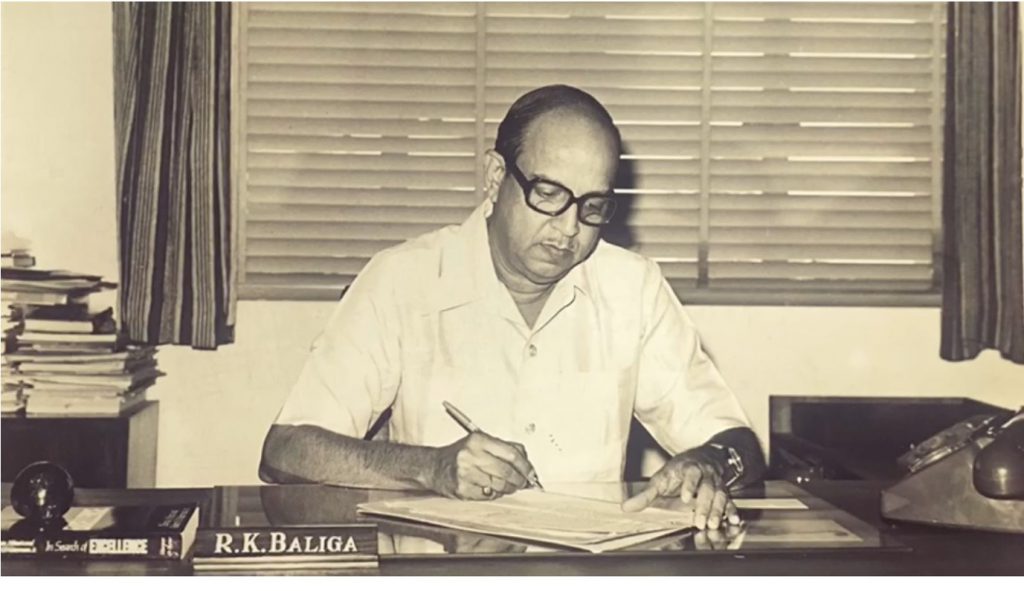

The story of Rama Krishna Baliga, a government bureaucrat who laid the foundation for Electronic City, which eventually led to Bangalore becoming the “Silicon Valley of India”

Ragavendra R Baliga has fond memories of his father, Rama Krishna Baliga. “There’s an article my father wrote for my medical school journal after he retired. [In that], he said, ‘I envision the belt from Bangalore city to Hosur to be bubbling with activity.’”

Rama Krishna Baliga (RK Baliga) was born in Mangalore on 29 December 1929. His father, Bantwal Vaikunta Baliga, was a lawyer, social activist, and freedom fighter, who also served as a speaker of the legislature for the State of Mysore.

After completing a Bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering from Annamalai University in 1951, RK Baliga came to IISc for his Master’s in Power Engineering (this degree was called DIISc back then). Baliga was also active in extracurriculars. While at IISc, he was the treasurer of the Gymkhana for one year. After completing his Master’s, he worked as a research assistant for six months.

In 1953, on the recommendation of the then Director of IISc, MS Thacker, Baliga was invited by General Electric (GE) to work with them for a year. Therefore, when he was 24 years old, Baliga sailed to the USA from Bombay via London on the ship Mooltan. “The Institute was key, because that is where he got the leverage to go to the USA, get exposure and come back,” says Ragavendra.

