A peek into the IISc Archives and the world of archiving

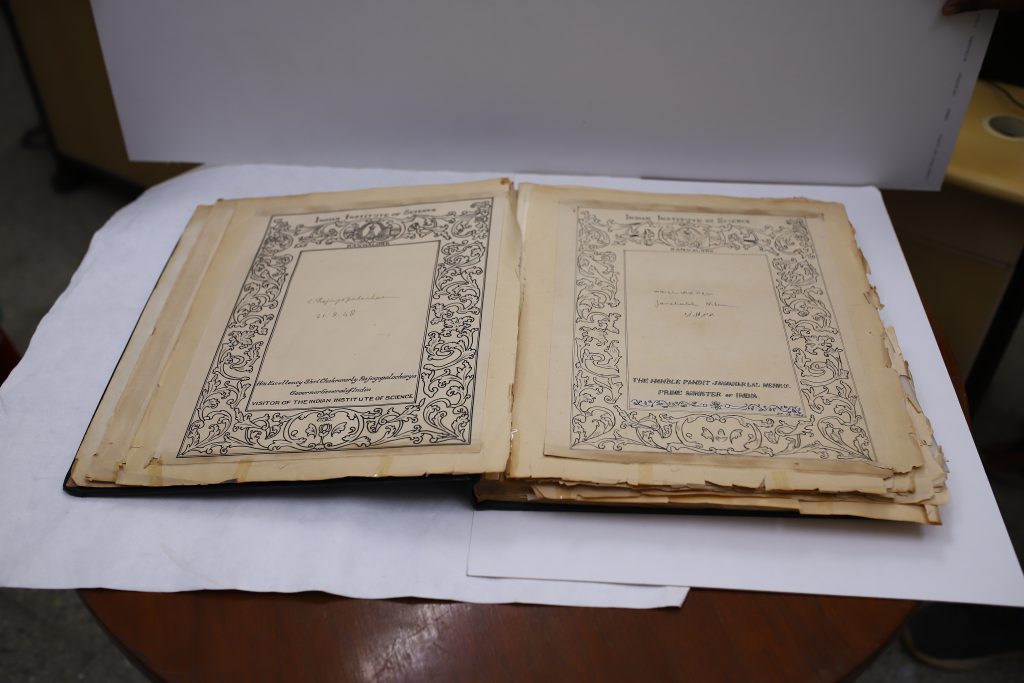

Among the IISc Archives’ many treasures is a large, heavy book called the “Distinguished Visitors Book”, a record of signatures from famous visitors to the Institute from 1948 to 1973. To look at, it is a worn book with crumbling pages onto which smaller sheets with signed names have been pasted – on the face of it, not an impressive document. But reading the names in it gives one an enormous sense of history: Jawaharlal Nehru, who visited IISc as Prime Minister of India in 1948 and 1951, and signed his name in Hindi, English and Urdu; Nikita Khrushchev and Ho Chi Minh, communist leaders of the USSR and Vietnam respectively, who visited IISc separately in the 1950s; Queen Elizabeth of England, who visited IISc in 1961 and signed her name “Elizabeth R” – the R for Regina, which means queen in Latin. There’s even an entry by the mountaineer Edmund Hillary, who visited IISc in 1987 as the Commissioner of New Zealand in India, and wrote, “A magnificent Institute – although I am a non-academic!”

What is the value of this crumbly old book, and why do we keep it in the IISc Archives? What purpose do archives and archival material serve, and why are they important to us? These signatures tell us not just of the people who made them and their stature, or the timing and purpose of their visits. They also tell us, among other things, about the Institute, its standing in India and the world, and the historical role of scientific research in international relations.

What is an archive?

An archive is a space for the preservation of records and material for their long-term value. It is a “documentary by-product of human activity”, according to the International Council on Archives (ICA), therefore providing a direct window into past events. Archives can be physical, containing items such as books, reports, letters, notes, photographs, objects and artefacts. They can be digital too, documenting human life that is increasingly lived online, or making digital copies of archival material available for reference. They contain primary sources of information that can give us insight into the actions and decisions of governments, institutions, communities and individuals, and at the same time serve as a repository for our memories.

