11 December 2019 marks the 137th birth anniversary of Max Born, who came to IISc on CV Raman’s invitation

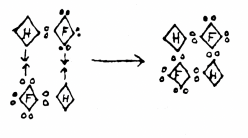

The Mysterious Number 137 was the title of a lecture that Max Born delivered to the South Indian Science Association in Bangalore on 7 November 1935. Called the fine structure constant α, 137 is a dimensionless entity (its value is actually its reciprocal), calculated using the charge of an electron, Planck’s constant and the speed of light. Since the early 1900s, some physicists have suggested that this number could be at the heart of a Grand Unified Theory because it combines electromagnetism, gravity and quantum mechanics.

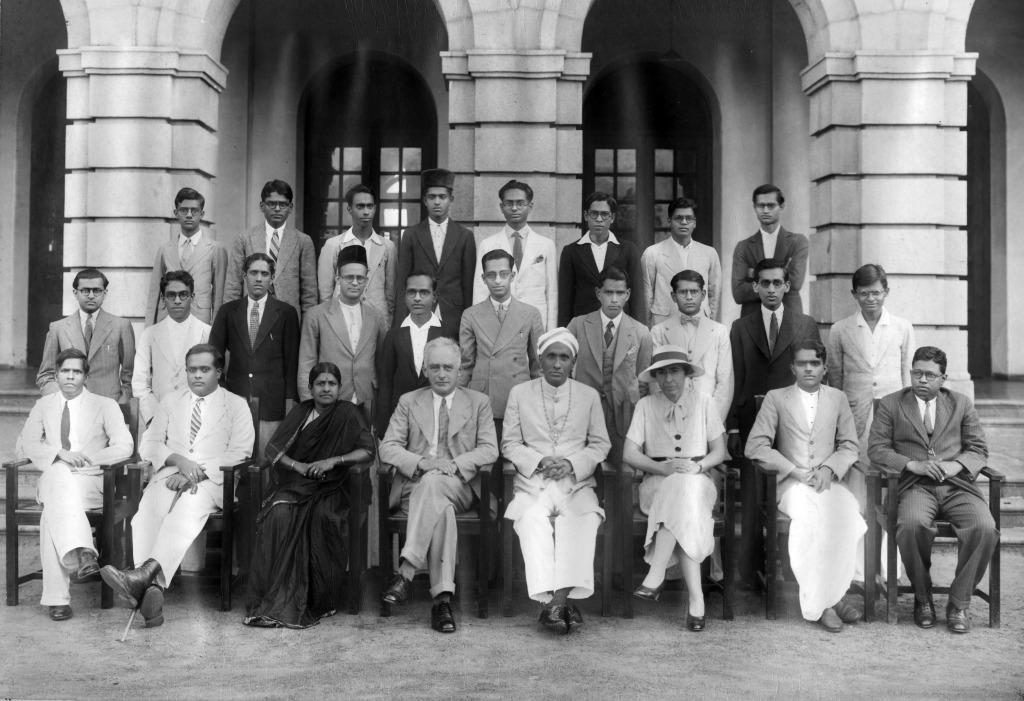

The talk was among over 30 lectures that Born gave, both within and outside the Institute, in his capacity as a Reader in Theoretical Physics at IISc, a position he held for six months. The Institute’s 1935-36 Annual Report states that his presence provided great stimulus to the work in the Physics Department, which had just been established by IISc’s Director CV Raman. The report adds that besides giving lucid lectures, Born continued his own investigations and directed theoretical physics research in the department. But during this period, a political drama, in which Born inadvertently became an actor, was also being played out – one that determined not just his future at IISc but also that of Raman and the direction of research at India’s best known science institution.

§

When Born arrived in IISc on 28 September 1935, with his wife Hedwig (Hedi), he was already a distinguished physicist who was closing in on his 53rd birthday. In the 1920s, along with the likes of Erwin Schrödinger, James Franck, and Werner Heisenberg, he had been instrumental in developing the foundations of quantum mechanics, the theory that describes nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. As a professor at the University of Göttingen, he mentored several physicists, including Enrico Fermi, Robert Oppenheimer and Pascual Jordan – besides his assistant Heisenberg – making the German university one of the most important centres for physics in the world.

