Violet Bajaj, a contemporary of Anna Mani and Rajeswari Chatterjee, talks about her years at the Institute and beyond

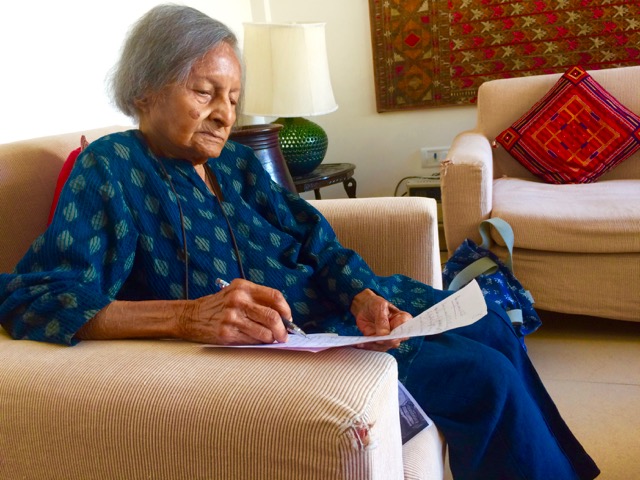

Violet Bajaj is 101 years old. She sits in her room before dinner, with the Gerald Seymour thriller she is currently reading on the table before her. Reading is her favourite hobby, and a low cupboard near her desk has a few books neatly arranged on it, ranging from novels by Agatha Christie to Naguib Mahfouz. Detective novels are her favourite things to read, she says, and it comes as no surprise that she should love a good whodunit. Asking questions, as it turns out, is something of a way of life for Bajaj, whose search for knowledge even as a young woman took her from Jhansi to Lucknow, Bangalore, Pune and Delhi. Around six years of her life were spent studying biochemistry at IISc, where in her twenties she lived through incredible times – World War II and India’s struggle for independence – and she was a part of one of the earliest generations of women in India to study at a modern science institution. Whether it was studying the RNA and DNA of a fungus and questioning societal conventions in her youth, or maintaining a keen interest in current affairs now, at over a century old, it is hard not to see Violet as someone with queries always at the tip of her tongue.

Today, Violet lives with her daughter Sheela Bajaj and son-in-law Sudhir Sahi, in Sheela’s flat in a quiet south Delhi neighbourhood. She was born on 21 January 1917, in a Goan family that lived in Agra. When Violet was three, her family moved to Jhansi, where she grew up.

Violet studied at St Francis Convent in Jhansi, where she finished her Senior Cambridge examination (the equivalent of matriculation). She says that no science subjects were taught at her all-girls’ school – she had only studied English, Geography, History and Maths. But she wanted to study medicine like her older sister Blanche, and since there was no college in Jhansi, she joined Isabella Thoburn College in Lucknow for a four-year BSc. For the first time, she was studying Physics, Chemistry, and Biology, which she found tough. After completing her BSc, she joined Lucknow University for an MSc in Chemistry. By then, her parents had moved to Bangalore, where some of their relatives were, and lived in a bungalow on Rest House Crescent. “One of my professors at Lucknow said, ‘If you’re going to Bangalore, why not apply to the Institute?’ So I did. [Until then] I had never heard of it. Initially I joined the Department of Chemistry to study Organic Chemistry, which I did not like. So I shifted to Fermentation Technology.”

“One of my professors at Lucknow said,‘If you’re going to Bangalore, why not apply to the Institute?’ So I did”

The Fermentation Technology Section, as it was known at the time, was set up in 1942 under the Department of Pure and Applied Chemistry. In 1951, it was transferred to the Department of Biochemistry, and in 1953, it became an independent entity as the Fermentation Technology Laboratory under M Sreenivasaya, who had been Violet’s teacher (as well as Kamala Sohonie’s). In 1988, it became part of the Department of Microbiology and Cell Biology.

