The alluring mystery of an amorphous solid

Glass is everywhere. You scroll over it on your phone, you drink from it, it’s in the spectacles perched on your nose and in the windows of your house. But how does it form?

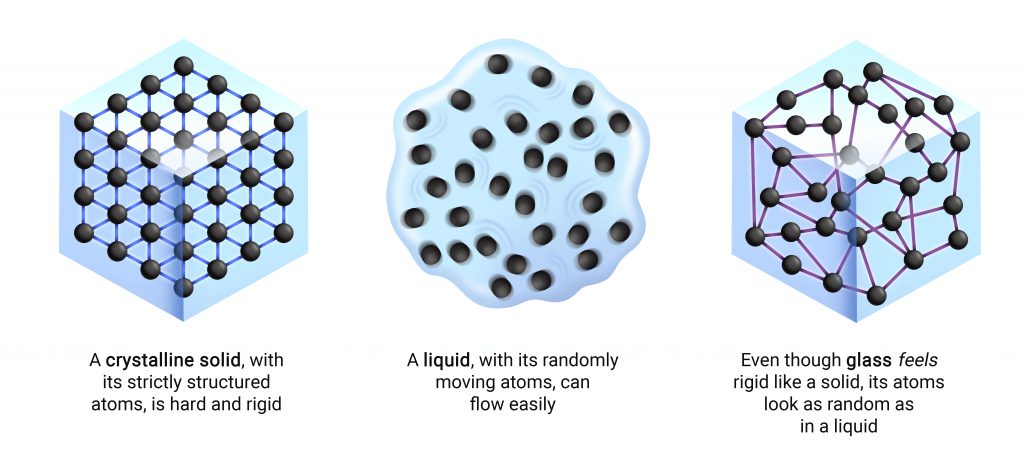

To picture that, imagine molten glass. As a liquid, it can flow; its atoms are free to move however they please. Then, imagine cooling it down. As it gets colder, the once unrestricted atoms are forced towards stillness; the speed with which they jiggle about starts to decrease. But as they slow down, they do not line up into neat, ordered rows, like in an ice crystal. They remain disordered. After a point, their arrangement still haphazard, the atoms seemingly grind to a halt. They might still slightly wobble in place, but you don’t see them move around again. It is as if, as they started slowing down, they got stuck – midstep in a dance for all of time as we know it.

Its molecules suspended in motion, the liquid eventually turns into an amorphous, rigid mass called glass. Everything looks perfectly still, yet if you peer closely, there is nothing perfect about it.

How is it that glass seems still enough to appear solid, but its atomic arrangement remains as random as a liquid’s?

How is it that glass seems still enough to appear solid, but its atomic arrangement remains as random as a liquid’s? That is the crux of the glass problem, and despite decades of research, there are still no clear answers. A theory of the liquid-glass transition must convincingly explain the sluggishness of its atoms and the sloppiness of its structure, but none so far have managed to do so.

“It’s probably one of those things that will never get resolved,” says Sriram Ramaswamy, Honorary Professor at the Department of Physics, IISc. “That’s my suspicion, but some, perhaps many, will disagree with me.”

This is not due to a lack of ideas; physicists have long theorised about how a liquid cools into glass. Some believe that it only depends on the atoms’ movement and is thus a purely dynamic phenomenon – as the atoms cool, they slow down to the extent that the liquid looks solid, but deep down, its structure remains stubbornly that of a liquid. Others insist that there is a hidden structural change slowing down the atoms, making it a thermodynamic phase transition – like a complex version of water turning into ice. Physicists have found evidence that supports both sides of this debate. Many even think reconciling the two sides might give us the full picture. But so far, that has been easier said than done.

“The deepest and most interesting unsolved problem in solid-state theory is probably the theory of the nature of glass and the glass transition,” wrote theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate Philip Anderson in Science in 1995. “This could be the next breakthrough in the coming decade.”

30 years later, how far have scientists come?

Facilitating flow

In the early 1900s, scientists realised that if you rapidly cool some liquids, like silica, to a temperature below their freezing point, they become “supercooled” and eventually turn into glass. As the liquid transitions, it becomes incredibly viscous – its atoms slow down by about 1,000,000,000,000,000 times.

