Manju Bansal, INSA Senior Scientist at the Molecular Biophysics Unit (MBU), joined the department in 1972 after completing her BSc and MSc from Osmania University, Hyderabad. She completed her PhD under GN Ramachandran, working with him on theoretical modelling of the triple helical structure of collagen. On the occasion of his birth centenary in 2022 – which also marks 50 years of her time at IISc – she describes what it was like to work with the renowned biophysicist and how it influenced her career.

When I was doing my Master’s in Physics at Osmania University, biophysics was an unknown field. But in 1970, the Nobel Prize was given to three scientists [described as biophysicists] for their work on synaptic transmission in nerves. The news even made it to the local newspapers, and sparked my interest. We had heard that the University of Madras had a good biophysics department, but Prof R Srinivasan, who came from there to conduct our practical exams, advised me to apply to IISc for my PhD because Prof GN Ramachandran (GNR) had just moved here.

At that time, due to the Telangana agitations, our exams were routinely delayed. The day I got my interview call from IISc was the day that I had my last practical exam. When I asked them to postpone the interview, initially the authorities said no, but a few days later I received a telegram asking me to appear two days later. I finished my exam, and rushed over from Hyderabad to Bangalore – the first time I had travelled alone. At the lecture hall complex in IISc, where the Molecular Biophysics Unit (MBU) was housed, there was just one guy in the office and no other interviewees. He told me that the interviews were over, but as Prof GNR wanted to interview me, he had held back the interviewers who had come from Madras, for one more day.

That made me very nervous. The interview was held in Prof GNR’s office, right next to his working table. He was very tall, and had an impressive personality. One of the first things he said was, “We don’t want to find out what you don’t know. We want to know what you know. You tell us the topics that you feel comfortable with.” I rattled off a few topics, and the interview went on for one and a half hours. Apart from Prof GNR, there was Prof KRK Easwaran, another faculty member at MBU, and Prof C Ramakrishnan and Prof V Sasisekharan from the University of Madras [they later joined MBU]. After the interview, they told me that as long as I received a first class in my MSc exam, I could join the department. My results were only declared in August and I landed at IISc on 10 August 1972.

Modelling collagen using an IBM 360

There were five students in our batch, and we were the second batch in the department. Two of the students were already associated with faculty members who had come from Madras. Three of us were new. The other two were also assigned research areas and guides, but I was initially left high and dry, and just asked to do course work.

In September, Prof GNR returned from his trip abroad – he had an NIH fellowship at the University of Chicago and used to travel there every year – and I was told that I would be working with him. The other students scared me. One of them said, “You won’t be able to work with Prof GNR; he’s never had a girl student working with him because whoever joined left [before completion].” So, I was quite nervous when meeting him for the first time as my prospective PhD guide.

