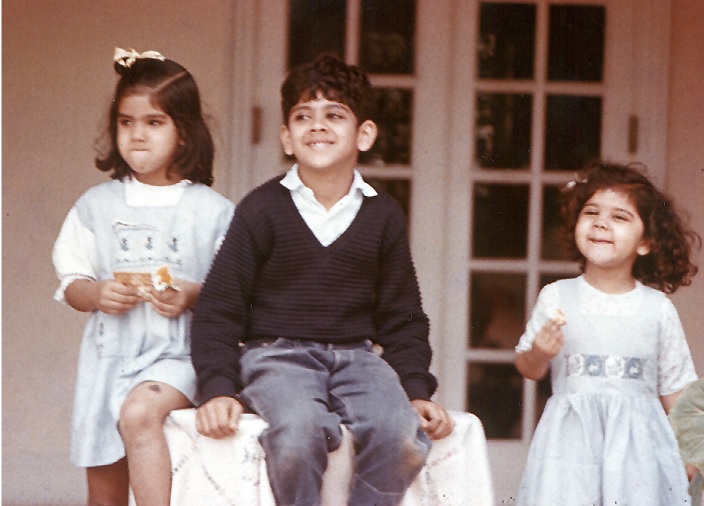

Ahead of Satish Dhawan’s birth anniversary on 25 September, his daughter Jyotsna writes about her childhood on the IISc campus, life beyond, and her father’s indelible presence

In the 1960s, while our parents (mostly fathers) worked away in labs and offices, libraries and classrooms, the children of IISc staff (mostly barefoot and unsupervised) explored that magical campus, wild and mysterious as it was in those days, and revelled in the natural world. That world is still in us, we return to it in dreams, it is the source of our imagination. As Borges wrote, “Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am the river.”

In this essay, inspired by the 100th year of my father’s birth, I recall an incident from my work as a cell biologist that simultaneously triggered return to my childhood in that paradise, and propelled me towards a new beginning in my research.

Dependent relationships

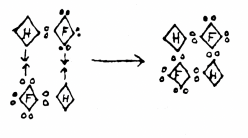

“A triskelion is a Buddhist meditational symbol,” writes Victor Mansfield in ‘Time and Impermanence in Middle Way Buddhism and Modern Physics’. “It resembles three commas chasing one another round a circle, and represents the three aspects of Dependent Relationship which give existence to all functioning things. The Buddhist teaching on Dependent Relationship states that phenomena exist in three fundamental ways. Firstly, phenomena exist by dependence upon causes and conditions. Secondly, phenomena depend upon the relationship of the whole to its parts and attributes. Thirdly, and most profoundly, phenomena depend upon designation by the mind. The appearance of motion of the three swirling blades symbolises that the impermanence of all compound phenomena arises from these three ever-changing relationships.”

The art and craft of cell culture

For about a hundred years, scientists have been able to dissociate cells from a chunk of tissue and keep them alive in a dish, watch them multiply and specialise, and in so doing, understand about the molecules that control all these behaviours including how cells organise into tissues, communicate with other cells near and far, how they die and how they escape normal controls to become cancerous…

The experimental protocol for culturing cells engages the practitioner in a sort of restricted dance form. You are mostly seated in front of a glass-fronted biosafety cabinet that protects the sterile cultures from your microbe-laden breath. The key to preventing air outside the hood from mixing with the sterile atmosphere around the cells is a vertically flowing air-curtain, a laminar flow. Inside the cabinet, there is space for petri plates and tubes, bottles of media and sterile pipettes for dispensing nutrient broths that bathe the cells which grow clinging to the surface of a plastic petri plate. At the back of the cabinet, another vertically flowing air sheet reinforces the sterile atmosphere. You must reach through the airflow behind the glass front to perform your tasks, and if you are not in rhythm, or have too many things in your hands, you can spill or contaminate your cultures. Primarily, the tip of the pipette that dispenses liquid must never touch any surface outside the sterile media bottle. So, an elaborate set of coordinated hand movements is required to open and close dishes, uncap bottles and pick up small test tubes, all the while staying aware of the need to keep things separated and clean. Moving liquid around, transferring cells from a dish where they have grown too crowded for comfort, and keeping your hands from entangling themselves in your pipettes – those essential extensions of hand and mind – requires that your consciousness be focused simultaneously inside the plate with the cells, while double-checking all your actions by examining their consequences under the microscope. And above it all, in your thoughts floats the experiment that you are doing to probe the cell interior, asking how does the cell perform this or the other task, marvelling at the beauty of the precisely organised subcellular milieu…

The gleaming steel and glass of the cabinet, the pink and orange culture media, the rapier-like pipettes, the living moving metabolising cells tantalisingly close under the microscope, are all a product of the art and science of tissue culture.