But not long after, Born’s life – both professional and personal – came to a crossroads. In 1928, he had been nominated by Albert Einstein for the Nobel Prize in Physics (Einstein himself had a strained relationship with quantum mechanics. Annoyed with its probabilistic nature, he famously declared in a letter to Born that “God does not play dice with the universe”). The Nobel Prize Committee, however, did not deem Born’s work worthy of the honour, even though Heisenberg received the Prize in 1932 and Schrödinger the following year (Born eventually won the Prize in 1954). But, by the early 1930s, being overlooked for the award was not what was uppermost on his mind.

Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933. “Then one evil event followed the other,” writes Born in his autobiography My Life: Recollections of a Nobel Laureate. On 25 April, he was suspended from his job because of his Jewish heritage. In the coming months, he was also to lose his doctorate, professorship, property, and citizenship. When he was suspended, Born’s first thought was about the effect it would have on the research at Göttingen. “All I had built up in Göttingen, during twelve years’ hard work, was shattered. It seemed to me like the end of the world,” he writes. His next thought was the safety of his family. “I went for a walk in the woods, brooding on how to save my family,” he adds. He realised that they – Max, Hedi, and their daughters Irene and Gritli – had to leave their homeland. In early May, they fled Germany by train and made their way to northern Italy.

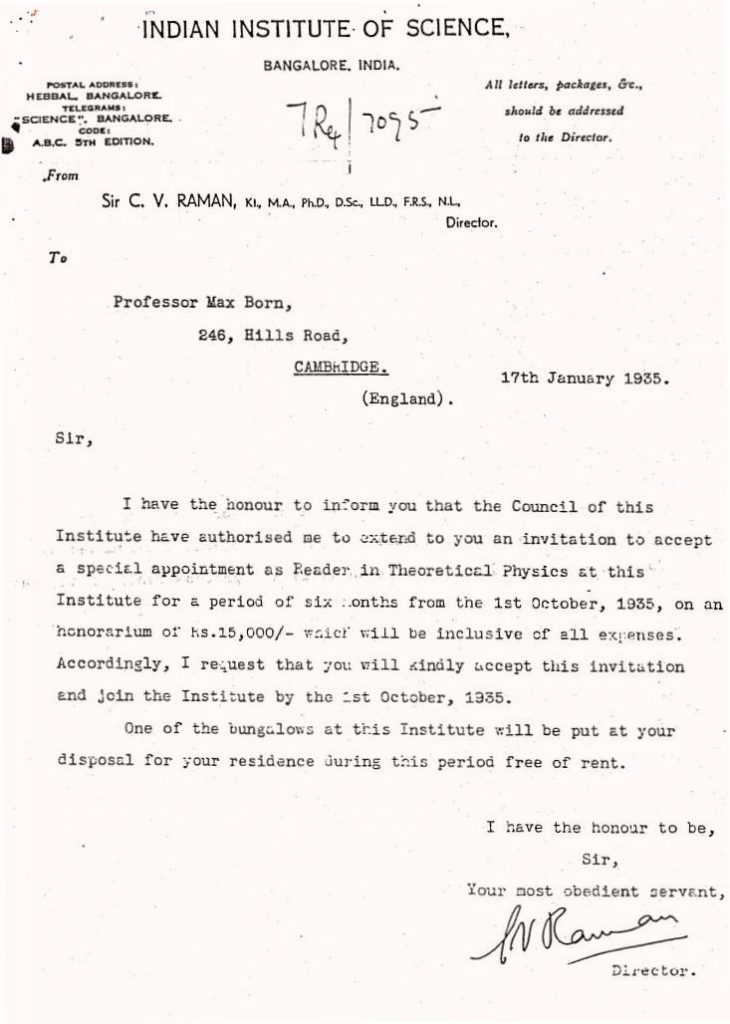

The family then moved to Cambridge, UK, where Born had been offered a temporary lecturership position. During his time there, he received a letter from India. It was from Raman. The Indian physicist had, with the help of KS Krishnan, discovered what came to be known as the Raman Effect. The discovery, for which Raman was knighted in 1929 and won the Nobel Prize in 1930, provided further evidence for the quantum nature of light.

