Digitisation helps preserve valuable material as well as provide access to it. But getting there and beyond can be a thorny process

As staff in an archive, if there’s one thing we learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, it is how important digitised material can be to researchers. With lockdowns and several travel restrictions in place after March 2020, the only way we at the IISc Archives could continue to respond to most requests from researchers was to digitise the documents they needed, if this was possible. We weren’t the only ones: archives across the world found themselves fast-tracking work on creating or improving online access to their documents. Sounds simple enough, and seems like an obvious step for archives. But getting there can be a thorny process.

There are plenty of great reasons to digitise archival material, and perhaps the most important one is preservation. Physical material can be threatened by floods, fire, earthquakes and other disasters. And recent events like Russia’s war with Ukraine have shown that institutions like archives and the material they hold can also be damaged or destroyed in times of civil unrest and international conflict. Making digital copies of archival material is a way of safeguarding its future, especially since these can be stored in multiple locations (like in cloud storage, where the server needn’t be physically located in the same place as the archive).

Setting catastrophes aside, even in the daily functioning of an archive, users can be shown a digital copy, which means that the original won’t need to be handled each time. If a document is already fragile and likely to deteriorate each time you have to pull it out and place it back in its container, having a digital copy can go a long way towards its preservation.

The other key reason why archives choose to digitise material is accessibility. Many archives see access as a core purpose, and put in enormous efforts to ensure that their valuable material is made available to people and organisations instead of being locked up in a vault. In one of its resources, the Tate Archive in the UK says that it embarked on digitisation and publication in conjunction with outreach activities to make sure that the collections were “not simply accessible, but accessed”.

Many archives see access as a core purpose, and put in enormous efforts to ensure that their valuable material is made available to people and organisations instead of locked up in a vault

Though not all of our material at the IISc Archives is digitised, having digital copies of certain material that is likely to be requested often, such as Annual Reports or photographs of well-known scientists, has made it easier and quicker to share with users such as journalists or researchers. From an internal perspective, this has also allowed us to minimise the time spent responding to requests, and focus on other essential tasks such as building our catalogue. In an ideal scenario, the more we are able to digitise, the more time we may have to focus on other crucial tasks such as outreach, and processing new material.

A necessity

“For us, digitisation wasn’t a choice, it was a necessity,” says Shubha Chaudhuri, Director of the Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology (ARCE) at the American Institute of Indian Studies in Delhi. As ARCE mainly holds audiovisual material, rather than paper documents, technological updates are a part of its fabric. In the 40 years that she has worked there, their main challenge has been hardware obsolescence: being able to retrieve recordings on open reels, audio and video cassettes, and other analogue formats depends on the availability of equipment to play them back. “Unfortunately, archives don’t rule the market, and the equipment just stopped being made,” she says. While they do preserve the original formats and try to purchase these players – sometimes old instruments that have been repaired and sold abroad on eBay – they still need to migrate to newer formats in order to continue accessing this material.

Maintaining a digital copy, Shubha points out, also helps to retain the audio and video quality. With analogue formats, there would be a ‘master’ version, and copies of it would by default be of poorer quality. There is also the problem of recordings deteriorating with playback (think of the fuzzy moments and warped sound that can come with a videocassette that’s been played too many times). With digitisation, she says, “the first copy is as good as the tenth copy,” and you can play a recording as many times as you like without it causing damage.

However, Shubha highlights the fact that digitisation is a continuous process rather than a one-time affair. “People in [audiovisual] archives learnt a lot about analogue, about its preservation and storage. The big advantage was that if you did it right – if you made your tapes right and you kept your storage facility well, your temperature and humidity was under control, you did your regular checks – you were good. You had your existing collections preserved and you could move on to new ones. And that’s what we’ve lost with digitisation – there’s no one-time solution. We have to replace our storage every three years as the hardware and technology become outdated so quickly.” Financially, she says, this is difficult, as is keeping up with digitisation standards and technologies, which change frequently.

Resource intensive

Digitising archival material isn’t quick or easy. Hundreds or thousands of fragile documents need to be scanned and each has to be carefully placed in a scanner manually. Overhead scanners may be required to take images from a height above the document (these are more effective for, say, large bound volumes that may not withstand repeated flattening in a typical flatbed scanner). Large items such as maps may require scanning or photographing in several installments (with the final image being stitched together). Photographing an image using an appropriate perspective, especially if the image is framed and behind a reflective glass pane, takes time and skill. Converting analogue sound recordings to digital ones can take at least as long as the length of the recording itself. Documents with text need to be made searchable using optical character recognition (OCR), and digital copies of archival material need to be checked to ensure they are of a high quality (a blurry scan of a document ends up being of use to no one). All of these require skilled personnel, time and funding – realistically, these are resources that many archives do not have.

