How citizens are helping collect research data

On the rare occasion that you break away from the tedium of overflowing inboxes to listlessly stare into space, something extraordinarily fascinating could catch your attention. It could be a stray dragonfly perched on the window ledge, or perhaps a tree with a huge canopy farther away. It could be said tree’s oddly bending trunk that holds your interest, or the beautiful blooms decorating its branches. Either way, that tree now occupies a tiny corner of your mind and likely your camera roll.

This simple act of observing and documenting is what brought pini-beraliya (Doona ovalifolia) – once declared extinct in the wild – back to life and into the scientific spotlight. For decades, a single cultivated specimen of this tree existed at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Sri Lanka’s Peradeniya like a living relic. In 2018, however, gem miner and plant enthusiast Lasith Prageeth, in response to a Facebook post that requested sightings of the species, shared photos of a towering tree from his village, Ayagama. Flower specimens that Lasith collected a year later led botanists to confirm that the forest giant was alive after all!

The discovery set off a wave, with conservationists tracing a few more surviving trees along riverbanks in Sri Lanka’s western provinces. Today, Lasith and local school children have become the unlikely stewards of the species. Every few days, they water and nurture hundreds of its saplings in community-run nurseries. What started as a chance click shared online has since mushroomed into a national effort to restore one of Sri Lanka’s critically endangered trees.

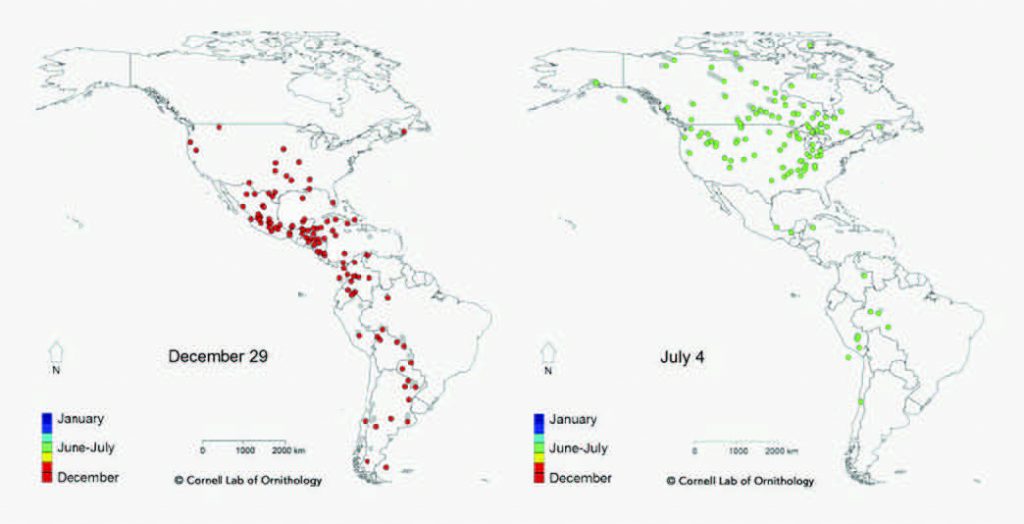

Thousands of kilometres away, a similar spirit of collective curiosity has transformed birdwatching into a powerful tool for ecological research. Loyal birders recorded and uploaded more than a million observations of about 118 bird species across the Western Hemisphere on eBird, a citizen science platform launched by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in 2002. Using the data from 2002 to 2014, the lab created a vivid, continent-spanning animated map of the species’ annual migration between their breeding and wintering grounds in North, Central, and South America – something no single researcher could have tracked alone. This also revealed some fascinating insights into the birds’ preferred routes, movements and behaviour.

Around the world, such collaborations between everyday nature enthusiasts and scientists are blurring the lines of how ecological research takes place. Armed with smartphones, internet access, and curiosity, citizens – from students and birders to farmers and divers – are now helping collect real scientific data. This participatory movement, known as citizen science, is transforming how biodiversity is documented, monitored, and protected.

“Citizen science produces data at larger spatial and temporal scales and resolutions than individual projects can,” says Kartik Shanker, Professor and Chair of the Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES), IISc. “But it may be even more important as a tool for citizen engagement.”

