A brief history of IISc hostels

To the south-west of the IISc Main Building, a stone’s throw away stands a rather squat piece of architecture. The ground floor construction is of grey-brown rock, cut and piled in rectangles of various sizes. The first floor is painted with what must have been a shade of cream, but is now lined with grey streaks of dust.

The building is fortified by an armada of bicycles. Whether they are new and shiny or old and battered (and likely punctured) depends on how much time has passed since a new batch of students came in. To the left of the entrance door – so creaky that it can awaken most of the 200-odd occupants if opened at night – is a white and red sign prohibiting smoking.

To the right, block letters scratched out with white chalk pop out against the background of dark stone. They spell out “E. Block”.

Whether they are new and shiny or old and battered (and likely punctured) depends on how much time has passed since a new batch of students came in

Housing students for three quarters of a century, E-Block has a hundred rooms and is the oldest hostel still standing. While the main entrance is duly closed at 11 pm every night, there is a back entrance which, as a consequence of recent developments (explained later), is kept open for 24 hours.

The two entrances stand as an allegory to the hostel’s dual nature. The students who reside within a hostel’s walls build friendships that last a lifetime and rivalries that last a bit longer. Some experiences leave imprints so deep that they evoke nostalgia even when too little time has passed to warrant such indulgence.

Meanwhile, the hostel building itself has stories to tell. Rebellious graffiti that now hides under many layers of paint, or a window with gratings which were never installed – a secret entrance for generations of students evading early curfews. Or the tale of how an extra floor was built in haste to accommodate an intake of students that provided much-needed breathing room – today, it leaks tendrils of water with every one of Bangalore’s erratic showers.

****

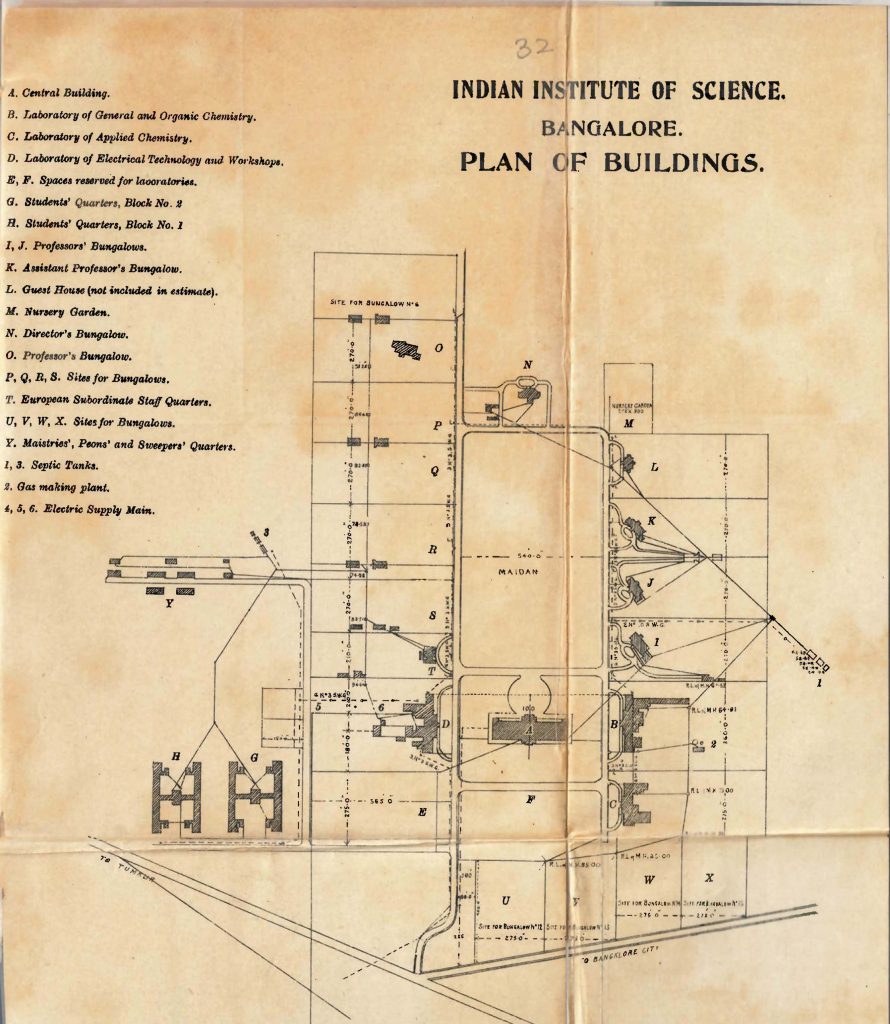

The story of IISc’s hostels begins with two quarters, built approximately where the New Girls Hostel (NGH) and New Boys Hostel (NBH) stand today. Each quarter contained 36 rooms arranged in two rows, with mess rooms at the ends of each row. These rows were built parallel to each other, with latrines and baths located in the space between. Two sets of rooms in each row would be connected to function as a seating room and a bedroom, reserved for four “demonstrators (instructors)” to reside. A total of 64 students and eight demonstrators could stay here. In 1911, the first batch of 21 students began their scientific endeavours at IISc, and the student quarters were occupied for the first time.