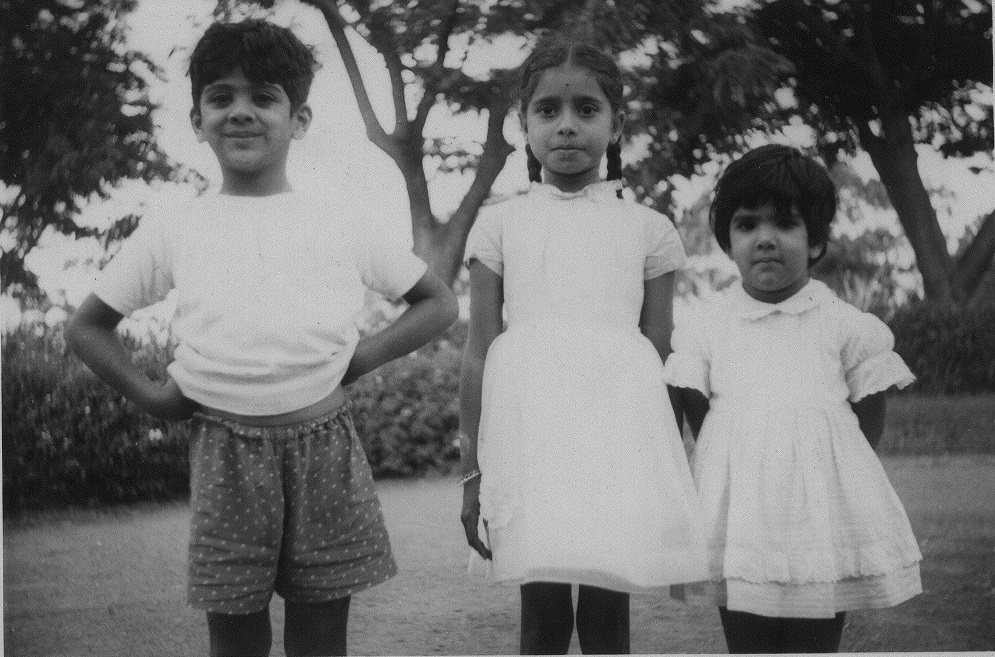

of purified muscle cells, 2014 (Photo courtesy: Jyotsna Dhawan)

North Carolina, August 2003

I am in a crowded basement lab, late one summer evening, seated at the laminar flow hood, isolating progenitor cells from the skeletal muscle of mice, performing my familiar solitary culture dance, moving to a practiced music. There are time-bound experiments to be done, a grant proposal to be written, pressure and questions swirl around me, including the most pedestrian – why have I pushed myself to do all this while working so far from home, as a visitor in this American lab? My host lab has engineered transgenic mice that I need to test a hypothesis raised by my earlier work. I am unable to import the mice to my lab in Hyderabad due to long regulatory paper-tangles, so I have exported myself. I could just as easily be at home in my peaceful messy house, chatting science or lab gossip with my husband; I could be in my own lab, arguing with my students to do something my way instead of their way, but here I am, rooming in a long-stay motel on a rural highway in North Carolina, working to a crazy schedule to complete this work in the month given to me by my travel fellowship. My time is nearly up, I have not completed the experiments, nor have I completed writing the proposal for funding my group’s research for the next several years…

I am an experimental cell biologist. What makes my heart beat faster and my brain sing is figuring out how muscle stem cells stay in a dormant state. What, you say, why is that important?