As it transitions, the relaxation time of its atoms also changes dramatically. Picture perturbing water in which atoms are all quickly moving about and rearranging. The time that it takes for the atoms to forget the perturbation and return, or “relax” back into their original state, is the relaxation time; for water, this is about a billionth of a second. But at the glass transition temperature – around 550°C for window glass – these times stretch to hundreds of seconds, becoming so large that the atoms appear to stop rearranging altogether once glass forms.

But if you closely observe its molecular structure, the glass still “looks” exactly like the liquid it once was. All the atoms are still randomly arranged. Yet we know that glass feels nothing like a liquid – it can be both strikingly hard and frustratingly fragile.

(Illustration: Sumana Sainath)

Many aspects about the liquid-to-glass transition are unique and different from how water freezes. We learn in school that when water turns to ice, it releases energy in the form of latent heat. But no such heat escapes when liquid silica supercools to glass. No matter how fast or slow you cool down water, it will always turn to ice at 0°C at a fixed pressure. But the temperature at which a liquid turns to glass depends on how fast you cool it – usually, the faster it is cooled, the higher the temperature. Ice’s properties vary sharply from water’s, but as molten glass solidifies, its properties change smoothly instead. Even the increase in viscosity, albeit steep, is not a sharp transition.

Another peculiarity that has puzzled scientists is how glass is not at an equilibrium state

Another peculiarity that has puzzled scientists is how glass is not at an equilibrium state. Water and ice are both at equilibrium – at any given temperature and pressure, they are in their most stable state and nothing inside them will jostle them out of it. But with glass, it seems like it just got stuck somewhere on the way to its most stable state. Like its molecules want to arrange themselves neatly in the form of a crystal, but they are moving just too slowly to get there. “In this view, it’s wandering desperately forever, not settling down to the state it actually wants to be in,” says Sriram.

All these findings led some scientists to believe that the kinetics – or how the atoms slow down – is key in driving a liquid towards glass. In the 1980s, German physicist Wolfgang Goetze put forward the Mode-Coupling Theory (MCT) from this dynamics perspective.

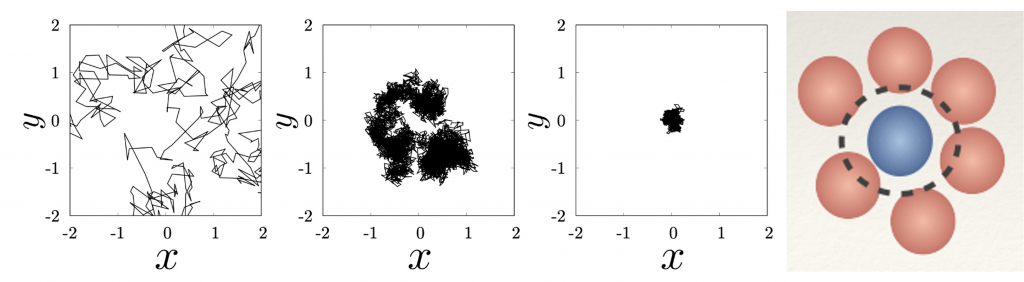

This mathematical theory predicted that the atoms of the liquid get increasingly crowded the closer you get to glass, to the extent that they become almost trapped by their neighbours. At this point, they cannot move any further, they can only wobble about in a cage formed by their own surrounding atoms. Close to the critical temperature around which glass forms, the atoms get stuck in their cages, unable to break free or “relax” back into their original state.

But that was not entirely accurate. Experiments eventually found that even beyond that temperature, glass atoms could still relax; the system had not stopped rearranging as some had hoped. The theory explained the early stages of glass formation as the atoms start slowing down, but what happens at the transition was still somewhat opaque.

