A short history of the messes

In 1954, Morris Travers, who had been IISc’s first Director, wrote to AG Pai, the then-Registrar. In a letter looking back on his time at IISc, Travers (who had worked at theInstitute from 1906 to 1914, and had been involved in setting it up) said:

“When I first went to India one of the first things I did was to look into the question of housing and feeding students drawn from all over India. I came to the conclusion that I should have to have several messes. Then I was right, for when we opened I found that we had to have five. Then a Muslim student turned up, and as no mess would take him in, I had to make a oneman mess for him. I still wonder how fish-eating Bengalis get on with meat-eating Punjabis.”

If it should sound strange that five messes were necessary, here’s something that will make it sound stranger: classes began in 1911, and that academic year saw only about 20-odd students at IISc. A 1911 leaflet printed just before IISc opened to students said of the hostel, “There are seventy-two single rooms, and eight mess rooms, each with its own store and kitchen, so that members of different races and castes can form separate groups, each observing its own customs.” Later documents say provisions were originally made for 10 messes.

The men’s hostel was originally built to accommodate 72 students, with 10 different messes for people of various communities

When IISc first opened to students, the world was a rather different place. India was still governed by the British and by regional kingdoms, and journeying abroad involved arduous journeys by sea. Bangalore had only recently become one of the first cities in Asia to get electric streetlights. Travel was limited, and so was people’s exposure to other Indians. The influence of caste and community on one’s identity was strong. With food being a large part of cultural practices – including the dictates of caste ‘purity’ and ‘pollution’ – this influence was strong enough that caste and community were taken into account in the very structuring of the hostel and its messes.

In the early years, every student at IISc who lived in the hostel had his own room and ate in the mess of his choice (the students’ hostel only accommodated men). But in the 1940s, a combination of factors meant that things would soon have to change. India’s freedom struggle was building, and more women were knocking on the doors of IISc (in 1942, a small hostel was built for them that would quickly prove insufficient). A period of expansion had begun at the Institute, kick-started by World War II, with new engineering departments like Aeronautical Engineering being set up. That meant an inflow of more students, and there was talk of having to “double seat” all the rooms in the men’s hostel. Nine messes were in operation in the early 1940s, but they occupied too much space – space that could be used to accommodate even more students at the hostel.

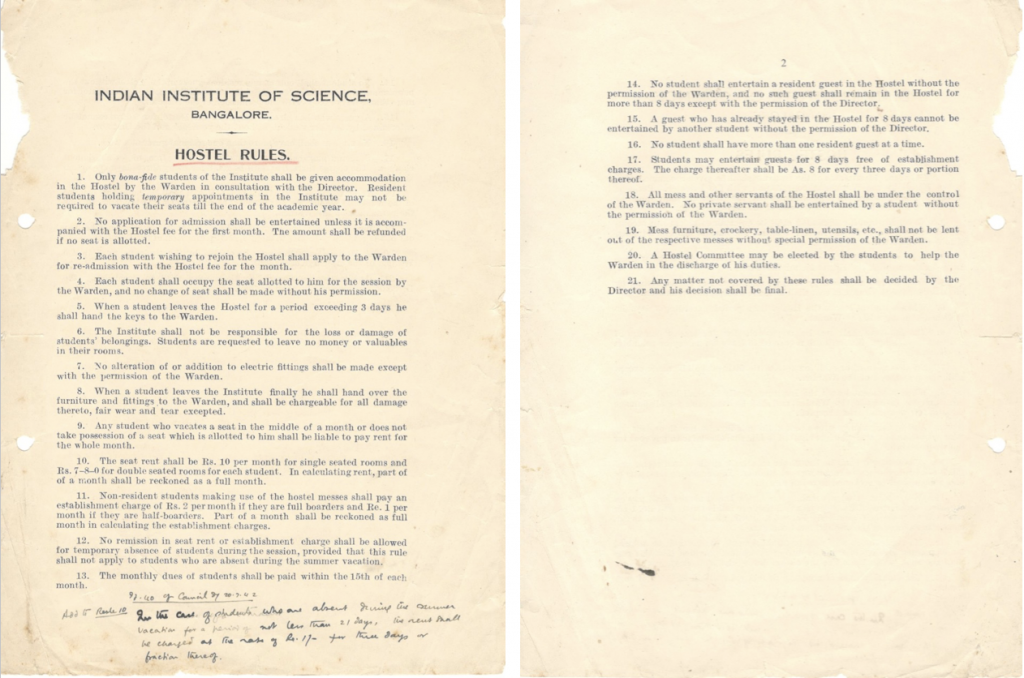

With over 200 students on campus in total, new and unpopular rules for the hostel and messes were formulated and circulated in 1942, including this one that seems strange for several reasons today, in the 21st century: “All mess and other servants of the Hostel shall be under the control of the Warden. No private servant shall be entertained by a student without the permission of the Warden.” It was also decided that a new “Common Dining Hall” would be built and the nine existing individual messes shut down. Once the plan became known, it set off a widespread student protest in 1943.

