Hunting strategies of predatory bacteria

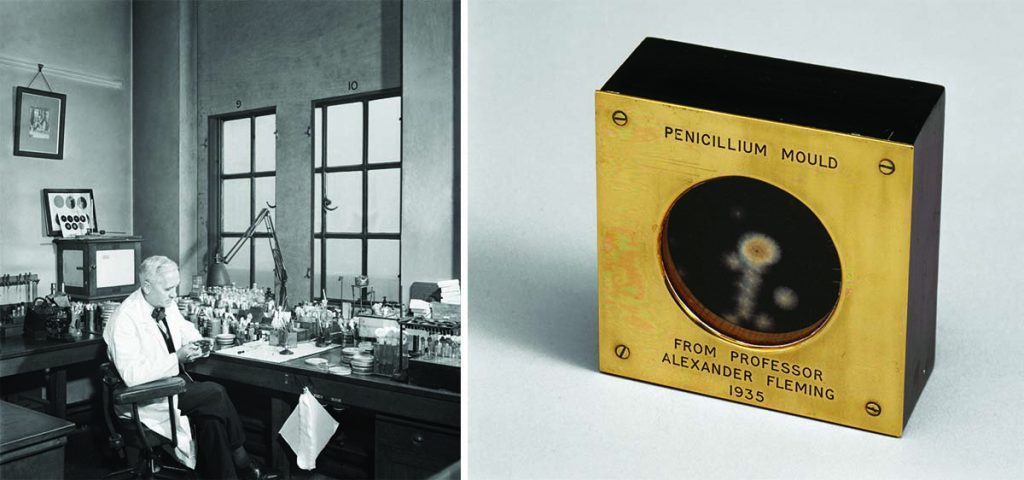

In 1900, a young medical student named Alexander Fleming was studying at St Mary’s Hospital Medical School in London. Fleming also served in the London Scottish Regiment of the Territorial Army, where he became an expert marksman. His talent for shooting caught the eye of the captain of St Mary’s rifle club, who hatched a clever strategy – if Fleming chose a research career over surgery, he would stay at St Mary’s and in the rifle club.

The captain succeeded in his plan and persuaded Fleming to pursue research under Almroth Wright, a pioneer in vaccine therapy and another member of the rifle club. It was a decision that changed the course of clinical medicine. While serving in the Army medical corps during World War I, Fleming witnessed the death of fellow soldiers due to infections from field wounds. Antiseptics failed to kill certain bacteria that thrived deep in these wounds. Returning from the war to his lab at St Mary’s in 1922, Fleming discovered lysozyme, an enzyme found in tears, saliva, skin, hair, and fingernails that inhibits bacterial growth. At that time, very few people realised that this discovery was just the beginning of a new age of antimicrobials.

A few years later, Fleming was studying Staphylococcus bacteria at St Mary’s Hospital. One day in September 1928, after returning from a long vacation, Fleming was surprised to see that the Petri plate he had forgotten to discard had a mould growth and a zone of clearance – a bacteria-free circle around the mould – indicating that the Staphylococcus bacteria in that zone had died. Piqued by this observation, Fleming investigated further and identified a compound secreted by the mould that effectively killed the bacteria, which he initially referred to as ‘mould juice’. This compound was later named penicillin.

Fleming faced challenges in purifying penicillin from his mould juice, and it was not until 1940 that scientists Howard Florey and Ernest Chain were able to purify and demonstrate penicillin’s therapeutic effect against various infectious diseases, saving millions of lives in World War II. The trio was subsequently awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1945, marking the rise of the antibiotic era.

Antibiotics are the byproducts of a millennia-old evolutionary arms race

Fast forward 97 years, and this golden era has become overshadowed by the rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), fueled largely by the overuse of antibiotics. While much is known about how antibiotics like penicillin have saved lives, a lesser-known fact is that they are largely defensive chemicals produced by bacteria to attack other bacteria or organisms like yeast when they compete for food, resources, and space. They are the byproducts of a millennia-old evolutionary arms race.

“We must remember that neither antibiotics nor antibiotic resistance is new. Antibiotics have always been used by microbes to compete with one another,” says Saheli Saha, former PhD student in the Department of Microbiology and Cell Biology (MCB), IISc.

