The need for archives in academic institutions

In a pivotal scene in the sensational Christopher Nolan film, Oppenheimer, the protagonist, J Robert Oppenheimer, meets Danish physicist Niels Bohr while struggling with his research at Cambridge University in the early 1920s. Bohr urges Oppenheimer to move to Germany and study under the famed physicist and mathematician Max Born, a move that marked a turning point in Oppenheimer’s life and the eventual development of the atom bomb. Many people know about Born’s contributions to quantum mechanics, and of his role in inspiring leading scientists of that time, such as Oppenheimer and Werner Heisenberg. But how many know about the time he spent at IISc, a short six months as Reader in Theoretical Physics?

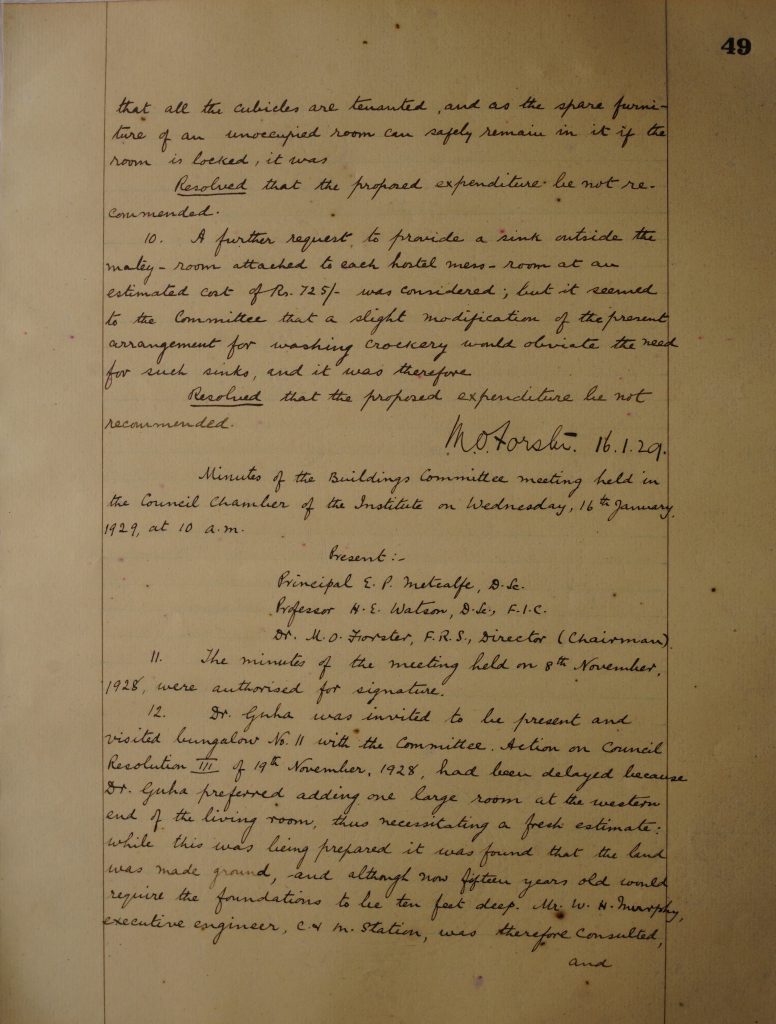

Step into the archives of IISc, and you will find letters exchanged between CV Raman, the then Director of the Institute, and Born. These letters don’t just outline Raman’s job offer to Born, but also reveal the former’s ambition to expand the Institute’s scientific horizons. Born, a Jewish scientist who had to leave Germany because of the Nazis, accepted Raman’s offer. But Born’s visit to IISc came at a time of turmoil. Raman and some of the Institute’s faculty members were at loggerheads, their disagreement escalating when the former attempted to secure a permanent position for Born. The conflict that unfolded – recorded in bits and pieces in minutes of the Institute’s Council and Senate meetings from 1936 and 1937 – eventually led to Born’s departure from IISc and Raman resigning from his role as the Director in 1937. It is only from piecing together information in various letters, Annual Reports, Council minutes and other documents, painstakingly preserved for over a century, that we are able to tell such stories from the Institute’s past – proof of how valuable archiving can be.

An archive is a storehouse of wisdom, holding inside its quiet rooms a treasure trove of knowledge that can help shape our understanding of the world. Archives function akin to a time-travel device, enabling us to journey backwards and peek into past lives and events.