During his time there, he received a letter from India. It was from Raman

In the letter, Raman asked Born if he could recommend names of “young and efficient” theoretical physicists who might be interested in working in IISc. The latter responded by saying that even if he did, he could not persuade any of them to go to Bangalore without knowing much about the place. Then Raman wrote back asking Born if he himself could come to IISc for six months to “have a look at the place.” Born was inclined to make the move since his Cambridge appointment was going to end soon. He consulted with Hedi, who readily agreed to join him. At Cambridge, she had no friends, felt cut off from her roots, and was overworked, according to Born. Once Born said yes, it did not take Raman long to convince the Governing Council of IISc to create a temporary position of Reader in Theoretical Physics. For his services, Born would receive an honorarium of Rs 15,000 for a period of six months, more than what he was getting paid at Cambridge.

§

The Borns arranged for their children to be sent to live with families of friends and set off for India on the steamer Staffordshire. They arrived in Cochin (now Kochi), where they spent a day, and travelled to Bangalore from there. At IISc, they were received by Raman’s wife Lokasundari Ammal, who took them to a two-storey bungalow, which was to be their home for the next few months. “We had a large garden with beautiful trees and flowers,” writes Born, “and two tennis courts which were screened off by marvellous bougainvillea shrubs. The Raman family lived in a similar house just across the road.”

The Borns did not get to meet Raman for the first few days. And when they did, they were fascinated by his appearance and talk. To Hedi, Raman in his Indian dress and turban looked like a prince from the Arabian Nights.

During their stay, the Borns played tennis and socialised, mostly with Indians. They also travelled to Bombay, Agra, Nilgiris, and Mysore for the annual Dasara festivities. Hedi, in particular, seemed to be enjoying herself in India, in stark contrast to her time in Cambridge. This in spite of two major illnesses, including a nasty sunstroke which kept her in bed in a dark room for weeks together.

Born had mixed feelings about India. Though the stay was pleasant, he was disconcerted by certain aspects of life here: the poverty, the gulf that divided Indians and the British, the opulence of the Maharajas, and the caste system.

In Bangalore, Born also got to meet Mysore’s Dewan Mirza Ismail, whom he came to admire. “He was a Mohemmedan while the majority of the inhabitants of Mysore were Hindu. But this seemed to cause no friction,” he writes. When Ismail asked Born whether he knew any good architects to work for Mysore State, Born suggested the name of his nephew Otto Koenigsberger, who had also fled Germany. Koenigsberger eventually became the State Architect of Mysore, designing and building several prominent buildings in Bangalore, including in IISc.

On the academic front, Born spent a considerable amount of his time preparing for and giving lectures. Even though he and Raman often had “violent” discussions on modern theoretical physics, they got along well. Raman was keen to create a permanent chair for the German in the Institute. When he asked Born about whether he would be willing to stay on in Bangalore, Born – and Hedi – were open to the idea. Two search committees were set up, one in Bangalore (led by Raman), and the other in London (led by the physicist Ernest Rutherford). This seemed a mere formality – both committees were in favour of offering the position to Born.

However, Raman also had to seek the approval of the Senate – the faculty body – and the Council. With some persuasion and questionable tactics, he was able to convince them to create a Professorship in Mathematical Physics at IISc (Born writes that Raman later informed him that he intentionally sent invites to his “enemies” on the Council late so that they would not show up).

I was so shaken that when I returned to Hedi, I simply cried,” Born writes

It was during the Senate meeting that Born first got a whiff of the ugly spat between Raman and IISc’s establishment. At the meeting, Kenneth Aston, an Englishman recently hired as a professor in the Electrical Technology Department, attacked not just Raman but also Born. “The English Professor Aston went up and spoke in a most unpleasant way against Raman’s motion, declaring that a second-rank foreigner driven out from his own country was not good enough for them. This was particularly disappointing since we had been kind to the Astons, as I mentioned before [they stayed as guests with the Borns when they arrived until their bungalow was ready]. I was so shaken that when I returned to Hedi, I simply cried,” Born writes.

