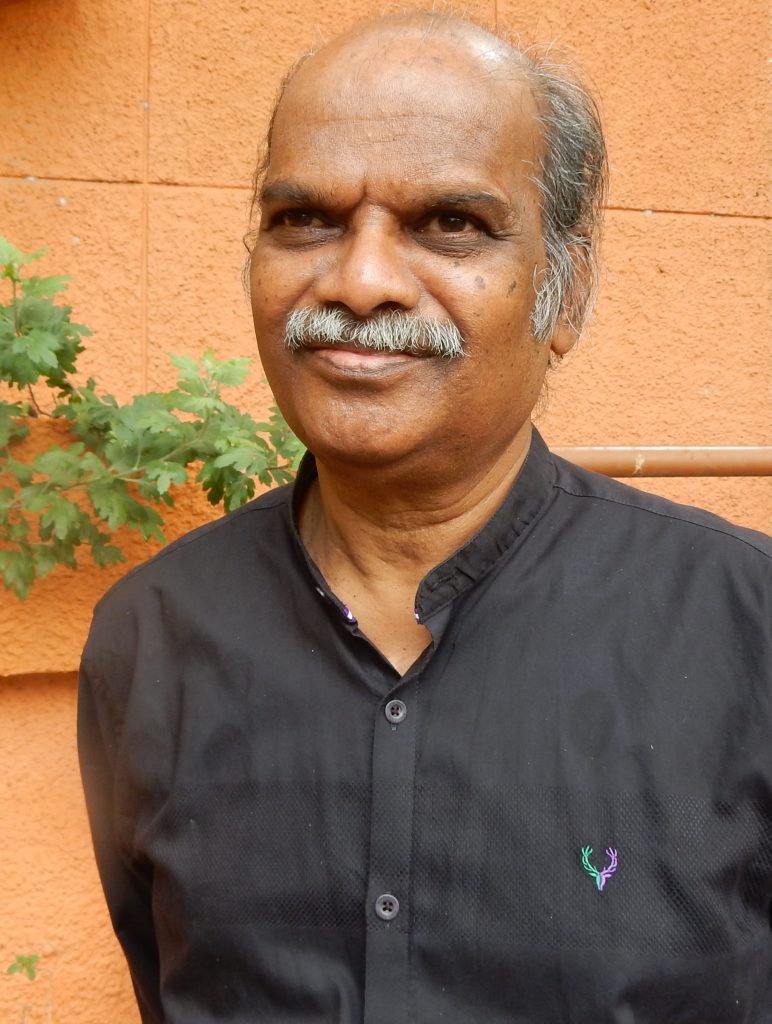

When VC Amanan joined IISc in 1980, he was 26 years old. He had wanted to be a scientist, and applied to the Government Arts and Science College near KR Circle for a course in Chemistry, Biology and Zoology. But as luck would have it, he missed the interview for the seat as the letter summoning him arrived too late. He began a diploma in mechanical engineering, abandoned it to study in a catering college, worked for some time at Hotel Ashok, and wrote an exam to become a clerk. Then in 1979, his brother spotted an advertisement to work at the mess in IISc. He applied and got the post, and began what would be 37 years of service. In 2007, he was appointed Mess Superintendent, and after he retired in 2015, his employment was extended for two more years on a temporary basis.

He saw IISc’s messes through a period of considerable expansion, from around 300 students spread over three messes in 1980 to four messes with a capacity of 700-800 students each in 2017. Connect interviewed him at his home in Coffee Board Layout about his time at IISc.

What were the messes like when you started working at IISc?

There were three messes in 1980. A – south Indian vegetarian, B – north Indian vegetarian and non-vegetarian and C, the universal mess which served south Indian food, north Indian food, veg and non-veg fare.

You could regularly change which mess you ate in, but many people would join one mess and stay there for 5-6 years. The kind of staff we had at the time made them loyal to the mess. When I joined, most of the staff were very senior, including the cooks and bearers who served the food. And they were very dedicated. They used to take care of the students as if they were their own children. Good, prompt service, no arguments. When I joined, the cost of eating at the mess for each student was around Rs 3 or Rs 3.50 per day!