Climate clues

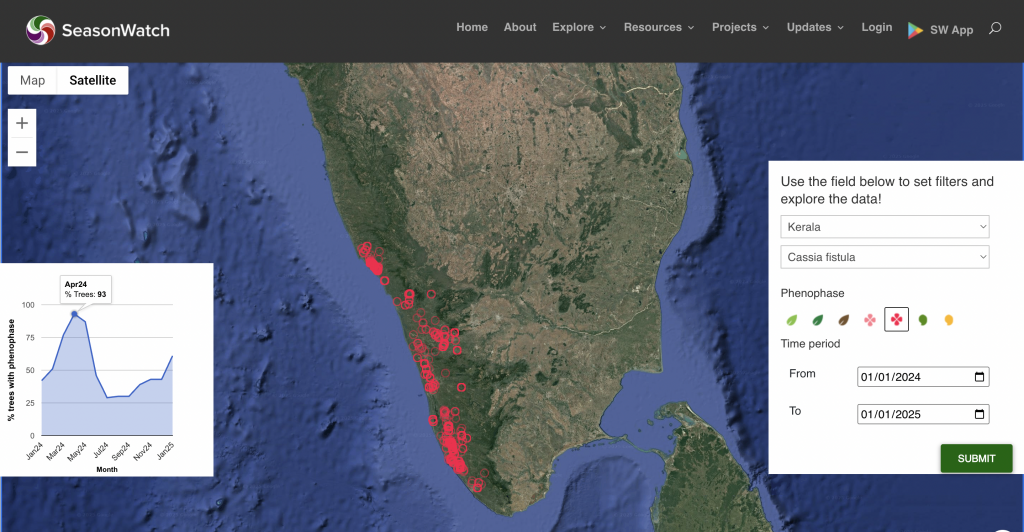

In India, citizen science in ecology became more widespread in the early 2000s, when naturalists and scientists recognised the power of collective observation in a biodiversity-rich but data-poor country. The India Biodiversity Portal (IBP), launched in 2008, was one of the first attempts to build an open-access database where anyone could upload and validate species sightings. It was followed a few years later by a Nature Conservation Foundation initiative called SeasonWatch. Launched in Kerala in 2014, it enlists interested individuals, even schoolchildren, to record when trees flower or fruit – revealing how climate change may be altering the rhythm of India’s seasons.

For instance, the flowering of the golden cascade or Kannikona (Cassia fistula) would historically peak during the festival of Vishu, when it would be a part of the festivities. However, locals reported on SeasonWatch that the flowering now peaked earlier than Vishu, and seemed to recede during the festival. They also found fewer flowers throughout the year.

“We asked locals to record these observations and upload this data on our portal to confirm that there were notable changes in flowering patterns. Although this data isn’t yet enough to prove that climate change is altering flowering patterns, it lays the groundwork for much-needed baselines of fruiting and flowering periods – data that is scarce in India. Tracking deviations from these baselines could reveal the impact of climate change on trees,” says Sayee Girdhari, Project Coordinator for SeasonWatch.

Another interesting pattern that came to light through citizen contributions was that the timing of flowering and fruiting shifts significantly based on latitude. Flowering begins sooner in the south (like Kerala or Tamil Nadu) and then progresses north, forming a wave pattern through Maharashtra and finally reaching Delhi.

Since its inception, SeasonWatch has accumulated over nine lakh observations

The other perk of this project is public engagement. Since its inception, SeasonWatch has accumulated over nine lakh observations. Active participants (those who have added at least one observation) include 2,890 individuals and 3,476 schools, including schools participating through the Malayali newspaper Mathrubhumi’s SEED (Student Empowerment for Environmental Development) programme. Some committed participants, like teachers and students in Kerala, have been making observations for over 10 years since the project began.

“We work with trees, which is not a very charismatic group,” says Sayee, with a laugh. “By involving people in such a project, they begin to view trees as friends and develop an emotional connection with them. Trees attract so much biodiversity and form beautiful, interesting relationships with other fauna. Our citizen scientists get to observe other organisms’ life cycles as well. So, trees become sort of a segue into learning more about nature and connecting with ecosystems around them.”

Diving deep

While projects like SeasonWatch reveal changes unfolding on land, other citizen scientists have been documenting equally profound shifts below the sea’s surface.

In the Andamans, islanders had long noticed dramatic changes in coral and fish populations since the 2004 tsunami. These changes started getting recorded more systematically through ReefLog, a citizen science initiative launched in 2015 by the Dakshin Foundation, a non-profit led by Kartik Shanker.

ReefLog is driven by the desire to get locals to participate in the conservation of the ecosystems that they are a part of. Citizen divers are trained by diving professionals to conduct surveys and collect data on coral and fish populations.

“During one of my interactions with a veteran dive professional from Havelock, I learnt that there was this particular reefscape close to Long Island that was full of vibrant stag horn corals. It was completely wiped out after the tsunami, and now, barrel sponges are taking over that same area,” says Samar Ahmad, Programme Associate at ReefLog.

