How NS Govinda Rao laid the foundation for civil engineering

A photo of a moustachioed bespectacled man looks down from the wall of the office of the Department of Civil Engineering at IISc. A few steps further, in the Chairperson’s office, another portrait watches on from above the door. It is fitting that NS Govinda Rao has a watchful eye on the department’s proceedings and decision-making. Although the man never worked in these offices (he sat in room number 303 of the Department of Electrical Engineering), Rao played a pivotal role in the nurturing and growth of the Department of Civil Engineering. It has been more than half a century since Rao left the department, but his name still reverberates in these halls, kept alive by those who knew him and others who know of him.

There are stories of Rao’s benevolence, of his love for science, and justified anger. Tales of Rao calling the Registrar and demanding that he sort out a clerical error regarding a student’s nonpayment of tuition fee, and slamming the phone receiver (The red tape was cut immediately). Other chronicles talk of Rao securing money and scholarships for his students out of thin air. There are several more interesting tales, many are true, others made true apocryphally. The picture that is painted is that of a man who was accomplished, capable, and humane. He was also the reason the Department of Civil Engineering became a cornerstone of the Institute.

From industry to the Institute

Rao was born on 6 February 1907 to Radha Bai and NK Srinivasa Rao in a high-achieving family in Mysore city, to which place his great-grandmother had migrated from the small Maharashtra town of Naladurga in 1860. His great-grandfather was the deputy commissioner, and his father a high court judge. As the second child with five sisters, Rao had the environment and aptitude for academic excellence, influenced by his father’s intellectual pursuits that extended to mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, and agriculture, among others. After he completed his BE with honors from Mysore University in 1928 (he secured the first rank and two gold medals), he eventually joined the Public Works Department as an assistant engineer.

Govinda Rao worked extensively on cavitation, siphons, and other areas of hydraulics, and also pioneered research in soil dynamics

Rao was jarringly thrust into the real world when he lost his father and had to shoulder the responsibility of his family at the young age of 24. Despite personal hurdles, Rao grew in his career. He worked extensively on cavitation, siphons, and other areas of hydraulics, and he also pioneered research in the area of soil dynamics.

