Harini Nagendra is a Professor of Ecological Sciences at Azim Premji University, Bangalore. She also leads the university’s Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability. Over the past 25 years, Harini has been studying the impact of urbanisation on both the ecology of a city and its people. For her interdisciplinary research, she has received many awards.

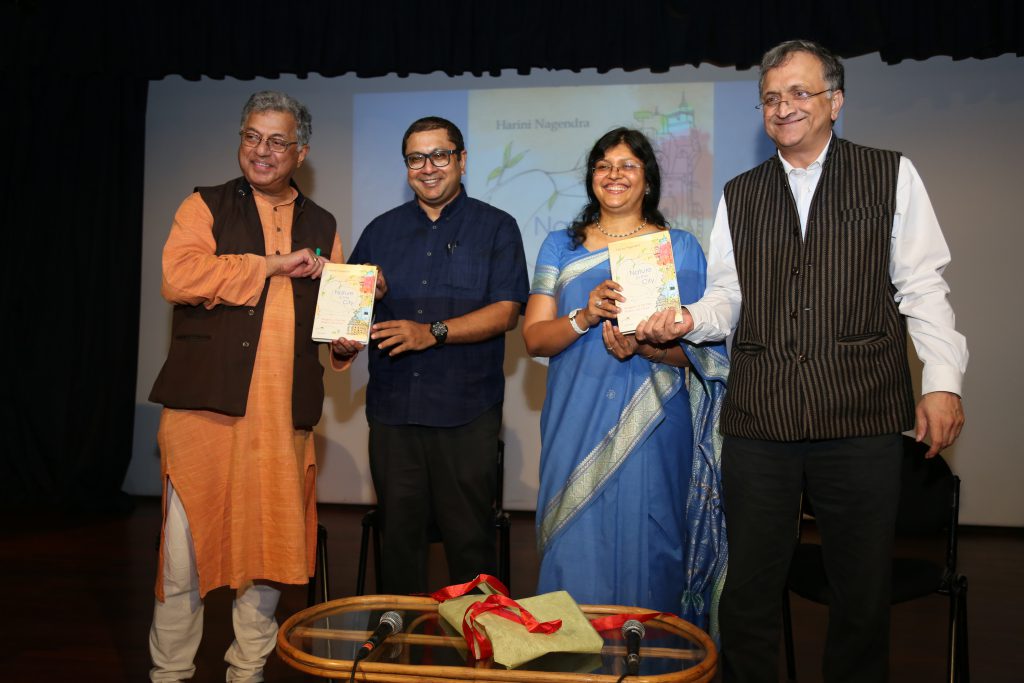

Harini has written several books based on her academic research, including Trees and Canopies and Nature in the City. In recent years, she has also ventured into the world of fiction and written two critically acclaimed books that are part of her crime series: The Bangalore Detectives Club and Murder under a Red Moon. She was recently in IISc, her alma mater, where she gave a talk about her research. CONNECT caught up with her for an interview in which she discussed her passion for urban ecology and writing.

What got you interested in ecology?

In retrospect, I think it happened serendipitously. I did a BSc from St Joseph’s College in Bangalore. I majored in Microbiology, Chemistry and Zoology. I then applied to IISc. When I got into IISc, I joined the integrated PhD programme in 1992 with the idea that I would do microbiology or molecular biology.

In the third semester, I did a lab project cloning a gene and purifying a protein. I absolutely hated it. It was just not for me. I would go in at 5.30 or 6 in the morning, leave at 12 at night, and things wouldn’t work. I was also worried about using these restriction enzymes – they were expensive, paid for with taxpayer money and I would get zero results; I suddenly realised that I’d spent thousands of rupees on something over the past week. That was a lot of money in 1992. And then, I just felt terrible. I was dissatisfied and was thinking of quitting.

At that time, the Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES) had its 10th anniversary, and there was an interesting talk on evolutionary biology. I went to listen to that talk, but by accident, I ended up hearing Prof Madhav Gadgil’s talk. He was talking about the same things that I was thinking of – that India should tackle problems relevant to the Indian context. We should do low-cost research. It was very inspiring. I got to speak to him and ended up doing my first project in CES.

What I’ve realised now in hindsight is because I was always a city child, I went with my parents for lots of walks in parks. I had an interest in trees, which is ironic because I took zoology, not botany, as I couldn’t draw all those diagrams in botanical records. As soon as I started ecology, I realised: “This is it. This is my thing.” It was complete serendipity and good fortune that I attended Madhav’s talk when I did.