“Another recent observation by the dive professionals in Havelock Island is a sudden population increase of a fish called the common bluestripe snapper (Lutjanus kasmira). A few years ago, the species was present in individual groups of maybe 10-20. Now, at the very same dive site, there are some 80-100 individuals together at any given time,” she adds.

On the other side of the Indian Peninsula, a Dakshin Foundation researcher, Mohammed Serfas Khan, is actively tracking the movement of green sea turtles in the Lakshadweep Islands. One of the chapters in his research involves identifying individual turtles using high-resolution photographs of their unique facial patterns (a method known as photo identification), which are similar to human fingerprints. These photographs of turtles were captured by local scuba divers from the various islands of Lakshadweep.

“These local divers don’t require any GPS. They know exactly where to find the turtles,” says Serfas, with a grin.

The project began in 2016 and aims to map green turtle movements and seagrass habitats for their conservation and management. When the project started, a key driver for the research was addressing the human-turtle conflict prevalent at that time – turtles were altering fish nurseries due to overgrazing in seagrass meadows, inadvertently impacting local fishermen. But now, things have improved.

“The project has helped change the local perception of turtles from pests to valuable organisms. Scuba divers and locals have learned more about turtles, leading to increased respect for the green turtles,” says Serfas.

Citizen-collected visual data can sometimes reveal fascinating adaptations in animals. For instance, in one of the videos recorded by the divers, a green turtle was seen navigating a plant defence strategy rather cleverly.

Citizen-collected visual data can sometimes reveal fascinating adaptations in animals

The tall and long-lived seagrass species in Lakshadweep have naturally been replaced by shorter, fast-growing species to combat overgrazing by sea turtles. Their shorter length makes it harder for the turtles to graze effectively as the blades are closer to the sand. The video captured by the citizen scientist diver showed the green turtle adapting to this challenge by pushing the sand aside with an indelicate swish of its front flippers before diving in to chomp on the seagrass.

Another example of video evidence bringing new animal behaviour to light lies in ecologists Sangeeta Sharma Pokharel and Nachiketha Sharma’s 2022 study on elephants’ response to death. Witnessing instances of an elephant’s death is rare in the wild, and Sangeeta had only ever observed one case in three years of intensive field work. So, she and her colleague turned to online videos for data.

By mining publicly available footage on YouTube, using search terms such as “death of elephants” and “elephant reactions to death,” the study identified 24 cases revealing how elephants interacted with deceased family members, such as patting them with their trunks. In a BBC article, Nachiketha called “calf carrying” – where elephants picked up a dead calf with their trunk or tusks and dragged it – the “most striking thing” observed.

A double-edged sword

While these videos offered insights into how elephants behave, they also raised the possibility of bias. For instance, the researchers had no way of confirming if the animals’ behaviour was organic or influenced by human presence. Citizen science, which relies heavily on voluntary contributions, has inherent risks of such bias.

In the ReefLog initiative, where participants collect data on multiple species, observers are likely to over-report conspicuous or charismatic species. Conversely, cryptic or unremarkable species are often under-reported due to their reduced detectability during surveys. “It’s like how, in birdwatching, nobody reports the crows and the doves, but everybody is reporting the raptors,” Samar says.

Moreover, data collection is geographically and seasonally skewed because most dives happen at popular tourist areas and during the peak diving season (November to March/April), leaving less-visited reefs and other months underrepresented.

To manage these biases, ReefLog filters the observations and seeks out confirmation from professionals at dive centres and other fish and coral taxonomy experts.

Platforms like iNaturalist employ similar methods, preventing any AI-generated content from misleading data entries. Samar notes that she often encounters videos on social media that are so difficult to discern as real or AI-generated. “Fortunately, some people who use AI to generate content are using tags like ‘AI-generated’ in the captions,” she says.

Another flipside to this wave of digital documentation is that not all recordings are driven by curiosity – some are fuelled by the irresistible lure of a selfie. In a viral clip from August 2025, a tourist in Karnataka was seen trying to snap a selfie with an elephant. The wild animal, however, was not impressed and began to chase the man, reportedly pantsing him. According to a bystander, the sudden camera flash provoked the elephant.

Samar acknowledges that citizen science may contribute to the burden of unregulated tourism. “If the government and the local authorities can bring in responsible tourism, then the benefits of citizen science would definitely outweigh the risks,” she says.

Citizen science may not solve the biodiversity crisis overnight. But it might be changing something more fundamental: our relationship with the living world. In a time of algorithmic feeds and synthetic media, it’s certainly teaching people to pause and really look again – to pay attention, to record, to care. Serfas notes, “Citizen science projects have the power to change local perceptions around species. For the contributors, it can create a sense of pride, curiosity, and appreciation.”

(Edited by Abinaya Kalyanasundaram)