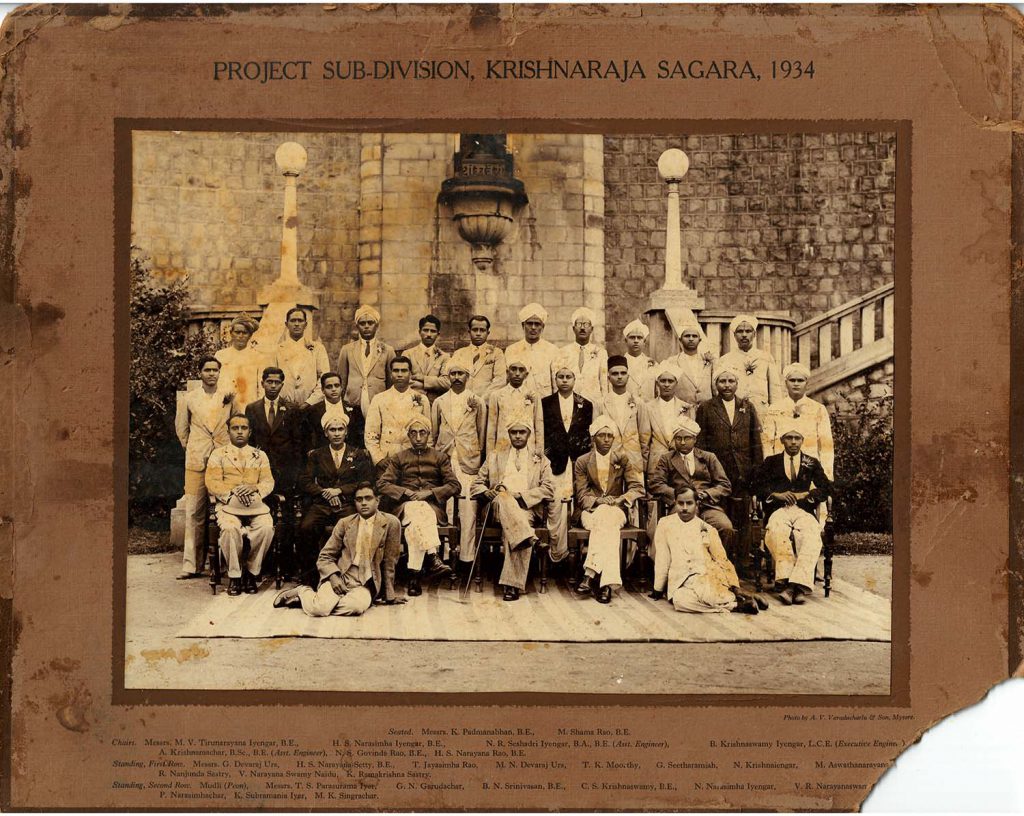

He played a major role in the survey, design, and construction of several irrigation projects such as the Krishnarajasagar Dam, Visvesvaraya Canal, and Markandeya Dam. He also taught at the Government Engineering Diploma School in Bangalore for two years. In 1945, he became the Assistant Director of the Karnataka Engineering Research Station (KRS), Krishnarajasagara.

His elevation at his work was the result of his nearly two decades of research publications, particularly his association in the design of the Ganesh Iyer Siphon, which is a special kind of domed volute siphon that ensures excess inflow into a reservoir. This gave him a reputation as a leading voice in hydraulics research and caught the eye of celebrity engineer M Visvesvaraya. It is said that it was upon Visvesvaraya’s recommendation that the then IISc director, MS Thacker, appointed Rao as the head of the Civil and Hydraulic Engineering section, which was established as part of the Department of Power Engineering in 1950.

It was a time of great turmoil and flux. The country was thrust into independence and was trying to find its feet. Power and water were major areas of focus, and several structural, geotechnical, and hydraulic problems needed to be solved for the smooth functioning of the country. Rao was seen as an ideal candidate because he married industry knowledge with academic rigour. Though he did not have a doctorate to his name, his research during his time in the KRS Research Station had shown that he had the aptitude to lead a department.

Under his watch, the Civil and Hydraulic Engineering section grew and became the Department of Civil Engineering in 1972, five years after he retired. He developed three research streams within the department – Water Resources, Structural Engineering, and Geotechnical Engineering. He also started Master’s programmes in Power Engineering, and Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering. His tenure saw several degrees awarded and many research papers published in leading national and international journals. The department grew from strength to strength and was recognised as a Centre for Advanced Studies by the University Grants Commission, in recognition of the quality of work that came out from the department led by Rao.

The visionary “non-academic”

Rao was a curious and capable researcher. He published over 100 papers in reputed journals and frequently attended international conferences. His significant contributions were in the areas of cavitation, laminar and turbulent flows, flood adsorption, design of dams and canals, siphons, and more. He also served as the editor of the Journal of the Civil Engineering Division, published by the Institution of Engineers between 1962 and 1965, and as a member of the panel of editors for Hydraulic Research published by the International Association for Hydraulic Research in 1963. In 1965, he was elected president of the Institution of Engineers, and the Indian Society of Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering.

As good as Rao was at science, he was perhaps a better administrator

As good as Rao was at science, he wasperhaps a better administrator. The Civil and Hydraulic Engineering section at IISc started with fewer than a dozen people. To build it, he needed workforce, expertise, and finances. The finances were straightforward. He dug into his little black book, which had several contacts from his years in government service.

At the Institute, there was plenty of technical know-how. This, combined with Rao’s ability to consider real-world impact and outreach, turned out to be a fruitful union. Being a “non-academic” in an academic institute, as he frequently quipped, he was able to make the best of both worlds.

