The first example of academic entrepreneurship from IISc was an attempt to revolutionise personal computing in India

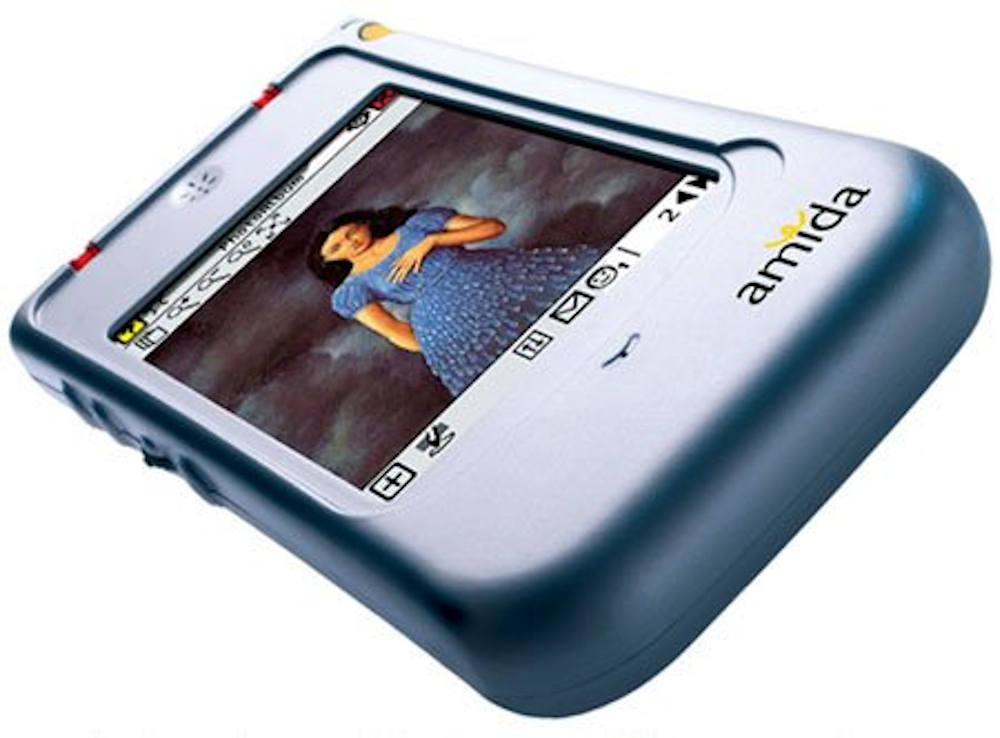

(Image courtesy: PicoPeta)

The year 1998 was the calm before the storm. India had just declared to the world that it had successfully tested weaponised nuclear warheads. The then Prime Minister, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, congratulated the scientists and engineers involved in the mission for their success. The Kargil War, which would sorely test India’s military and technological might, was still a year away and the country had not yet registered the birth of its billionth citizen.

Over 180 million students were in school and only a lucky handful had just become familiar with computers. The digital divide was growing. In this backdrop, during the IT.Com event of October 1998 – touted as the first large-scale IT expo in the country – the Bangalore Declaration on Information Technology for Developing Countries was released. One of the goals of this declaration was to make a Simple Inexpensive Mobile comPUTER (SIMPUTER) to provide access to information technology for every citizen, regardless of their social or economic status. This spurred four faculty members in the Department of Computer Science and Automation (CSA) at IISc – Vijay Chandru, Swami Manohar, Ramesh Hariharan and V Vinay – to imagine and develop a low-cost handheld computer, one that could be accessible for everyone. Simputer was not the only innovation that came out from the partnership between the four. While Swami Manohar and V Vinay were setting up a company called PicoPeta to market the Simputer, Ramesh Hariharan and Vijay Chandru were also building a genomic company for personalised medicine called Strand Life Sciences.

In terms of technological innovation, Simputer had an impressive list of firsts. It was the first Linux-operated handheld device with writing capabilities, the first handheld device to have a USB master port and the first to have an accelerometer.

But the Simputer did not become a commercial success. Its development reflects the growing pains that the Indian entrepreneurship ecosystem faced during the early 21st century. In some ways, it also kickstarted the concept of faculty entrepreneurship at IISc.

Ahead of its time

“The most significant innovation in computer technology in 2001 was not Apple’s gleaming titanium PowerBook G4 or Microsoft’s Windows XP. It was the Simputer,” journalist Bruce Sterling wrote in the New York Times on 9 December 2001.

When it first came out, the Simputer was truly ahead of its time. It had capabilities such as intuitive touch and allowed users to write using a stylus – a feature that was only widely commercialised 15 years later by Samsung in their Galaxy Note smartphones. Simputer had a simple handwriting recognition software and text-to-speech software built into the device.

When it first came out, the Simputer was truly ahead of its time

A crucial feature of the device was the accelerometer, which is necessary for resolving orientation and responding to a user’s gestures. This feature, which was introduced by Apple in their iPhones only in 2007, was already present in the Simputer. A German article that described the patent war between Apple and Samsung about the use of the accelerometer quotes the Simputer as prior art. “Diese Idee wurde nicht 2007 erstmals von Apple implementiert – sondern 2004 von einem indischen Konsortium im “Simputer” [translated] This idea was not implemented by Apple for the first time in 2007 – but in 2004 by an Indian consortium in ‘Simputer.’” There were great expectations that the “Sub-10K Simputer” would disrupt the domestic market and become the device of choice for millions of Indians.