How have things changed over the years?

In the early years, people with professional experience were hired for the job. I am from a catering background – that’s what I studied in college.

Around 1985, the management began to put restrictions on new recruitments. When the existing employees retired, their positions were not filled. The management started outsourcing those jobs on a contract basis. We had to compromise, and perhaps that led to a slight deterioration in preparation of food. There used to be 120 regular employees in all the messes put together – including supervisors, cooks and bearers. Now there might be around 30.

Employees need a good salary, benefits, job security, and they need to have a sense of belonging and responsibility to do the job well. That’s how things used to be, but now with the contract system, the new people who come in don’t always have proper training or experience, and no job security. It’s a hire and fire system. However, we tried to manage and do our best by giving them [the contract workers] training, and arranging for classes.

We were very liberal about mess timings. Particularly during breakfast in the mornings, which was supposed to end at 9.15 am, but we used to leave it open until 10 am. We did that for quite a long time. But somewhere in 2012 or 2013, we started to be strict about closing on time.

Were there any instances of conflict with the students or management?

Very few. In the 80s, the mess employees went on strike because they thought they were being neglected. But that was resolved very quickly.

In the 90s and 2000s, we started growing very big. By the time I retired three years ago, the average had become around 750 students in each mess. In 2004, they built the new A and B messes where the support staff quarters used to be (the quarters were shifted near Janata Bazaar), and the old A and B messes were given to Nesara and Kabini. The new C and D messes were built in the new hostel complex, with a capacity of around 800 each.

In the 2000s, during admission time, sometimes the food would get over. We would plan everyday to feed around 600 people. But during admissions, we wouldn’t know how many new people would be eating that day – and sometimes we would suddenly have an extra 100-150 people, not including their parents. We usually had a margin of 50 extra people for each meal. During this sudden inflow, we would run out of food – that would create problems and the students would protest. Otherwise, students used to be very cooperative and understanding.

Did you ever take your family to eat at the mess?

No, I didn’t. In fact in the last ten years, except for my weekly day off, I didn’t take casual leave at all. I hardly used any of my LTC [Leave Travel Concession]. Nearly two years worth of my Earned Leave lapsed. [My wife] used to tell me [in frustration], “You have thousands of rooms there. Why don’t you just stay there? When I require you, I will give you a call!”

For any festival, I would have to be there – it would be a big day at the mess, because we would have to prepare

a special lunch and dinner. The mess closed for half a day only on five occasions in a year – Independence day, Republic day, Ganesh Chaturthi, Rajyotsava Day, and a general election. But I enjoyed going around speaking to employees and students at the mess, and having to manage both groups. Those were good times.

Although I’ll tell you one thing – when you are hungry, I cannot argue with you.

Any memories from the mess that will stay with you?

There was a small accident in the new A mess, around 2006 or so. In all the years I have worked here, we have never had a major incident, such as mass food poison- ing or anything like that. But one day, a contract worker switched on the stove for the large steam cooking range, where we would boil milk and rice. He forgot to open the valve to let the steam circulate. Pressure started building within one vessel (which had a double layer for insulation), and it burst. The worker had burns on his chest and stomach and had to be rushed to the hospital by the contractor. It was a very scary and serious problem. That’s why I feel there should be a core group of permanent employees to manage the messes, to ensure that everyone under them is properly trained and so that incidents like this do not happen.

You know, the students from here might have gone to live in the US or UK or elsewhere in the globe. But they still remember our food and when they come back to IISc, they come to us. Sometimes they also eat at the mess – they cannot forget that food. That’s the kind of rapport we developed with the students.

Anyhow. IISc is growing, and I think the messes are doing a good job of catering to the growing number of students. Changes have to happen, no?

For more stories about the mess and accounts by alumni, follow the links below:

A History of the Messes: Dining at IISc

Eating Together: A Student’s Letter of Protest

The Common Dining Hall: ‘Neither Indian Nor European, But Something New’