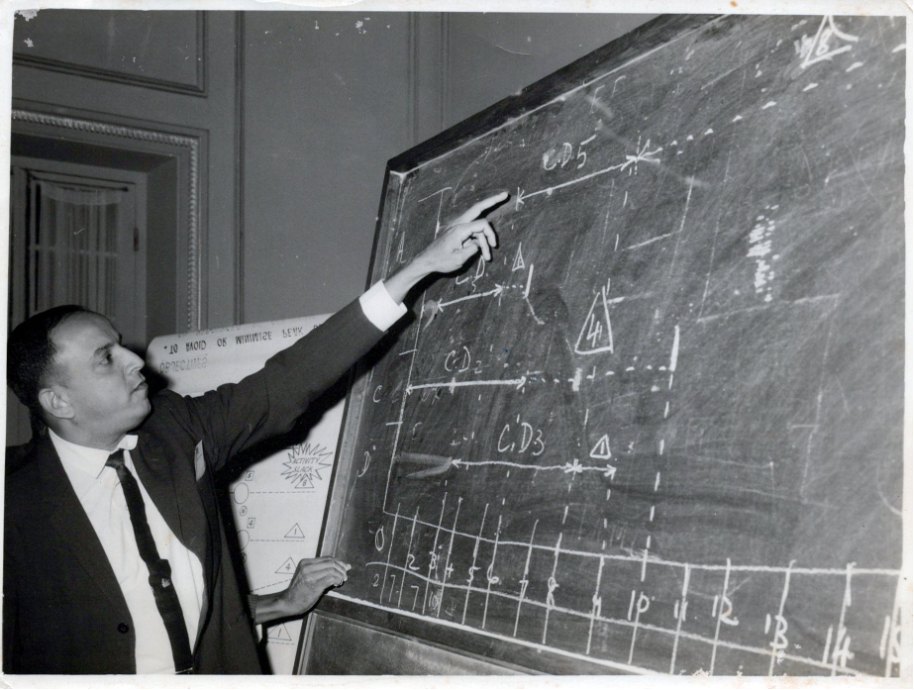

During his tenure at GE, Baliga worked at their different offices across the USA – in Erie, Pennsylvania; DeKalb Illinois, and Schenectady, New York. While working in DeKalb, Baliga wrote an article for General Electric News titled My homeland – India, highlighting the rich heritage and culture of his home country. He also did an evening course in economics and advanced engineering. “He was a consummate learner,” recalls his son. The nature of his work at GE ranged from control development engineering to production, testing and quality control of motors, turbines, and generators.

After one year at GE, in 1955, Baliga moved to Westinghouse Electric Corporation, the US company that built the fastest elevators for New York’s Rockefeller Center, and also designed the now famous “We can do it!” poster, which originally hung in Westinghouse factories to encourage women to take up wartime jobs. There, he worked on switchgears, large generators, motors, and air conditioning units, while also gaining sales experience. Years later, in 1969, Westinghouse International profiled Baliga for their Graduate Student Communicator magazine, where he said, “The role of the young Indian engineer of today is, of course, predicated upon the technological advances that have been made in the last decade. Such a man must be completely up-to-date in his field.”

In early 1956, Baliga moved to Oakland, California, to work in Kaiser Engineers Overseas Corporation for two months. He then sailed back to India after being assigned as a project engineer to MS Tata Iron and Steel Company, Jamshedpur. Three years later, Baliga worked at a subsidiary of Union Carbide called National Carbon Company Limited in Kolkata for about a year. On 10 May 1959, he married Chitra Pai, now Shanthi Baliga, an educator and social worker. They eventually had three children – Ragavendra, Narendra and Lathika.

(Photo courtesy: Ragavendra Baliga)

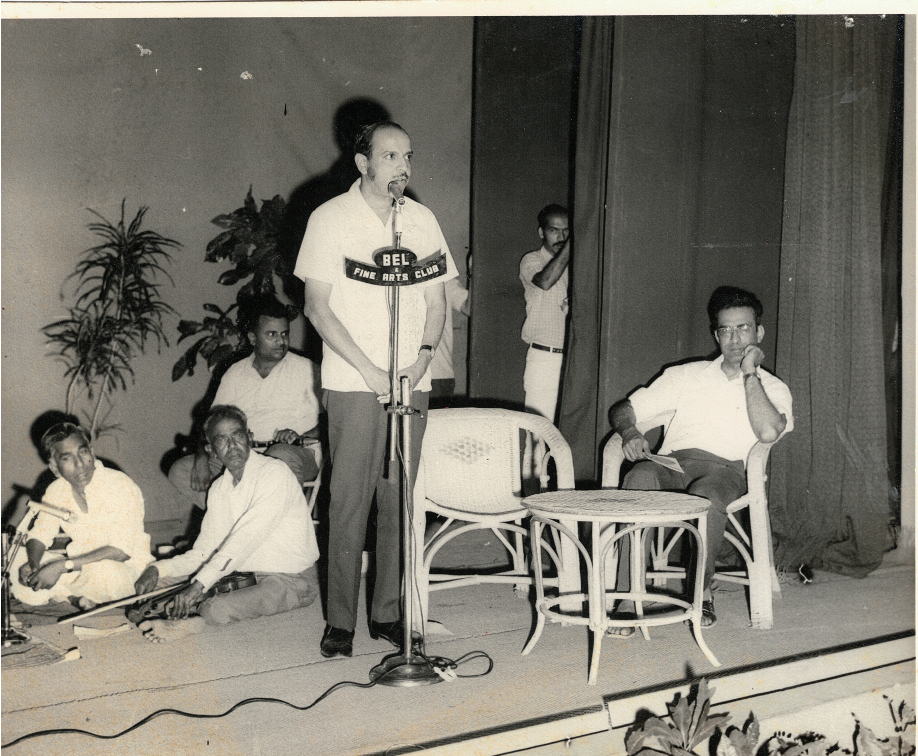

Baliga returned to Karnataka in 1960, and started teaching engineering to students at Manipal Institute of Technology, where he also set up the Department of Electrical Engineering. In the same year, Baliga went to Paris for six months to get a certificate course in Management and Production. Following this, he worked at Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL) for 15 years. As chief engineer, he was responsible for developing the residential colony of the company consisting of more than 1,400 houses. Later, as President of BEL’s co-operative housing society, he developed another colony of 1,500 houses. In 1972, Baliga was sent by BEL to Nippon Electric in Japan, for three months.