Why did you switch to urban ecology?

After years and years of working in the Western Ghats, Nepal, West Bengal, Central India and other places, I realised that doing work in which I could apply the policy was impossible. I was always partnering with an NGO or an organisation that worked in that local area. I was very particular that we don’t do parachuting research, where you come in, you publish, and you go. That was never the aim. The aim was to contribute to something local, but the fact that you are not there, you can’t follow up, and given the realities of the Indian Forest Department or the ways in which conservation happens on the ground means that often science is not really taken into account. There is a lot of gap between the two [science and policy], in India and many countries across the world. That was beginning to bother me.

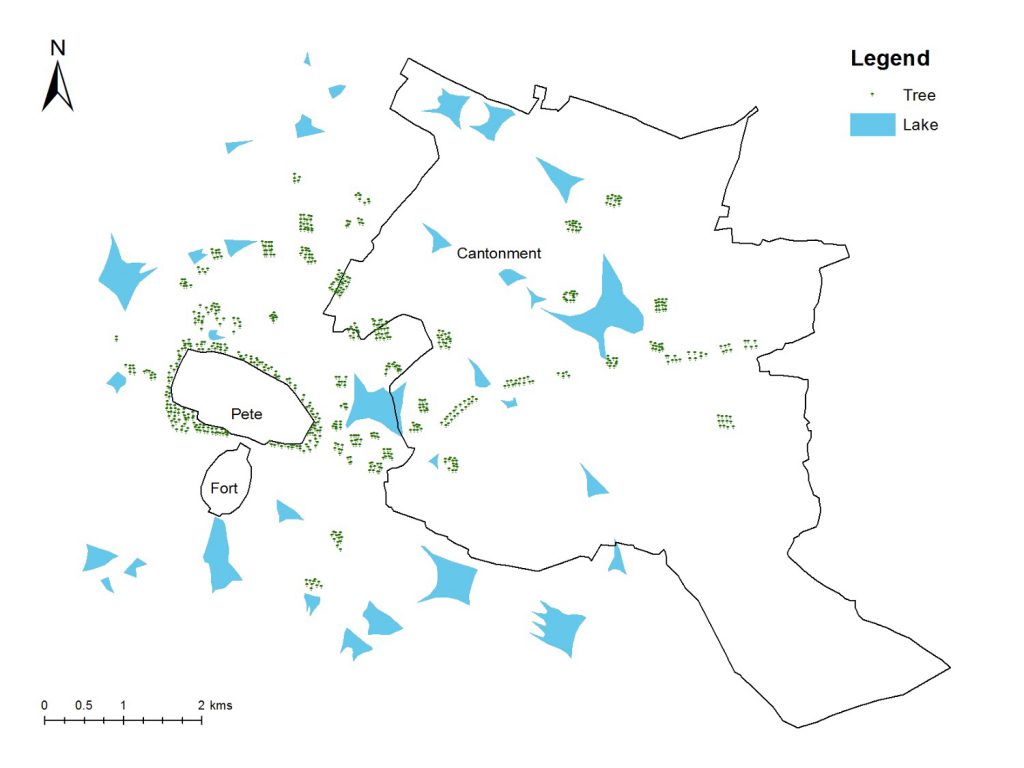

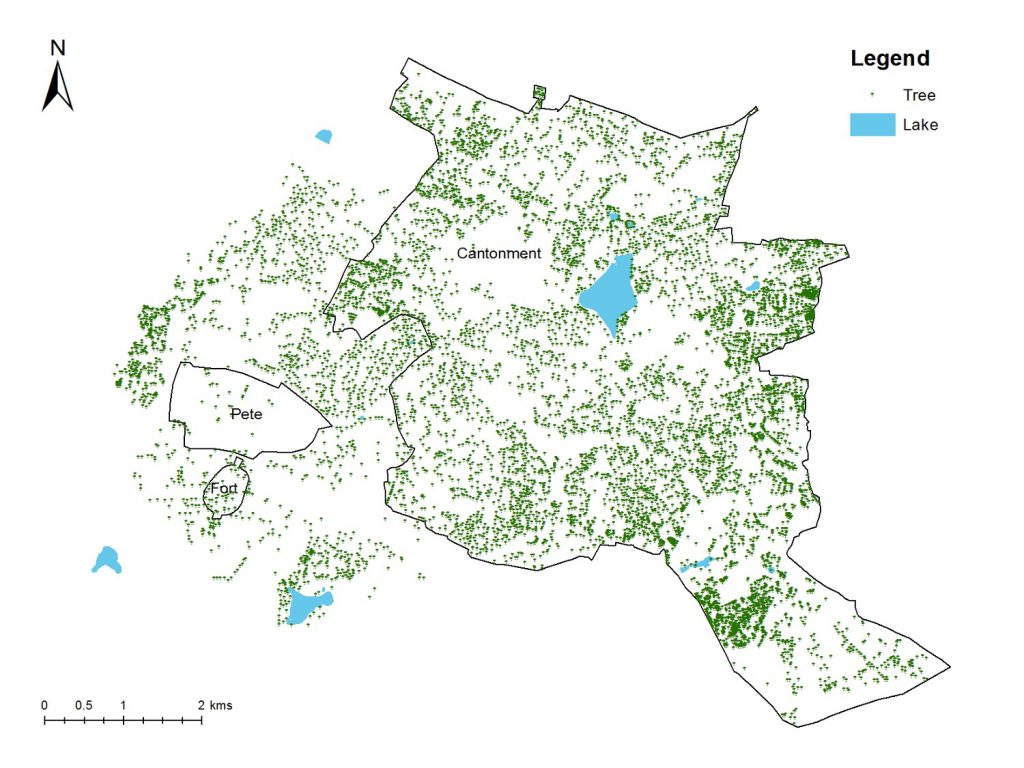

When I came back after my postdoc at Indiana University, I started urban ecology to help activism – by doing very simple things. We had BSc students volunteering with me. I would say, “Let’s go count trees and see whether government estimates of trees to be cut on the road are the same as our estimates.” We used to find that our estimates were often double [the government’s numbers]. We would then put out a citizen’s report saying that this is the environmental impact of tree felling on this road or that lake destruction.

Then I started working on a lake rejuvenation project near my house, not as a scientist, but adding that scientific part to the community aspect on lakes, their interconnectivity and hydrology. How should you restore this lake? Why should you not concretise it? Why should you not have lights, parking, and a food court in the middle of a lake? Why is ecology essential? Slowly, I realised that it had far more impact than my scholarly, more in-depth forest work. I also realised that there’s a huge need [for science in urban issues]. I find that a lot of younger people want to know what is going on in their cities. They want this information, and they want people to work with them and give them an idea of how to do scientific studies of these things.