“His contacts in the Central Board of Irrigation and Power (CBIP) got him projects [to work on]. Then, he could get students into the department under the CBIP scheme. He built the department through the CBIP schemes,” says KS Subba Rao, former professor in the department.

“The civil department had a lot of money because of the projects they were involved in,” says K Chandrasekara, former professor of structural engineering at IISc. “Rao’s contacts within the government and his rapport with people helped a lot with getting projects, consultancies for dams and other works, and funding.”

With the finances sorted, Rao built up a department filled with capable scientists. He encouraged his team to build equipment and was willing to fund it. The high-speed closed-jet water tunnel facility, the first of its kind in India, was designed, fabricated, and established due to Rao’s vision, which helped with research in cavitation. “He travelled around the world to learn how to build it, and finally it was built based on a design from Caltech (California Institute of Technology),” says Rama Prasad, another faculty member in the department at the time. The reason for choosing the design was that it was the most suitable for the rocky crust found in the Institute.

The hydraulics laboratory was also built during his time. Research around soil mechanics, hydraulics, and structural engineering developed with his active support.

Leaving behind a legacy

Rao maintained an open-door policy in his office. When KS Jagadish, a former student of Rao’s in 1961 who later became a professor of structural engineering at the department, approached him to change his area of interest, Rao was highly encouraging. “He was very open-minded that way,” Jagadish admits. With the department having an interdisciplinary feel to it since its inception, thanks to its close association with power engineering, Rao encouraged his students to seek advice from other heads of departments and even director Satish Dhawan himself.

Rao had an eye for talent and was not averse to accommodating talent that he spotted to the advantage of the system. One anecdotal story talks about Rao encouraging a student who had received a second-class rank in his Bachelor of Engineering degree to author a research paper and publish it in the Journal of Institution of Engineers (India), upon which he was promptly admitted to a research programme in the department.

He taught students to learn, encouraged them to believe in their research, and to speak out’

His students also remember him as a teacher who went beyond books. “He taught students to learn, encouraged them to believe in their research, and to speak out. He also promoted student activities,” says S Vedula, a former faculty at the department.

Once part of his department, everyone was treated as an extended family. Conceivably, the role of the patriarch came to him naturally, having had to take over as the head of the family at an early age and then having a family of nine children himself. His daughter describes him as a loving, approachable, and present father. “He was a great storyteller … talkative, easygoing. All the children found him approachable and he never lost his temper,” says Vatsala Ramamurthy, his daughter.

His love for animals and gardening also shows a certain want to nurture. Due to his extended family, dinner time attendance sometimes hit more than two dozen people in the kitchen.

In one instance, when one of the department’s faculty members was given a promotion over the others, he was able to placate the irate parties by securing them scholarships for higher studies in foreign universities. The benefits were two-fold, it ensured harmony in the department and more knowledge as well.

When Rao retired in 1967, the funds and schemes from CBIP also slowly waned, but the department had already established itself as a powerhouse and was more than capable of standing on its own. Since then, the department has grown rapidly, spawning several groups, laboratories, and branches, and contributing to several nation-building projects that are shaping the country. Though the current department might be far from the one Rao was familiar with, he remains a central figure in its collective memory, commemorated by the bi-annual Prof NS Govinda Rao Memorial Lectures held on his birth anniversary.

Rao passed away on 22 December 1995. In his long journey, he was known for multiple pursuits. Following his retirement, he served as an advisor to the CBIP till 1971. He was invited to various countries, such as Australia and Germany, to deliver specialist lectures. He was also a member and consultant for various bodies in the power and infrastructure field, even serving as the president of a few, such as the Indian Geotechnical Society and the Institution of Engineers (India). But perhaps one of his most lasting legacies is building the core of what would make IISc’s department of civil engineering.

Subba Rao emphasises: “A department of civil engineering research was almost unheard of [at the time]. That was his vision.”

(Edited by Rohini Subrahmanyam, Abinaya Kalyanasundaram)