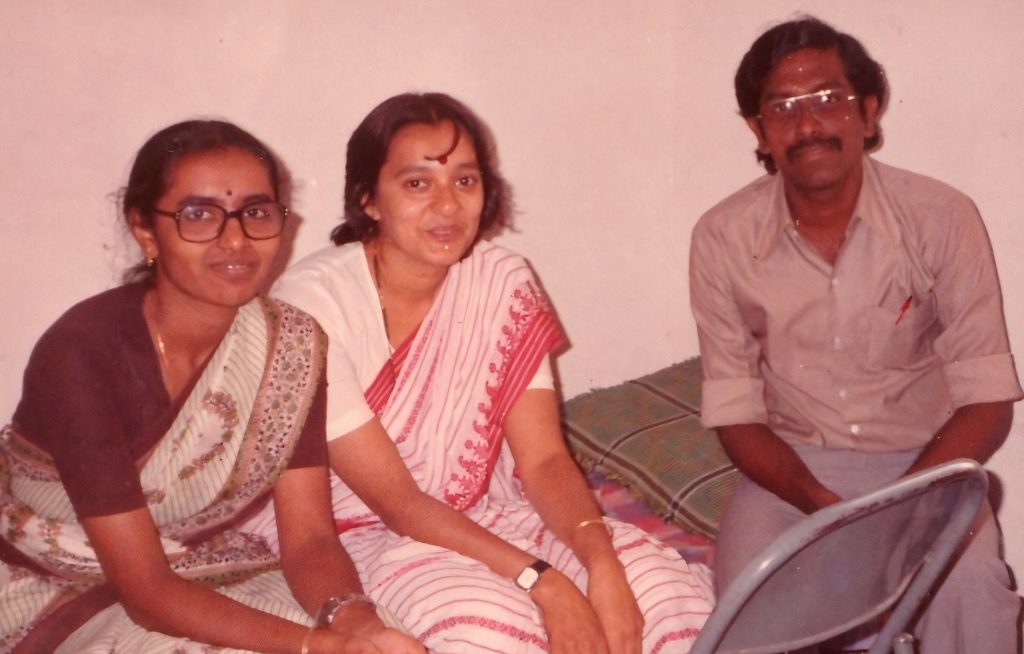

PB Seshagiri, Sandhya S Visweswariah and Varsha Singh talk about their academic journeys

There is no doubt that IISc attracts some of the best students in the country. But a few of them have come full circle, returning to the Institute – some even to the same building – where they took their baby steps into the world of research. As the Department of Biochemistry at IISc celebrates its centenary year, it is only fitting to turn the spotlight on the alumni who are now faculty members at other departments in the Institute.

The Biochemistry Department has come a long way since its inception in February 1921. It has moulded and nurtured some of the finest scientists in the country, many of whom have gone on to become institution builders, entrepreneurs, and industry leaders. And some of them have found their way back home – to the place where it all began.