Skeletal muscle is a wonderful tissue, contractile and strong – and it forms more than a third of our body mass, allows us to move, breathe, and express emotions through the 42 muscles in our face. Think of the immense range of emotions conjured by a Kathakali dancer’s dramatically mobile visage! Muscle is also a major contributor to our overall metabolism, because it burns nutrients to create energy for movement. Working continually whether we are at rest or actively exercising, with time, muscle tissue wears out and needs replacement. Luckily for us, we have a batch of reserve cells that evolution has set aside exactly for this purpose. These are called muscle stem cells, and they regenerate damaged tissue. Defects in muscle repair can cause devastating diseases, spurring labs across the world to understand the molecules and cells that normally control how muscle regenerates. Muscle repair also declines as we age, but remarkably, this decline can be mitigated by regular exercise, which keeps muscle tissue supple, and the rare stem cells tuned for action.

To isolate living cells, I have dissected out the muscle from a mouse, and must manually chop the tissue into very small pieces with two scalpel blades before adding enzymes to release the stem cells. The mouse is no longer alive. Its cells, however, are still fizzing with metabolic activity, capable of growth and division, immortalising their mousely past, a testament to their host’s instant in time. Each muscle requires 15 minutes of finicky precision chopping – picture a 3 millimetre-long onion being diced very fine (Thanks to Tom Rando for that evocative image of the tiny onion, articulated during a daylong session of muscle chopping when we were postdocs in the 90s). I have been doing these experiments repetitively since 7 in the morning, and am nearing exhaustion, close to giving up. I berate myself for imagining that working half-way around the world would be a practical way of addressing this question. My mind flits between negativity and self-doubt as I mince the tiny piece of muscle tissue mechanically, my own muscles tiring from the stiff position I have had to maintain for hours. A little scraping sound disturbs my reverie, but I ignore it, forcing my own screaming arm muscles to keep dicing. The sound stops, then starts again, persists, and out of the corner of my eye I see a little silver object spinning around on the surface of the perforated laminar flow barrier. I stop mincing and stare, unsure of what I am seeing…

The little silver foil packet sputters, then swirls around on its axis in the flow of the sterile air curtain, lifts gently and precisely off the perforated steel flow cover to a height of about two inches, then settles back down momentarily, swirls again, lifts perfectly off in a little repetitive dance…

Just by chance I have opened the aluminium foil package of the scalpel blade such that it creates a perfect triskelion with arms of equal length, and just by chance I have placed it at a serendipitously correct angle in the laminar flow, leading to this propeller action in the stream of air. Placed at any other angle, it would not have behaved in this fashion. As it is placed, it catches the vertical airstream in the curtain exactly right, it flickers and starts to rotate, then goes into a perfect loop of stable smooth rotation, lift, then loss of lift, obeying gravity, settling back down, again perfectly, to catch the flow, and repeats.

This goes on for a full minute until I move my arm and the angle of the flow changes. Word associations flood my mind: aerofoil, lift, drag, aerodynamics, Reynolds number, Bernoulli, fluid flow: I know none of the scientific bases for any of these, but these words swirled around my childhood, and settled in my imagination, accompanied by my father’s excited voice and sparkling eyes, you could always hear the smile in his words; Satish fills my spirit and I float back to Bangalore.