Work-life balance

Baliga was not a workaholic, Ragavendra says. As President of BEL Fine Arts Club, he organised drama and music festivals in ten different languages, which encouraged industry workers and their families to showcase their respective cultures. Baliga’s family would take walks outside the BEL campus. Whenever they passed by IISc, which was close by, his father would say to Ragavendra: “This is where I went to school.”

Venkatraman Balasubramanian, a friend of Baliga’s son, Narendra, recalls that RK Baliga was “soft spoken and gentle, but also energetic and mentally strong.” He fondly remembers that Baliga wrote a character certificate for him that he still has in his possession. Whenever Venkatraman went to meet Narendra and ran into his father, they would chat about the latter’s travels and learnings. “I enjoyed his company whenever I met him,” remembers Venkatraman. “Some of the conversations were all about his adventures, his enthusiasm, and his vision to start something.”

Baliga had one rule: The entire family had to have at least one meal together

When Baliga turned 45, he built his own house at Palace Cross Road. “Two houses down was Satish Dhawan’s house and one house down was S Ramaseshan’s house – both ex-directors of IISc,” Ragavendra recalls. At home, Baliga encouraged his children to be whatever they wanted. “There was no pressure to be like him,” Ragavendra says. Baliga had only one rule: The entire family had to have at least one meal – preferably dinner – together. Dinner table conversations centred on ideas to make a better society. “I think this is true of all the people of his generation. They were not [concerned only] about personal profit, or becoming billionaires. It was also about [contributing to] society … about the greater good.”

In the evenings, Baliga taught MBA students at Bangalore University. He was also a guest faculty member at the National Productivity Council. He joined the Rotary Club in Bangalore, where GVK Rao, the chief secretary of Karnataka was also a member. “He had direct access to [GVK Rao] at that time,” says Ragavendra.

Building a city

Baliga also became the President of the Institution of Plant Engineers, Karnataka Chapter, in 1976, and organised its fourth national convention, called Plantex-76. He invited officials like GVK Rao, TA Pai (Minister of Industry and Civil Supplies), and SM Patil (Chairman of Hindustan Machine Tools) to the event.

Six months after this convention, the Government of Karnataka established

the Karnataka State Electronics Development Corporation or KEONICS as a public enterprise with the aim of turning Karnataka into an ‘electronics state’. It was set up in Bangalore with a capital of Rs 1 crore, and Baliga was appointed its Chairman and Managing Director. KEONICS assisted small and medium-scale industries, both public and private, to develop technology and products related to consumer electronics, radar, aerospace, defence, medical electronics, computers, and industrial electronics.

Their pamphlet from back in 1976 mentions the numerous activities taken up by the corporation, which included providing vital resources like raw materials, testing and development centres, and finding markets for products both at “home and abroad”. The corporation also designed and manufactured the air traffic control desk for the HAL airport, as well as instruments like the iontophoretic-cum-neuro-exciter used by dentists, and dialling units for teleprinters.

The 1970s were a time of rapid developments. Electronics was a burgeoning field, with the television having been introduced just a few years earlier. India was independent, and there was a huge push to manufacture electrical and electronics equipment, for economic growth and for the sake of self-sufficiency. Computers were in their nascent stages and the IT revolution was yet to come.