Scientists like Saheli are increasingly realising that bacterial predation is more than just a story of war and death. These interactions are not limited to microbes in the wild – our body too houses trillions of bacteria engaged in complex combative and cooperative interactions. Some probiotic bacteria help to maintain harmony in our gut, while others may fight with them, disrupting this balance. This imbalance can lead to dysbiosis – a condition in which harmful bacteria outnumber beneficial ones, which is often worsened by the overuse of antibiotics. “One of the leading theories is that this dysbiosis is a result of competition for nutrients or space,” explains Akshit Goyal, faculty member at ICTS-TIFR, Bengaluru.

Understanding the delicate balance of bacterial harmony is critical, given that the number of bacteria in the human body is approximately equal to the number of human cells. More broadly, exploring competitive bacterial interactions can potentially lead to new antimicrobial therapies. In the quest to combat AMR, scientists are turning to nature’s fiercest fighters.

Hunting in packs

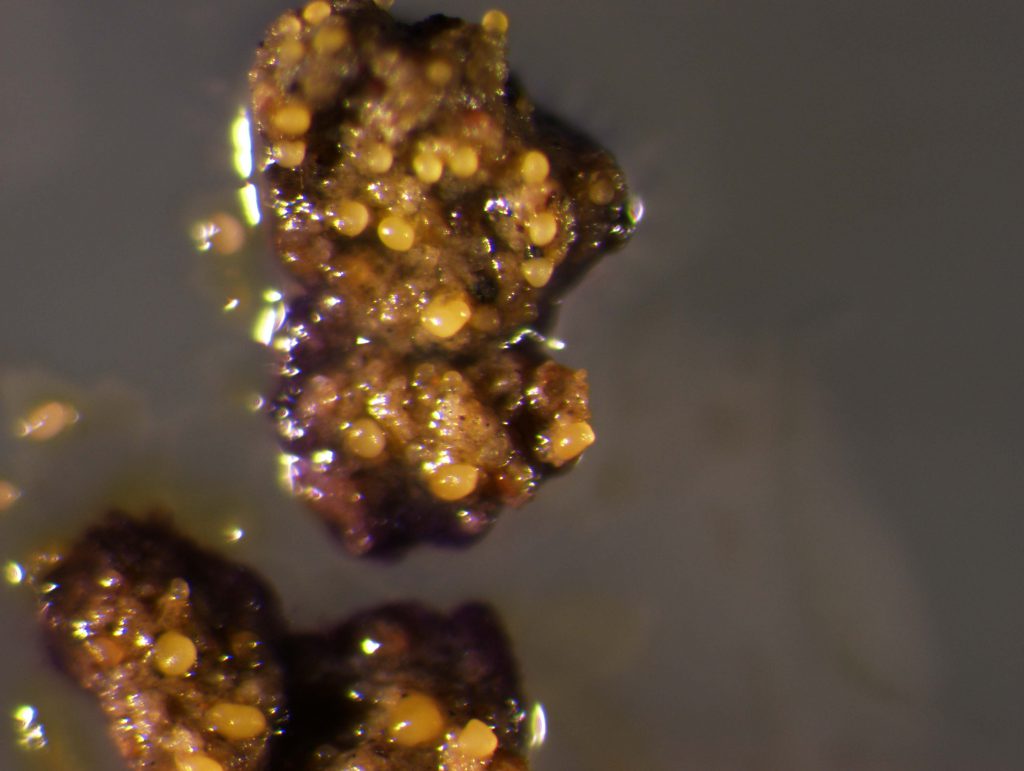

Living in the soil beneath our feet, Myxococcus sp. is a fascinating bacterium known for its fearsome predatory skills. It attacks its prey – usually other bacteria, fungi or amoeba – by lysing it (breaking down its cell membrane) from the outside. It releases a cocktail of different chemicals like toxins, antibiotics, and enzymes that digest its prey. “Myxococcus can make a soup of its prey and just drink it up,” says Samay Pande, Assistant Professor in MCB.

Myxococcus also hunts through contact; it releases lytic enzymes when it touches its prey, basically stabbing and killing it.