Society at IISc, framed behind a glass pane (Photo: IISc Archives/KG Haridasan)

Moreover, obtaining a digital copy is only half the task: ensuring that all digital material is properly structured, accompanied by metadata (including keywords that describe the material, which help users search for and locate it), and mapped to the original, is laborious but necessary. Roland Wittje, Associate Professor in History of Science and Technology at IIT Madras and Principal Investigator of its Archive project, says that without this processing, simply scanning all documents is like taking a bunch of museum objects and throwing them down a well in order to preserve them, and saying to users, “Just take them from there.” He also cautions that it is easy to underestimate the amount of data that can be processed. Large government archives that he has seen in Europe, for instance, have “endless” data, he says. “To think that you can digitise it all [indicates a failure to] understand the amount of data there really is.”

There’s also the question of archiving material that is “born digital” – material that was created in the digital age, such as emails, or digital photographs. Archiving it is a challenge, Roland points out, as we create so much more digital material. Where earlier we might have thought twice about writing a letter, we now send so many more emails and messages on social media than is strictly necessary. “Anyone who has tried to archive their own email account knows what hell that is!” he says.

‘Anyone who has tried to archive their own email account knows what hell that is!’

Whether digitised or born digital, managing this material still requires equipment for storage, scheduling periodic online backups, maintaining servers, adequate trained staff, and – though this may sound surprising – backups on tape or hard drives if necessary. Magnetic tape, which was once used for analogue storage in archives, appears to have evolved today into a practical tool for digital preservation. In 2018, Mark Lantz of the IBM Research–Zurich lab wrote in IEEE Spectrum that magnetic tape was still the future of data storage: though the speed of access was slower than a hard drive or semiconductor device, he argued that it didn’t consume power (after the data was recorded), it was reliable, relatively secure against cyber attacks, cheaper, and could store more data than hard disks.

In 2020, IBM and Fujifilm teamed up to make a magnetic tape cartridge that could hold 580 terabytes (TB) of data, and was small enough to fit in the palm of one’s hand. “Just to put that in perspective,” IBM announced in a press release about the product, “580 TB is equivalent to 786,977 CDs stacked 944 meters high, which is taller than Burj Kalifa, the world’s tallest building.” But why would one need physical backup when cloud storage is available? Mark Lantz mentions an incident in 2011 when Google accidentally deleted saved emails in about 40,000 Gmail accounts, and was able to restore the data because it was backed up on magnetic tape.

Managing digital storage is a complicated enough task that some institutions outsource it, just as some archives hire private vendors to do the job of digitising. For example, the Endangered Languages Archive (ELAR) in Berlin, Germany, which has material from around 600 languages (including 30 from India), is a digital archive based on a commercial system called Preservica to ensure a reliable digital repository solution, including workflows for format conversion, migration and backups.

Ethical questions

Apart from the logistical challenges that digitisation poses, there are several ethical questions that accompany blanket policies to digitise material. Shubha, whose fieldwork as a researcher has involved interacting with performers and community folk artists, says that because digital copies of recordings are easily shared, they are also easily downloaded and distributed or monetised without permission, which violates the intellectual property rights of performers. She also talks about scenarios she’s encountered in which users don’t always honour agreements to use digital material solely for their stated purpose, or don’t always reuse material in a way that is respectful to communities and individuals (she recalls a user offering to connect ARCE to a nightclub in London to sell their footage of a “possessed” woman in a village in Rajasthan). Unauthorised sharing of material can break a donor’s trust in the archive, Shubha says, as putting digital material online is akin to publishing – something the donor didn’t necessarily sign up for when depositing material in an archive. Farah Yameen, an independent researcher, archivist and oral historian, points out that digitisation and public access is often a condition of funding – an aspect that complicates an archive’s decision to digitise or not digitise.

Aside from issues of copyright, when material is digitised selectively, there is also the question of where the resources should be invested – and what suffers in the bargain. Roland says, “During COVID-19, we learned that everything that is accessible online will be used more. Historians need to think very carefully about why they are doing that – they are creating new kinds of hierarchies while upholding old ones.” He points out that a science archive would be more likely to make the papers of someone famous like Charles Darwin, or a Nobel laureate, accessible online. Historians tend to focus only on this material and end up making well-known scientists even more prominent in their writing, while ignoring those who may not have material about them available online. “It’s as though if something doesn’t exist on the internet, it doesn’t exist at all. [For an archive] it’s an ethical question: which repositories do you make available and which ones do you not?”