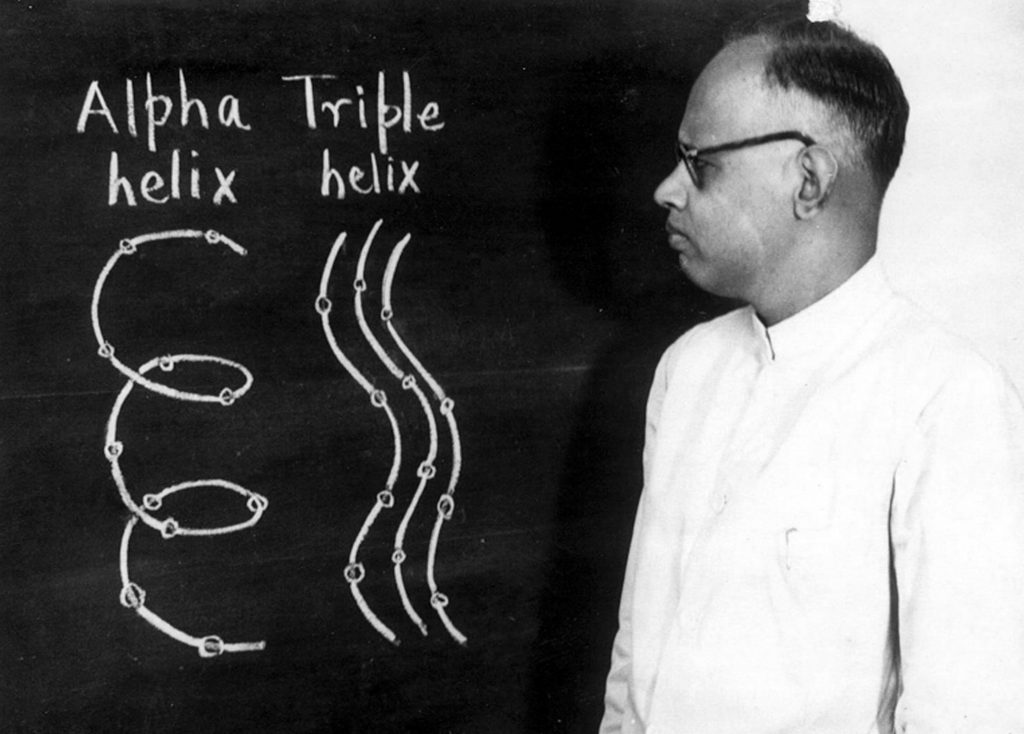

By then, I had gathered that one of his major contributions (described in two Nature articles in 1954 and 1955) was the triple helical coiled coil structure of collagen. There was a Visiting Professor from the USA (RS Bhatnagar) with whom he was planning to synthesise some modified tripeptides and study their effect on collagen structure. “We don’t have much experimental data, but you can do the modelling,” he told me.

At that time, we hadn’t seen a computer, and I had zero programming skills. There was an IBM 360 in the Computer Centre which had less compute power than our cell phones now. Prof GNR had about 20 minutes of allotted time on the computer at midnight, and every working day, I would go to the computer centre at midnight to use those 20 minutes, which had to be shared with my senior, Ashok Kolaskar.

The problem I was given was this: In the collagen structure, there is an amino acid called hydroxyproline, a modified form of proline, which is rarely present in other proteins. Even in collagen, it is incorporated into the polypeptide chain first as proline, which is then hydroxylated by enzymes. Prof GNR told me that they knew from experimental data that hydroxyproline seems to stabilise the collagen structure. They had also guessed that it probably needs water molecules for stability. But if the proline is not hydroxylated, collagen doesn’t form the triple helical structure; it disintegrates because the melting temperature is low. And they didn’t know why this was happening.

He installed red and green lights in front of his room. You were not supposed to enter if the red light was on. His secretary would call you and only then could you walk in

I set about working on this problem. There were not too many papers for us to refer to. Luckily, IISc has always had a good library, so the old Nature papers that Prof GNR and others had published were available. But writing a program to generate the triple helical structure from the published tripeptide coordinates was tough. And Prof GNR wasn’t a person into whose office you could just walk in and clarify doubts. Even though he didn’t have them at the time, he subsequently installed red and green lights in front of his room. You were not supposed to enter if the red light was on. His secretary would call you and only then could you walk in. If we had some results to show, we had to go through his secretary to meet him. This experience influenced me to be a lot more approachable with my own students, and have an open door policy. Fortunately for me, Prof Ramakrishnan, who incidentally had worked with Prof GNR on the Ramachandran map, was a programming expert and very generous with his time, and helped me a lot in those early days.

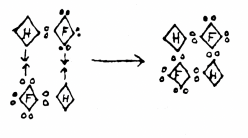

I still think it was luck, but what I did find was that although hydroxyproline cannot form a direct inter-chain hydrogen bond, one of the water molecules linking two chains of the triple helix can, with some manipulation, form an additional hydrogen bond. The OH group of the hydroxyproline acts as an acceptor from the water molecule, and the hydrogen atom of the OH group juts out, and is thus able to form a hydrogen bond between one triple helix and a neighbouring triple helix. This led us to propose a possible role for hydroxyproline in stabilising the collagen structure.

I started the work in October and by next January, Prof GNR felt that it was time to write and send a manuscript for publication. This worried me since Prof GNR would sometimes throw away papers if even a comma or full stop was out of place. With MBU being located in the lecture hall complex, this would create a scene because everybody around would see it. When one walked into the mess after that, random students would say something like, “Who got it today?” I think one of the reasons I survived with Prof GNR was that my English was good.