Has your time at IISc influenced your work in any way? If so, how?

My time at IISc was my earliest introduction to ecology. In many ways, the early discussions with Prof Gadgil on this strong idea that we should do locally relevant, low-cost science, and use our brain to come up with ideas are things that have influenced me from the beginning. I was also at IISc when the Indian Academy of Sciences started Resonance, a journal of science education, and I was one of its early writers. I think my interest in science communication and engagement with societal problems came from that environment. The other thing is because of the integrated PhD, I could switch [subjects]. How many people have the fortune of saying, okay, I’m in microbiology, but I want to do molecular biology? The challenge was I knew nothing about ecology when I came in because my course work had no statistics, no ecological principles, no remote sensing software, no GIS.

So, I taught myself everything: coding, statistics, landscape ecology, remote sensing, GIS; I taught myself coding because we didn’t have money for software. Self-learning has its limitations, but it also gave me a sense of awareness that I can move into other areas which is, to me, a tribute to IISc’s open approach. That’s how I took up social science and then, history. Because it never occurred to me [then] that if I don’t have the training, I can’t do something.

Through your research, you have studied Bangalore’s ecological history very closely. Using it as an example, could you explain why the ecology of a place should be a crucial consideration when we develop a city?

People tend to think that in cities, ecology is not the primary concern; development is the primary concern. When they say development, they mean economic growth, and for that, they think you need flyovers, tall buildings, underpasses, and a metro. Of course, you do need them to some extent, but you can’t live in a city without clean air, good water, and wellbeing. Why do we need economic growth in cities? It is for wellbeing. But if we don’t put wellbeing first, we tend to put economic growth and say, “Never mind if wellbeing is sliding down, we have economic growth” – that is a very lopsided thing.