In a 1943 letter to the Director, a student who claimed to be on indefinite hunger strike complained about the “curtailment of their liberties” in having a common mess

According to Violet Bajaj, a 101-year-old alumnus who studied at IISc in the 1940s, the Institute was a “caste-ridden” place at the time, and that even Iyers and Iyengars, two Tamil Brahmin communities, would not eat with each other (there were no such divisions among the women students, she points out – they ate together in their own hostel). The idea of a common mess – which was promoted as way of bringing unity among students – seemed the last straw, setting off tensions that already appeared to have been brewing between students and the management over the new hostel rules.

In a 1943 letter to Director JC Ghosh, a student who claimed to be on indefinite hunger strike named M Jagannadha Rao complained about the “curtailment of their liberties”. “I know that all other students have also unanimously opposed the idea and did all that is constitutionally possible – by way of individual letters, combined representations and collective demonstrations – to prevent a Common Mess coming into existence,” he wrote, asking for “democratic principles rather than using these imperialistic methods against which a greater war is taking place.”

Rao’s letter makes it sound like the conflict was less a case of liberal versus conservative ideas than the management’s financial considerations versus students who demanded a say in decisions affecting them. Minutes of Council meetings from 1942 do show that GT Kale, who served as Librarian, Lecturer in French, and also took on Warden and Registrar duties at various points during his time at IISc, was involved in preparing a note on the “probable saving” in having only two messes – a vegetarian and non-vegetarian one. But it was the Director’s personal beliefs that appear to have been the original driving force for the Common Dining Hall. In an interview with the Archives and Publications Cell in 2008, Ghosh’s children mentioned that he disliked the practice of having people from different provinces eat at separate messes, and felt that “for the integration of the country”, eating together was important. In an introduction to a collection of Ghosh’s papers published by the Asiatic Society, Sushil Kumar Mukherjee writes that at IISc, Ghosh “did not like caste and creed way of students’ hostel [sic]” and was insistent that the students eat side by side. Mukherjee mentions that when Ghosh became Founder-Director of IIT Kharagpur in 1950, he persuaded students to eat together there as well.

But back in 1943, the protests appear to have gotten out of hand, prompting a statement to IISc’s Council by Sir Sorab Saklatwala on behalf of the representatives of the Tata family, in which they indicated they were unhappy with how the issue was being managed and felt strongly that there was no “proper disciplined atmosphere”. Included in their statement was a threat: “[A]ttempts are made from time to time by some members of the staff as well as the students to obstruct well-considered policy of the Council. If such an atmosphere is allowed to continue it will be very difficult for the Tatas to continue their policy of helping the Institute by means of ad hoc grants for research and expansion projects, and for the institution and maintenance of scholarships.”

The Council went ahead with the plan of the Common Dining Hall, which came up in 1944. The kitchens for vegetarian and non-vegetarian food were built on opposite sides of the building. But the tradition of students being in charge of deciding the menu and its rotation at the mess continued – as it does even today.

With every significant expansion at IISc, the mess system has expanded too. In 1949, the mess split into A, which served South Indian vegetarian food, and B, which served vegetarian and non-vegetarian North Indian food. Around the late 1940s or early 1950s, women began to eat at the messes too. In the 1970s, a C mess was added as well – a “universal mess”. All of these have gone through various iterations and shifted location a few times – some even appear to have loosely acquired their own regional identities. The latest addition to IISc’s messes is the D mess, set up in 2012.

For many IISc alumni through the years, the messes have held a powerful place in their memory. In their accounts of life at IISc in Down the Memory Lane and Reminiscences (two collections of memories put together for IISc’s centenary celebrations by the Archives and Publications Cell and the Office of Development and Alumni Affairs), former students and faculty spoke fondly of their messes, as did members of the alumni association who recently wrote to Connect when asked about the messes.

Many recall the quality of food, and specific dishes such as the “Emergency Curry” – made of tomato, onion and potato as a quick fix if students arrived after food had run out – and the unlimited quantities available. BC Pradhan, who was a BE student in Metallurgy from 1958-60, writes in high praise of the mess, saying, “[W]hen I was a student, food in the mess was excellent and is the best I have tasted at any time in my life, including that in the 5-star hotels and many countries I have visited in the last 50 years.” Several alumni mention the dosas served on Sundays at the A mess, which once drew visitors from the city to campus. Renuka Ravindran, who completed a PhD in Mathematics in 1968 and went on to be Professor at the department as well as a Dean at IISc, speaks of the Wednesday night special at the B non-veg mess: “Wednesday nights were special with dosa and half a grilled chicken – with the champion consuming up to 20 dosas. […] There were special dinner days – where we ate a fare, which was truly royal, under the full moon outside.”