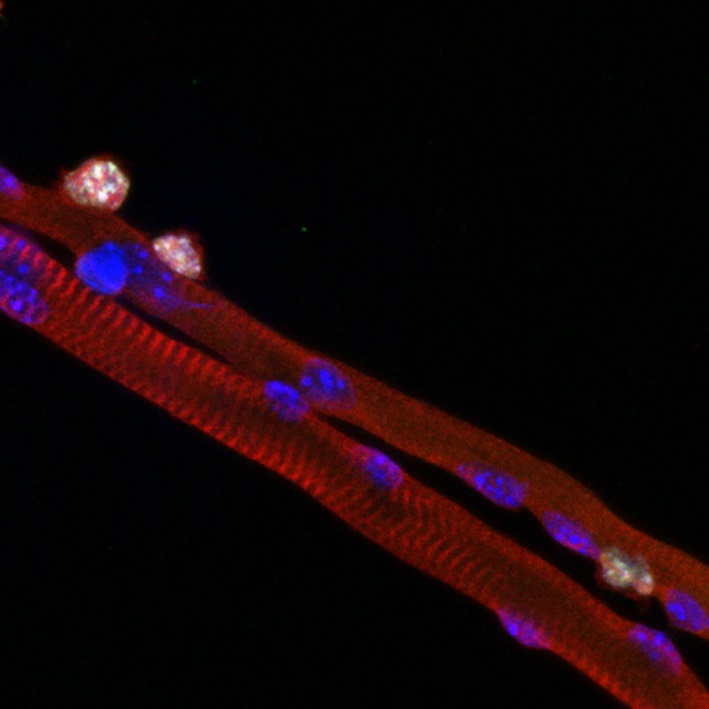

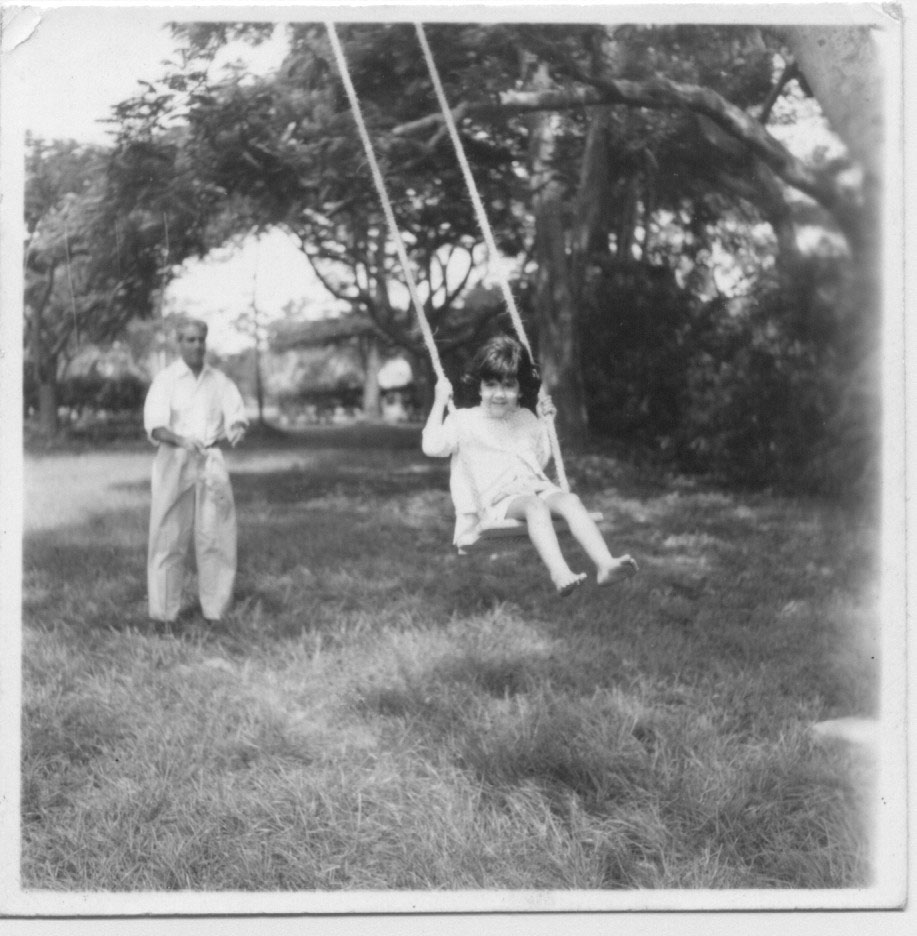

Bangalore dream days, 1962-78

The idyllic wild campus of IISc in the 1960s offered a fund of aerodynamically active natural objects to anyone who cared to look. On our rambly walks through that paradise, Satish would pick up winged seeds from the bursting mahogany pods, spiral purple flowers from the petrea creeper and the little parachutes of dandelion seeds, playing by flicking them into the wind at distinct angles, watching their flight with glee and satisfaction, encouraging us to do the same, and describing their descent.

He is observant about the tiniest phenomenon linked to air movement, relishing the chance to revisit and revel in it. We are walking in another campus near IISc, passing a creeper-covered wall. Only one out of the thousands of near-identical leaves catches the slight breeze such that it goes into a repetitive flapping, fluttering motion; aeroelastic instability, he says, pleased; then he tells me about advanced aircraft wings and how they must deal with this eventuality. I nod with little comprehension, but it settles into the soup.