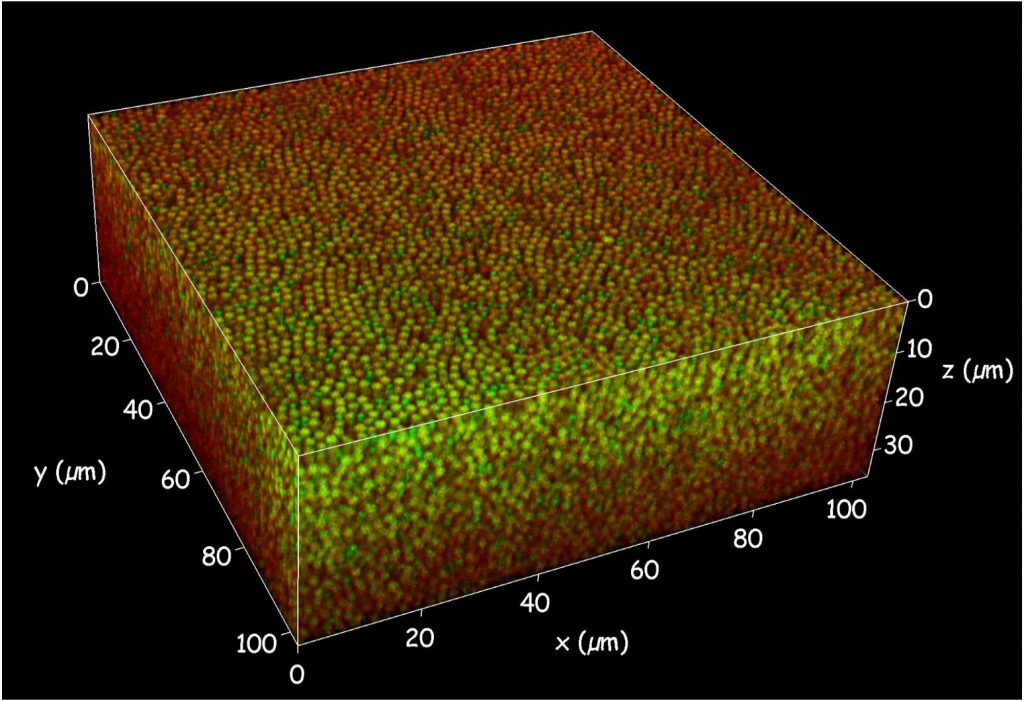

Scientists have also used colloids – microscopic particles suspended in liquids – to study glass formation. Densely packing together many colloidal particles is similar to supercooling a liquid, and because the particles are big enough in size, they are easier to visualise than assemblies of glass atoms. Using such systems, scientists have discovered “dynamic heterogeneities” in supercooled liquids – not everything is perfectly still, particles in some regions can reorganise and relax to a smaller extent as compared to other regions. As some particles relax, they help their neighbours move.

“For example, in a very, very dense crowd, not everybody gets to relax at the same time,” explains Rajesh Ganapathy, Professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research (JNCASR). “You will see 10 people next to you relaxing, then you will get some room to move, then somebody next to you will move, right? Somebody facilitated your motion.”

This led to the more recent dynamic facilitation (DF) theory, which predicted that cooperative movement in different regions could help glass atoms eventually relax, even if all the atoms seem like they are stuck in their cages. In fact, many DF theorists believe that there is no “glass transition” as such; it’s just that the likelihood of these cooperative regions appearing goes down the colder it gets. DF was able to explain some features of glass even in a “deeply supercooled” regime – when the liquid appears as still as glass.

But physicists on the thermodynamics side were not completely convinced, because DF does not say much about how or why cooperative regions would pop up in the first place.

‘The fact that [an order] is hidden is what makes it [glass transition] so much more beautiful’

Yet another conundrum is that viscosity increases in a steep yet smooth way only in what are called “strong” glasses, like silica or window glass. In some organic liquids, like o-terphenyl, the viscosity shoots up much more dramatically – almost sharply increasing as they transition to glass. Such “fragile” glasses prompted thermodynamic theorists to believe that something deeper must drive this drastic change. Could it not be that instead of particles simply slowing down, there is some inscrutable, yet increasing sense of order that instead reduces their movement? That the disorder in the system ultimately plunges to zero, tipping the deeply supercooled liquid state over to a stable, solid, glassy one?

“The fact that [an order] is hidden is what makes it [glass transition] so much more beautiful,” says Rajesh. “Because you have to really go search for it.”

Glassy metal

Despite not understanding glass well, humans have bent it to their will for millennia, with some of its oldest uses found in vessels and jewels in ancient Egypt. Today, glass is as ubiquitous as it is unique – found in the fibre optic cables that sustain the internet, in our megapixel camera lenses, and in many more devices.