However, an archive isn’t just about keeping a bunch of cool old stuff in one place – it’s important to record material while preserving the context in which it was created and to be able to show how it is connected to its source. Where possible, storing material in an archive also involves being able to provide a complete picture of how and why it came into being. The job of ensuring this falls to archivists, who are prescribed a code of ethics that includes protecting the authenticity of documents and ensuring “widest possible access” to the material within their archive.

Archives contain primary sources of information that can give us insight into the actions and decisions of governments, institutions, communities and individuals, as well as hold our memories

Archivists are also required to document their own work and decisions in the archive (and do plenty of record-keeping about record-keeping!). For instance, the decision to accept or refuse a set of letters, or to repair a group of fragile papers, or to deny access to a particular item, has to be documented so that the archivist’s actions can be understood. S Ponnarasu, Archive Project Leader at the Archive of IIT Madras, says that of all his tasks as an archivist, the hardest is appraising documents and deciding what to keep (or not to keep). As the Archive of IIT Madras is in the process of being set up, decisions need to be made – and recorded – about which documents to retain and how long to retain them for. “I can’t anticipate what researchers in the future might want to look for,” he says. “I find the appraisal part of the archival process the most complex, requiring my full attention.”

Although archives can contain valuable material of historical importance, an important aspect to remember is that archival material doesn’t necessarily represent the “truth”. The ICA cautions that material in an archive ought to be seen “only as a contemporaneous record from an individual or organisation with a particular level of involvement and point of view.” It goes on to suggest that users of archives – the general public, historians, researchers, students and so on – should be aware of this context when we interpret the material in these archives. It adds that we must also be aware of how our experiences and culture affect the way we ‘read’ an archival resource.

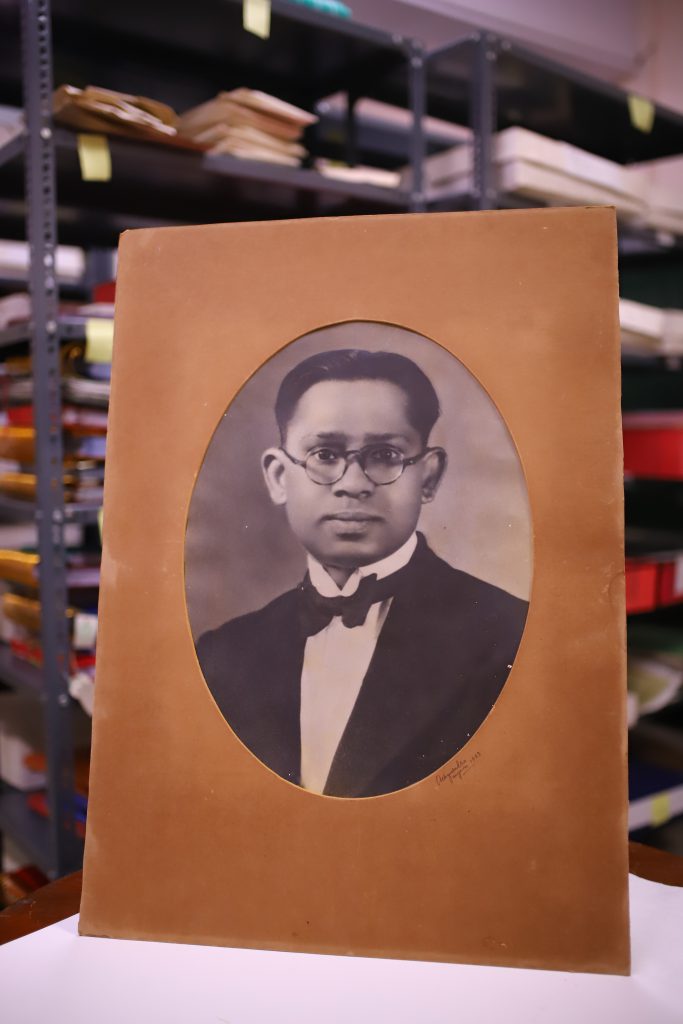

Where archives do exist, they don’t always provide a complete or exhaustive picture. Arun Chandrashekar, a biochemist in his 60s, has been trying to find out more about his grandfather, who was also a biochemist – and a rather famous one at that. V Subrahmanyam was Chair of the Department of Biochemistry at IISc in the 1930s and 40s, and went on to head the Central Food Technology Research Institute (CFTRI) in Mysore. Arun’s mission to document his grandfather’s work and other significant food technology research from that era is both a biochemist’s quest and a personal one. “It’s been a very tough journey,” he says, talking about his four-year search for records and primary documents across institutes, which has been physically taxing. He has found some material from speaking to people who knew his grandfather directly, some material that he gleaned from the Internet, and a little from the IISc Archives. But so much remains to be found, he says, and the lack of record-keeping in India and the dearth of archival material has proven a huge roadblock to his efforts.