I am little; we wash the car on Sundays, Satish making it into a fun thing for us kids. With his rolled up trousers, and wielding a gushing garden hose, he makes little rings with the water flow, the stream broken into bursts as we clamber over the sides of the ancient Morris Minor, water streaming into droplets that catch the morning sun, delighted to be getting our clothes wet with permission; a glorious Bangalore day; someone steps on the hose, he smiles and points out the momentary sputter in the flow.

On summer evenings, when we are too rambunctious to be in the house before dinner, we are bundled into the venerable Morris, the cracked canvas roof rolled down, we are instructed to bend our heads back over the seat and scan the sky for Sputniks, as Satish drives slowly around campus in the deepening dusk, velvety flying foxes winging out of the drumstick trees. I see it, I see it, we all claim at every glint in the sky, letting our imaginations reel away into space, pretending that we are Gagarin in the little white and red plastic rocket given to us by a visiting Russian.

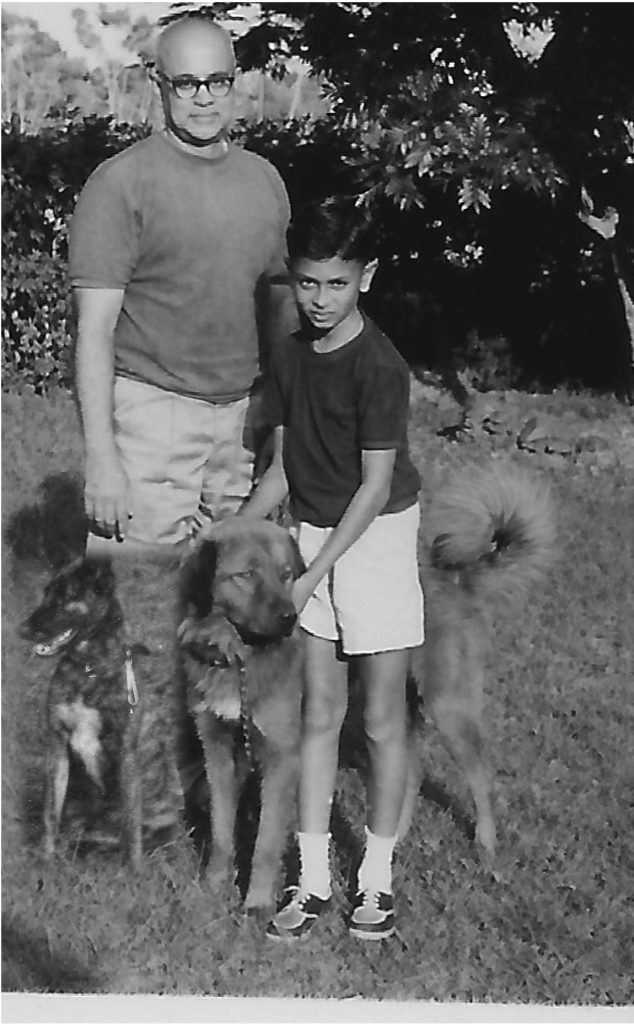

(Photo courtesy: Dipanker Banerjee)

I am much younger, maybe 5, we are wandering along the unpaved campus paths, he squats down to my height and shows me a tiny conical funnel, a minute depression in the chalky soil, small orange sand grains skeetering down the steep side – an antlion sitting in the base is trapping its bait. Years later we are on a similar walk, another antlion, he explains the geometry of the perfect little trap, I half listen, lost in the trilling manic call of the barbet and my own thoughts.

Rain

Cathartic, sensuous, fecund, sacred

Chasing barefoot, a twig in brown gushing gutter

Childhood drenches me

My sister and I walk with him after a sharp April downpour, a delicious deluge of flood water stained orange-red with the iron-rich Bangalore soil, swiftly coursing through the deep open gutters, lined with ancient Deccan granite; we stop at intervals to flick in leaves, flowers dropped by the merciless rain drops, sword-like seed pods from the gulmohurs overhead; we run downstream to catch our flotilla; Satish finds us more objects that give better swirl patterns.