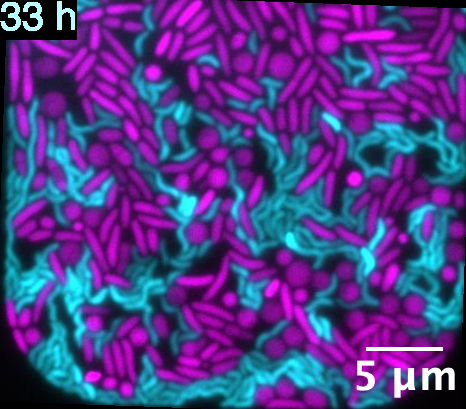

What makes Myxococcus’ attack style truly remarkable is that it does not hunt alone, but as a coordinated pack, like wolves

But what makes its attack style truly remarkable is that it does not hunt alone, but as a coordinated pack, like wolves. “It is not just one cell that does it. Every [Myxococcus] cell releases these enzymes, and they hunt and eat together,” Saheli adds.

To hunt in packs, Myxococcus employs several tricks, such as coordinated swarming and cell-to-cell signalling, which can fool and lure prey.

“There is an old study published in Nature in 1993 titled ‘Fatal Attraction,’ which demonstrated that the prey, E.coli, shows chemotaxis – it moves towards the predator Myxococcus xanthus colony. This happens because M. xanthus secretes an attractant compound that lures E.coli towards it,” Samay explains.

Strangely, Myxococcus does not always die, even when starved. Sometimes, they can also enter a dormant state in which a few cells can come together and form a hibernation structure called a fruiting body. When conditions become favourable again, they re-germinate, start hunting and eating their prey, releasing, among other chemicals, antibiotics.

Samay notes that the ability of Myxococcus to produce varied chemicals and attack a wide range of bacteria, fungi, and amoeba makes it a vital source for new antibiotics. “Resistant bacteria are no longer killed by antibiotics, but they still haven’t developed resistance to predation [by other bacteria],” he says. “Microbial predators have ways to kill antibiotic-resistant bacteria, so a solution already exists.”

Poisoned darts

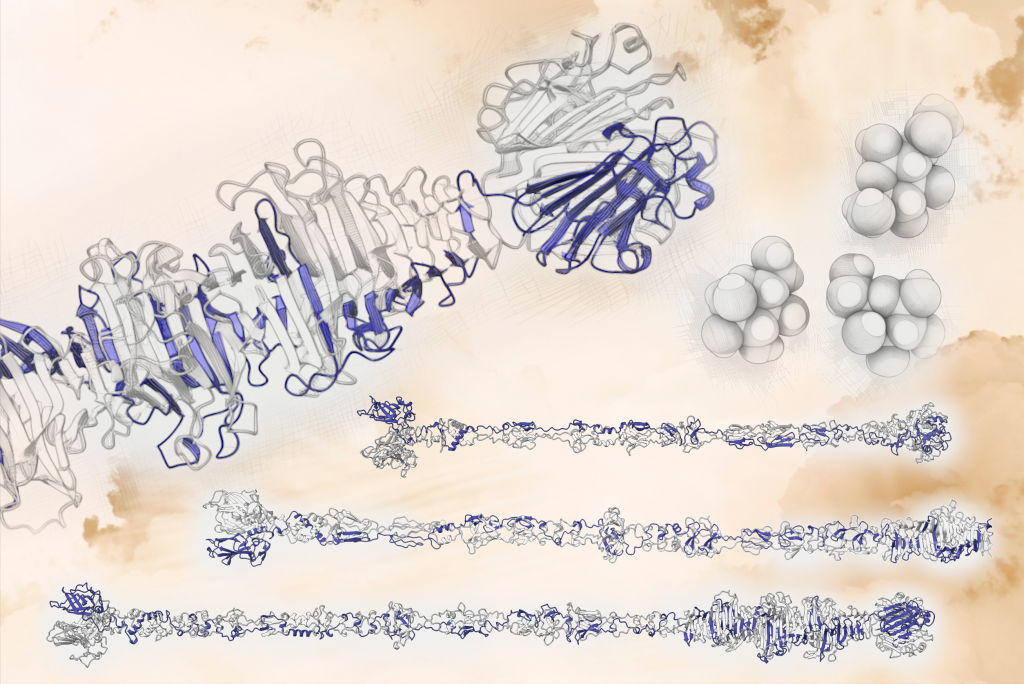

Unlike Myxococcus, which attacks in groups, some bacteria are solitary hunters, such as Vibrio anguillarum, a coastal ocean dweller. It can lyse and consume the cellular contents of its prey by using a nanoscale speargun-like weapon called the type VI secretion system (T6SS). This weapon has a contractile part that looks like an injection needle with a tip bearing toxins. The bacterium injects this contractile part into neighbouring cells to deposit the toxins. To avoid accidental death from being stabbed, its relatives carry antidotes to the toxin, whereas non-relatives, lacking such protection, often meet a grim fate.