For example, we have shown that pollution – including suspended particulate matter and harmful gases like sulphur dioxide and nitrous oxides – is hugely reduced just by having trees on the roadside. The surface temperature of the tar road is reduced by about 20-25°C and the ambient air temperature is reduced by about 3-5°C just by having trees. That’s huge in terms of its impact on urban heat islands. It has spillover effects whereby if you have trees, you don’t need air conditioners; you can travel in a bus, you can cycle, you can walk.

Ecology in Indian cities also provides community social goods – acting as a place of recreation that also encourages people to come together. Migrants say that they bond with the city after being at a restored lake. They say, “I saw a bird or a tree or a flower that reminds me of my village.” It could be migrants of all kinds – from migrant labourers to people working in the IT sector, grandparents or elderly people coming to live with their children, and retired people. We were talking to some transgender communities, and they said, “If we stand anywhere, the police keep chasing us, saying you’re loitering. But at the lake, we can sit and look at the water. The lake doesn’t judge us.”

“If we stand anywhere, the police keep chasing us. But at the lake, we can sit and look at the water. The lake doesn’t judge us”

In a city like Bangalore where there is either flooding or drought, the lakes and the wetlands are very important because they are the sponges that hold on to flood water in the rainy season and give it back during the dry season. There are many things that we need nature for, and I think we forget all of this. You cannot import it. I can’t think of any way you can have wellbeing in the city without nature.

How can people go about getting educated about their city and giving back to it?

I think we need much broader public education of various kinds: from schools to educating the public, to working with the government because they are the biggest actors at scale – you can’t do any public action or education without the government. It is also important to educate corporates because they tend to be very narrowly target-focused – they want to plant trees. But education is more critical than simplistic targets such as planting 10,000 trees. For instance, many companies want to fund sewage treatment plants (STP) to revive a lake. Maybe you don’t need that. Maybe what you need is to use this money to restore the wetland upstream of the lake, and that will actually be more sustainable. Because the company may only fund this project for a year; it isn’t sustainable – to maintain an STP requires electricity. In contrast, a wetland functions on its own.

Another intervention suggested by my economist colleagues, including Amit Basole and others at Azim Premji University, besides me, was that, just like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), we should have a National Urban Employment Guarantee Scheme. Through this, you could fund a history, sociology or science graduate in every ward in Bangalore, for instance, and embed them in the ward committee to work alongside the corporator. Their job would be to go and document the lives of people in their place, their histories or microhistories, the nature of communities, and their traditions of engaging with nature. They would also document the temperature across the ward and generate a heat map, find out the waste dumping spots, document the local environment and identify troublesome spots, and put it up on a portal. They get jobs, they get training; the public gets information, and it can be a win-win situation. It is a work in progress.

We’ve been pushing it for a while. Some state governments seem to be interested, but it’s a long haul to get something like this actually implemented. In Bangalore, it’s very sad that we are an IT city, and we have no good data, not even something as simple as a tree count.

It’s very sad that we are an IT city, and we have no good data, not even something as simple as a tree count

What are some of the biggest challenges you face in urban ecology?

Schools and colleges have been very responsive to our outreach and public education efforts, but to reach out at scale, it is challenging. If you want to work with all the colleges and schools across Bangalore, you need some support from the government. Some departments of the BBMP [Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike] were excellent, like the Lakes Department. We worked closely for many years with a really good officer called Mr BV Satish, who was their chief engineer. We managed to get several lakes restored based on good ecological principles. Yet, sometimes it’s almost impossible to work with the government on the problem of saving trees because of infrastructure projects. You are often caught in the “Are you anti-development?” talk.

What we ecologists or any experts across the board would like is for the government to involve the public and experts before they start planning the metro lines or before they start thinking of the next five-year plan of growth. That kind of systematic engagement with BBMP doesn’t exist – it happens only occasionally, in fits and bursts. As a larger initiative across the city, such engagement also should not be only with one group of ecologists. It should be with the entire community – there are so many groups working in Bangalore.

The other challenge has been to get corporates and industries to engage with ecological restoration in a very systematic way. One or two companies will be keen to intervene sustainably, keeping ecological principles in mind. But most want something done very visibly and quickly. They’re not really thinking of the long-term impact. How do you work with them as a group across the city? Where I come back to in every example, is the scale issue. You can work in pockets in the city and those pockets have been very successful. Things are going well in some spots, but how do you actually scale this up across many cities – including Bangalore, Coimbatore, Bombay, Delhi and other locations?