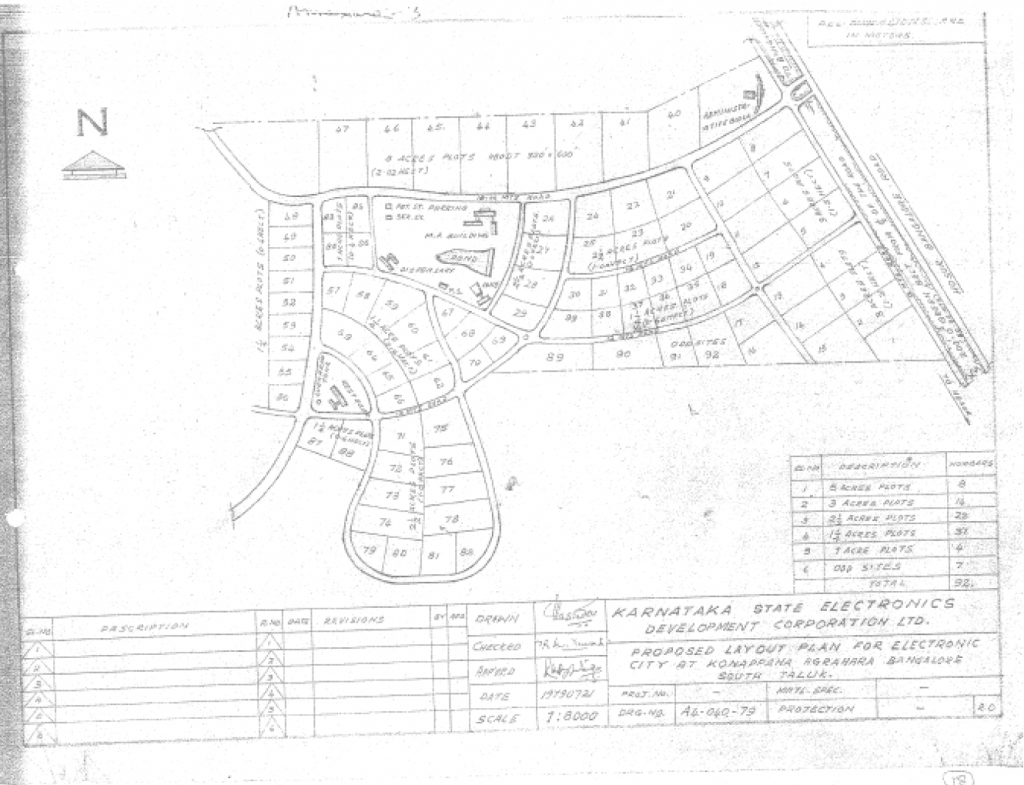

In 1979, at the 13th meeting of the KEONICS Board of Directors, RK Baliga put forth an ambitious proposal for setting up Electronic City. The project laid out every detail related to development and implementation, including financial resources, water supply, transport and housing. It was approved by the Board, and the then Chief Minister, Devraj Urs, signed off on 300 acres of land in Konappana Agrahara village, 20 km south of Bangalore city, on the way to Hosur.

It is not exactly clear when or for how long Baliga had the idea for Electronic City. Ragavendra suggests that because of his experiences, and his travels to the USA, France, and Japan, his father was able to envision an entrepreneurial city. A Vijay Times Connect newspaper article from 2 November 2006 concurs, stating that “his idea for Karnataka as an electronic hub was developed during his visits to France and Japan.” Indranil Ghosh, author of the book Powering Prosperity, wrote that RK Baliga “dreamed of making Bangalore into the Silicon Valley of India – an ambition that was met with derision in India as well as in the US. But he was not deterred.” Ghosh continued that it is hard to exaggerate how big an achievement this was for Baliga – one that owed a lot to the foresight of the then Chief Minister as well. India was deeply bureaucratic in the 1970s, making business creation extremely difficult.

With the green signal to move forward, KEONICS charged ahead to build Electronic City. A 1981 KEONICS Annual Report mentions that the response for the company’s advertisement for allotting sites had been encouraging, and several large electronic industries had shown interest. In an article in a 1983 issue of Sunday magazine, RK Baliga said to journalist Tirthankar Ghosh: “Our aim is to create around 10,000 jobs in the electronic industry in the state. You see, we do not have an industrial culture like Japan or the USA. Whatever strides we have made are from 1956 onwards, when India started industrialisation.” In the article, speaking of the future, Baliga said that he had a dream of establishing mini electronics cities in other parts of Karnataka as well.

In 1984, Baliga left KEONICS and served as the Chairman of Hindustan Teleprinters Limited for three years. He introduced electronic teleprinters for the first time in the country, in place of the outdated electro-mechanical teleprinters. He continued to engage with other organisations like the Rotary Club and the All India Public Sector Sports Association. On 26 October 1988, he passed away at the age of 58 due to diabetes-related complications. “Even though he had left BEL 12 years before, three busloads of people from BEL came for his funeral,” recalls Ragavendra.

In 1991, India went through an economic crisis mainly caused by over-dependence on imports. In response to this, the new prime minister P Narasimha Rao and finance minister Manmohan Singh laid out economic reforms that ushered in a new era of liberalisation for India. These reforms boosted the growth of Electronic City further which, by then, had almost 90 companies. This was also the time when the software sector was starting to take off. Dinsha Mistree, a lecturer at Stanford Law School wrote a paper in 2018, where he talks about the ease with which a foreign software company could register itself with the state government of Karnataka – within an afternoon, instead of the usual time of several months.

Today, not only does Electronic City house about 158 industrial technology companies, it has also transformed into an IT hub with over 200 companies like Wipro, Infosys, Hewlett Packard and more. The area alone provides jobs to over three lakh people. The Bangalore-Hosur highway buzzes with activity, just like how Baliga had envisioned.

Ragavendra hopes that his father’s story serves as an example of how someone with vision and conviction can make a major contribution to society. “He would tell us: ‘Try to help a lot of people, but don’t expect anything in return.’”