§

In 1933, when Raman became Director of IISc 24 years after it was founded, it still had only four departments: General Chemistry, Organic Chemistry, Biochemistry and Electrical Technology. And research was skewed heavily towards industrial applications. Among his main tasks as Director was to establish a physics department, a recommendation that had been made by two government-appointed review committees, the Pope Committee in 1921 and the Sewell Committee in 1931.

Once the department was set up, Raman – its only faculty member – initiated investigations in key areas of theoretical and experimental physics with his students, leading to several publications of high quality in a short period of time. But Raman realised that in order for him to make Bangalore a world-class centre for physics, it would need world-class physicists. He was particularly keen that IISc become a hub for atomic physics.

Raman’s tenure as Director coincided with the rise of the Nazis in Germany. Several physicists of Jewish heritage were being forced out of their country. Raman believed that he might be able to convince some of them to come to IISc. “[After setting up new lines of research], he then identified gaps in knowledge in India and adopted a strategy of trying to recruit to the Institute faculty from among the reputed scientists who were fleeing from the tyranny of Hitler,” says S Ramaseshan, Raman’s nephew and former Director of IISc, in a profile of his uncle in Current Science.

It was then that Raman invited Born to IISc. Later he also wrote to a few other Jewish scientists, including Schrödinger, who, according to Ramaseshan, wrote back saying that Raman’s offer arrived a bit too late as he had just accepted an offer from the School for Theoretical Physics in Dublin, Ireland. He adds that Schrödinger also expressed his regret that he could not settle in the land of the Upanishads.

Raman’s effort to bring international scientists to IISc was part of an ambitious project to make IISc be counted among the best in Asia, if not the world. “In walks a spirited giant who finds this set-up all wrong. His mind is full of visions of Cambridge and Caltech, and he wants to recreate their atmosphere in his backyard,” writes G Venkataraman, a condensed matter physicist and science historian, in his book Journey into Light: Life and Science of CV Raman. But it did not take long for Raman’s grand plans to be thwarted.

§

Opposition to Raman began with his attempt to speed things up at the “sleepy place where little work was done by a number of well-paid people,” as Born describes IISc. Raman’s enthusiasm to change the work culture at IISc was perceived as criticism of the establishment. But there were other reasons for the growing animosity between him and some faculty members as well as the Council.

Raman wanted the work in physical chemistry (he called it chemical physics), then being undertaken in the General Chemistry Department, to be conducted under his watchful eyes in the new Physics Department. The move upset HE Watson, a professor in the General Chemistry Department, who resigned in protest. Born suspected that there was more to this resignation than his resentment of an administrative decision. “Watson’s friends and he himself may have expected that he was to be the new Director after Sir Martin [Forster] retired. Certainly Watson did not like to continue under an Indian Director. I was told this by some of Watson’s English friends,” recounts Born in a letter to Rutherford written after he left Bangalore and returned to the UK.

In the early 1930s, IISc’s finances were not in great shape – the Mysore State had reduced its annual contribution from Rs 50,000 to Rs 30,000. But Raman, given his ambitious goals for the Physics Department, wanted more money, more than the capital grant of Rs 1 lakh (and the recurring sum of Rs 25,000) allocated by the Institute. “He therefore re-apportioned the budget to aid the fledgling Physics Department, an act which invited charges of embezzlement!” Venkataraman writes.

The situation was precipitated by Raman’s apparent lack of administrative tact – a flaw in his character that even his most ardent cheerleaders find hard to defend. “Raman’s ebullience and sharp tongue, his pride and prejudice, not infrequently surfaced to such levels that open mindedness and the future of the Institute had to take a backseat,” Subbarayappa concedes in his book In Pursuit of Excellence: A History of the Indian Institute of Science. “Raman went in there like a bull in a china shop,” writes Ramaseshan.

It was under these circumstances that Raman was working towards creating a permanent professorship for Born, a move that was not popular among some faculty members. The Born episode brought things to a boil, notes Venkataraman, leading to games of one-upmanship between Raman and the Council.