What would you say to a student who wants to pursue urban ecology?

I would say there’s no better time than this to work on urban ecology. I’ve been going to the Student Conference on Conservation Science in Bangalore [a major conference held annually in six cities across the world] for over 20 years. Initially, students would come up to me and say, “I want to do urban ecology, but everybody laughs at me and I’m so excited that you are actually here in this conference talking about urban ecology,” or “My professor discouraged me; my fellow students are telling me that this is not worth doing.” Now you see at least 30% of the presentations have something to do with urban ecology – it could be about foxes, eagles, vultures, or ants. Yet, there is still not enough emphasis on social sciences related to urban ecology, which I think is a gap.

I feel like jobs are also opening up in the sector now because several corporate groups have an officer working on sustainability. They realise that sustainability is not just turning off the lights, but a lot of it has to do with the ecological processes around them. I meet many sustainability officers when I go to give talks in companies and many of them are environmental science or ecology graduates, which is very nice. I would say for anyone wanting to do this, this is a really good time to do urban ecology in India because opportunities are opening up like never before.

You are now also a well-known novelist. What prompted you to take up writing fiction?

When I was a child, I used to write a lot. In Delhi, where I lived then, there was a Shankar’s international children’s competition for art and writing – I won a couple of medals. I also had a small article published in Femina – for a children’s competition to write plays. When I was at IISc, I wrote scientific articles for Resonance, but alongside I also wrote children’s stories which got published in The Hindu and Deccan Herald.

Even when I was in Indiana University, I took a writing class, and wrote a couple of short stories – one got published in an online literary magazine. But somewhere along the way, I stopped writing fiction and science writing took over. My last fiction piece was probably written in 2001. Sometime in 2007, the idea of writing what later became The Bangalore Detectives Club came into my head. I’d never written a full book; I’d written lots of short stories but writing a full book and that too a detective fiction novel took a while. It took me about 12-13 years to complete the book – not that I was continuously writing. At some point I just took the plunge and said, “Let me finish this.” For me, writing fiction is a return to a first love.

Why did you choose to write a detective series? And how has your research shaped your fiction writing?

I was reading so many archival documents about old Bangalore and came across a lot of rich material which was not directly related to ecology – I wanted to integrate this into a story. Detective fiction, for me, was a natural way to do this, but also an important and useful handle because it’s something a lot of people read. You can use mysteries to discuss important issues in a non-preachy, non-judgmental way. I can talk about issues like equity and justice, or discuss what a good life in an Indian city looks like, and speak about communities and collectives. A big part of my work is to showcase how collective power leads to ecological protection. In The Bangalore Detectives Club, a group of women – and men – gets together and solves mysteries, along the way addressing societal problems and women’s problems. Writing the book really let me explore all of these ideas of justice, collectives, and other issues of urban life together.

I have so much research to draw on – including maps of the city and old newspaper accounts. For instance, from the Proceedings of the Mysore Representative Assembly in the 1920s, I got to know about the issues they were discussing, like the budget spent on lakes. I also came across documents with interesting historical details – for example, one detail I had put in the first book was that a tigress in Lalbagh once had cubs and she was not suckling them. So, the zookeepers brought in a local street dog, and she started suckling the tiger cubs. I often find that I have so much fascinating archival material on hand that I don’t have to search for anything to put in – I have more than I can use.

You have a new book coming out in September 2023 called Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India’s Cities. What is it about?

Yes, this is a book written by me and Seema Mundoli, my colleague. When we wrote our previous book Cities and Canopies, which was about trees in Indian cities, our editor at Penguin – Mansi Subramaniam – approached us with a book idea to write about rivers in Indian cities. After thinking about it for a while, we agreed to write a book but not only about rivers. In our book, we have short chapters diving into different aspects of water – wells, mythical beasts and water monsters, music and songs around the lake, the ecology of restoration, water warriors, how lakes and water bodies have been used for transportation, and so on. There are also short chapters on cities like Kolkata, Udaipur, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Bombay, Delhi – cities whose histories are closely tied to water.

We try to take off our scientist hats and relate to how people think of water from many perspectives: ecology and culture, science and spirituality, and at the core, the idea of organising communities around water. We cover a range of topics, from issues of justice and equity, to who gets the water in an Indian city, to the ecology, geography and chemistry of water and so much more – maps, mythology, music, history and everything else you can think of. Writing this book was great fun.