Dead rats forced the Institute to suspend classes in 1937

The first plague pandemic, the Plague of Justinian, ravaged the Eastern Roman Empire killing between 25 and 50 million people in the sixth century. The second, the infamous Black Death, obliterated between 100 and 200 million people in Eurasia in the 1300s. And the third, which had its epicentre in the Yunan province of China, began in the mid-1800s and remained active for over a hundred years. This pandemic killed 10 million in China alone. It spread via Hong Kong to India, where the death toll was at least 12 million even by conservative estimates. Most of these deaths occurred in the late 1890s.

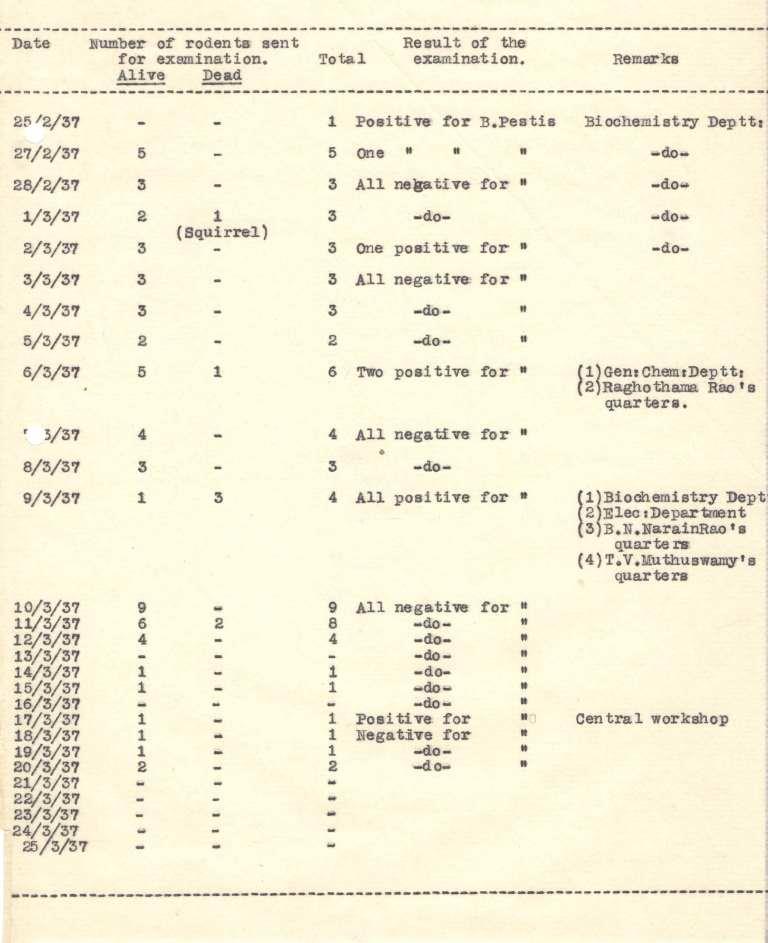

In 1898, the dreaded disease struck Bangalore. This public health crisis prompted the Governments of Mysore and India to take a slew of remedial measures: scores of people were quarantined and inoculated, sanitation and health facilities were revamped, new well-planned extensions like Malleswaram, Basavanagudi, and Frazer Town were developed, Bangalore was divided into wards for better coordination, the Victoria hospital was built, and a health officer was appointed for the city. Some people in the affected neighbourhoods even took it upon themselves to build temples to ward off the disease. One of these, the Shri Plague Maheshwari Temple, still exists in Ulsoor, not far from Blackpalli (now known as Shivajinagar), an area that was particularly badly hit. In the years that followed, the incidence of plague reduced considerably; outbreaks were more localised and infrequent. One such outbreak occurred in and around IISc in 1937. The presence of plague was suspected when dead rats were found on campus and in surrounding villages.

