NoteBook Drive, a volunteer effort, has been running strong for nearly 20 years

(Photo courtesy: NBD volunteers)

In an otherwise silent campus, a typical Sunday sees a bustling crowd near the dining halls of IISc, with students unwinding after the week’s hectic work schedule. But what caught my eyes during one such weekend of my first year was a flurry of activity in a small space tucked away near the student housing and dining halls – a blackboard, a few school kids brimming with enthusiasm and curiosity, and a couple of graduate students. My first thought was, “Why school on a Sunday?” But the kids seemed eager to attend these extra classes apart from regular school on weekdays. The sessions were part of a mentorship programme, just one of many initiatives under the vast umbrella called ‘NoteBook Drive’, popularly known as NBD.

NoteBook Drive, an initiative run entirely by the student community at IISc, has been active for 19 years now, spreading its wings across more than 30 schools in and around Bangalore. In 2002, a few graduate students first started collecting donations and distributing notebooks in the government-run primary school on the IISc campus. This slowly grew into a massive network of volunteers coming together and building myriad initiatives under the banner of NBD. Their primary goal is to promote quality education in schools with students from lower socio-economic backgrounds, and give them an equal chance to dream big. Over a span of two decades, they have been able to touch the lives of more than 5,500 students in Bangalore and nearby rural areas.

India boasts of having the highest population of young people under the age of 29, and education is a constitutional right as well as an indispensable part of their development. Social rights activist Nelson Mandela once said, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” It is the first step in empowering people to develop critical thinking and contribute to making the world a better place. However, due to glaring gaps in socio-economic conditions in India, very few children have the privilege of even access to education, let alone quality education.

Very few children have the privilege of access to education, let alone quality education

Even though India has many government-run schools, most of them are in a pitiable condition, lacking funds for infrastructure and teachers. This puts the children from economically weaker backgrounds at a considerable disadvantage and can set them back for another generation.

Pankaj Jain, a former PhD student from the Molecular Biophysics Unit and one of the former volunteers who still participates in a few activities of NBD, recalls how his first visit to a government-run school brought him face-to-face with this stark reality. “I was back in the hostel room … and I remember crying for a while. Most of us don’t come from those backgrounds, and this is like a reality check at the grassroots level. We generally blame kids for not being attentive in class, but we don’t know the background. There is so much baggage owing to their social conditions: sickness, poverty, domestic abuse, alcoholism and many more.”

Nurturing young minds

During the first few years of NBD, the volunteers mainly focused on distributing books and stationery to randomly chosen schools in Bangalore and nearby rural areas. Then, they started activities like scholarship initiatives, mentorship programmes, Children’s Day celebrations, science fairs, robotics and computer training, classes on English communication, career guidance, museum visits, ‘Art and Literary day’ and many more.

(Photo courtesy: NBD volunteers)

With activities spread throughout the year, the NBD team keeps soliciting students at IISc to volunteer with whatever help they can provide. The team raises funds every year, with the maximum share of money flowing in from the generous contributions of the student community. Additionally, they receive some monetary help from the IISc Alumni Association of North America (IISc AANA). The money raised goes towards funding the notebooks, stationery, sports kits and so on, for thousands of students.

Vikas Arora, a volunteer and a PhD student at the Department of Physics, says, “The government provides textbooks and uniforms, but not notebooks and stationery. We try to fill the gap. We conduct a survey among teachers and the administration about the resources they need in each school. Following this, we place the orders with our long-time vendors and physically go to more than 30 schools to distribute the things. All this involves a lot of coordination, planning, and effort.” He pauses and smiles to add, “But it feels completely worth it when the child has a new notebook in hand and smiles ecstatically, flipping and sniffing through the fresh pages.”

A significant chunk of the funds also goes into scholarship initiatives for students in the 11th and 12th standard. A group of volunteers conducts surveys across many schools in nearby villages and slums of Bangalore every year. They try to identify students in dire need of monetary help in finishing their higher secondary schooling. The surveys are carried out by visiting the students’ homes and families and allocating funds to as many students as possible. Vikas recalls his experience with one such survey recently. “I went to a remote village nearby which lacked even proper roads. A girl student there could not pay the fees for her 12th standard year, with her father in deep debt due to job loss during the COVID-19 pandemic. They are in such dire need. How can they ever be on equal footing when competing in the national-level exams after secondary schooling?” He explains further how the student’s gender exacerbates the issue, with parents trying to marry off the girl child as young as 15 years old because they have no way to fund her education.

A significant chunk of the funds also goes into scholarship initiatives for students in the 11th and 12th standard

“That is why scholarships help,” adds Pankaj. “Scholarships have made a big difference where sometimes we were able to take the kids out of their homes and place them in hostels.” Karim Saab was a brilliant student and the school topper. Still, his brother wasn’t ready to let him continue his studies as he needed help with running his roadside eatery stall. The NBD team helped Karim move out of his home and placed him in a hostel in Tumkur. He finished a diploma in electronics and secured a job in a company. Karim says, “NBD not only helped me for studies (sic) but also took care of me when my health was poor. This is something I will never forget.” Numerous such stories are a silver lining in an otherwise murky situation.

