The importance of introducing traditional knowledge to young scientists

Can complex scientific concepts and mathematical theorems have a dialogue with Indian folk dance?

This was the question I posed as the end-term assignment for the course on ‘Mapping India with Folk Art’ that I was offering to IISc’s undergraduate students in 2015. I asked the students to pick one ground-breaking research contribution in the past 100 years within the disciplines of physics, chemistry, mathematics, biology, earth science and environmental science, and depict it through any Indian folk dance form.

“As part of the mathematics group, we decided to portray the Four Colour theorem through Kalbelia, a Rajasthani folk dance,” recalls Angana De, former IISc UG student, now a PhD student at Purdue University. “The aim was to depict the incongruity that arises between the colours when the Four-Colour theorem is not satisfied, through erratic [dance] movements. The incongruity would turn into harmonious, graceful dance moves when the theorem was satisfied. We used to discuss and rehearse every night after dinner, for an hour or two, for two weeks. It was a truly unique experience to brainstorm, teach and dance with group members who had never danced before and to bring the Four-Colour theorem to life.”

On a Monday morning in 2013, Raghavendra Gadagkar, DST Year of Science Professor at the Centre for Ecological Sciences and the then Chair of the Centre for Contemporary Studies (CCS), asked me, “Would you like to design and teach a course to the undergrads?” CCS was entrusted with the responsibility of building the humanities curriculum of the newly commenced Bachelor of Science (Research) programme. I had just completed my PhD and the prospect of teaching was both exciting and daunting. And so, without any hesitation, I said yes. That was the beginning. This year, I just completed the 10th edition of this course.

Rarely are students encouraged to understand the country through the living, dynamic and multifarious art forms of the common people

Schools and colleges teach students to appreciate India through its history, geography and politics. But rarely do they encourage students to understand the country through the living, dynamic and multifarious art forms of the common people. When I was given this opportunity, I decided to draw on my MA (Cultural Studies) background to design a hands-on course that would be both relevant and engaging for science students. ‘Mapping India with the Folk Arts’ brings into the classroom the knowledge of the common people, acquired through their lived experiences.

Bringing paradigms together

The sciences – natural, social and applied – have emerged over the years as the most credible form of knowledge dissemination. In parallel, however, exists people’s knowledge or traditional knowledge that also captures other facets, such as living in harmony with nature, conservation, healing and agriculture. This knowledge is handed down from one generation to the next, with or without the help of written documents. Methods and practices described in science versus traditional knowledge are different. This is all the more reason why the two forms of knowledge need to become more cognisant of the other. In recent years, scientists have begun realising the importance of including the values of traditional knowledge, especially in medicine and ecological adaptation. There are potentially more areas where the soundness and ingenuity of traditional knowledge can enrich queries of science. Through the course, I wanted to get IISc’s science students to not only become familiar with the diversity of the country but to also appreciate the values and philosophy behind indigenous knowledge.

Folk art is unique, in the sense that the dexterity and creativity of the artists are not the focus, but the context of their production is. Events, materials and symbolism are important elements of folk art. This makes it an excellent resource for understanding the worldview of the community it belongs to. In the course, we treat folk art as windows to people’s way of life.

India is a vast and multicultural country. Art produced by its people is also varied and wide-ranging. Which is why, every year I chose a different folk art – visual, performative or narrative. By mapping the connotations and variations of this art across the country, the students are given an opportunity to comprehend traditions and customs unique to specific regions of India.

“The course allowed me to cultivate a profound appreciation for cultural expression. The vivid and dynamic colours intrinsic to Indian folk art traditions provide a tantalising glimpse into our nation’s vibrant and multifaceted heritage,” says Amrutha AD, a former UG student. She recalls how working on the group project at the end of the term – which allowed them to think of ways to bridge the gap between art and science – helped her dive deep into rich artistic legacies as well as form strong bonds with her teammates. She adds that it also helped them realise the importance of coming together as a group, emphasising the essence of folk art.

Exams with a twist

Assessments are compulsory for credit courses. I wanted the students to use this opportunity to try and bring different knowledge paradigms closer. Keeping their educational backgrounds in mind, I framed assignments that would help students blend their scientific aptitude with folk aesthetics.