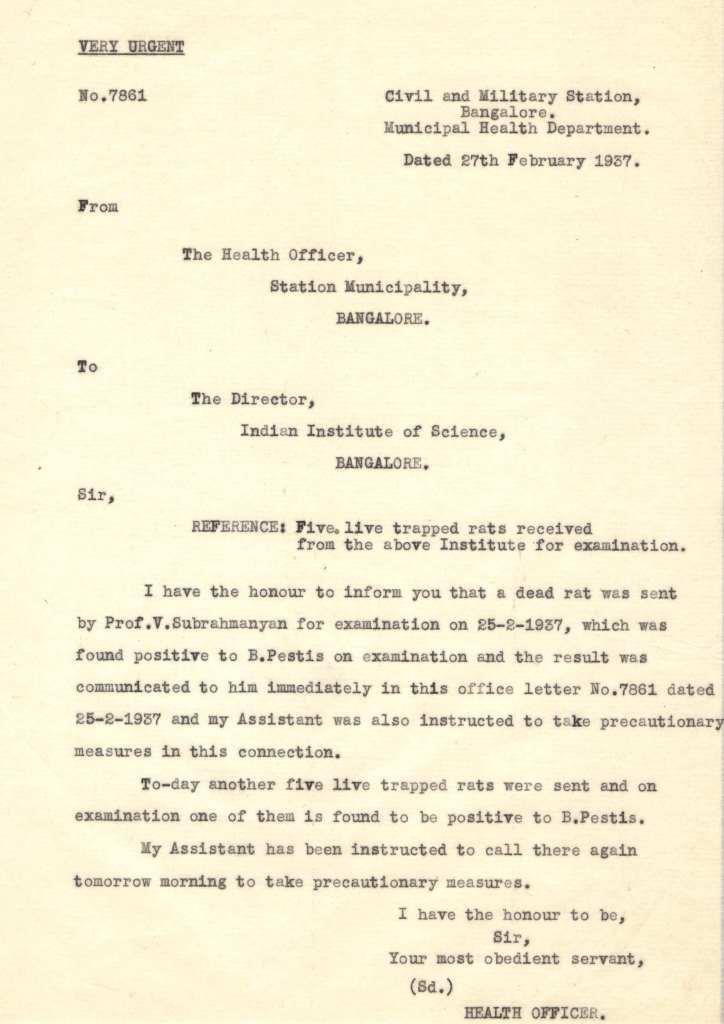

The presence of plague was suspected when dead rats were found on campus and in surrounding villages

Rats have a bad reputation for spreading bubonic plague, the more common version of the disease. But it is in fact transmitted by fleas (pneumonic plague, on the other hand, typically spreads when air-borne plague bacteria are inhaled). However, rats do serve as reservoirs for Yersinia pestis, the bacterium which causes the disease. So rats dropping dead on the streets can send public health officials into a tizzy.

Records indicate that upon receiving the letter and following a discussion with the Health Officer, Raman acted promptly. He issued a directive on 1 March that IISc be evacuated right away. It reads: “The accompanying report received from the Health Officer, Civil and Military Station, Bangalore, makes it clear that the Institute has a rat population which is infected by plague. It has also been brought to the notice of the Director that there has been an influx of rats into the Institute grounds from adjacent infected villages. On discussing the matter with the Health Officer, that the safest and indeed the right course would be to immediately suspend all activities in the Institute and have it evacuated forthwith. All the students residing in the Institute hostel are hereby directed to vacate the hostel forthwith and proceed to their homes.”

Records indicate that upon receiving the letter and following a discussion with the Health Officer, Raman acted promptly

During the break, IISc took other steps to deal with the situation. “Our laboratories are being cleaned and disinfected from day to day. Our workers (staff and students) have all been inoculated,” assures V Subrahmanyan, a professor in the Biochemistry Department, in a letter to the Director on 13 March. Meanwhile, trapping and testing of rats continued. The results were encouraging.

On 25 March, Raman sent a circular to the Institute which says that “there have been no further cases of plague-infected rats during the past few days” and asks the departments to open its doors by the end of the month.

A few days later, on 9 April, with the worst behind them, the Health Officer again wrote to Raman suggesting an intensive campaign against rats to keep IISc plague-free. The “Anti- Rat Campaign” note accompanying the letter recommends hiring separate staff and a supervisor “who should be able to keep a proper record of the rats caught, to keep proper account of traps and the articles and to exercise a general supervision over their work.” It suggests dividing the campus into blocks that are to be attended to systematically. It adds: “All traps, irrespective of whether they have caught rats or not, should be washed by dipping in boiling water and fumigated every time before redistribution. The blocks should be so arranged that each will get its turn for 3 days every fortnight.” The note also lists the number and cost of traps required for a period of one year, and emphasises the importance of “nice attractive baits,” including coconuts, incense, onions, wheat flour and sweet oil.

