How creative pursuits open up new vistas for scientific exploration

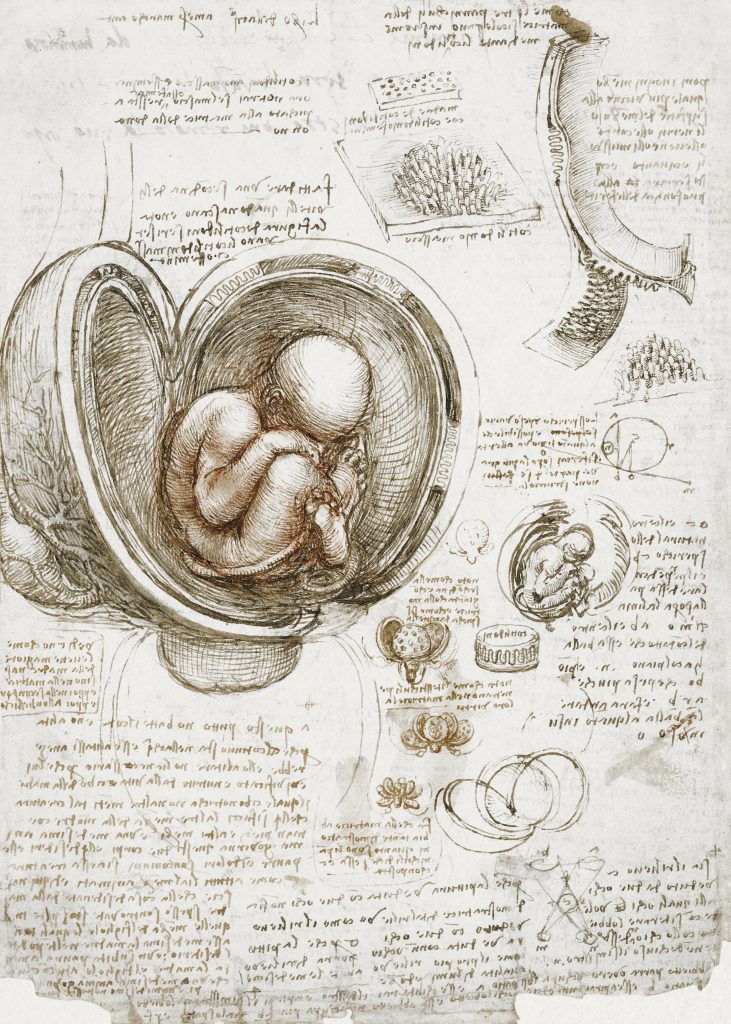

On a sunny day in the 1600s, in the picturesque town of Lombardy, Italy, an artist was busy at work in a hospital. This might sound strange, but it was a perfectly ordinary occurrence in the life of Leonardo da Vinci. The fifty-something-year-old was studying anatomy at the University of Pavia, observing the human body’s inner workings and drawing them in careful detail. He filled his notebooks with over 200 diagrams of the heart, bones, and other organs, accompanied by precise notes. But it would be decades before the world realised the true value of these figures. While the surviving drawings were collected and preserved separately, most of his anatomical studies were used to inform principles and rules for anatomical sketching, compiled in his book, A Treatise on Painting (1651).

Today, Leonardo is renowned worldwide as an artist, the person who created some of the most famous paintings in the world. But few know that he was also a man of science. Inspired by everything from human emotions to bird flight, he was a prolific scientific illustrator, engineer, and researcher who studied machines and men with equal zeal. Alongside the many Renaissance paintings he’s known for, he also designed inventions like the earliest forms of aeroplanes, bridges, war machines, and even a keyboard-like musical instrument.

It’s hard to say if Leonardo was more of an artist or a scientist. But it is clear that he was endlessly curious about the world and adept at blurring the lines between disciplines, as have many others before, during, and since his time. Take, for example, Richard Feynman. The Nobel Prize-winning physicist found deep fulfilment in painting, which he called “an appreciation of the mathematical beauty of nature, of how she (nature) works inside.’’

Scientists are exploring various art forms to think, feel, and understand science differently

Since the dawn of civilisation, art, music, and storytelling have been integral aspects of being human. While not everyone claims to be an artist, most of us have, at some point, turned to creative expression – doodling during lectures or scribbling angsty poetry to navigate the growing pains of adolescence. Creativity seems to be an intrinsic feature of being human, and scientists, too, are exploring various art forms to think, feel, and understand science differently.