An archive functioning within an academic institution holds a vast collection of works produced by faculty members, staff, and students. Its collections usually go beyond scholarly articles such as journal publications, and include documents containing the written words of its researchers and administrators that provide snapshots of academic and student life, and details about the institution’s evolution. These include letters, reports, meeting minutes, old photographs of significant events, notes, and memos of people joining and leaving the institution. One may find a mix of documents belonging to or about both well-known and lesser-known individuals. Each institutional repository has a different focus. Materials stored in the archives are both physical and digital – housed in servers and online repositories.

Archives function akin to a time-travel device, enabling us to journey backwards and peek into past lives and events

At the archives of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad (IIMA), for example, among the many valuable documents are a series of letters and notes from the office of Harry L Hansen, a former Director of Harvard Business School’s Division of International Programmes, who spent considerable time at IIMA and played a key role in advising its faculty members in its formative years, explains Abhishek Mishra, archivist at IIMA. Other documents include letters, notes, committee meeting records, reports, building plans, curriculum details, policies, staff information, and administrative papers. The IIMA archives also houses special collections, such as oral history recordings related to the history of computing and advertising in India, documents related to the history of Indian management institutes, and directories of stock companies and investors from the early 1900s to 1950s.

Institutional archives, such as the ones at IISc and IIMA, are different from public archives like the National Archives in New Delhi. Public archives store government-related documents, material related to different communities, and culturally significant artefacts. On the other hand, the collections in institutional archives are “more flexible and organic,” observes Anjali J, archivist at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS), Bangalore. Materials in public archives are curated and categorised based on their importance. Not all original pieces are necessarily collected; archivists choose the most vital and representative ones for preservation, she adds.

Institutional archives are first and foremost committed to their parent institution, prioritising the collection of materials unique to that institution’s history. They are usually located within or near it, symbolising their strong connection with the institution’s identity. They are often supported by the parent institution, but external agencies, philanthropists and alumni also contribute funds to support such archives.

Some institutional archives have gone beyond just preserving their parent institute’s history. An example is the Archives at NCBS, which has now evolved into a public repository for contemporary science, housing special collections like that of entomologist Leslie Coleman, oral history recordings of Indian scientists, and a large collection of papers and materials on MS Swaminathan, considered the father of India’s Green Revolution. Institutional archives also collaborate with other organisations and companies to curate and exhibit their material. “The response from our wide array of stakeholders and users guided us to conduct exhibitions, and collaborate with the Ministry of Culture,” says Abhishek. “In the long run, we aim to be a business history research hub.”