Humans continue to push its boundaries as a material. In 1960, Belgian physicist Pol Duwez discovered that rapidly cooling certain metal alloys turns them into metallic glass – amorphous metals that are much more durable and energy-efficient. As they corrode less, metallic glasses can be used in biomedical devices, and some amorphous steel alloys have record-breaking resistance to deformation. However, they are tricky and expensive to make, as one needs to cool down the molten metals at a very rapid rate or prepare the alloys with extreme precision. Nevertheless, NASA has been exploring their use in lubricant-free gearboxes in space robots.

An emerging order

To understand the thermodynamic quest for order, let us go back to the familiar case of water cooling into ice – a true thermodynamic phase transition. As water freezes, its particles slide into a strictly ordered structure. “Therefore, you can define some order parameter – essentially a quantification of the degree of order in the system,” explains Rituparno Mandal, Assistant Professor at the Raman Research Institute, Bengaluru.

An order parameter helps build a thermodynamic theory to explain how water turns to ice, but during glass formation, there is no clear change in order or any significant structural change. Nevertheless, many believe that there may be some imperceptible changes that have somehow escaped their scrutiny. “The structural indicator, if it is even there, is very hard to find,” Rituparno says.

Rajesh is also interested in finding this elusive order in supercooling liquids, but he doesn’t want to get attached to either the thermodynamic or the dynamic side. “As an experimentalist, I am not supposed to be biased about what to expect,” he says. “My job is to go do the experiment and say, ‘this is what I found.’ Then we assess which theory captures the results best.”

In a 2023 PNAS paper, Rajesh and his team peered at a dense mixture of colloidal particles under a confocal microscope and realised that there is an “intermediate-range” order in the system. It is not a long-range order, with all the atoms arranged periodically like in a crystal. But it goes beyond short-range order, which is looking only at links between immediately neighbouring particles. They found that as the particles get more densely packed – like what happens when a liquid is supercooled – this intermediate structural order increases and even influences the dynamics of the particles.

Other groups have also found that there is a growing “amorphous” order in supercooling, glass-forming liquids. “In a liquid, everything moves. You can go to any part of the liquid, and all the particles will behave in roughly the same manner. In a supercooled liquid, that is not the case,” Rajesh says.

“There are regions that suddenly relax, there are regions that don’t relax for a long time. Does that have something to do with the structure? What we find, what simulations find, what experiments find, time and again, is yes.”

Another clue that supports the thermodynamic perspective is a prediction by American physicist Walter Kauzmann in 1948. He realised that if he could cool a glass-forming liquid extremely slowly beyond its freezing point, then he could “supercool” it for longer and delay its hardening into glass. He also found that the liquid’s configurational entropy – all the different configurations its atoms can assume – drops gradually as the liquid is cooled. Theoretically, if one keeps extrapolating this decrease, this entropy – a rough measure of the liquid’s “disorder” – ultimately vanishes. It drops to zero at a temperature called TKor the Kauzmann temperature, which is usually below the actual glass transition temperature.

In 1958, American scientists Julian Gibbs and Edmund DiMarzio proposed that at TK , the supercooled liquid must transition to an “ideal glass” – a state with the densest possible random arrangement of molecules. In theory, ideal glass is about as stable as a crystal.

But in reality, no one has managed to even go close to that temperature. The glass atoms slow down to such a massive extent before reaching TK that it is eventually impossible to measure any useful structural changes with experiments or simulations. Most experiments that make measurements operate in the moderate-to-deeply supercooled regimes – not where the ideal glass transition could supposedly occur. In these early stages, the structure barely changes, prompting dynamic theorists to dismiss any small variations as largely unimportant and focus only on the atoms’ motion (or lack thereof).

But thermodynamic theorists remain undeterred, insisting that scientists just haven’t cooled the liquid enough. If they do ever hit TK, there will be a payoff – a dramatic change in order will make the viscosity skyrocket and turn the liquid into ideal glass.

As scientists access newer degrees of supercooling both experimentally and in simulations, they are starting to see more drastic changes in structure, Rajesh says. “But when it comes to the ideal glass transition, we are nowhere near there,” he adds.