“Philosophy has had a big influence on my scientific thinking,” says Partha Ghose, a Kolkata-based physicist who practices several arts like writing, theatre, and music. “I’ve always drawn deep inspiration from Rabindranath Tagore’s songs – especially the ones about nature and our place in it. They remind me that science is just one way of engaging with the world.”

For behavioural ecologist Sambita Modak, the arts are inseparable from scientific inquiry. “An early exposure to the works of Leonardo da Vinci played a vital role in my interest in the art and science of observation and inquiry, which most likely explains my current interest at the intersection of art, science, and technology,” she says. An alumna of the Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES), IISc, Sambita works at the intersection of ecology and art, translating her understanding of the natural world to the latter. “Art initially served as a refuge for introspection, self-regulation and grounding, but it also sharpened qualities essential to science, such as patience, close and inquiry-driven observation, and a willingness to experiment,” she says.

Parallel processes

Sambita began experimenting with art right from the age of four. Her interest in science developed in parallel, encouraged by a family that fed her curiosity with books about both worlds. That dual interest guided her all the way to a PhD in behavioural ecology, and, by the end of it, a desire to unite her love for art and ecology in a space where the two could deepen one another. “I think it ultimately boils down to the childhood dream of unravelling the secrets of the universe, to understand the world around us better – from natural processes and patterns of the world around to the human life and psyche,” she says.

Over the past few years, she has found interesting parallels in her art and scientific processes. “The choice of tools or medium [for my artwork] is primarily determined by the subject or intent of the creative project, much like [how] the scientific question determines the study method, setup, analytical approaches, and so on,” she explains. For example, for commissioned projects involving scientific or wildlife illustrations, she uses digital tools as they allow for easier revisions and tracking versions of an artwork through its progress. In contrast, for quick live drawings in the field, she prefers pen and brush on paper.

Sambita also draws inspiration from other artist-scientists, literary works and movements, like the Oulipo movement, a French method of exploring mathematical rules applied to literature. One example of this is the lipogram, or writing without using a specific letter. A 2001 book inspired by this concept, Ella Minnow Pea, is a fascinating example. The story follows a series of letters between characters who live on a fictional island called Nollop, as they have to progressively discard using various alphabets banned by the government.

While the members of the Oulipo movement remain an exclusive society, the intersection of maths and art has a long history, and especially in an Indian context – in the ancient practice of classical music.

Of course, music has no boundaries and there are infinite traditions in a country brimming with cultural diversity. But what is understood to be ‘Indian classical music’ takes two major forms – Carnatic, of southern India, and Hindustani, of northern India. Both boast of a long interwoven philosophy of technicality and creativity. The arrangements of the ragas, an exclusive concept of Southeast Asian music (which American musician Walter Kaufmann said “cannot be explained in one or two sentences”), follow rules of their own. Mathematical arrangements and constraints of various notes differentiate ragas from each other, yet there is space in between for free composition.

‘Music is my solace and a source of creativity that powers my professional life as a scientist’

It’s this blend of discipline and imagination that drew Debojyoti Chakraborty to the world of Indian classical music. “Music is my solace and a source of creativity that powers my professional life as a scientist,” says Debojyoti, a scientist at CSIR-IGIB, New Delhi, and a lifelong sitar player. He believes that the mathematical underpinnings of both art and science bring about a shared understanding of their technical aspects. “Scientific logic and hypothesis-driven questioning have taught me the importance of approaching Indian classical music from an analytical point of view,” he adds.

Debojyoti believes that Indian classical music has two hardcore components – technical virtuosity, where the musician hones his skills through rigour, discipline and practice; and spontaneous creativity, which comes with lifelong listening, imbibing, learning, researching and contemplating. “If you ask me, both these components are necessary to be a good scientist as well. Rigour and problem-solving are daily aspects of experimental research, and I find a lot of similarities in how I approach music and science,” he adds. “Just like how, as a musician, I am enthralled by the numerous possibilities of elaborating a raag or taal, my mindset in approaching a scientific problem is guided by the acceptance that several alternate theories always exist for coming to a solution, and these need to be experimentally validated.”

Sambita echoes this sentiment. “I believe the artist’s sensitivity to patterns – spotting both trends and outliers – closely parallels the analytical skills expected of scientists. In that sense, creating art parallels some aspects of designing a scientific study: a cycle of observing, questioning, experimenting, interpreting, and producing a shareable output.”

