsetji’s scheme coincided with a proposal by some Indian princes to commemorate the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria’s coronation in 1897 by setting up a “medical research institute which would investigate the unsolved problems of health and disease in India.” The Government agreed that there were benefits. The princes recommended Waldemar Haffkine, the Russian bacteriologist then employed with the Bombay Bacteriological Laboratory (BBL), as Director. Jamsetji invited Haffkine to negotiate an amalgamation of the proposed medical research institute with the Research University and to expand its scope beyond bacteriology to include hygiene, and pathological and physiological chemistry. Jamsetji, inspired by German research universities, wrote to Haffkine, “Our whole Bill has been drafted on the assumption that it is best for the interests of Higher Education to leave the Professors unfettered in teaching and research. Lehrfreiheit [academic freedom] is the most important lesson that we have learnt from Germany.” The model was, however, the Johns Hopkins University, the first university in the US to introduce postgraduate teaching and which enshrined a great deal of autonomy and academic freedom.

Haffkine sought government sanction for medical postgraduates of the Research University to be chosen to study and work in the BBL. This move, he pointed out, would provide them with opportunities to develop their scientific skills and conduct pure research in India – instead of sending them abroad – that would be “used for the study and combating of Indian diseases” and through them spread the interest in medical research among the wider Indian community. The aim “was to give Indian students the opportunity of achieving fame in the world of science, and also to assist the people and the country in various departments of life.” Among the students, “those who displayed more than ordinary gifts might look forward to being placed on the staff of the Bacteriological Institute of the Research University when such an independent branch came to be established. On the other hand, a class of men would be created from amongst whom the Government and the country could recruit officers for special problems and appointments…such as the plague.”

Both Tata and Haffkine envisioned a role for medical research beyond the laboratory, aiming at creating a culture of scientific research in India

Haffkine pointed out that in France the Ecole des Hautes Etudes alumni were the foci for the radiation of scientific culture in the country and Indians needed to bear this in mind. Both Tata and Haffkine envisioned a role for medical research beyond the laboratory, aiming at creating a culture of scientific research in India.

There were differences of opinion within the Government, with some officials arguing that bacteriological and medical research should remain in the government domain. On the other hand, AHL Fraser, the Home Secretary, noted that the part that most appealed to him about the University concerned “training doctors and facilitating research in respect to problems connected with health and disease.” Jamsetji’s scheme was viewed by the Indian elite and middle class as a patriotic act and one that would confer lasting benefit on the people of India. William Ramsay, the British advisor to Tata’s University scheme, wanted it to concentrate on scientific research alone. Around the same time, the Viceroy Lord Curzon unfavourably viewed the Princes’ Health Institute and turned it down. He also considered Ramsay’s proposals for the Tata University as too ambitious and narrowed down its scope to basic sciences and technical research. It was, however, eventually established as the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bangalore. The vesting order for IISc was passed in 1909 and the foundation stone of its Main Building laid in 1911.