Some scientists think that the system simply falls out of equilibrium – gets frozen, seemingly forever, before it could ever become ideal glass. But given enough time – perhaps at the end of the universe – could it happen? “Given that nobody can wait long enough to actually see if that really happens, there is a debate about which one of the theories is correct,” says Rajesh.

“My own personal view is that there isn’t an incompatibility between these different pictures,” adds Srikanth Sastry, Professor at JNCASR. “We just don’t know how to put it all together.”

An “ideal” mirror

The melting of stained glass windows in centuries-old cathedrals is a myth that has appeared even in textbooks. Since the bottom of those glass windows is thicker than the top, it looks as if the glass has been gradually flowing all these years, suggesting that it may have been masquerading as a sluggish supercooled liquid all along.

However, in 1998, Edgar Dutra Zanotto, Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at Federal University of São Carlos, Brazil, published a calculation shattering this myth. Factoring in the viscosities of ancient and modern window glasses, Edgar showed that it is theoretically impossible for cathedral glass windows to have melted since medieval times. Glass atoms are too slow to flow in such a short time – even ancient Egyptian glasses from 3,500 years ago still look the same. In the best case, it would take 1033years. As no one can wait that long, we cannot assume that window glass is simply a slow-moving liquid.

The reason why the glass’s bottom edges are thicker is that the glassblowers of that era were unable to make completely flat panes, scientists think. They simply put the thicker edge at the bottom for stability. “For window glass to flow, it’s going to roughly take the age of the universe,” says Rajesh.

A rugged landscape

Despite the uncertainties, the allure of an alleged, albeit unattainable, temperature at which ideal glass could emerge was very attractive to theorists. In the mid-1980s, American physicists Theodore R Kirkpatrick, Devarajan “Dave” Thirumalai, and Peter Wolynes developed the random first-order transition theory (RFOT), a mathematical theory that uses an energy landscape to describe what might happen at this temperature.

Imagine a rough terrain with multiple valleys, each valley corresponding to a different, stable configuration of the liquid’s atoms. The valleys are associated with having low energy and being stable, with atoms needing extra energy to jump from one valley to another. The number of these valleys also represents the system’s configurational entropy.

Initially, the liquid’s temperature and energy are high – it can quickly flit from valley to valley, exploring various configurations. As the liquid cools, its energy drops and it becomes harder for the liquid to jump between the valleys. This causes the moving atoms to slow down, as they keep getting stuck in one of many “metastable” yet disordered states. As it cools further, the entropy decreases and the number of stable valleys reduces, but they are all as deep as ever – making it harder and harder for the cooling liquid to escape any valley it gets trapped in.

Even as one rolls about in this hypothetical landscape, we must remember that atoms slow down when glass forms – the liquid becomes so viscous that it basically stops flowing. “What does the vanishing of the entropy have to do with why the viscosity changes so rapidly?” asks Srikanth. “This is one thing that has driven the field – seeking answers to this very simple-sounding question.”

Scientists have tried to connect entropy to dynamics in RFOT – as the entropy, or the number of valleys, goes down, the atoms spend more and more time in a single valley, slowing down the whole process towards ideal glass. But more work needs to be done to bridge this gap rigorously, Srikanth says.

Ultimately, according to RFOT, at TK, this entropy will drop to zero. Only the deepest valley will remain, and the cooling liquid will freeze into a single, stable, amorphous state – ideal glass.

Italian physicist Giorgio Parisi, who won the Nobel Prize in 2021, came up with a calculation that showed that something like this could actually happen. But it only works in a scenario with infinite dimensions, not in our real 3D world.

In a system like glass, there are many atoms packed close together, each interacting with the other in uniquely different ways

In a system like glass, there are many atoms packed close together, each interacting with the other in uniquely different ways. Modelling them as an infinite dimensional system makes it slightly easier to make some assumptions, says Rituparno. “In the infinite dimensional limit, logically your number of neighbours are infinite,” he adds. “So, fluctuations play less of a role.”

Fewer dimensions means fewer surrounding atoms, and the more that each atom will be affected by its neighbours. If there are infinite neighbours, it is a tad easier to average out the effects. This gives scientists a template to work with.

“It is a good step, because now they are trying to extend that theory from infinite dimensions to finite dimensions,” says Rituparno.