I am not ready to sleep so I wheedle to accompany Satish to the Aero Department when he goes back to work after dinner; I first contemplate the big propellor on the side of the entrance thinking about the plane from which it came, and then press my nose against the perforated end of the wind tunnel, crossing my eyes to play with the Moiré patterns caused by the imperfect superposition of the double layers of wire mesh.

We are swimming in the newly refurbished gymkhana pool; for a whole summer we cling to the poolside beating our legs and trying to get afloat, dog-paddle ineffectually. Then we accompany Satish on his sabbatical to California, his alma mater Caltech; we have heard about Caltech with a reverence and joy in his voice ever since we can remember; those magical names – El Camino Real, Pasadena, those legendary people – Von Karman, Hans Liepmann, Anatol Roshko. We take swimming lessons, the open Californian attitude spurring our learning, and in a week we are more proficient than in the whole last summer. We are given lifesaving lessons, have to pass a test in which we must stay afloat for 10 minutes with our hands and legs tied, the technique for bobbing up and down without struggle by just letting our breath and lungs be our flotation devices gives us huge confidence; Satish is pleased.

Back in Bangalore, lying on our backs in the summer sun on the high platforms flanking the founder’s statue, we lazily watch the stately unhurried climb of the kites into the thermals over the IISc quadrangle. Walking home, a sudden gust shakes free the papery thin winged seeds of the Tabebuia argentea trees lining the avenue, a shower of parchment white. Running laughing through an evening field of ruby grass ruffled by the surface riffles of a Bangalore monsoon, stomping hard to make sure the snakes feel the vibrations and leave us alone…

(Photo courtesy: Jyotsna Dhawan)

North Carolina, August 2003

I gently set down my pipette and close the dish with the muscle sample, and laugh uncontrollably at the improbability of this levitating, rotating triskelion. Some peaceful energy returns to my bones, I complete my experiment. An hour later, I head back to the rural highway motel, and get down to writing. I finish the grant at 3 am.

Hyderabad and Bangalore, 2004-2009

Of the two tasks I struggle with in North Carolina, I never do publish the results of the experiments with the muscle cells from the transgenic mouse, but find out much later that I was on the right track. A colleague from Colorado follows the same hunch, does the right experiments, adds a line to the understanding of muscle progenitor cell behaviour and the molecules that regulate repair.

But I do get the grant – a larger source of funding than I can imagine at that stage of my career – it allows me confidence, flexibility and sweep in my work, enables me to buy sophisticated equipment, fund my students to travel to meetings. We find evidence for genetic programs that we had hypothesised, molecules that help dormant muscle stem cells stay potent for future activation. It sets me on a path quite different from the one I might have trod without the liberating influence of flexible funding. Beyond the financial support, I am drawn into a group of scientists who are asked to participate in larger programs – we encounter each other all the time, work together and progress as a cohort … a new horizon, still filled with wonder at the natural world, crystallised in a fleeting self-levitating triskelion moment when Satish’s presence sustained my flagging spirit.

Dedicated to that roving band of IISc kids of the 60s and 70s: Pitku and Amrita; Sudha and Chakrapani; Subbu; Jayanti and Arun; Radha, Sudha, Anu and Ramudu; Nannu and Pommy, Gowri and Indrani; Ravi and Yashoda; Chandrasumitha, Patanjali and Divyavardhana; Dippy and his fierce friends Bhute and Shakhi; Raghu and Malathi; Ramakrishna, Vasanta and Baba; Ganesh; Subbarao; Nina and Ashok; Maithreyi and Aditi; Ranjan, Alak, Palak and Anjan; Sridhar and Jayaram, and Goofy. May the force be with you.

My thanks to Vrinda Kumble and Vivek Dhawan for comments on successive drafts, and to Amrita Dhawan for permission to use her poem “Rain”.

Author: Jyotsna Dhawan is a cell biologist who as a child was fortunate to roam free in the untamed campus of the IISc as it was in the sixties, when Satish Dhawan was on the faculty of the Aerospace Department. She works at the CSIR-Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology at Hyderabad (https://www.ccmb.res.in/People/Research-Group/Jyotsna-Dhawan), and is part of a new effort to generate philanthropic funding to support life science research in India (https://ignitelsf.in/).