In the letter to Rutherford, Born writes that he did not see the unprecedented verbal attack on Raman and him at the Senate meeting as an isolated incident. He was convinced that the Council appointed Kenneth Aston as a professor to stir trouble and weaken Raman.

Amidst rising tensions, the Government in January 1936 appointed another review committee, headed by James Irvine, Principal and Vice Chancellor of the University of St Andrews, UK. Its mandate was to look into the working of the Institute and to make recommendations on how it could fulfil the purpose for which it was set up, while taking into account its financial resources.

Some historians have suggested that the real reason the committee was instituted was to clip Raman’s wings and undo his controversial decisions. Born concurred. He writes that Raman’s enemies in the Council had made up their mind to get rid of him. “It was evident to me from the beginning that they had received instructions beforehand.”

The Irvine Report was submitted in late March that year. Among its many suggestions included the appointment of a Registrar, thus creating a parallel power structure in IISc. It also blamed Raman for the faulty use of Institute funds. While appreciating the work done in physics, the report expressed concern that the “centre of gravity” had shifted from chemistry to pure physics. It believed that modern mathematical physics “has little contact with industry, and in this respect cannot compete with Chemistry as a subject likely to be of service to India.”

On the issue of Max Born, the report said that though “the presence of an eminent mathematician such as Dr Born would have a stimulating effect on the activities of the Department of Physics,” the recently-approved position of Professor of Mathematical Physics should be abolished. The Committee justified the suggestion on the basis of the prevailing fiscal condition of the Institute.

The recommendations of the report were discussed at length at an extraordinary meeting of the Council in June 1936. At the meeting, a memorandum was also circulated by Raman critiquing many of its suggestions. But a majority of the members present were in favour of accepting them.

“Meanwhile, the opposition to Raman had been gathering momentum,” Subbrayappa writes. He was becoming increasingly isolated. Born, who left India at the end of his six-month appointment, pleaded with Rutherford to intervene and “save Raman from a precipitous fall,” Subbarayappa adds. However, Rutherford’s attempted intervention had little impact on the Council. Eventually on 19 July the following year, Raman was forced to resign as Director but continued as a professor and the Head of the Physics Department until he retired in 1948.

§

Born and Raman remained friends for a few years after the former left IISc. Raman even invited Born to become an Honorary Fellow of the Indian Academy of Sciences, which he founded. But their relationship soured in later years, thanks to an intellectual dispute that had its origins in Born’s lectures in Bangalore. In IISc, Born devoted a few of his talks to the theory of lattice dynamics – the theory of how atoms in crystalline solids stick to each other and vibrate. But Raman felt that the theory did not explain the experimental observations he had made in his lab.

But their relationship soured in later years, thanks to an intellectual dispute that had its origins in Born’s lectures in Bangalore

During the ensuing debate, which went on for many years, most theoretical physicists threw their weight behind Born, who had become the Tait Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh in the UK. In 1947, Born’s student Helen Smith’s experiments also supported his ideas (though research in the 1950s and early 1960s showed that Raman was partly right). Raman seemed to take it personally.

The Borns met the Ramans twice after they left India. The first was at Bordeaux in France for the 25th anniversary of the discovery of the Raman Effect. At the reception, they greeted each other cordially, according to Born. But for the rest of the congress, Raman “was nervous, excitable and aggressive.” The second time they met was at one of the Lindau meetings of Nobel Laureates in Germany. Again, Raman greeted them cordially, but the next day his attitude changed, writes Born. “He must have suddenly remembered that I was his ‘enemy’.”

Born and Hedi were especially disappointed that the controversy affected their relationship with Lokasundari. “Hedi and I regret all this and particularly the split between us and Lady Raman, whom we loved dearly,” he laments.

Nonetheless, Born was an admirer of Raman’s devotion to research and the risks he was willing to take for Indian science. “It makes me sad to think that by inviting me to India and trying to keep me there permanently he has brought himself into a precarious situation, and had to give up this leading position at the [Indian] Institute of Science.”