Alumni also spoke of the role the messes played in their social lives. Some write about themselves or fellow students being gauche when it came to table manners, and learning to use forks and knives for the first time. Being in close contact with others at the mess also meant witnessing some peculiar food habits. N Siva Kumar, a BE student from 1983 to 1986 who was Mess President for two years, writes, “The batch was made up of students from a cross-section of India and it indeed looked like a mini-India with a southern bias. We enjoyed the mess and remember us calling the ‘A’ mess as ‘Madras Café’ and ‘Aiyar Mess’ as they served only vegetarian [food] and I remember ‘A’ mess using separate plates for serving omelettes as the vegetarians refused to eat from the same plate!” VC Amanan, who supervised messes at IISc from 1980 to 2017, laughs as he recalls seeing students stirring jam into their coffee before drinking it up.

“I remember ‘A’ mess using separate plates for serving omelettes as the vegetarians refused to eat from the same plate!”

Others mention that at IISc’s messes, they were learning to mix with people of different genders for the very first time in a casual environment. N Appaji Rao, Emeritus Professor at the Department of Biochemistry, recalls his time as a student between 1956 and 1960. He writes, “The mess served good food and was lorded over by a strict supervisor who kept watch on your attendance (much stricter than the departments) and chased away any student who dared to sit at the central table. It was reserved for the ladies! It was all right to meet them in the sylvan surroundings of the campus but not share a lunch in the mess!”

One common feeling expressed by several alumni was the genuine warmth they shared with mess staff – many used the word “family” to describe the relationship between students and mess staff. PR Mohapatra, a student and later faculty member at the Department of Aeronautical Engineering from the 1960s onwards, says, “The servers were seen more like brothers by the student community rather than as employees.” Over 60 years since they graduated, some still remember the names of bearers, cooks and supervisors at the messes.

Although agitations over the mess never quite reached the same heights that they did in 1943, things haven’t always been smooth sailing. There were student agitations in 1956, according to an alumnus who joined IISc that year, when the mess rate rose beyond Re 1 a day. A series of letters in the Archives shows that the Student Mess Committee locked horns with the management in 1956 because there was insufficient crockery for the mess to run smoothly. The messes used porcelain cups and plates made of porcelain – a cheaper option at the time than stainless steel – which were not replaced as often as they were broken.

“One incident that my friends and I will never forget,” writes Gopi Chandran, who was a student at the Department of Inorganic and Physical Chemistry from 1984 to 1991, “is the time when mess staff went on strike for a few days due to tighter controls from students in the mess community. During this time with no food in the mess the institute tried outside vendor support. This did not work that well. We as students decided to cook for 400-plus students. There was a big tea put in place and I was one of the cooks. This was the best time I have seen in my life. Enemies turning friends, everybody chipping in with whatever skills they had in cooking. We were able to deliver food a few notches above the normally good quality from the staff. We celebrated after the strike was called off and could see the staff feeling bad about what they did and they quickly made up for their only mistake. Family became one again in no time.” G Padmanaban, a former student (with fond memories of the “Emergency Curry”) at the Department of Biochemistry who went on to be professor and later Director of IISc, writes, “I was appointed as Deputy Director [in] 1993.[…] There were always ticklish issues with sections of employees and between students and mess employees. We were even gheraoed once for not taking immediate action on a complaint!”

From the mid-1980s onwards, as the number of students grew and the business of managing the messes was handed over to contractors rather than permanent employees, that feeling of being around family appear to have slowly eroded. Today, not all recent graduates remember the messes fondly. “One place that signifies an excess of security and discipline is our hostel mess. Students are required to adhere to timings, always carry ID cards to have meals or be at the mercy of the mess card checker,” writes Arjun Gopal, who completed an ME from the department of Chemical Engineering in 2017.

It isn’t only students who have been fed on campus – employees once had a mess of their own, and today, faculty are still served food at the Faculty Club. Currently, Prakruthi, Nisarga, Nesara, and most recently, Tattvah (opened in 2018) are among the restaurants and cafeterias that offer everyone on campus – whether students, staff or faculty – a range of options to choose from as part of a long tradition that also includes tea, coffee and juice joints. Students from as far back as the 1970s recall being able to get food on campus late at night after leaving their laboratories. Eateries existed at the time too: the predecessors of Nesara and the like. Prahlad Harsha, from the Civil Engineering class of 1977, says that when he and his friends ran out of money at the end of the month, they would hang out at the cafeteria on campus. He says, “Our order to the waiter would be, ‘pani, bina ungli’”!

For more stories about the mess and accounts by alumni, follow the links below:

A History of the Messes: Dining at IISc

Eating Together: A Student’s Letter of Protest

The Common Dining Hall: ‘Neither Indian Nor European, But Something New’

The 1940s: Strange Encounters of the Kheema Kind

The 2000s: How to Get Dosas Without Waiting in Line

Interview with a Mess Supervisor: ‘They Still Remember Our Food’