Preserving IISc’s history

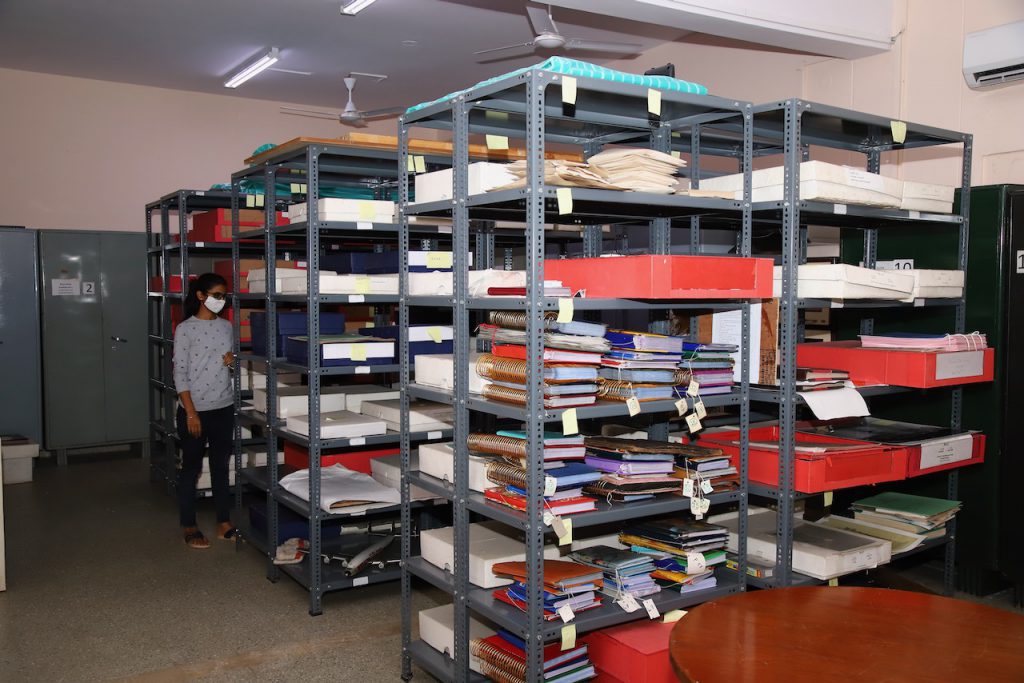

As one of the first institutions in the country to focus solely on advanced scientific research and education, IISc has remained one of the main characters in the still unfolding story of Indian science. Preserving its historical material can not only help safeguard its legacy but also provide lessons and learnings for the Institute’s advancement. The IISc Archives, housed within the Office of Communications (OoC), is the custodian of most of the Institute’s historical documents sourced from various academic and non-academic departments – papers, reports, photographs and artefacts that capture various moments in its history.

Preserving its historical material can not only help safeguard its legacy but also provide lessons and learnings for the Institute’s advancement

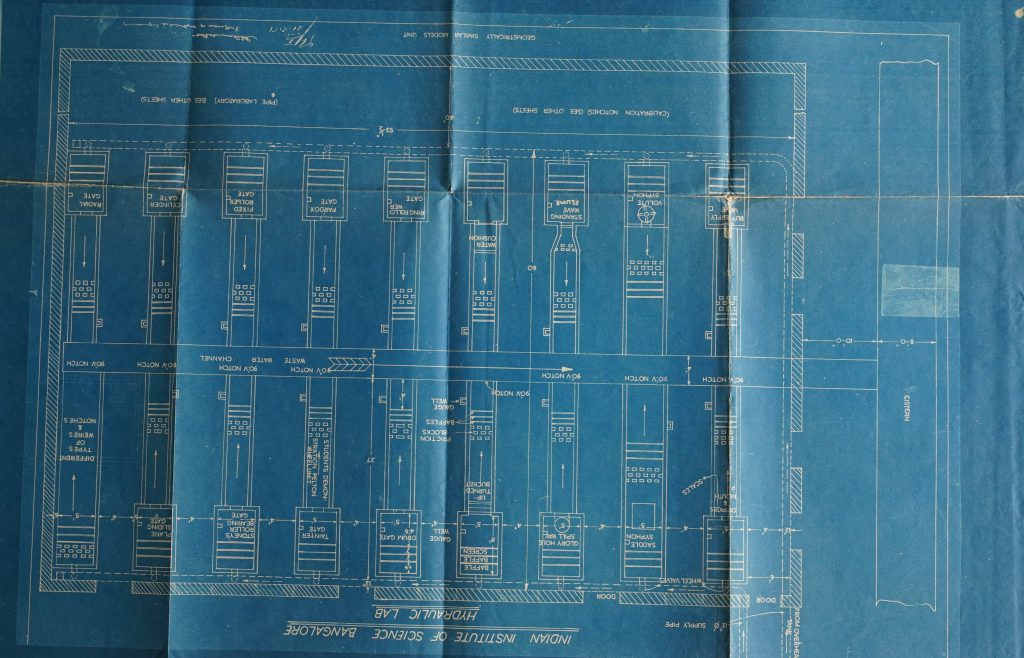

As an in-house archive, its collections are somewhat unique. For instance, it houses a rare collection of blueprints of labs, buildings and research equipment. One of these is a blueprint showing the structure of a liquid-liquid extraction column dated 13 November 1957. “Blueprints were used to get multiple copies from a single drawing. When making them, the drawing is done on a transparent sheet with black ink or pencil. This sheet is placed under another sheet treated with ammonium citrate and exposed to sunlight for a certain time. The parts exposed to light turn blue, while unexposed parts under the ink remain the same,” explains Sindhu Nagaraja, a conservationist who consults at the IISc Archives. There are also blueprints of the construction plan for the Primate Research Laboratory, dated 1975, and maps of faculty housing colonies printed using an ammonium printing technique that uses a UV machine instead of sunlight. These were some of the early methods used to make copies of building designs and lab apparatus. “The signatures and notes inside these materials add an extra layer of intrigue to the collection,” she adds.