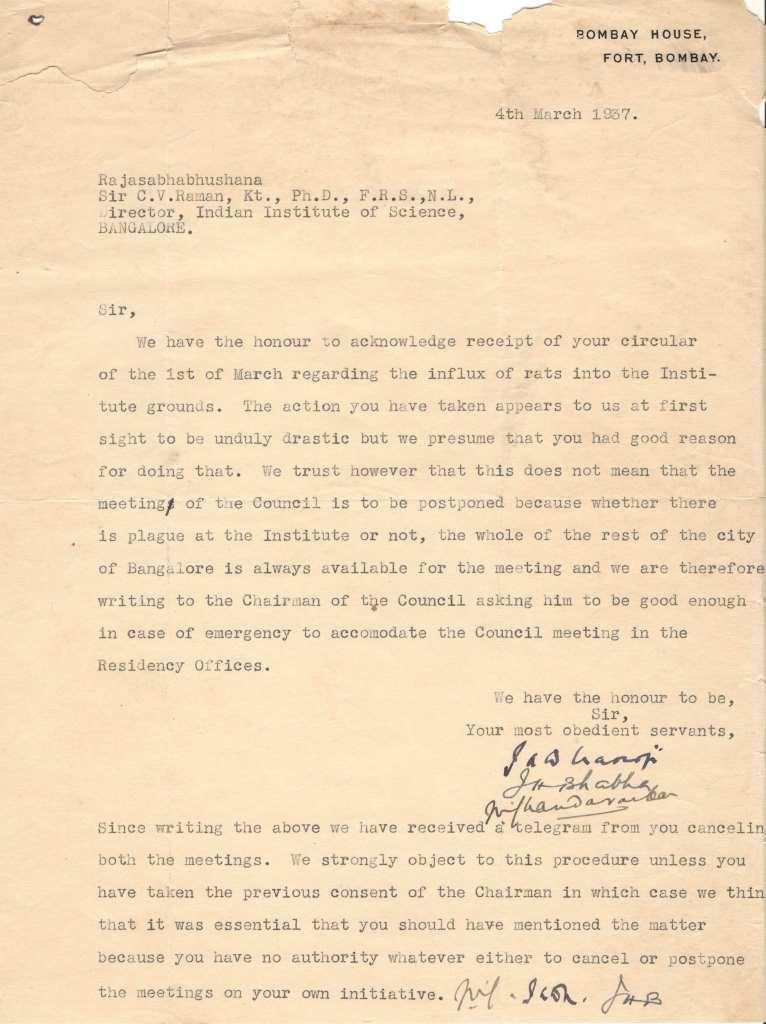

While the plague episode had a happy ending, it was not without controversy. The incident only added to the simmering tensions between Raman and the Council of IISc. In a letter to the Director dated 4 March, three Council members cautiously endorse Raman’s decision to evacuate the Institute: “The action you have taken appears to us at first to be unduly drastic but we presume that you have good reason for doing that.” However, they go on to warn Raman not to postpone the meeting of the Council scheduled for 22 March “because whether there is plague at the Institute or not, the whole of the rest of the city is always available for the meeting.” But before this letter was sent, they received a telegram from Raman saying that he was cancelling the Council meeting. The Council representatives did not take to this kindly. They added an additional paragraph to the original letter rebuking Raman for his unilateral decision. It states: “We strongly object to this procedure unless you have taken the previous consent of the Chairman in which case we think that it was essential that you should have mentioned the matter because you have no authority whatever either to cancel or postpone the meetings on your own initiative.”

While the plague episode had a happy ending, it was not without controversy

It is not clear how Raman responded to the strongly worded letter, but archival records suggest that the Council did not meet in March. The next meeting was held on 3 May. In the days that followed, Raman’s position as Director became untenable and he eventually stepped down. His resignation was accepted at an “Extraordinary Meeting” of the Council held on 1 June.