How is archival material protected?

Because archival records offer such valuable insight into human activity, preserving them is key. As archival material such as letters, photographs and books can be old or fragile, several precautions need to be taken while storing and handling them. Items may need to be stored in a room that is temperature- and humidity- controlled, as large fluctuations in both can cause damage to the fragile material over time. They will also need to be kept in acid-free containers, and in conditions that are free of pests such as rodents and insects.

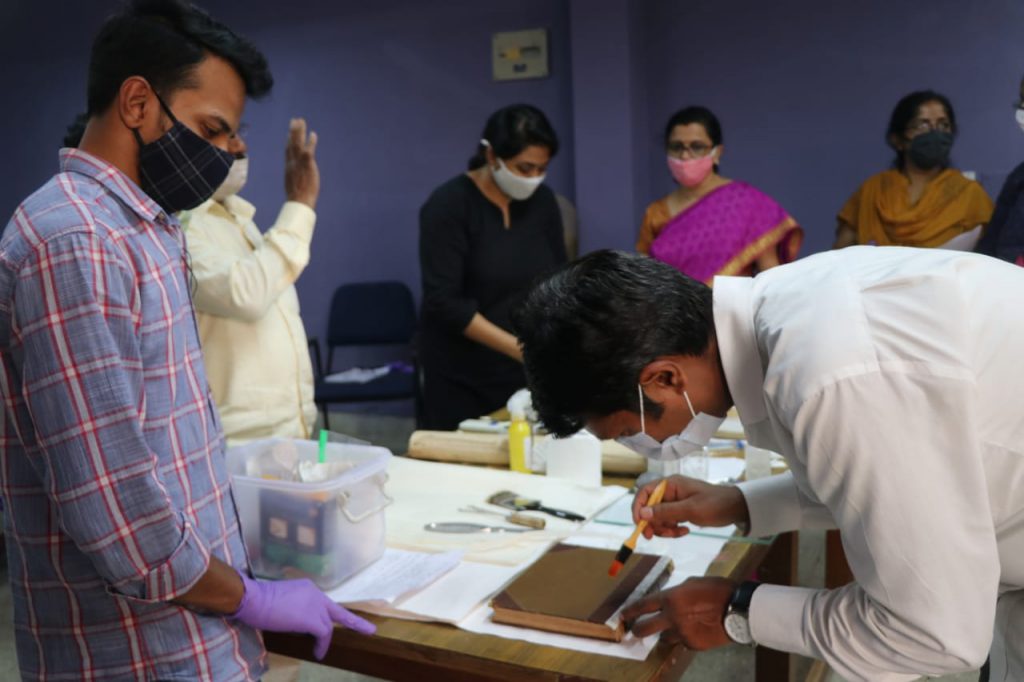

At a workshop held in November 2020 by conservators at the INTACH Conservation Institute, the staff at the IISc Archives were trained in preventive conversation – which means taking measures to avoid damage, rather than taking measures to repair damage after it has happened. We were shown the importance of maintaining ideal conditions in the archives, such as the right temperature, humidity and light; pest control, and the importance of keeping the area dust-free. We were also trained to use acid-free boards to transport fragile papers, clean the dust off documents by gently rubbing them with eraser dust using small cotton wads wrapped in lens tissue, to smooth out creases using de-ionised water, blotting paper and weights, and to mend tears or holes in documents using starch paste and Kozo tissue.

However, the training we received was to handle minor problems in the archives: for heavy duty work, there is no substitute for a professional conservator trained to restore documents, photographs, paintings or other items, depending on the archive’s needs. Multiple debacles in the art world with outcomes unfortunately similar to Mr Bean’s version of ‘Whistler’s Mother’ – like an amateur painter’s botched restoration of a Spanish church fresco of Jesus now infamously known as “Monkey Christ”– have shown just how important professional conservators are.

The conservation of physical objects also extends to audio and video recordings. While it is important to preserve material in its original form, it may also be necessary to update the format in which they are available as older forms of technology become obsolete, so that the content remains accessible to users of the archive.