“I loved the practical aspect of science very much,” Violet says, adding, “I loved the experimental side of chemistry. And biochemistry was a subject I really took to. It was a new science, just coming up.” What she found most fascinating about fermentation technology was its application of chemistry to living organisms. She studied Aspergillus niger, a fungus that causes black mould in some vegetables and fruits for her PhD thesis. She also co-authored four papers (in the Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics) between 1953 and 1957, while working towards a PhD under PS Krishnan at the National Chemical Laboratory, Pune.

For the few years that Violet studied at IISc, she lived with her parents. “There were students from all over India, but mainly South Indians,” she says. Outside the classroom, men and women mixed freely, forming music clubs, playing bridge, and going on picnics to Nandi Hills. “At that time, there were people like Homi Bhabha and Vikram Sarabhai visiting the Institute. It was an exciting place because eminent scientists would visit and give talks. It was a momentous time. The freedom movement was in full swing, and students were keen on freedom from British rule.”

“It was a momentous time. The freedom movement was in full swing, and students were keen on freedom from British rule”

But Violet also remembers IISc of the 1940s as being a “caste-ridden” place. “There was a separate Iyer mess and a separate Iyengar mess, and never the twain would meet. Can you imagine, they wouldn’t even eat together?” she asks, laughing. She almost giggles as she recounts how her teacher, Sreenivasaya – “a very orthodox Kannadiga Brahmin” – had to travel abroad and would have to purify himself through elaborate rituals on his return (according to Hindu Vedic texts, sea voyages cause one to lose one’s caste, and hence were once considered taboo). “We used to have terrific arguments about it,” she says, adding that they also “got on wonderfully well. In the end because I always stood up to him, he respected me.” And perhaps it was her influence that brought about a softening of his stand on caste and ritual purity: “Later, he even came to stay at my house and ate my food,” says Violet.

Even as a young woman, Violet had strong opinions. She describes herself as “very much a Commie” during her early days at Lucknow University, influenced by the activism of Ali Jafri and Aruna Asaf Ali, though she says she grew out of it in her late twenties. As a college student, at 18, once she was introduced to Darwin’s theory of evolution, she stopped going to church and became an atheist, which she remains to this day. While studying at Lucknow, she had met a young Punjabi army officer named Vidyaprakash Bajaj through friends. He was later posted in Bangalore, and midway through her time at IISc, she married Bajaj in a simple civil wedding. Her family took the news of her relationship “very badly” at the time, she says with a grin, and none of them attended her wedding.

After she was married, her husband was posted in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and as her parents had moved away from Bangalore, she moved into the Ladies’ hostel at IISc. She says there was “no question” of the caste divisions on campus applying inside the women’s hostel, which had very few students in it – the students had to run the hostel themselves, and organise their own food. It was simple vegetarian fare, says Violet, and everyone ate together. “We were all always in and out of each other’s rooms all the time,” she says, adding that there were none of the restrictions that women in hostels face today. “Isn’t it crazy?” she says of the curfews and unfair rules for women that have spurred protests across the country in recent years.