As time passed, the student body grew exponentially, but there was a gender disparity in the available facilities. Although male hostels kept expanding, it was only in 1942 that the first permanent women’s hostel was constructed. Before this, only temporary accommodation was provided to female students and the resulting issues, such as the arduous task of constantly changing rooms, were highlighted in a 1936 letter from three women students. It was addressed to the then director, CV Raman, and delivered to him through his wife, Lokasundari Ammal, who was the Warden of the Women’s Hostel. In the same letter, the students also suggested that the Institute make the availability of accommodation for lady students known to the public. This would encourage and attract parents who were looking to send their daughters to IISc to pursue research.

Around the time of India’s independence, the need arose for another men’s hostel. And so, a building with 46 rooms on the ground floor was constructed in 1947-48. While students occupied these rooms, the construction of a first floor was said to have been “progressing rapidly,” according to the 1947-48 Annual Report. This was none other than E-Block, now a two-storied building with a long corridor, and rooms on either side. “It looks like a ruler on a map” is a common description that its occupants use.

By the time the Institute completed its Golden Jubilee in 1959, it could house 368 male students in seven hostel blocks – named A through G – along with nine women students in a separate block. This expansion in housing capacity was funded by an interest-free government loan that the Institute received at the time. The numbers grew, and by 1981, the hostels could accommodate over 1,000 male students and 100 female students. In later years, special accommodation facilities for married scientists, postdocs, and visitors also came up.

The increasing influx of students over the years has brought in some rather unusual problems – an outflux of showerheads, for instance. In 2005, a letter from the Deputy Registrar to the Security Office lays out the tale of chromium-plated showerheads being mysteriously stolen from the Rohini hostel bathrooms, and brass float-valves from overhead tanks in the F, G, and H hostels. While the staff and workers were suspected in this particular case, as noted in the letter, students have also been known to partake in mischievous theft in recent years. An anonymous student source claimed that locks belonging to the Hostel Office were stolen from a hostel during the summer break in 2025, collected in a bag and placed, surreptitiously, on the roof of the Hostel Office (whose staff, apparently, are still unaware that the hiding place is right above their noses).

****

S-Block overlooks the slope of the bank road and is located opposite the Faculty Club. With a spread out, almost circular layout, it is nestled in a corner and practically hidden by a compound wall, which is not much shorter than the building itself.

The construction of S-Block began around 1995-96, and part of the funds – Rs 20 lakh – was provided by ISRO, mainly to support 15-20 ISRO-sponsored students. In response to the kind gesture, faculty member KP Rao, Convener of the ISRO-IISc Space Technology Cell, made a request to the then Director, G Padmanaban, that accommodation be provided to sponsored students prematurely, starting August 1995, even though the actual hostel wouldn’t be ready until 1998-99.

“Nowadays, UG students are provided hostels like NBH and A-Block in their third year, but we were not so lucky,” says Pabitra Sharma, a former undergraduate student at IISc, who lived in S-Block for over a year, starting March 2021.

The increasing influx of students over the years has brought in unusual problems, like the outflux of showerheads

Since he also stayed on campus for a part of the lockdown, Pabitra feels that it influenced his outlook on hostel life. A major part of his first two years overlapped with the pandemic, and his batch had a rather atypical experience of hostel life. As they were entering the third year, the restrictions began to fall away, and new hostel room allotments were on the horizon. Of course, there were strong opinions on the kind of rooms that they would prefer.

“We were looking forward to a housing facility where we could get some sunlight,” says Pabitra. “More than anything else, we wanted to see other people’s faces. Another thing was the desire for balconies, so we requested A, B Block or NBH.”

Those specific hostels boast a large number of students, comfortably sized rooms with a balcony, and more than anything else, a sense of community – something these students were pining for after being cooped up for so long. Their earnest requests, however, were denied, and Pabitra and his batchmates were relegated to S-Block, which had only two floors. Current students, on the other hand, are allotted those airy hostels by default, and are sometimes even allowed to decide which rooms they want. “I think it’s unfair!” laments Pabitra.

****

Over the years, the Hostel Office also had to adapt to the growing number of students. “I remember the old days when everything was manual. We had around 14 people working in the Hostel Office,” says BS Sheshachala, former superintendent of the hostels. “Today everything is computerised, so only 6-8 people are needed.”

Sheshachala worked at the Hostel Office for 40 years from 1979 to 2019. He has overseen many changes and transitions in hostel allocation and management. He feels that the older system of handling hostel bills and documents manually was better, because it encouraged camaraderie between students and the administration. Since everything was in writing, students had to visit the Hostel Office every month to pay their mess bills, and got to interact with the staff more frequently. Sheshachala recollects knowing most of the students on a first-name basis.

“Whenever I see an old student, they always ask me: ‘Where are you these days, sir? Still in the Hostel Office?’” says Sheshachala. “Once, I met an old student. I went over and asked him whether he was from the Physics department. He was confused and asked me how I knew. I then recounted his guitar-playing skills and the hostel he lived in, and he was totally shocked! He was very happy to speak to me.”

According to Sheshachala, another benefit was the possibility of ensuring compatibility between roommates. Students from the same place were often given accommodation together in case of shared rooms. This offered solace and familiarity in a new city surrounded by so many new faces. However, such considerations drastically reduced after 1995, when a lottery system was introduced to allocate rooms. New students picked out chits, and rooms and roommates were allotted randomly. Single rooms were always sought after, and seniority was the deciding factor to get them when they became available.

Agrim Arsh, a second-year BSc (Research) student, says that he was incredibly frustrated with the lot system and struggled for two days to get a room allocated. On the first day, he was allotted room E28, but it was a storage room and was full of luggage. He was told to come the next day at 11 am. “When I arrived, the luggage had been cleared out. However, E28 had now been declared a ‘Medical Room’ and couldn’t be allotted. I went back to the box of chits and picked out E5. On going there, I saw that the room was locked. I called my assigned roommate, his mother, and then his father. None of them picked up.”

Students from the same place were often given accommodation together … offering solace and familiarity in a new city

This is when Agrim took matters into his own hands. After roaming around for a while, he came across E100. “This is the most spacious room in the hostel, and can comfortably fit three people, even though only two actually live there. A senior was living there at the time, all alone. I basically demanded that I be allotted the room, after all the running around I had done. It worked, and that’s how I landed the biggest room in the hostel!”

****

“All the students who have moved to the New Hostel Complex are hereby requested to hand over the keys of their old rooms to the Hostel Office immediately.”

This notice from 2004 signalled the opening of the New Hostel Complex – including the new A and B Blocks with 900 new rooms, along with attached messes having the same names – as the new home for a majority of the student population. This was followed by the decommissioning of the A-H hostels, excluding E-Block. All of these had been constructed in the 1950s and had seen multiple generations of students pass through their halls.

While F and G Blocks were recommissioned in January 2005 due to a housing crisis, almost all the old buildings were eventually demolished and gave way to the New Boys Hostel (NBH) and the New Girls Hostel (NGH). E-Block, however, was refurbished for the use of UG students, the last remnant of the older generation of hostels.

“E-Block was special because I lived there during the lockdown. We were working on a project and had permission to stay on campus while following social distancing protocols,” says a former BSc (Research) student, who preferred to stay anonymous. “We were severely undersupervised and got into a lot of mischief during those days. E-Block, having two doors, is great for accessibility, but causes security issues. When we were living there, the back gate was locked. So, we broke the lock. In response, a bigger lock was installed by the authorities. This time, we unscrewed the hinge and managed to remove the lock. Our next challenge was the door being locked from the outside, so we removed the entire door! After that, a security guard was placed at the back gate, but no more locks were installed.”

Until a few weeks ago, the back door of the E-block building was still closed with loops of jute rope, and all traffic came through the front entrance. Late one night in July 2025, the rope was cut, and the back door was open once again, making it much easier to get to the messes and the Sarvam Complex.

But that wasn’t the end of it. A few days later, a rather sturdy lock showed up in place of the rope. While no one had the stroke of inspiration to remove the entire door, a neater solution was devised by an unknown group of E-Block residents. The very handles to which the lock was attached were removed, leaving the back entrance open for use.

Since then, the entry arrangements have seen a radical shift. E-Block now has its front door duly locked at 11 pm. The back door remains unlocked for 24 hours, albeit with a security guard present. Only we residents know that the reason is not because of a policy decision, but because its handles have been surgically extracted making it impossible to lock. Until the next time someone tries a different tactic to make our hostel life more interesting.

Aarav Ghate is a second year BSc (Research) student at IISc, and a science writing intern at the Office of Communications

(Edited by Ranjini Raghunath)