We sent the paper out. Around that time, the Biochemical Society at IISc had arranged a two-day picnic to Ooty for which I had joined, and that was when the manuscript came back for some small revision. When I returned, he was a little upset that I was not there the day the paper had come back. I remember that in 1974 also, when my brother got married and my mother had back surgery, I had to take leave twice. His immediate reaction each time was negative. Then, the next day he would come and say, “Ok, go.” So, working with him was a bit of a roller coaster ride. But I was fortunate to be able to publish a paper with him in just six months.

That paper, published in the journal Biochimica et Biophysica Acta in 1973, proposed a hypothesis on the role of hydroxyproline, and even though it was a theoretical paper, because he was the main author and it seemed to explain the experimental data well, it got cited quite a few times. Interestingly, 25 years later, when the crystal structure of a collagen-related oligopeptide was solved, the researchers found exactly the same kind of hydrogen bond formation we had theorised, and they were nice enough to acknowledge our contribution.

Graduating with a bit of drama

When I see my students now, most of them seem to need much more guidance, despite large amounts of information being available at the click of a button. But at that time, we had to somehow manage on our own, particularly since Prof GNR was away a lot of the time, and had fixed hours during the time he was here. We even joked that we did better work because of that.

Prof GNR didn’t teach a regular course but used to give special lectures twice a week spread over two or three months. He would give us tough assignments. In those days, there was no internet, no biophysics or structural biology textbooks, and journals arrived three months after publication by sea mail. You really had to apply your mind. Until recently, I was saving my assignments in which he had written “very good” or something similar.

Most people were scared of Prof GNR. He was very intense about his work. After having worked with Sir CV Raman, and due to his own exceptional intellectual abilities, he probably felt frustrated because none of us could reach anywhere near his level. Sometimes he was nice too, but you couldn’t predict how his mood would be. One day he might be angry with you, but the next day, although he couldn’t bring himself to apologise, he would somehow convey his feelings. The joke was that his wife probably scolded him about it. Recently, in a documentary that IISER Pune produced about his life, Prof GNR’s son spoke about how his father probably had bipolar disorder. It wasn’t a well understood disorder then, and we didn’t know he had it. But in hindsight, it explained a lot.

In 1976, by the time I submitted my thesis, I already had five or six papers published. He didn’t even put his name in two of them, saying that he was not here when I did the work. In that way, he was very honest and ethical.

However, there was a bit of drama before I graduated. When I gave him the final draft of my thesis, even though most of it had already been published, he said, “I don’t know; it doesn’t seem quite right. Why don’t you consult Prof Ramakrishnan?”

Now while Prof Ramakrishnan was extremely nice and helpful – I had published two papers with him – he was very slow, hence I felt that if I handed the draft to him for approval, it would considerably delay my thesis submission. So, I asked Prof GNR if he could just indicate what was wrong. He said, “I don’t know what is wrong, but I will know when it is right.” I was stunned by this reply.

Not knowing how to move forward, I went to meet Prof Sasisekharan, the Department Chair at that time, and explained that I did not know what corrections to make in my thesis write-up, but if Prof Ramakrishnan had to go through all my work, my graduation would be delayed by at least six months. The scholarship we used to get was Rs 250-300 per month and was only valid for four years. Since Prof Sasisekharan had also done his PhD with Prof GNR and knew him well from his Madras days, he advised me, “You just go to the hostel and don’t come to the department for two or three days. He will then call you.”

And that’s exactly what happened. After a few days, his secretary rang up and said Prof GNR wanted to speak to me. When I met him, he said, “Give the draft write-up to me once again.” The next day itself, he called me again and said, “It seems alright. I think you can submit it.” While delighted at this sudden turnaround, until I got my reports, I was very tense about what the referees would have to say. Fortunately, everything went well. One of the pleasant memories I have from this time is when his wife – a wonderful woman although we had limited interactions with her – called me and congratulated me. She said, “I am so glad that my husband has at least one girl student who has completed her PhD with him.”

Keeping in touch after PhD

Interestingly, after my graduation, Prof GNR and I had a very good relationship. He moved away from MBU in 1977-78, but later, when he was writing articles on mathematical philosophy, he would sometimes ask me to proofread them. A great compliment indeed! I also learned from others that whenever he gave lectures, he hyped up my work quite a bit and gave me a lot of credit. My husband, who also did his PhD at IISc, says that he heard Prof GNR speak once, and that he explained my work much better than I could. Even when I applied for a faculty position at MBU, he strongly recommended my case.