Yet, the Simputer was not a commercial success in the same sense as the iPhone or the Samsung Galaxy smartphones, which went on to become household names. “There is no way the Simputer could have succeeded,” says Vinay. “After running a business for 20 years, today, there is no way I would have started anything like the Simputer.”

The main challenge for Simputer’s founders, Vinay explains, was that anybody with deep pockets could subsidise it. Large companies like Microsoft or Hewlett-Packard could afford to build something similar and distribute it free of cost.

The other challenge was that venture capitalists did not find it as “exotic” as something like Strand Life Sciences at that time, points out CS Murali, who is currently the Chair of the Entrepreneurship Cell, Society for Innovation and Development (SID) at IISc. Murali was involved with the Simputer as a partner in a venture capital firm called Connect Capital, which also invested in Strand Life Sciences.

Murali attributes the lack of Simputer’s commercial success to two factors. “For any product to succeed, you need an ecosystem. For hardware, you need people who would build software for it. For Simputer, there was no meaningful ecosystem or developers who would develop applications around it.” Today, a lot of products are given away for free in the hope of generating an ecosystem and the revenue comes from usage; some examples are open-source projects like Arduino and Blender. While such moves would have been easy for bigger and more established companies to make, it was not feasible for a startup like PicoPeta.

The other reason that it did not take off, Murali feels, was its aesthetics. The first devices were “clunky and didn’t look good,” he says. “A product can have many useful features, but it can create a negative impression based on its looks.”

The silver lining in Simputer’s journey is that it generated a lot of buzz and became widely known in the world of technology.

Vinay points out that PicoPeta, Simputer’s parent company, was the place to be for anyone who was interested in computers and information technology. “Every investor came to visit the PicoPeta office. It was the only piece of technology to be showcased in Bangalore at that time.” When Bill Gates visited Bangalore in 2005, he was asked about Simputer’s potential. Senior design engineers of the iPhone had also looked at the Simputer for ideas, according to Vinay. “Everybody took notice of it. It was an idea that everybody was aware of.”

Running a business

The Simputer and the people involved in its development changed things at IISc too. This venture by four faculty members was the first such attempt at entrepreneurship from the Institute. Murali explains that the company was not incubated in the true sense as the concept of IISc-incubated startups did not exist at that time. In the early 2000s, the concept of faculty entrepreneurship, where a faculty member uses their expertise to create marketable products, was in its nascent stage and considered a very bold move. Simputer’s founding generated great interest even within the IISc community. The faculty members’ decision to take such a risk led the Institute to outline a well-defined policy for such ventures and take steps to figure out how entrepreneurship would fit into the Institute’s charter of research, according to Murali. Their endeavours, therefore, paved the way for future faculty entrepreneurs.

Vinay credits Goverdhan Mehta, the former Director of IISc and HP Khincha, the former head of SID, for their help in encouraging academic entrepreneurship. As there was no precedent and the administration was also new to entrepreneurship, they imposed some amusing rules, Vinay remarks. “We were not allowed to take salary from the company to save our souls from corruption.” They set up an office for PicoPeta in Sanjay Nagar, close to the campus, in the same location where Strand Life Sciences was also established.

The faculty members’ decision to take such a risk led the Institute to outline a well-defined policy for such ventures

During the heady early days, the founders also managed to raise an impressive capital of about Rs 4 crore. This money was to be used to develop the device, pay salaries to the engineers and for rent. “What we did with the 4 crore is astonishing,” Vinay says. “We survived for five years and we did not default on a single payment, either rent or salary. We were burning 25-30 lakhs a month – essentially, I had 2 months’ worth of salary at any time. And I did not lose sleep at any point.” Excitement about developing a new technology kept them going ahead at full steam. “Today, I would not do it,” he admits.

In 2002, Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL) announced an alliance with PicoPeta to market the devices as BEL-PicoPeta Simputers. The price of one unit was set to be Rs 13,000. Eventually, PicoPeta was acquired by a Mumbai-based internet product company. Changes in BEL’s management also brought the production of the devices to a stop. Vinay adds, however, that there are probably a few devices still around. “Several individuals do have the devices. I suspect the battery would have died out on most of them. I know that Manohar had a device that worked as recently as two years back (just before the pandemic).”

Although its production was stopped, there is no doubt that the device has left its mark. Vinay brings up the examples of Barbara Liskov and Alan Kay, computer scientists who conceptualised Object Oriented Programming. The languages they developed, CLU and Smalltalk, did not have the same impact that C++ and Java had later in the 1990s. “You can ask, ‘Did they make a difference at all or not?’” says Vinay. “Early ideas do make a difference. We have inspired people and that’s the only thing that matters in the end.”

Debayan Dasgupta is a former PhD student from the Centre for Nano Science and Engineering and a former science writing intern at the Office of Communications, IISc