The language of science

Visit your closest library. Most likely, there are books that tug at your nostalgia with their cream covers and cosy animals. The Tale of Peter Rabbit and other such works in the series were a labour of love by Beatrix Potter, an English author with a deep love for the countryside (so much so that she purchased and owned lands there just to preserve them). Beatrix was also a gifted mycologist and science illustrator, and loved studying almost all branches of the natural sciences out of sheer curiosity. Limited by the constraints placed on Victorian women, she still managed to study fungi as an amateur and gave the world illustrations that are still referenced today.

In contrast, Maria Sybilla Merian was a German scientist and artist whose illustrations revolutionised the field of entomology, or the study of insects. She utilised her artistic education to write two books and document the life cycles of more than 150 insect species. Before then, the prevalent view about insects was that they spontaneously generated from mud or other nonliving parts of nature. Her books were fundamental in understanding how insects grow, live, and reproduce.

A growing number of scientists are now using their art to communicate science

Like her, a growing number of scientists are now more intentional than Beatrix in using their art to communicate science. Creative power is how scientific ideas are untangled, and it is what helps make these ideas more accessible to scientists and non-scientists alike.

“After many years of trying to communicate science – often with only modest success – I have realised something important: most lay readers, for whom much of this effort is intended, instinctively shy away from technicalities, abstractions, and even the simplest calculations. This is the “Two Cultures” divide,” says Ghose, who has extensive experience in filmmaking, producing documentaries, and has authored several books on science communication.

The “Two Cultures” divide is a concept put forward by scientist-novelist CP Snow, addressing the alienation of science and the humanities. He believed that a polarisation between the two fields was holding progress back. “If we wish to bridge it,” Ghose continues, “we must speak in the language they find most natural and inviting – the language of literature. The best science communicators have always known this. Technicalities build walls; stories build bridges.”

“For me, art sharpens scientific understanding while also opening new ways of engaging wider audiences with ecological and scientific ideas,” adds Sambita, who has found new ways to engage with people through installations, and has organised workshops around coexistence with species

Democratising science through art

In recent years, there has been an uptick in events, festivals, and exhibits designed to bring science to the public, like the ‘Art of Science’ at Binghamton University or ‘Cosmic Titans: Art, Science, and the Quantum Universe’ at the University of Nottingham, held this past year. Closer home in India, institutions like the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research and the Nehru Science Centre host art outreach programmes in various forms.

Science Gallery Bengaluru is one of the few institutions in the world dedicated to an artistic exploration of science. Along with displays of scientific concepts, they host a year-long exhibition centred on a broad scientific topic and its relation to the world at large. This year’s exhibit, “Calorie”, explores links that nutrition and health have to history, politics, psychology, and the environment, conveyed through art exhibits and interactive events. They are also involved in outreach programmes like the “Experimentors”, a mentorship initiative to train young adults in interdisciplinary science-art initiatives and help them engage with visitors.

“It’s about becoming a bridge between visitors and the idea behind the works being presented,” says Tejashree V, an Experimentor currently at the Science Gallery. “We are trained by scientists, researchers, and artists, and being here is recognising that art and science go hand in hand.”

“Simply the act of everyday conversation makes not only the visitors understand the scientific themes more deeply, but us too,” adds Vinaya Krishnan, another Experimentor.

Art can make or break what science looks like to the public

Art, being a reflection of human society’s desires and fears at a specific time period, can make or break what science looks like to the public. Medical dramas like Grey’s Anatomy inspired people to become doctors. Interstellar’s popularity set the stage for countless conversations and increased public interest in space and quantum physics. Indian films like Mission Mangal have served as powerful tools to convey aspects of rocket science to everyone, regardless of the depth of their knowledge in those fields.

Without understanding, there is ignorance and fear. The anti-science movement currently spreading across the USA is a sad example of what happens when people stop believing in or are misinformed about scientific advancements. The use of art to convey science in a democratic, understandable, and interesting way can serve as a critical factor in increasing public participation in decision-making related to science and research.

Art and science will always be two branches of the same idea – a desire to explore and understand the mysteries of this world. They are the two arms reaching out into the abyss of ignorance, looking for the light of knowledge. In Ghose’s words, “Together, they give us a fuller, richer picture of reality.”

Yashashree Prabhune is a fourth year BTech student at DY Patil University, Navi Mumbai, and a science writing intern at the Office of Communications

(Edited by Abinaya Kalyanasundaram, Ranjini Raghunath)