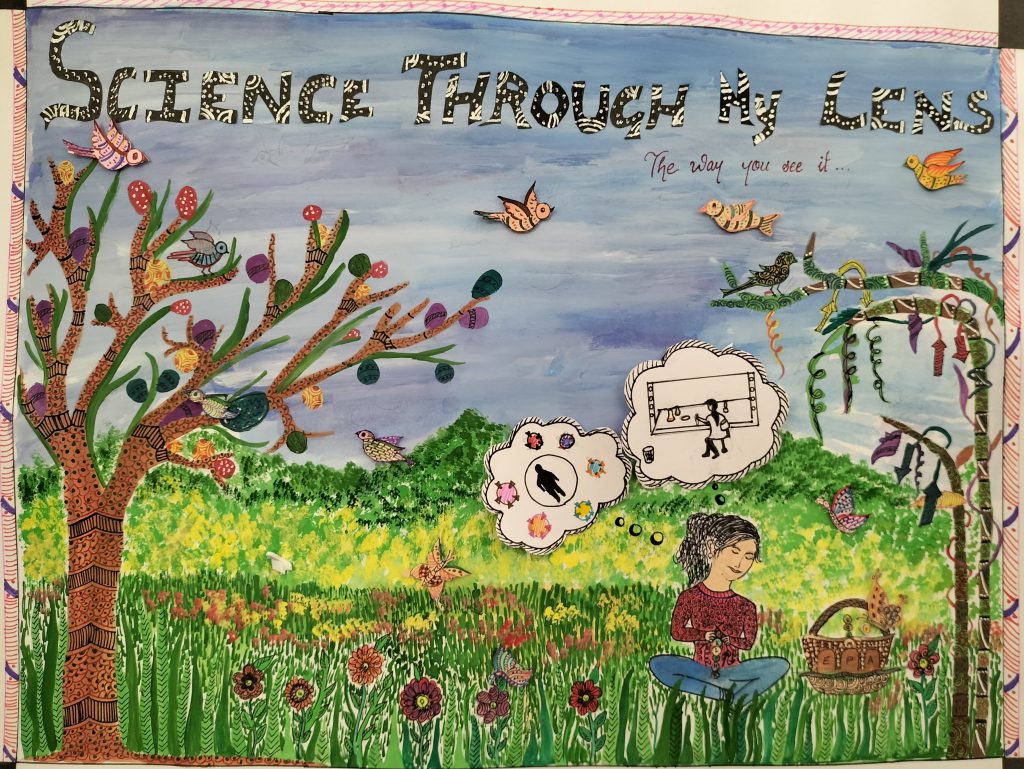

In one semester, for example, I asked them all to work on paintings depicting different scientific concepts using local art forms. All of them came up with exquisite original works that merged the spirit of science and folk art. For example, a Warli painting depicted a fun village scene where a man is thrown in a tub of water by his friends, and water is displaced due to his body’s weight, highlighting the Archimedes principle. Another group made a Gond painting showing the evolution of animals. Often folk art is mistakenly seen as unsophisticated and “rural”. However, the artworks that the students produced showed that the vocabulary of Indian folk art is rich enough to explain complex scientific and technological concepts.

The artworks the students produced showed that the vocabulary of Indian folk art is rich enough to explain complex scientific and technological concepts

Every year, when students turn in their assignments, I feel a sense of awe and fulfilment. As these are all original works at the interface of folk art and science, I have documented every one of them.

Many of the final assignments were public events. At the Folk Theatre Festival, students used, among others, art forms like shadow puppetry, Nautanki and Ras-Leela to illustrate Darwin’s theory, anthropocentrism, and gender disparity respectively. Sway with Science was a dance show where students depicted gravitational waves and the expansion of the universe, CRISPR-Cas9, and Haber process through Kolkali, Lavni, Dollu Kunitha – all regional dance forms – respectively. Another year featured That’s Another Story, where students showed how age-old folktales can have a different ending, given new knowledge and context. Sciencelore saw students composing original folk songs like Baul, Powada and Oggukatha to talk about how science has helped dispel superstitions. The visual assignments have been compiled into two books: Arting Science and Jal Jungle Zameen in the Age of Science and Technology. Other assignments included cooking curative traditional food, documenting oral histories, and researching folk costumes. One of the assignments given to the most recent batch was to collect folk songs from across India. More than a hundred folk songs have been collected that will soon be compiled into podcasts. The students collected these songs from their grandparents, neighbours and house help, among others.

Fostering critical thinking

“Being science students, such a course provides what we were deprived of in student life: A connection with Indian culture, in a curious and unique way through the folk arts of India,” explains Gaurav Sujit Kasliwal, a UG student at IISc, who completed the course in April 2023. “As most of us hail from urban areas, this provided a gateway to reminisce about our culture back home and gave us a new topic to talk over with our pan-Indian classmates, introducing us to new aspects of their culture. The most memorable part of the course was the assignments, which compelled us to research, create, and indulge in performing folk songs. It made us aware of the multiple identities that constitute Indian nationalism.”

Amrit Mahendra Joseph, another UG student from this year’s batch, explains how he also found the group project “refreshing”. “It allowed us to divide our work into aspects that interested each of us – be it writing lyrics, finding music to match the lyrics, playing an instrument alongside a performance or even acting out a performance with the songs in the middle of it.”

What has been especially gratifying for me is the popularity of such a course both within and beyond the Institute. I have been asked to give similar courses for the new MSc in Life Sciences programme and the BTech in Mathematics and Computing programme, as well as the Teachers’ Training programme at IISc’s Challakere campus. I have also been invited to deliver talks and conduct workshops in places like IIT Ropar and IISER Mohali. What started as an experiment in IISc’s UG classroom has now spread far and wide.

Siddharth Kankaria, who was among the first batch of students that took this course, is today a science communication researcher and practitioner at the National Centre for Biological Sciences. Reminiscing on its usefulness, he says, “I found the course to be a welcome break from the natural sciences courses in the UG programme. It was a very well-timed introduction to various folk-art traditions practised across the country, at a stage when we were still building our foundations in science.” Siddharth points to how current science pedagogy and curricula prioritise science as the only “legitimate way of making sense of the world.” “In that context, the course did a fantastic job of exposing us to other ways of ‘doing, seeing and knowing’. It also enabled me to eventually acknowledge that there is a plurality of knowledge systems, expertise and lived experiences that merit space and attention, especially when we are trying to solve complex problems like climate change, pandemics and pollution. But these were benefits that I was only able to appreciate in hindsight, long after I had graduated, and speaks to why it is so critical to include such humanities courses within science curricula across the country.”

Humanities, at its core, instils critical thinking. There have been many occasions in the 10 years where students have creatively elucidated humanistic sensibility. Once, they used Chhau art form to critique the displacement of tribals in Niyamgiri hills, Odisha. In another semester, they used folk theatre to highlight the impropriety of the god Krishna stealing the gopika’s garments in mythology. Such performances showed me that students are able to use folk art to not just show, but also discuss and debate. This is something that I will continue to cherish for a long time.