* * *

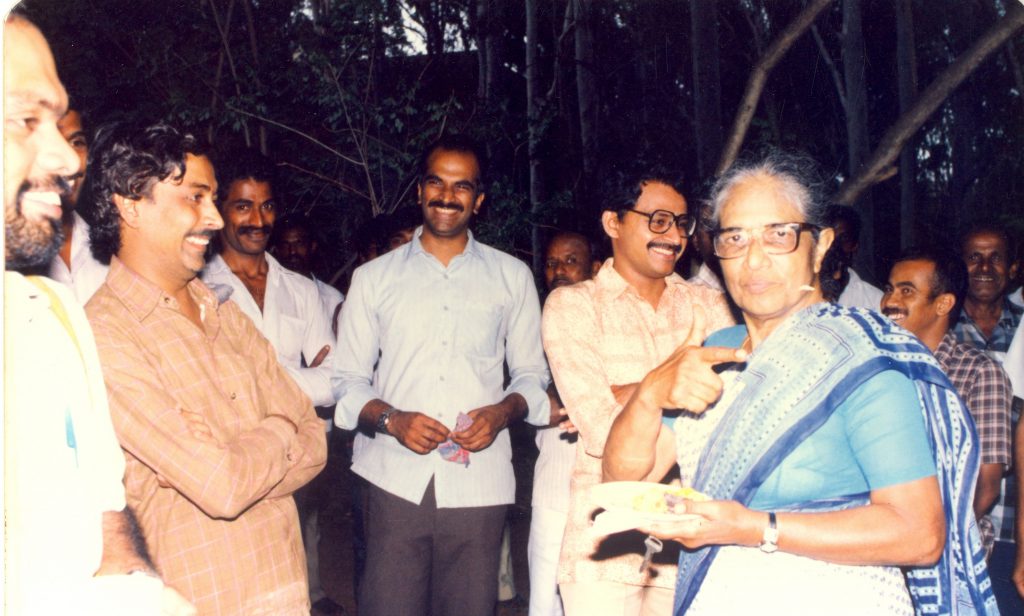

Hostel life helped Violet become more involved in activities at IISc, and brought her closer to her fellow students, with whom she would go on to make lasting friendships. Roshan Irani, Nagamani Kulkarni (née Rao), Indira Bhat (née Gajjar) and Anna Mani were her friends at the time. Nagamani, who studied in the Department of Inorganic and Physical Chemistry, would marry a fellow student at IISc and move to Hyderabad, where she taught Chemistry at a women’s college. Violet says that it was through Nagamani’s family (she would visit them when in Bangalore) that she learned to appreciate South Indian music and dance, and remembers that Nagamani had a sister with a beautiful voice who used to sing Carnatic music on All India Radio. And although she was never close friends with Rajeswari Chatterjee, she remembers her as being a “very nice person”.

Like Nagamani, Indira, who Violet describes as her “dearest friend along with Anna,” married a fellow student at IISc. She had studied biochemistry, and was Reader in Biochemistry at Maulana Azad Medical College in Delhi when Violet worked there for two years as a Research Fellow on a Lady Tata scholarship. (After IISc, Violet had spent a few years moving with her husband to wherever he was posted, including Pune, where she did her PhD before moving to Delhi to be at Maulana Azad.)

Although it was Indira who had been closer to Anna while in college, it was while Violet lived in Pune that she reconnected with Anna and two became best friends later on. Violet remembers Anna from her IISc days as being “still a conservative Malayali” who didn’t socialise much with men. She also remembers that one of the reasons for it might have been the looming shadow of CV Raman, in whose lab Anna worked on the spectroscopy of diamonds and rubies. “CV Raman was inimical to all women who went around with men,” says Violet, who describes him as a “deeply conservative man” who couldn’t stand to see students of different genders mixing.

Violet and Anna met again when Anna was posted to the Department of Meteorology in Pune, and Violet’s husband had been posted to Pune too. “I can’t recall who contacted whom,” she says, but describes the Anna she knew in later years as being “one of the most intelligent people she had ever met,” someone who was “extremely well-read” and had friends all over the world.

“[Anna Mani] didn’t suffer fools gladly. If she didn’t like your company, she made no bones about it”

Of Anna, Violet says, “She didn’t suffer fools gladly. If she didn’t like your company, she made no bones about it.” Her daughter Sheela describes “Auntie Anna” as someone who “wasn’t an easy person, socially”. But Violet also talks about how Anna could be modest and unassuming, and never spoke about herself or what she did. Anna could be generous to her friends, colleagues and domestic help. “To me, she was more than generous,” says Violet, “whenever she had to travel she would always invite me along.” The two made several trips together, such as to Nainital and the Andaman Islands. But Violet laughs as she says the one trip on which she refused to accompany Anna was to China. “She said, ‘Do you want to come?’ I said, ‘Are you mad? Who wants to pay that horrendous airfare?’”