Having the T6SS provides a competitive advantage by removing rival bacteria like Vibrio cyclitrophicus that compete for the same resources. With a broad host range, T6SS-equipped bacteria employ a variety of killing mechanisms. Some methods involve chopping DNA fragments inside prey cells, while others target their cell wall, the outer layer. These aggressive predators also, at times, kill prey not just for food but also for movement – they use a fast-acting toxin that essentially clears any cells and cell debris in their way.

Some Vibrio species with T6SS also drill holes into the prey’s cell membrane and inject toxins into cells, making them leaky. This leakage results in the loss of nutrients, which the killer can utilise for their own growth. When V. anguillarum is unable to grow normally, it can damage neighbouring cells and thrive on the released contents. “It is like you are stabbing someone and just letting the blood slowly come out,” explains Glen D’Souza, Assistant Professor at Arizona State University (ASU).

Harnessing Vibrio anguillarum’s steerable nanoscale needles could help develop more targeted drug delivery systems

The ability of such bacteria to inject toxins with high precision could come in handy in developing new drug delivery systems for humans as well. Existing treatment regimens involve antibiotic pills – when taken orally, they are absorbed into the blood and carried across the body by the circulatory system. But harnessing V. anguillarum’s steerable nanoscale needles could help scientists develop more targeted delivery systems.

Eating from within

Unlike other bacterial predators, Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus – found both on land and in water – kills its prey from the inside. Its name comes from the Greek word for leech (bdella), both for its shape and way of life. Its curved body allows it to physically enter the prey’s periplasm – a gel-like space sandwiched between the latter’s membrane layers. Inside, it builds itself a cosy niche and starts consuming the cell from the inside.

“These extraordinary physiological adaptations are still not understood fully – how they manage to cut a hole in the membrane, come through it, and then seal the hole behind them. It’s just amazing when you watch it happen; you almost can’t believe it,” explains Andrew Lovering, Professor at the University of Birmingham.

When Bdellovibrio invades a prey cell, the latter takes on a circular shape – a process known as the rounding effect. Scientists initially thought that this change was to provide the predator ample room to reproduce, but soon they realised that there was more – the effect also stopped other predators from coming in. “The rounded cell sends a signal to other predators that the prey cell has already been invaded, and they have to go find another one,” adds Andrew. Bdellovibrio genomes encode receptors that allow them to sense chemicals that pinpoint the prey’s whereabouts.

In addition, the prey population does not gain resistance to Bdellovibrio because of its unique attacking strategy, which involves a mix of physical and chemical combat. Andrew says, “The prey cannot easily escape predation by picking up a mutation or extra genes that provide resistance. Therefore, investigating natural predators of bacteria reveals effective targets for antimicrobial intervention and could open up new possibilities for developing antibiotics.”

‘If we try to understand these bacterial interactions, we can use them like contract killers – find targets and deliver toxins’

However, to exploit such predation strategies, scientists will still have to decode their complex interactions fully. In Vibrio, for instance, we do not fully know how they locate the prey. “Their foraging cues are not known,” Glen says. “If we try to understand this, we can essentially use them like ‘contract killers’ – we can train the [predatory] bacteria to go and find specific targets and deliver toxins. This could be a potential [solution] … to tackle antibiotic resistance.”

Andrew also points out that such strategies could be used in combination with existing antimicrobial strategies. “Using combination therapy generates much fewer issues of resistance; you could even use two different predators as long as they didn’t attack one another.”

Samay, however, cautions that any new therapeutic solutions will need to be made “future-proof” to avoid the obsolescence that antibiotics fell prey to. “All infectious agents can evolve rapidly. Even in the case of antibiotics, the mistake was that we did not ignore [the possibility of resistance], but we sort of pushed taking care of it to a later time,” he explains. “Now, all of us are aware and cautious. We must not repeat the same mistake.”

(Edited by Ranjini Raghunath, Abinaya Kalyanasundaram)