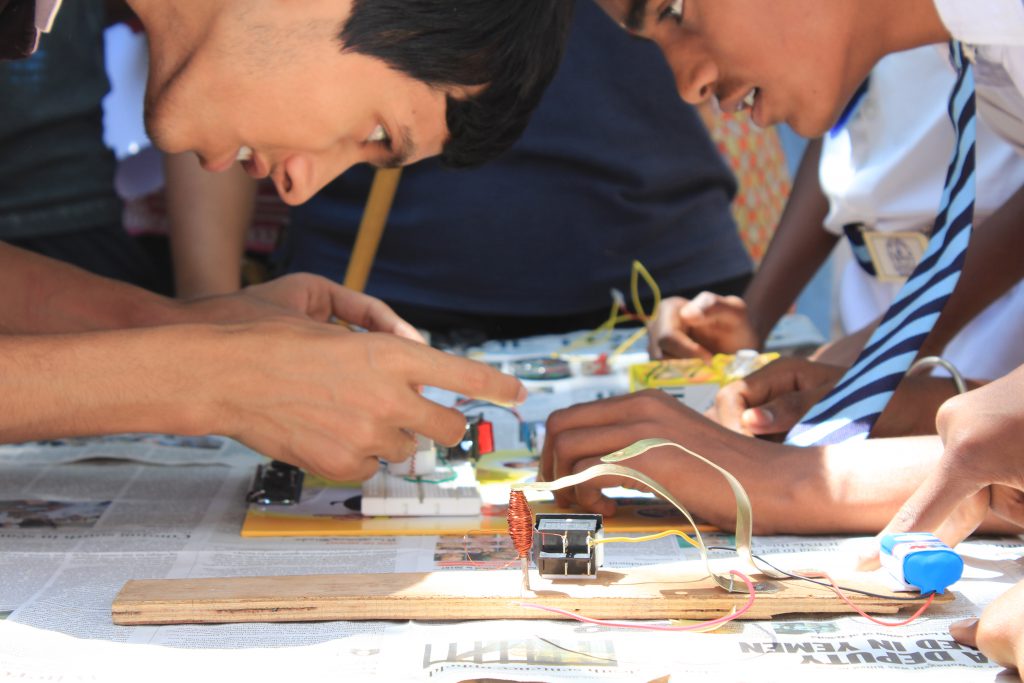

Apart from providing monetary help, the volunteers also spend time with students mentoring them in various subjects. Every weekend for six months, the volunteers teach science, mathematics and English to the students. They give them hands-on experience with science experiments and brainstorm creative and innovative ideas for small science projects. Afterwards, the students demonstrate their ideas in a science fair set up at IISc.

Another addition is computer and robotics training. Although a few schools have computer labs and robotics kits supplied by the government, the students lack mentors to guide them in using the resources, and this is where the NBD volunteers lend a helping hand. “Mentorship is fun. You get to relive your childhood,” says Gokul Krishna, an undergraduate student. “We took everything our teachers said for granted and never questioned them, but now those questions are raised to you by these kids.” He recalls an amusing incident while he was teaching science to primary school children. “When asked how a tree absorbs water, a student shot back confidently, ‘When it rains, the water from the ground evaporates, and the leaves catch hold of it.’” Instead of correcting the students, Gokul prods them into thinking creatively and arriving at the answer. Most volunteers follow this way of teaching. Alongside the mentoring programmes, the NBD volunteers also conduct career guidance sessions for the students at the secondary school level. They help students recognise their interests and skills to match them with a possible career option.

(Photo courtesy: NBD volunteers)

While these serious activities form the crux of NBD activities, most volunteers agree unanimously that the Children’s Day celebration is their favourite of all. They get around 200 volunteers from IISc to visit 25-30 schools and plan a ‘fun day’ for the kids. Various activities like sports, dance, origami, art, clay modelling, acting and singing are organised, and the kids love these sessions, pleading with the volunteers to come back again for another ‘fun day’.

Inspiring and inspired

NBD is not just helping underprivileged kids realise their potential, the movement is also having a profound impact on its volunteers. Several graduate students, particularly in top institutes like IISc, suffer from ‘imposter syndrome’, a psychological pattern in which an individual doubts their skills, talents, or accomplishments. Rinkumoni Chaliha, another longtime volunteer and a PhD student at the Department of Inorganic and Physical Chemistry, explains, “Campus life isn’t easy. Many students, including me, go through a difficult time navigating the rigorous research environment. Sometimes you’re bogged down by dissatisfaction and worthlessness, and I feel being part of NBD helps. Those kids are looking forward to meeting us on the weekends, and we feel rejuvenated, bringing joy to their faces and helping them envision a future, and throughout this process, we start to feel worthy.” She adds, “The large group of volunteers become your new friends, and you end up making meaningful connections for life. And I think that is the secret behind how this movement has sustained for over 19 years now.”

NBD is not just helping underprivileged kids realise their potential, themovement is also having a profound impact on its volunteers

Some volunteers credit NBD for reigniting their passion for teaching. After a postdoctoral stint at NCBS, Pankaj decided to co-found an educational start-up, Seed2Sapling Education. The company focuses on helping students and teachers in building a vibrant learning atmosphere in classrooms. He and five other co-founders are alumni of IISc and were inspired by their time as volunteers at NoteBook Drive. Another unique aspect of NBD is that there is no central governing body. The group is composed only of volunteers, who are an ever-growing and ever-changing set of people – in that sense it is truly an organic initiative. It has fostered a culture of inclusivity, encouraging diverse ideas and people to take responsibility equally.

The past couple of years, with the ongoing pandemic, have been difficult for NBD and the school children. But they are slowly getting back to normal. NBD volunteers have restarted their activities and are trying to introduce the initiative to newcomers on the campus in order to attract more volunteers and funds. They are excited for the next year as it marks twenty years of their sustained movement. As Pankaj reflects on the past two decades, he adds, “We won’t be able to bring a sea of change, but we can make a big difference in a small cohort of aspiring children, and more importantly the volunteers, who get a new perspective of looking at the education system and society at large.”

Gouri Patil is an Integrated PhD student at the Department of Physics and a former science writing intern at the Office of Communications, IISc