How can archives be accessed?

In an archive, it isn’t enough to simply preserve material: providing access to the material is equally important. To make this easier, all the material is listed and described in a way that explains the content and context of what is in the archive. Archival records are typically maintained according to “provenance”, which means that all of the material that originated from a single source is kept together, so that the context for individual documents is not lost. The convention for describing archival material may differ from country to country, however, there are broad recommendations for a universal template. The ICA recommends the General International Standard Archival Description, known as ISAD(G), to be used either alongside or as the basis for national standards.

Every item in an archive is assigned a number or code based on the group they belong to. These codes and descriptions of the material within an archive together form “finding aids”, which help users to understand the way an archive has been organised and to locate material within it. The IISc Archives has been working on building a finding aid, with the goal of completing it by the end of this year.

The way that material is described, and the keywords and metadata assigned to an item in an archive, can play an enormous role in whether the item is accessible to the user of the archives or not. “One of our jobs as archivists is to ensure we describe and contextualise the object in such a way that users have multiple entries into it,” says Venkat Srinivasan of the Archives at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in Bangalore. He sees the object in an archive as being like a castle surrounded by a moat; the castle remains empty unless someone – “like the occasional historian” – attempts the strenuous task of swimming across the moat. When an archivist provides adequate context to an object, he says, it is like opening multiple drawbridges so that different kinds of people have multiple ways of getting into the castle.

Sometimes, even historians who attempt to swim across the moat find themselves with no way in when there are errors in the finding aid. Savithri Preetha Nair, historian and author of the forthcoming book Chromosome Woman, Nomad Scientist: EK Janaki Ammal, A Life 1897-1984, says that her search for Janaki Ammal’s letters of correspondence led her to one of the world’s leading university library-archives. Typing the name “Janaki” into their system didn’t reveal a whole set of related correspondence that had been filed under “Jawaki”, a typo that had inadvertently crept in. Trying alternate search terms and finally going through all search results for just “Ja” eventually led her to the letters she was hoping to find. “I told them about the error so that they could correct it,” says Preetha. A simple spelling error at the time of data entry very nearly rendered those letters invisible to anyone trying to search for the name of the renowned Indian botanist.

Access to archival material can also be dictated by institutional policy (where records may be classified, for instance), or by privacy laws, issues of ethics or the personal wishes of donors. This was one of the focal points of discussion during International Archives Week in June 2022, where members of Milli, an archives collective, met at NCBS to discuss issues related to ethics, law and archival standards with the aim of developing resources and guidelines that can be used by archives in India. Another key area of discussion was the creation of a common technology platform, which people trying to access archives could use to annotate archival material online, adding context to this material and thereby making it more visible to other users.

So why archive?

Historically, countries and institutions have had archives mainly as tools for record-keeping and administration. Archives are central to governance, though this has a fraught history – colonial governments, for example, have collected information about their subjects as a method of control. And decisions about what is deemed “worthy” of archiving can be deeply subjective. However, having a good archive can also help to hold governments accountable to their citizens. According to the ICA, “well-managed archives and records are the means by which a country can understand the who, when, where, how and why of government actions. They enable the delivery of human rights and the ability for a government to explain and defend its actions.”

Apart from their value in governance, archives and archival material are also vital to culture and memory. “Archives enable a diversity of stories,” says Venkat. “Every object around us is a by-product of a variety of stories – some by luck, some by process, and some by deliberation.” Archival objects, he says, are not of value solely for their content, but also for the things that they are symbols of. A recent example of this is a historic dress that actress Marilyn Monroe once wore in the 1960s, which modern celebrity Kim Kardashian wore again during the Met Gala in May 2022 – a decision that sparked alarm and criticism from conservators and museum curators who were concerned that even those few minutes for which it had been worn might have caused permanent damage to the iconic dress. Kevin Jones, curator of the museum at the Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising, illustrated the historical value of the dress when speaking to the LA Times. He told the publication, “Our job is to get the garment to the next generation with as little damage as possible, so that 500 years from now, these objects are around to talk about our history, our collective history as people, design, technology, arts and culture. […] All of that gets blended into a single object, in this case a garment. It represents a moment in time.”

In showing us these moments in time, archives help us to build a picture of our past, and thereby to reimagine and shape the future.