Dripping over decades

Some amorphous solids flow faster than window glass, oozing out a single drop in about a decade. Pitch, or bitumen – also called asphalt – is an extremely viscous component of crude oil which looks solid at room temperature. But if you wait for a decade, you can see it flow. “[Pitch] is an intermediate between water and the window glass … between 1 second and 1033 years,” says Rituparno. In 1927, University of Queensland physics professor Thomas Parnell heated some pitch and let it cool in a sealed funnel for three years. In 1930, he cut the funnel and let the pitch drip. It took about eight years for the first drop to fall. Since then, eight more drops have fallen, with the ninth one having plopped down in 2014. This pitch drop experiment is featured in the Guinness World Records for the world’s longest-running lab experiment and won both Thomas and fellow scientist John Mainstone the 2005 Physics Ig Nobel Prize, a parody of the Nobel Prize.

The glass paradigm

From inching closer to accessing deeply supercooled regimes to understanding an energy landscape in infinite dimensions, physicists have explored the glass problem from many different lenses. But it remains hard to crack using the tools that we currently have.

Daniel Fisher, Professor of Statistical Physics at Stanford University, says that the fundamental problem – how some glass-forming liquids seem to slow down so much in a narrow temperature range – remains unsolved. “A lot of the theory has focused on the initial [slowing down] part, rather than what it looks like once [the viscosity] is sailing up dramatically,” he says.

“Constructing a full-fledged theory for the second part is harder than for the first part,” says Giulio Biroli, Professor of Theoretical Physics at École Normale Supérieure, Paris. “It’s a really new phenomenon, so one cannot take a block of theory that was already developed for something else and change it a little bit,” he adds. And any fresh theoretical ideas are hard to test because of the supremely slow dynamics. “If there was a breakthrough in the way we simulate or experimentally probe glasses, this could be very beneficial to develop more theory,” says Giulio.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) could be one way out. Using machine learning, one could potentially simulate the viscosity increasing dramatically, Daniel says, by building simple, predictive models that successively capture the sluggish dynamics over much longer timescales. Giulio, who is currently testing the use of AI in speeding up simulations of glassy systems, also thinks this might help. But for the moment, we don’t know whether it works for sure, he says.

An “ideal” mirror

The almost-perfect mirrors of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) – twin facilities in the USA used to detect gravitational waves from the distant universe – are made entirely of glass. Our bathroom mirrors consist of metals that reflect light, covered by a glass shield. LIGO’s laser would cook any metal it lands on, hence its mirrors are made up of 36 layers of carefully crafted glass. Glass usually allows most light to pass through and only reflects a small amount. In LIGO’s mirrors, each layer reflects a bit of light – and the rays all combine in a way that the mirror is 99.9999% reflective. The slight imperfection arises from how glass atoms can sometimes switch between two different configurations, which minutely affects how the laser light travels between the mirrors. For a system set up to measure gravitational waves the size of about a thousandth of an atom, this imperfection is an issue. It turns out that ideal glass may offer a solution. While trying to understand the glass transition from a thermodynamic perspective, physicists have now developed an ideal glass-like substance – “ultra-stable” silicon glass. With fewer imperfections, it may be more ideal for some layers in LIGO’s mirrors.

Nevertheless, grappling with the peculiar yet profound glass problem has allowed scientists to explore other physical and even biological puzzles. The study of active glass is an example. “In an active glass, you have a dense suspension of active particles,” says Prerna Sharma, Associate Professor in the Department of Physics, IISc. “And because it’s so crowded, [the system] is not going to rearrange very fast; the dynamics are going to slow down.”

Instead of lifeless particles that only vibrate when heated, tightly-packed active particles can propel themselves using their own energy and settle into glassy systems of their own. Physicists working on active glasses have shed light on some bizarre biological behaviours, like how densely-packed bacteria could lead to bacterial glass or how, by changing its own shape, a single cell can squeeze its way out of a tightly packed tissue layer (think metastatic cancer).

Even the concept of an energy landscape has been applied in different contexts, like figuring out how proteins fold, how memory might form, and how machines could learn.

“The glass problem is a paradigm of how complex the behaviour of a physical system will become when there is the possibility of multiple stable states,” says Srikanth. “So, even if you don’t have a complete understanding, whatever understanding you have can take you far.”

(Edited by Ranjini Raghunath)