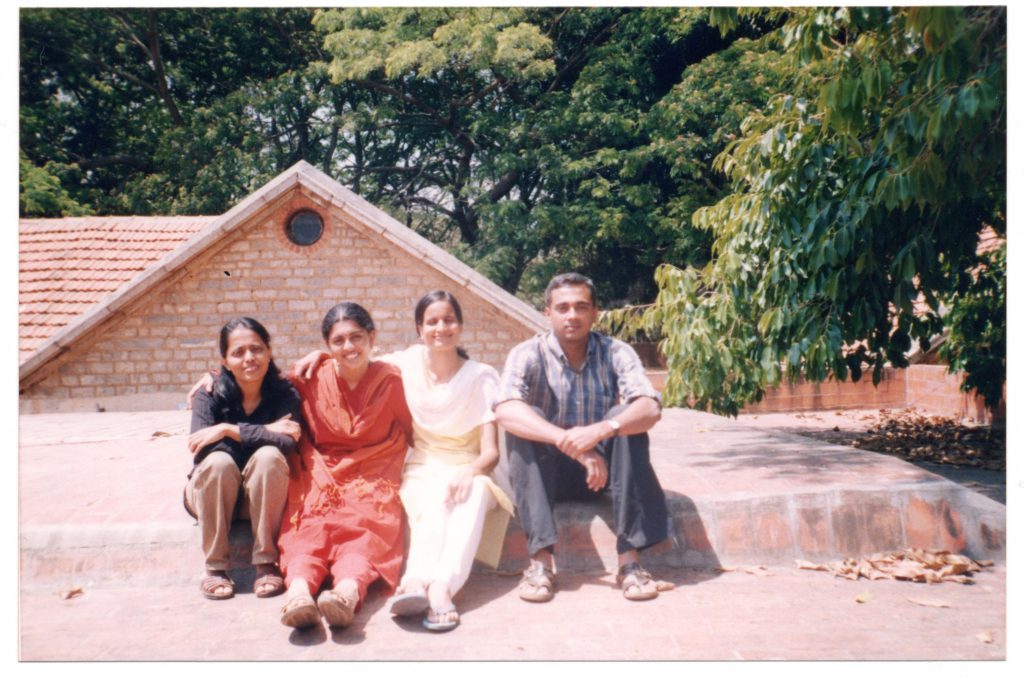

Three of them, currently faculty at the Department of Molecular Reproduction, Development and Genetics (MRDG), obtained their PhDs from the Biochemistry department – Polani B Seshagiri (Professor), Sandhya S Visweswariah (Professor), and Varsha Singh (Associate Professor). They are the only Biochemistry alumni among the current faculty members of the institute outside of the Biochemistry Department.

From student to supervisor

The academic journeys of Seshagiri and Visweswariah are remarkable. They completed their PhD from the same lab as contemporaries, returned to the Institute as faculty around the same time, and went on to become Chairs – a position that their PhD advisor held when they were recruited. Singh’s story is equally interesting. Academically speaking, she is a second generation alumnus of the Biochemistry department – her advisor, Utpal Tatu, who is still a professor in the Biochemistry Department, also did his PhD there.

Seshagiri and Singh only have words of appreciation and gratitude as they recall their student life in the department. The lectures hosted at the Biochemistry Lecture Hall, resource-sharing among peers and informal scientific discussions among students are themes that stand out in their reminiscences.

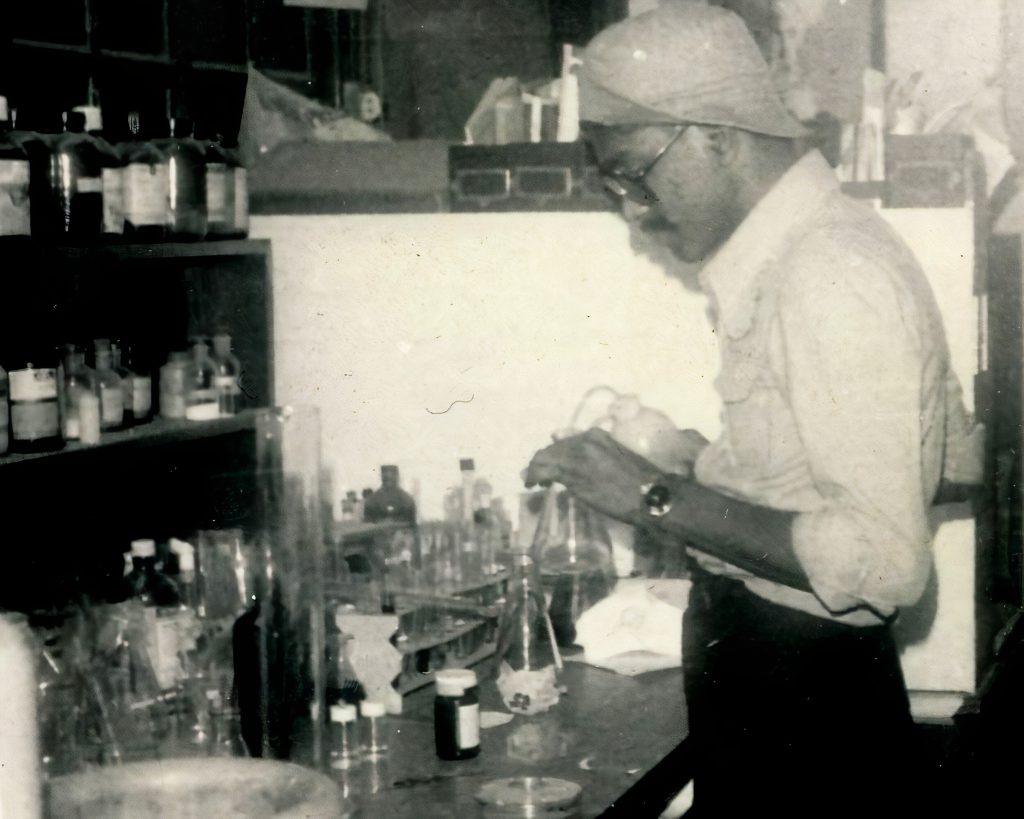

After his MSc in Clinical Biochemistry from the Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education & Research (JIPMER), Puducherry, Seshagiri joined PR Adiga’s lab for his PhD in 1980. It was his keen interest in endocrinology (the study of hormones and the glands that secrete them) that led him to join the lab. As a student, he learnt many experimental techniques from his seniors. He also had much to offer to his peers: animal handling techniques, injections and surgeries – some skills he had gained from his anatomy and physiology background at JIPMER.