“People are right when they say we cannot avoid the digital,” says Roland, but he is skeptical of the efficacy of efforts to manage material after it has been digitised: “I am just saying that so far we haven’t been very good at it.” And ultimately, he says, we still need the original physical documents to refer to: “It’s not just about scanning – there are a lot of layers on the document.” In a blog post about why archives don’t digitise all of their material, Samantha Thompson, archivist at Canada’s Region of Peel Archives, writes that digital copies don’t completely capture physical characteristics (like thickness and type of paper, or marks of wear, which convey illuminating information) or context (like sticky notes, which may contain information relevant to the document on which they are stuck, but also obscure a portion of the document). “The digital copy is not a true copy, right? The only true copy of the original is the original,” Roland says with a laugh.

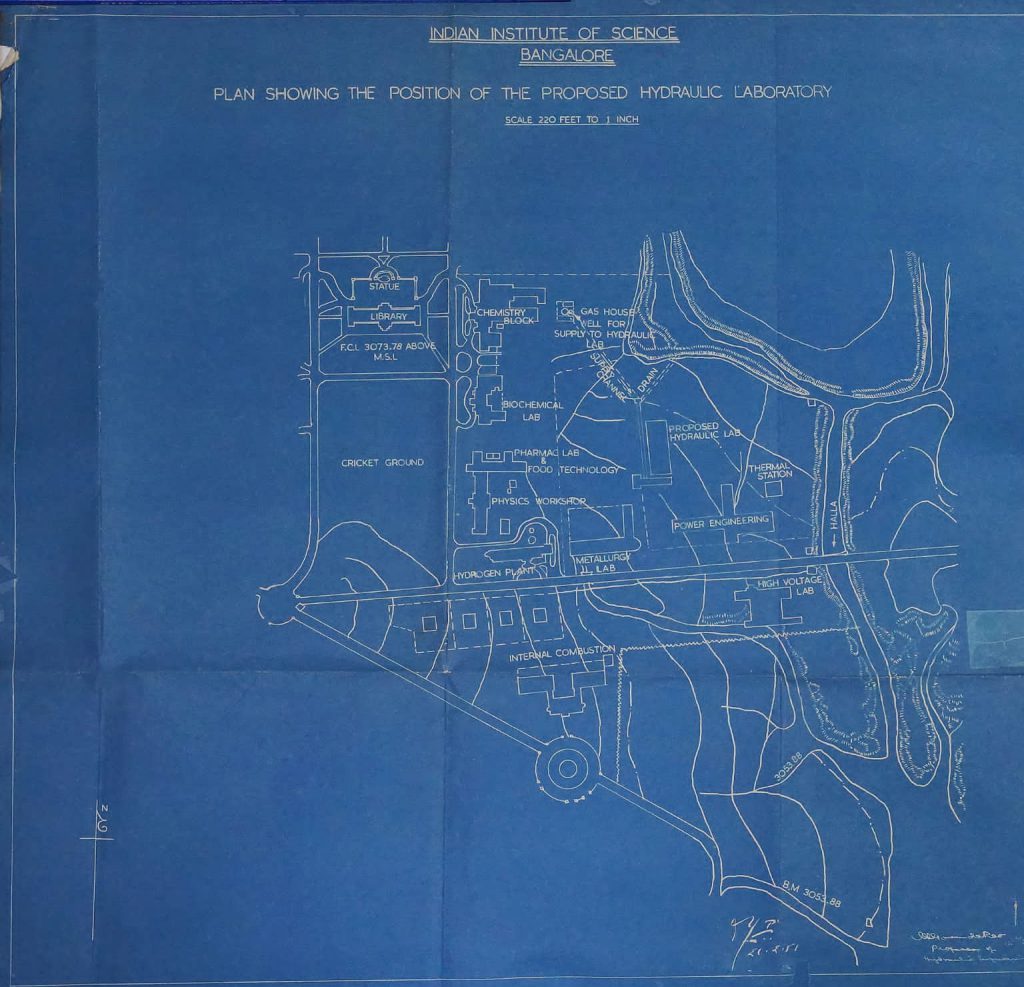

Even so, many archives still push forward with digitisation plans and workflows, and at the IISc Archives, we hope to do so too. Perhaps the most time and effort that we put into digitising a single document so far was in 2021 when the Department of Mechanical Engineering requested a copy of a map of IISc’s campus from 1951, to be used in a publication commemorating the department’s 75th anniversary. The map was too big for the scanners we had at the time and was creased across its length and breadth because of the way it had originally been stored. After some attempts (with limited results) to flatten the document as best we could, we spread it on the floor over sheets of acid-free paper and weighed down the edges while photographer KG Haridasan stood above it, perched precariously with one foot on a table and another on a chair, so that the photograph could be taken from a height and under suitable lighting. We did our best in response to an urgent request, but we hope to have the opportunity for a do-over in the future. It’s worth the effort: archives are meant to last across the ages, and if our physical material doesn’t survive, at least we’ll have the next best thing in line.