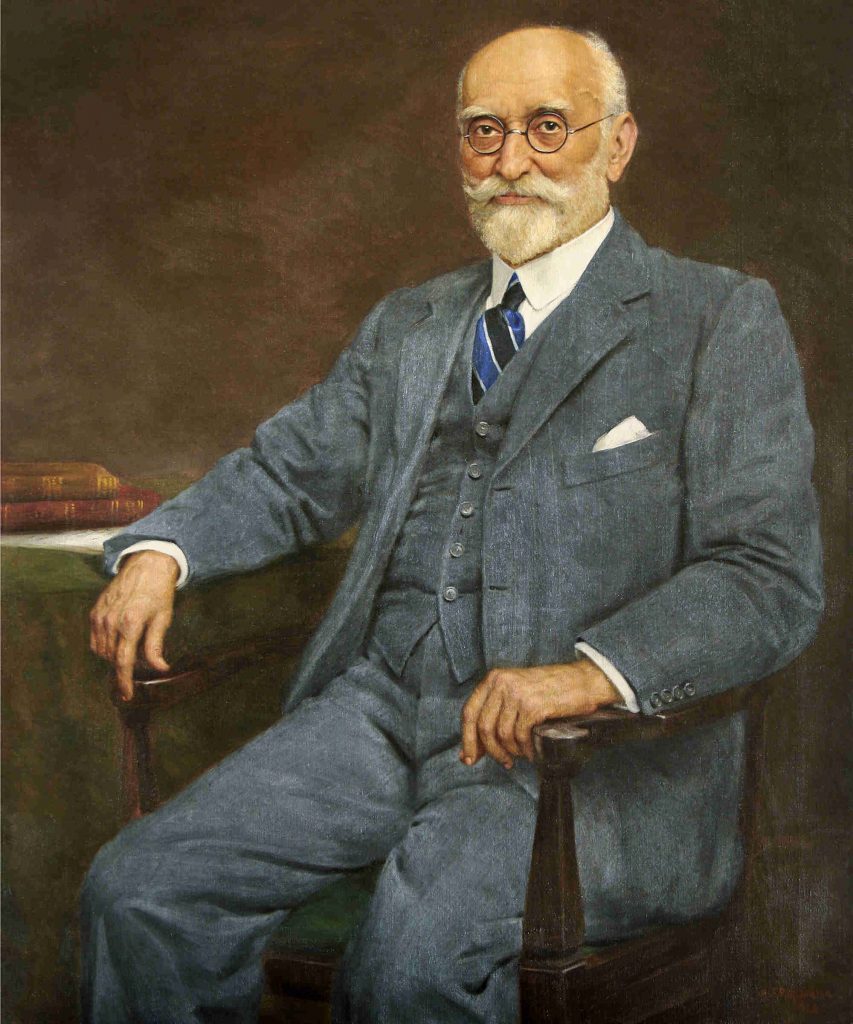

Dorabji’s persistence

Jamsetji passed away in 1904, but his sons Dorabji and Ratan continued pursuing plans for a medical faculty at IISc. They unsuccessfully attempted to persuade Charles Martin, Director of the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine, to take over as the Director of IISc to ensure that medical research would acquire prominence in the Institute. Ramsay, fearing a medical bias and a shift from the technical focus that he had been consistently espousing, argued that enough medical research was being done in India. Martin himself declined the offer, observing that the scope of the Institute was too narrow and it appeared unlikely that medical work would ever become part of the Institute.

Jamsetji passed away in 1904, but his sons Dorabji and Ratan continued pursuing plans for a medical faculty at IISc

Dorabji also sought opinion from Rogers of CSTM and Glen Liston of the BBL (who had proposed a School of Tropical Medicine in Bombay for Indians), and from other experts in Britain on how he could best endow medical research in India. In September 1912, he wrote to Morris Travers, the first Director of IISc, seeking to ascertain how his bequest for two medical chairs in IISc could be utilised for research in tropical medicine and in a manner that would be “valuable alike to the cause of science and the progress of India.” Dorabji did not want to invest in ‘brick and mortar,’ but believed that the money would be best utilised to pay the professorial staff recruited for their ability, temperament, knowledge and skills for research to engage unfettered in the production of knowledge. But Travers put up stiff resistance.

Dorabji persisted, and in 1917 invited R McCarrison (IMS) to prepare a scheme for medical research. McCarrison recommended that Indians themselves establish an “Indian Institute for Medical Research” on the lines of the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research (established in 1901). India, he noted, had her Rockefellers and millionaires who he felt confident would respond generously to achieve in medical research what other countries had. He also argued that the future of western medical science in India lay with Indians.

Dorabji offered endowments to both the Bombay School of Tropical Medicine and the Central Medical Research Institute in Delhi, medical institutes which the Starling Report (1920) had recommended establishing. The schemes ostensibly had to be abandoned due to the recommendations of the Retrenchment Committee (1922) on government expenditure. However, as Dorabji explained to WS Carter of the Rockefeller Foundation, who was conducting a survey of medical education and research in India, the real reason in both cases was government unwillingness to accept his conditions: that the government match his endowment with a contribution of its own; that these should be postgraduate institutes; faculty recruitment not be restricted to the IMS; appointments be made by a Committee of the Royal Society; faculty salaries be higher than those prevalent in government institutions; and, a ban on private practice, which caused much disquiet among European IMS officials.

In 1941, the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust inaugurated the Tata Memorial Hospital, incorporating a cancer research centre

Dorabji sought Carter’s opinion on “the possibility of doing something to develop medical research in Bombay for the good of all of India and independent of Government” and the best means of promoting research. Carter suggested the establishment of fellowships to train Indians as research workers. In 1928, Dorabji donated a grant for a Pathology Laboratory at Bombay’s Grant Medical College. When his wife passed away due to leukaemia, he set up the Lady Tata Memorial Trust in 1932, the first Indian Trust to offer private funding to individual medical researchers in India. Its London-based Scientific Advisory Committee offered research grants and scholarships to leukaemia and cancer researchers globally. Some of Europe’s leading researchers were recipients of this benevolence. In 1941, the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust inaugurated the Tata Memorial Hospital, incorporating a cancer research centre. Today, this hospital continues to remain a symbol of the Tatas’ enduring commitment to endow medical research in India.

Shirish N Kavadi is a researcher with interests in the history and politics of health and medicine, and a Visiting Professor at the Symbiosis School for Liberal Arts, Pune. He is presently working on a book manuscript on Tata philanthropy and medical research in colonial India.