Seshagiri remembers his peers in the department as a bunch of dedicated and enterprising students. “We worked very hard and shared resources and research workload. We had a feeling of togetherness, discussed ideas, and knew how to troubleshoot problems in experiments,” he says. “Most of all, we enjoyed great academic freedom.”

About halfway through his PhD, Seshagiri attended the Indo-US conference on Blastocyst Research organised by NR Moudgal, a professor in the

Department of Biochemistry at the time. And this would be a turning point in his career. “The workshop featured amazing demonstrations of sperm culture, embryo culture, embryo transfer etc, and fantastic lectures were delivered by stalwarts in the field,” says Seshagiri. “At that time, the most profound lecture was the one by BD Bavister, the architect of the first IVF-test tube monkey, Petri.”

In 1987, a year after obtaining his PhD, Seshagiri joined Bavister as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Three years later, he became an Assistant Scientist at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Centre (WNPRC). But all this while, he longed to return to India. “So, when the faculty recruitment for the newly founded Centre for Reproductive Biology and Molecular Endocrinology (CRBME) – which is now called MRDG – started, I applied and was selected,” he says.

Visweswariah’s experience with the department was quite different. After her Master’s in Chemistry from IIT-Kanpur, she moved to Bangalore with her husband who got posted here, and applied for a PhD in the Biochemistry Department in 1980. “The Department of Biochemistry at IISc was perhaps the most well-known biochemistry department in the country A lot of students aspired to do their PhD [there],” she says. Looking back, Visweswariah considers herself fortunate to have been selected there for a PhD, coming from a pure chemistry background. On G Padmanaban’s suggestion, she joined PR Adiga’s lab.

As she was married, Visweswariah lived outside the Institute and only spent her work hours on campus. “I used to come in the morning, do my work, and leave in the evening,” Visweswariah says. “But as a result, I could stay quite focused. I knew what I had to do, and I knew I had exactly so many hours to do it.”

Visweswariah remembers fondly that she found a great friend in Anjali A Karande, a postdoctoral fellow in Adiga’s lab at the time, who would go on to become a faculty member at the Biochemistry Department. “She lived very close to where I lived. So, we would come to the lab together every day and go back home together. She was also married and with children. So, you know, there was a companionship there and an understanding of each other’s difficulties – trying to do some science as well as run a family,” says Visweswariah.

Unlike Seshagiri and Visweswariah who directly joined the department for their PhD, Singh joined the Division of Biological Sciences as an integrated PhD student in 1997 – when Seshagiri and Visweswariah were faculty at MRDG. After trying out different labs across departments in the biological sciences during her lab rotations, Singh decided to join Tatu’s lab in the Department of Biochemistry. It was her interest in host-pathogen interactions, in understanding how disease-causing organisms interact with the organisms they infect, that led her there.

Singh recalls the time she spent in the department and the academic freedom she enjoyed there. “We had the freedom to perform different experiments – some of which our advisors knew, and some that they didn’t. We could work in the lab at any time, night or day,” she says.

In 2002, when Tatu had procured a MALDI-TOF machine (an instrument that is used to analyse different proteins) for the lab, it gave Singh more access to the coveted instrument and the flexibility to use it at any time. “I remember spending a long time, even in the night, chopping proteins into fragments using the enzyme Trypsin and analysing them,” she says. “This wouldn’t have happened if this was a department or institute facility.” Her face lights up when she says that some of the coolest outputs she got using the instrument were past dinner time. She describes how one night, around 9.45 pm, she predicted an unknown protein in Plasmodium to be a chaperone (a class of proteins that serve as quality control to check whether the proteins in the cell get folded into the right shape). “As a graduate student, it was an exciting experience,” Singh says.