Anna would retire in 1976 as Deputy Director General of the Department of Meteorology, and later set up a private company in Bangalore that made weather instruments, which Violet said she hardly spoke about to other people – Violet herself only knew about it, and Anna’s other activities, much later. “All her charitable works we learned about only after she died” says Violet, who declines to mention what those charitable works were, saying that Anna herself (who died in 2001) wouldn’t have wanted it known.

Violet had a career of her own – she worked at Biochemicals Unit, set up under CSIR, from the 1950s until her retirement. The company’s field was medical biochemical research, and Violet was in charge of quality control of all their products: “I’m good at that,” she says sardonically – “criticising people and rejecting samples.” But she is strangely disingenuous when asked about what she considers her greatest achievement. “Nothing – zero – no achievements,” she says with a shrug. “I’m quite satisfied that I was able to work through my life. And meet my old friends from the Institute through work and renew those friendships.”

Violet worked at Biochemicals Unit, set up under CSIR, from the 1950s until her retirement

Violet admits she was one of few women in the small company. It’s impossible to avoid questions about “women in science”, given that women are still deeply under-represented in several science streams today. Talking about her friends from IISc and their careers, sitting at the desk in her room on the day of our last interview, I ask, did they never feel that they were pioneers, entering fields not considered common for women to be in at the time? Did it not feel like they were doing something important and wonderful, that was of historical significance? “No,” she says simply, with a shrug, uncomfortable with the idea of being seen as special. One night over dinner at her house, Violet also said there had never been any discrimination towards women at IISc, barring the example of CV Raman. But on the last day of our interviews, she had more to say about bias against women.

“Definitely there is discrimination,” she says firmly. “They think women are not capable enough to take responsibility. There’s a blatant prejudice against women. They say, the man has his family, so he is more deserving than a woman. It shouldn’t make a difference if she is married or not, if she has children or not. What if you don’t have children, but have elderly parents to look after?” she asks, echoing some of the questions that have been raised often by those protesting against the reasons that force women to drop out of science. Violet is quick to clarify that she has never been discriminated against herself (not unlike Anna Mani, who according to Abha Sur didn’t seem upset that she had been denied a PhD herself after her years of work at IISc, but was angry on her friend Sunanda Bai’s behalf), but that what she says refers to “a general attitude, an institutional attitude”. “If you have men and a few women in a department in an institution, the man will get the preference for any job promotion, don’t you think so?”

* * *

When I tell Violet that IISc these days has daycares for children on campus, she says jokingly, “I’m in need of a daycare centre.” Later, she says, “It’s not pleasant to live to be 101 and have to depend on others. I like my independence, I like doing things my way. I’m a difficult person to please.” Until two years ago, she was far more active and mobile, even checking and responding regularly to emails, until a bout of chikungunya took its toll.

Her daughter Sheela describes her a “toughie”, saying, “they don’t make women like that anymore.” She remembers the years in her childhood when her mother couldn’t work because her father was transferred often. “She would turn the kitchen into her laboratory – if she couldn’t do science outside, she would do it at home, telling us about the chemicals responsible for keeping a soufflé stiff…she was an excellent cook,” she says. Violet insists that she hated cooking. Sheela, a retired professor of economics, recalls that when she got married, her mother warned her to never let her in-laws know that she knew how to make chapatis, and advised her not to “clutter her life with children”. When talking about society’s expectations in terms of adhering to religion, caste, and gender roles, Violet says, “Imagine living your whole life being loaded with all those customs! I’m so free!”

“Interesting life I’ve led,” Violet says that night in her room after an evening of reminiscing, both with wonder and satisfaction. Later, over dinner, when Violet asks Sheela questions about mundane household matters with the same solemnity with which she asks about current affairs, Sheela shakes her head at me, as if to say, “I told you so.” “Mummy and her friends were argumentative, tough, opinionated, difficult women,” she says in mock exasperation, but the admiration in her voice is clear. “They stood by their principles. And they were eccentric. Mummy, would you describe your group as eccentric?” she asks, turning to Violet.

“No,” says Violet quickly, looking almost offended. “We were perfectly normal.”

For more stories in this series, follow these links: