Gursaran Pran Talwar blazed trails in indigenous vaccine development

In October 1994, Gursaran Pran Talwar was in a fix. He had only a month to leave the National Institute of Immunology (NII), an organisation that he had built from the ground up, as his tenure was coming to an end. But his work on developing what might become the world’s first female contraceptive vaccine was just gathering steam.

A few months earlier, Talwar and colleagues had published a landmark study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showing how their vaccine prevented pregnancy in all but one of 148 women enrolled in a Phase II clinical trial. The vaccine triggered the production of antibodies against the human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) hormone, which is critical for embryo implantation. It was expected to be safe since hCG is produced naturally by the body, and no major side-effects were seen in earlier trials.

But their success was swiftly followed by criticism. Some scientists accused the team of rushing to carry out clinical trials without sufficient animal studies. Women’s groups questioned whether participants were fully informed about the potential risks of such an experimental strategy. Concerns were raised about whether the vaccine could cause infertility.

It wasn’t the first battle that Talwar had fought over a vaccine. Decades earlier, he had led the development of India’s first leprosy vaccine at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS). Not only had he competed against two other groups developing similar vaccines, but one of the competitors even claimed that the bacterial strain used for Talwar’s vaccine was identical to his.

“If someone works well, there is a reaction against them,” Talwar says, with a shrug. The 98 year-old had visited IISc in October this year to attend IMMUNOCON, an annual conference organised by the Indian Immunology Society. “I ignored unsubstantiated aspertions, all of it,” he continues. “If I am convinced that I am doing the right thing, and good science is practiced, why should I worry?”

From Lahore to Delhi

Born in Hissar (now part of Haryana) in October 1926 and growing up in Lahore, Talwar recounts having a difficult childhood. Although he was interested in medicine, at his father’s urging, he pursued a BSc (Honours) in chemistry and a Master’s in chemical engineering. He loved rowing – he would ride his bicycle every morning to rowing practice. “I became captain of the college team. We won all the trophies,” he recalls, smiling.

Partition forced him to flee to India – he finished his final year exams in a migrant camp in Delhi in 1948. Two years later, he secured a scholarship to pursue higher studies in Europe. “I chose France because I had a leftist inclination … liberté, égalité, fraternité,” he elaborates.

At the Institut Pasteur in Paris, he studied fermentation technology, assigned to a division that maintained yeast strains used to make champagnes. “The first time that I tasted champagne, I wondered why it was so special. It had no taste. I was not interested,” he recalls. He was then transferred to the biochemistry division, where he got to work with Nobel laureate Jacques Monod. After completing a DSc degree, he pursued a postdoc in Germany under a Humboldt fellowship.

In 1956, Talwar came across a pamphlet advertising the launch of the first AIIMS in Delhi, and applied for a faculty position. “I did not expect that I would get selected,” he says. “To my surprise, I was offered an associate professorship of biochemistry. I was the second faculty member to join.”

Talwar’s first few years at AIIMS flew by in overseeing whatever was required to raise the fledgling institute – from setting up laboratories to teaching biochemistry. “Biochemistry in most medical institutions was then a part of physiology. Its teaching was boring and minimal … My job was not only to introduce a contemporary, interesting, and exciting course in biochemistry for students … but also to educate my faculty colleagues on what modern biochemistry offered for their disciplines,” he writes in a 2005 perspective in the Journal of Biosciences. He was also enjoying his research on growth hormones.

Talwar’s first few years at AIIMS flew by in overseeing whatever was required to raise the fledgling institute

It wasn’t until 1970 that Talwar started thinking about vaccines. That year, an international WHO contingent visited AIIMS and urged Talwar to lead a Regional Training Centre, to tackle the growing burden of leprosy in India. Talwar was reluctant because he had no clue about the disease. The team then asked: With India having the highest number of leprosy cases in the world, shouldn’t Indian scientists, rather than Americans, work on this problem? Talwar agreed. “It took me in a different direction,” he says. “I had to work for a cause.”

Sparring with a scourge

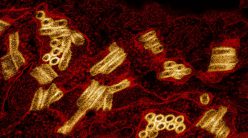

Leprosy is an ugly disease, Talwar points out. Caused by Mycobacterium leprae, it affects the nerves, throat, skin, and eyes of patients, leaving them disfigured and disabled. Talwar and colleagues focused on identifying what was happening in multibacillary patients – those who develop a large number of skin lesions. They found that immune cells called lymphocytes were not getting activated in response to M. leprae, which prevented the cells from identifying certain components of the bacterium and mounting an immune response.

Talwar then wondered if a vaccine could trigger this activation. M. leprae was not a useful vaccine candidate because it does not grow in a lab dish, and does not trigger an immune response in such patients anyway. His team, therefore, turned to a close relative – a harmless, fast-growing bacterium called Mycobacterium w. Its genome sequence was determined and thereafter it was renamed Mycobacterium indicus pranii (MIP).

Clinical trials – including a large-scale trial among four lakh patients and healthy household contacts in Uttar Pradesh under the National Leprosy Control Programme – showed that combining MIP with standard multi-drug therapy (MDT) cleared M. leprae much faster, cutting down treatment time by months. It also protected healthy family members of the patient from getting the disease.

The vaccine’s effects were found to persist for at least six years after the first dose. It became the first indigenous leprosy vaccine to get approval from both the Drugs Controller General of India and the US Food and Drug Administration. Cadila Pharmaceuticals bought the licence for MIP and started selling it under the name “Immuvac”.

The WHO declared India leprosy-free in 2005. “The stigma hasn’t reduced,” Talwar points out. “[Though] we’ve reduced the number of leprosy cases, the disease is not eradicated.”

Contraceptives and construction

Like leprosy, Talwar’s work on the contraceptive vaccine was spurred by a social problem.

In the early 1970s, he would travel frequently to Banaras Hindu University for their Governing Council meetings in Varanasi. On a walk around the city, he came across impoverished women looking “thin as rods” who shared their woes of having more children than they could afford to feed. “I asked them: ‘Family planning kyun nahi karte [why don’t you go for family planning]?’ They replied: ‘None of the options suits us.’”

Talwar realised that there was a need for a contraceptive that would not cause harmful side-effects like bleeding and delayed menstrual cycles. His team zeroed in on hCG, a glycoprotein that has two components called alpha and beta subunits. They took the beta subunit and fused it to the tetanus toxin to boost the production of antibodies. The first clinical trials showed that it could trigger anti-hCG antibodies in women. A follow-up study in four countries supported by the Population Council, an international nonprofit, confirmed that the vaccine was safe and effective.

In subsequent studies, the team linked beta hCG to the alpha subunit of ovine luteinising hormone (oLH), which produced higher titres of antibodies. In the 1994 study, out of 1,224 cycles tracked, only one pregnancy happened. The effects were reversible, Talwar says. If the women did not take a booster dose for about three months, they could conceive again and bear normal children.

Talwar realised that there was a need for a contraceptive that would not cause harmful side-effects

By this time, Talwar had also become keen on promoting immunology in India. As a Jawaharlal Nehru Fellow, he met with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, and made a case for the subject, pointing to how immunisations had lowered child mortality. “I remember having written the proposal for a ‘Centre for Immunology’ during a transatlantic flight, helped by lavish servings of champagne and caviar,” he writes in the perspective. The National Institute of Immunology (NII) was born out of this proposal, and inaugurated on 6 October 1986.

Talwar spent the next few years building the institute on a slice of land filled with “rocks and ravines” in the Jawaharlal Nehru University campus. “In less than three years, the main central building, auditorium, experimental animal house, primate facility, hostel for post-graduates, and 20 residences for faculty were built and made functional,” he writes. “This may well be the fastest pace at which a composite research institute has been built, nationally or internationally, without compromising on quality of facilities, or scientific potential.”

Talwar insisted that NII should be a residential campus. “There was no public transport available at that time, in that area,” he explains. He also wanted NII to become a “multidisciplinary institute” that would promote intense “inter-laboratory collaborations for taking a research lead to a potential product.” He was keen that the institute should attract talented Indian scientists working abroad. NII, thus, became a focal centre for immunology in the country.

“Dr Talwar has brought up an entire generation of Indian immunologists,” Soumya Swaminathan, former Director-General of ICMR and former Chief Scientist at WHO, once told the Indian Express. “Most directors at immunology institutes in India today were either taught by him or mentored by him. He is the father of Indian Immunology.”

Rising to challenges

At IMMUNOCON, former IISc Director G Padmanaban quipped to the audience that Talwar had been aptly named (“sword”) because he had been fighting all his life.

Talwar’s mother died when he was eight days old and life with his stepmother was not easy, he says. When partition split the country, he fled with the clothes on his back and took shelter in a friend’s house, before reuniting with his father in India.

“My work in leprosy and also on the beta hCG vaccine faced innumerable hurdles,” Talwar writes. A rival group at the Cancer Research Institute in Bombay accused him of using their bacterial strain for his vaccine. Talwar countered that MIP was unique. He and his colleagues also published a detailed genetic analysis, differentiating it from 30 other species of Mycobacteria.

‘My work in leprosy and also on the beta hCG vaccine faced innumerable hurdles’

As for the anti-hCG vaccine, the WHO declined to fund Talwar and backed a rival vaccine being developed by scientist Vernon Stevens at Ohio State University. The Department of Biotechnology in India also cut its funding for the vaccine, and downgraded it from a high-priority mission to a regular research project.

Debates about the ethics of such a vaccine also delayed its development. Contraception and conception were and continue to be sensitive issues linked to strong religious and cultural beliefs.

“Vaccine development is a long process. Procedures, procedures, procedures. Itni permission leni padti hai [so many approvals are needed],” Talwar rues. “You have to have not only the insight but also the capacity to see it through.”

When Talwar left NII, a friend identified a position at the nearby International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology where he could continue his research. By then, he had also secured a grant from the Rockefeller Institute in the USA to continue his work on the anti-hCG vaccine at his own research foundation in Delhi.

Talwar’s team recently started testing a combination of MIP and a new version of their anti-hCG vaccine, a genetically engineered recombinant containing the beta subunit of hCG linked to the heat-labile enterotoxin of E. coli (LTB), for contraception. Clinical trials, supported by ICMR, were stalled when some women developed nodules at the injection site. The team found a workaround – if the combination is given intramuscularly, no nodules were formed. He is now hopeful that the clinical trials will continue, once sufficient vaccine numbers can be manufactured for the trials.

Talwar just celebrated his 98th birthday on 2 October this year. “I [still] go to the lab every day, and my aim is timely completion of trials,” he says. His team is also working on immunotherapy for advanced-stage, difficult-to-treat cancers which express hCG ectopically (on the cell surface).

“I think the going is not bad,” Talwar adds, with a smile. “The mission of completion of trials and conveyance of benefits to users within my lifetime is what I strive for.”