“We had a feeling of togetherness, discussed ideas, and knew how to troubleshoot problems in experiments. Most of all, we enjoyed great academic freedom”

She also recalls the magnanimity of students in the department. She narrates how she and a few others in the lab had to collect O+ blood to cultivate Plasmodium for their research. “Every three weeks we would get hold of a person whose blood group was O+, take them to the Health Centre, and collect their blood,” Singh says. “It’s amazing how we drew blood from some people a dozen times, and I now realise we didn’t even take them out for dinner! It was such a selfless thing they did.” She adds that they eventually also became friends with the people in the Health Centre who used to draw blood for them.

However, as is the case with any graduate student, Singh’s PhD was not a smooth sail. She had her own share of struggles. Once working on an important experiment with Plasmodium cultures, she had set the incubator temperature to 37°C, but it failed to work, and the temperature rose to 42°C. “All the cultures I was maintaining died,” she says. After this incident, Singh embarked on a lookout for model systems whose genetics can be easily manipulated for experiments. Eventually, she went on to do her postdoctoral research on another organism called C. elegans, and now studies interactions betweenC. elegans and bacteria.

After her postdoctoral research abroad, personal and professional reasons led Singh to return to India. She had applied for a faculty position at nine institutes in India, and received offers from six including IISc. “IISc is an amazing place, and Bangalore is very open to people who are not Kannadigas. And I liked MRDG for the diversity in terms of the questions they address and the model systems they use,” she says. These factors, and her conversations with Visweswariah, who was by then a faculty at MRDG, influenced her decision to join IISc.

These and many other experiences from the Biochemistry Department shaped Singh, in some ways, to be the scientist she is today. When she joined Tatu’s lab, it was relatively new – she was the third PhD student in the lab. “When I joined the lab, we were still trying to set up a lab. So, I [gained experience in] how to start a new lab,” she says. Seshagiri and Visweswariah also agree that the training in the department came in handy while setting up their own labs. It gave them essential lessons on the “how-tos and how-not-tos” of running a lab. Seshagiri says that his responsibilities in Adiga’s lab, having to procure chemicals and equipment, helped him later on. He adds that the qualities he had imbibed from the PhD training in the department – interpersonal skills, a hardworking nature, and the self-confidence to do things in the face of difficulties – also helped.

From mentee to mentor

Some of the professors at the department, and the Institute, left a lasting impact on the students. “Academically, I grew up among a super-class of professors and teachers,” Seshagiri says. He is all praise for his advisor’s intelligence and commitment to research. “Adiga was a great mentor; very time-conscious and work-conscious,” he says. Visweswariah also describes Adiga as a strict mentor. NR Moudgal and G Padmanaban were two other professors who strongly influenced Seshagiri. Moudgal’s courteous nature, generosity, and incessant efforts to stay connected with the western world and bring Indian molecular reproductive research infrastructure on a par

with the USA, left a deep impression on Seshagiri. “Moudgal is one of the finest reproductive endocrinologists the country has seen,” he says. He still admires how Moudgal “singularly established the primate research facility in IISc, which was one of the first in the country, and is still functional.” Seshagiri also served as the convenor of the facility for about six years.

Padmanaban comes across as a professor who influenced many students. “He was somebody who everybody looked up to,” Visweswariah says. There is a sense of respect and admiration in their voice as they talk about GP (as they call him affectionately). “GP was one person who strongly influenced me indirectly,” Singh says. “He asked fundamental questions which reminded me why I was doing what I was doing.” In addition to his intense commitment to research, Seshagiri also remembers how humble, self-disciplined and humane GP was. “Most of all, GP was a very approachable person, be it for research advice or social events,” he says, remembering the days when they played cricket together.

Singh also describes how her advisor was very critical of his students, and in hindsight, how that helped her think things through before verbalising them. She now tries to apply that to her own research to ensure that there are no gaps. She adds that IISc has this amazing ability to bring that out of certain people – the confidence that they can do it.

In many ways, these alumni have passed on some of the qualities they absorbed as students, from their seniors and professors. Visweswariah says that MRS Rao, who was a postdoctoral fellow when she was a PhD student but a faculty member in the Biochemistry Department when she joined MRDG, was another person she looked up to. Rao went on to chair the department and later became the President of the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre

for Advanced Scientific Research (JNCASR).

Visweswariah herself has been an inspiration for the next generation of scientists, including Singh. “Sandhya has always been a mentor since I came back. She’s the kind of mentor that I can disagree with, and let her know that I disagree with her views,” Singh says.

This nature of paying it forward is essential to build a great legacy. Which is what these alumni have been doing since they came home, giving back to their alma mater while moving ahead in their academic journeys.

Joel P Joseph is a PhD student at the Centre for BioSystems Science and Engineering (BSSE) at IISc