Eric Lord, a British-born mathematician, was a visiting scientist at IISc for over two decades. He first came to the Institute in 1972, and later returned to Bangalore, the city he loved, for good. A man of varied interests, Eric has written books about general relativity, mathematics, crystallography, and paranormal phenomena. He has also illustrated children’s books. He spoke to Connect about his association with IISc and his work. Excerpts from the interview.

How did you arrive in India?

I got my PhD from King’s College London in 1967. I had published two papers at the time. And out of the blue, I got a handwritten letter from India, from Madras [now Chennai], from somebody I had never heard of. It was from Alladi Ramakrishnan of Matscience [The Institute of Mathematical Sciences]. He said, “I’ve just read your paper; we’ve been doing similar work here,” and sent me a reprint of one of his papers. I thought “that’s nice, somebody is appreciating what you’ve done” and then forgot all about the letter until years later when I got it out again and wrote to him, saying, “Can I come and work with you people?” Alladi’s reply was: “Yes. We can offer you a year as a Visiting Scientist. We can’t offer you much money because India is a poor country but Madras has a beautiful beach.” I spent a year in Matscience; that was 1971.

So this was in the early years of Matscience.

Yes, it was very small back then. It was on the Adyar Polytechnic Campus and had about 30 people altogether, students plus staff.

The year went by quickly, I wanted to stay in India longer. I talked to Alladi about the possibility of extending my appointment, but he was reluctant to do that. So I wrote to various Indian research institutes, including the Ooty observatory, places like that. The first enthusiastic reply I got, from about a dozen letters, was from KP Sinha of the Indian Institute of Science.

I didn’t know much about Sinha. He was in the departments of Physics and Applied Mathematics, a professor in both, and he had this bunch of half a dozen students. He was so kind and nice and pleasant to me but also very quiet and shy – like me. As soon as I met Sinha he asked me to give a series of lectures on Einstein’s relativity. They were very well attended, to begin with; the lecture hall in the Applied Mathematics department was full. It dwindled later because attendance was ‘optional’, but Sinha came to every one of those lectures. Although he was not a relativist – his field of expertise was solid state physics – he picked up enough knowledge from my lectures to take on students in relativity! I started working with him and his students and stayed there for about three or four years.

It was a nice time of my life. I was a Research Fellow, a foreign ‘Visiting Scientist’, so I never had any tedious responsibilities – no ‘core’ courses, no exams to set, no committee meetings. I was free to just get on with my research and interact informally with the students. It was a happy time.

I left in 1975 to go to West Germany on a Humboldt Fellowship and after that, I was in Edinburgh for six years. There was a gap of nine years before I came back to IISc.

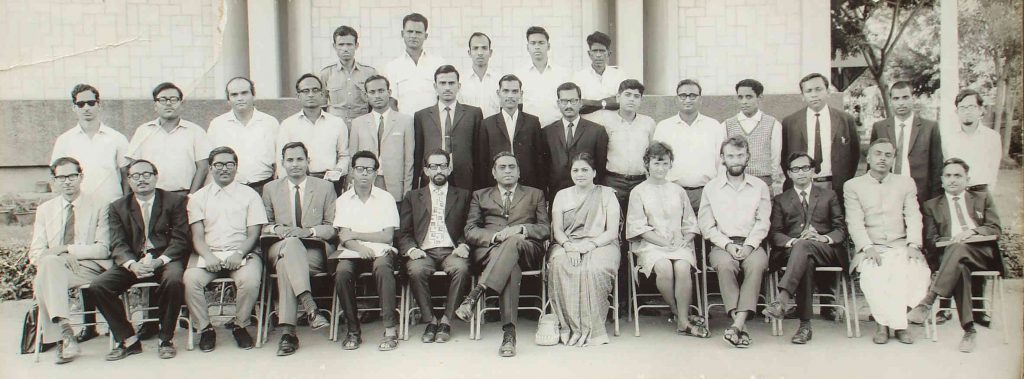

Alladi Ramakrishnan is seated in the centre, and Eric Lord is fourth from

right. (Photo courtesy: Eric Lord)

What prompted you to come back?

I always had a feeling that Bangalore is the place I wanted to be. We had Indian friends who lived in Holland (The Netherlands) people we had met in IISc that first time – Krishna and Dhun Prasad. We visited Holland a couple of times to be with them, and they visited us in Edinburgh. I remember Dhun asking me, “If you could live anywhere in the world you’d like, where would you choose?” I said I’d be in Bangalore!

It’s hard to believe how lovely Bangalore was in the 1970s. It’s got no resemblance to this busy, noisy metropolis it’s become. But one gets used to change and it’s my home now.

“It’s hard to believe how lovely Bangalore was in the 1970s. It’s got no resemblance to this busy, noisy metropolis it’s become. But one gets used to change and it’s my home now”

In 1983 I wrote to Sinha again and said, “I hope you remember me. I’d like to come back and work with you again.” Being Sinha, he said, “Yes, please come. I can provide you with a Senior Research Fellowship.” So in 1984, I came back. He just kept renewing that fellowship for three or four years, and then there was a shortage of funds. For about a year or more after that I had no position, but of course I kept on working; I became interested in ‘optimisation algorithms’ and collaborated with SK Sen and his student Venkaiah.

You had a position in the Department of Metallurgy (now Materials Engineering) and worked with Srinivasa Ranganathan there. How did that come about?

I first met Srinivasa Ranganathan of Metallurgy in 1991, as a consequence of my article “Quasicrystals and Penrose Patterns” in Current Science.

I’m not superstitious but sometimes in life, it’s as though things have been arranged for you and coincidences keep happening that push you in a certain direction. I used to be on the campus, just walking or cycling around. I would bump into Rangu [Ranganathan] “just by chance” every few days. He would go around the campus on a motorbike. He knew about my situation – that I had work but no official paid position. One day, he said: “Alan Mackay [British crystallographer at Birkbeck College, University of London] is coming and he has some software for investigating minimal surfaces and, in particular, those with ‘triple periodicity’ like crystals. Would you like to work with Alan and me on this topic?” I said, “If you can get me a position in your department then, yes, of course I will!”

I went to the library and studied crystallography, learned about the space-group symmetries and things like that, and read up on minimal surfaces. I used to keep bumping into Rangu every few days and showing him some little sketches about my ideas. Eventually, Alan came and introduced me to the software. I didn’t know anything about computers then! Alan loves Bangalore and came very frequently over the next few years. I learned from him how to use computer graphics and we thoroughly enjoyed working together.

You wrote a book with Ranganathan as a co-author.

Yes, the work we did together eventually led to our book “New Geometries for New Materials” (Cambridge University Press 2006).

“I had no official responsibilities at all – just do something interesting and publish it to justify my existence”

What was your work in the Metallurgy department like?

It was all very informal. There were regular Saturday talks in the department and occasionally when my time came I would give a talk on some aspect of crystallography. I had no official responsibilities at all – just do something interesting and publish it to justify my existence. Sinha first, and then Rangu later, kept funding me as a Visiting Scientist. I couldn’t be a faculty member because I wasn’t an Indian citizen – I am now. (I probably have set a record for the longest ‘visit’ to IISc!) But that was okay – my only responsibilities were to get on with my research work and help the students with theirs. Rangu’s students, of course, had practical work whereas I was totally theoretical. They’d be involved with preparing alloy samples, studying them under the electron microscope and obtaining diffraction patterns. The theory involved geometry, understanding how the molecules are arranged in crystals and quasicrystals – I could help with that.

The students were great fun. Being with them kept me youthful. We would go out into town together to have dinner and drinks. For me, it was like being a student again!