At the IISc Archives, there are also detailed reports from the years 1922 to 1936 that were written by hand, and letters that used iron gall ink – a mixture of iron and resin extracted from plant seed that initially appears light brown, but turns darker as it oxidises over time. Such ink is no longer popular.

Sindhu suggests that even if the content in the archival material is scientific and not easy to understand – for example, drawings of chemical structures, research papers or lecture notes – one can still appreciate their historical value. Archival material also contains a wealth of information hidden inside. For instance, a photo of a scientist from a certain time, say the 1990s, isn’t just about them. The photo also tells us about the photography methods and equipment used at that time, the studios where the photos were taken, and the names of the photographers of that era. Even background details, like the labs the scientists worked in or the buildings they stood in front of, tell stories, adding social context to their scientific activities. The IISc Archives also house mementos of kinship among scientists. For instance, in 1961, the staff and students of the Department of Inorganic and Physical Chemistry gave a specially designed silver scroll to one of their retiring professors, KR Krishnaswami. This scroll and a moving letter they penned to him are now kept in the IISc Archives.

When it comes to conserving such materials, there are several questions. First, how do you choose what materials to keep? When managing materials from an institution, there’s usually a structure to think about that is specific to its setup. At IISc, there’s a hierarchical structure that includes the Court and Council, the Director, and six academic Divisions under various Deans (previously Chairs), and administrative sections under the Registrar. The Archives hold documents from these different levels, so there’s a need to organise and preserve them in a structured way.

Sindhu explains that one of the many challenges a conservator may face is in prioritising the materials to be conserved. In such cases, one may need to make decisions about which elements to preserve and which ones to store separately to ensure their safety. Discussions with other experts and stakeholders are essential to make informed decisions about conserving damaged materials, which requires careful consideration of the urgency and importance of each item. Some treatments, like encapsulation or fumigation, can take significant time.

Documenting all the details and procedures undertaken during the conservation process is also crucial. Proper documentation helps in understanding the condition of the materials before and after conservation, as well as any significant alterations or separations made. For instance, if the material was exposed to fire, water seepage or extreme change of weather, any resulting marks left on them will be recorded in the condition report. This will provide a better understanding of the history of how the materials were handled.

Every archive also needs to keep in mind two principles of archiving – the principle of provenance and the principle of original order. The principle of provenance focuses on the history of ownership, how the records were created, who their owner is, what their purpose was, and how the material changed hands over time. The principle of the sanctity of the original order means that records should be kept in the same order that they were originally organised.

But a general problem in India, Anjali points out, is that there is no strong archiving culture, even in households. “For instance, during the Aadi month in some of the southern states or other festivals, items are discarded to make way for new ones, which symbolises a fresh start,” she explains. “From our cultural perspective, archiving day-to-day amenities is often perceived as a niche concept, as many Indians tend to dispose of things rather than preserve them.”

The need for preserving history

In addition to the more routine considerations like prioritising and choosing materials for conservation, there are more significant questions that the archive must address. First, it is the responsibility of the archive to establish a significant level of trust with not only people who donate to it but also people who need to access it. In countries like India, some experts believe that there is a prevalent sense of distrust towards governmental institutions. An archive should strive to not only faithfully preserve the materials, but also safeguard their use, says Anjali.

The resources and information in archives are but small fragments in a broader historical context

Second, it is important to understand that archiving is not solely about highlighting the merits and achievements of the institute. From their archives, institutions can access a wealth of information about past decisions, successes, and failures, and learn from them, Anjali adds. For instance, in 1943, IISc decided to construct a new building that included a dining hall and auditorium. This new facility was intended to provide a single dining area for all students, replacing the nine separate eating spaces that existed based on students’ eating preferences – which some argued were along the lines of caste division. The IISc archives houses a letter from 12 March 1943, written by a student named M Jagannadha Rao, who opposed the plan for a common dining hall and even went on a hunger strike to protest it. Despite resistance, the dining hall was eventually built. These letters show how the Institute grappled with a social problem at that time, and the steps it took to address it, which may also have lessons for dealing with similar situations in the present and future.

The resources and information in archives are but small fragments in a broader historical context. With the current information boom and advances in technology, it becomes crucial for us to accurately record facts for posterity. As Debra Steidel Wall, Deputy Archivist at the National Archives and Records Administration, USA, points out in the magazine Archival Outlook: “Now more than ever, in our age of information overload, misinformation, and disinformation, access to and an understanding of authentic documents is powerful and necessary.