He made us think and question dogmas. That has helped me a lot in my own career

One of the things Prof GNR used to tell us was that in scientific research, we had to think differently, and take up problems that others were not pursuing, rather than doing “me too” type of research. He would also advise us not to accept everything that is published as gospel truth. He made us think and question dogmas. That has helped me a lot in my own career.

After studying proteins during my PhD, I switched to nucleic acids while working with Prof Sasisekharan, who was studying left-handed DNA – at that time, it was considered heresy to talk about anything other than Watson-Crick’s right-handed double helical structure. I became interested in that, and continued in MBU for four years after my PhD. Subsequently I went to Germany on an Alexander von Humboldt fellowship for a year and worked on filamentous phage structures. On returning to MBU as a faculty member, my first student was a legacy from Prof GNR and worked on peptides, but simultaneously my group began exploring the sequence dependent variation as seen in oligonucleotide crystal structures, as against Watson-Crick’s uniform double helix model for DNA. In 1988, there was a workshop at Cambridge on recent advances in nucleic acid structures, and Prof Sasisekharan, who was invited, decided at last minute not to attend. He suggested my name to the organisers, so I went, paying for the trip out of my own pocket (incidentally the air ticket cost me more than a month’s salary), because there was no time to raise funds. But attending this meeting was extremely useful and led to me becoming a recognised member of the international community working on the variability of nucleic acid structures, and afterwards, our work on the sequence-dependent local geometry of nucleic acids and its biological implications has been widely accepted. I still give a lot of credit to Prof GNR for giving me the courage to explore new areas in my scientific research.

For his work on the Ramachandran map and on the collagen triple helical structure, Prof GNR was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1977. However, he didn’t get his due recognition in India; he was not even awarded a Padma Shri. It was indeed sad that he withdrew from active research when he was only 56 years old, when he could have contributed so much more. Maybe because of health issues, he didn’t mentor any students after that, although he wrote some interesting monographs on mathematical philosophy.

In 2013, to commemorate 50 years of the publication of the Ramachandran map, we organised a major conference at MBU. About 700 people attended, including 40 scientists from abroad, even though we didn’t pay travel assistance to anybody. Most participants felt that it was a long overdue recognition and tribute to Prof GNR’s contributions` to modern structural biology.

After retirement, he initially settled down in Malleswaram. When one of his sons returned from the USA to work at the Institute of Plasma Research in Gandhinagar, Gujarat, Prof GNR and his wife moved there. Then, after his wife passed away, and his son shifted to Chennai, he moved again. In January 2001, I happened to go to Chennai for a meeting at the University of Madras, in his parent department, and I asked one of the professors, Prof N Yathindra, to arrange a meeting with him. I knew that Prof GNR’s health was not great and that he was living alone at an assisted elders’ home. But when I met him, he was mentally still very alert.

At that time, I had done some work with my student on C-H…O hydrogen bonds which are not common. In fact, Prof GNR was one of the first people who had proposed C-H…O bonds for polyglycine-like structures. I realised that even though DNA was not his forte, this was something fundamental, and that he would like to know how C-H…O hydrogen bonds form in nucleic acids, especially at certain sequences where tracts of adenines and thymine nucleotides occur. He was very excited and immediately came out with one or two ideas for what we could do next.

That was the last time I saw him because, in April, he passed away. I was glad that I had at least gone and seen him just three months before he passed away.

Prof GNR appreciated good science. He moulded us into good scientists. In the long term, I feel that I benefitted immensely by just being associated with him. At a recent meeting that I attended of the Protein Data Bank advisory board, one of the co-panellists I met is a professor at Johns Hopkins University. Over breakfast, it came up that I had worked with Prof GNR for my doctoral thesis work. She became quite excited and exclaimed, “Oh, you are GNR’s student? I present his work in my class all the time and never had the opportunity to meet him.” And then she pulled out her mobile, took my photo and said that she would share it with her students to show that she had met the student who had worked with Prof GNR on collagen structure. I don’t think I need to say anything more to highlight how much Prof GNR’s work is appreciated by the scientific community and he is often considered as somebody who is better known than some of the contemporary Nobel laureates. I was indeed fortunate to have been mentored by a genius, at the nascent stage of my scientific journey.

As told to Ranjini Raghunath