PR Krishnaswamy, alumnus of the Department of Biochemistry, has had a distinguished yet unconventional research career. In the second of this two-part profile, he recounts how he went from academia to industry to the corporate world and back, all the while pursuing his research interests

It was a rainy day in July 1973 when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi arrived to inaugurate the Jaslok Hospital in Mumbai. After her speech, she was taken on a tour of the 20-floor hospital by its Director, the surgeon Dr Shantilal Mehta. With them was PR Krishnaswamy, who had set up the most striking feature of the facility, the pathology laboratory and research space which occupied one-and-a-half floors.

“She was astonished,” says Krishnaswamy. Having been given a free hand by Dr Mehta, he says he had filled the laboratory with the latest equipment and trained clinicians, creating a research facility unique among private hospitals in India at that time.

It was quite a turnaround for Krishnaswamy. After completing his DSc with KV Giri at the Department of Biochemistry at IISc, with many notable publications to his credit, he went abroad to work with Alton Meister at the Tufts University School of Medicine. But when he returned to India in 1963, he did not have a job. He initially worked at the Central Food Technological Research Institute (CFTRI) in Mysore but could not get a permanent appointment despite his research record. Good advice led him to join the Protein Foods Association of India (now the Protein Foods and Nutrition Development Association of India) as its first Director. And now, he was giving the Prime Minister a tour of the research space he had put together at Jaslok Hospital.

He had joined CFTRI initially in an honorary position, and began work on child malnutrition, collaborating with the CSI Holdsworth Memorial Mission Hospital nearby. They found that the nutritional deficiencies in malnourished children rendered their body unable to utilise even the meagre amounts of proteins that were available in their food. They excreted significant amounts of unutilised amino acids in their urine. Among them was the cyclic form of glutamic acid, 5-oxoproline.

They found that the nutritional deficiencies in malnourished children rendered their body unable to utilise even the meagre amounts of proteins that were available in their food.

Krishnaswamy was familiar with glutamic acid, having worked on it at Tufts. Its cyclic form, 5-oxoproline, is not usually found in blood or urine to any great extent, as he found by analysing his own. “But in malnourished children, I found it in their urine in large amounts,” he says. It had always been considered to be a compound without metabolic significance, but Krishnaswamy, in collaborative experiments with a colleague at CFTRI, D Rajagopal Rao, was able to prove otherwise. Their publication on the metabolic significance of 5-oxoproline set the stage for further discoveries and studies on medical applications.

During this period, M Sreenivasaya, his mentor at IISc, came to visit him at CFTRI. “I told him about our oxoproline work,” he says. “The most satisfying moment for me was his extraordinary exhilaration. It was my tribute to his mentoring me in the early part of my career.”

His initial honorary position at CFTRI had led to a CSIR Pool Officers’ fellowship after six months, but it proved to be a dead end. He couldn’t get a permanent position even after three years, and decided to leave. “This was a crisis in my career,” he recalls. Fortunately, through contacts, he soon took up a more challenging assignment, on a national level.

This period, 1966-67, saw a famine in Bihar, and the country experienced a food shortage. The grim situation, says Krishnaswamy, galvanised some of the leading players in the food industry, such as Hindustan Unilever, Amul, Nestle and Brooke Bond, among others, to work together, leading to the formation of the Protein Foods Association of India with the help of USAID [United States Agency for International Development]. The Association offered him the role of Executive Director. “What I had to do was to advise the government, advise the industry, set up programs, work with UNICEF [the United Nations Children’s Fund] and the WHO [World Health Organisation], and other organisations on practical implementation; get everyone interested. This was a job I had to do single-handedly,” he says.

He initiated nationwide surveys that showed that protein and caloric deficiencies were prevalent in the middle class too, and worked on campaigns to raise awareness about these deficiencies. Among these was a 20-minute documentary film, “Your Child’s Plate is His Horoscope,” starring the late actor Smita Patil and made by a team involving actor and author Gerson da Cunha and filmmakers Shyam Benegal and Mrinal Sen. It was produced by the Films Division of the Government of India and shown before movie screenings in all cinema theatres across the country. “The experience of working with all of them on this film was a most memorable one,” says Krishnaswamy.

The Association also facilitated food companies developing products that could ameliorate nutritional deficiencies – such as weaning foods, and wheat flour fortified with lysine, an amino acid – and used existing distribution networks to make these available even in remote areas.

Before joining the Association, Krishnaswamy had informed them that he did not intend to stay beyond three or four years. In the meantime, he had been visiting medical colleges to give occasional lectures to students and interact with faculty. “This contact with the medical profession opened a few doors for me,” he says. This eventually led him to meet Dr Mehta, who offered him the position of the Chief of Laboratories of Pathology and Head of Research at Jaslok Hospital that was then being built. “It was the most premier hospital in the country,” says Krishnaswamy. “Though it was a private institution, it was shaped in the first decade by one of the most outstanding doctors, surgeons, teachers and visionaries in this country – Shantilal Mehta put it together with a lot of idealism.”

A fourth of the beds at Jaslok would serve the poor, free of charge, and another fourth were available at subsidised rates. Jaslok became well-known after Jayaprakash Narayan was admitted for renal failure during the Emergency, and stayed for many months. “By turns we would go and sit with him and talk to him, listen to his stories,” says Krishnaswamy. “JP’s presence made Jaslok a household name in the country. Famous and influential people, including chief ministers, would come for treatment there.”

But Jaslok also earned its reputation through its research efforts. The equipment at Jaslok’s laboratories, recalls Krishnaswamy, included many new technologies such as an electron microscope, spectrophotometers, cold centrifuges and amino acid analysers. One of the studies he undertook during this period was on the pathophysiology of diabetes. Krishnaswamy knew that increased blood sugar levels oxidise and modify the structures of proteins, including haemoglobin, through a process called glycosylation. Working with Dr HB Chandalia (professor of endocrinology at Grant Medical College), he developed a method to estimate the levels of glycosylation of haemoglobin in diabetic patients. This “HbA1c test”, as it came to be known, was a useful method for monitoring diabetes treatment, a novel approach at that time in India. Its introduction at Jaslok was an early innovation, and brought the hospital to the attention of endocrinology researchers and clinicians in the country.

This “HbA1c test”, as it came to be known, was a useful method for monitoring diabetes treatment, a novel approach at that time in India.

Such a research culture was enabled by weekly meetings where clinicians would present interesting cases. “That’s not done even in most corporate hospitals nowadays. People don’t have the time because it’s so practice-oriented,” says Krishnaswamy. Jaslok also ran its own journal which he edited for a while.

(Photo courtesy: PR Krishnaswamy)

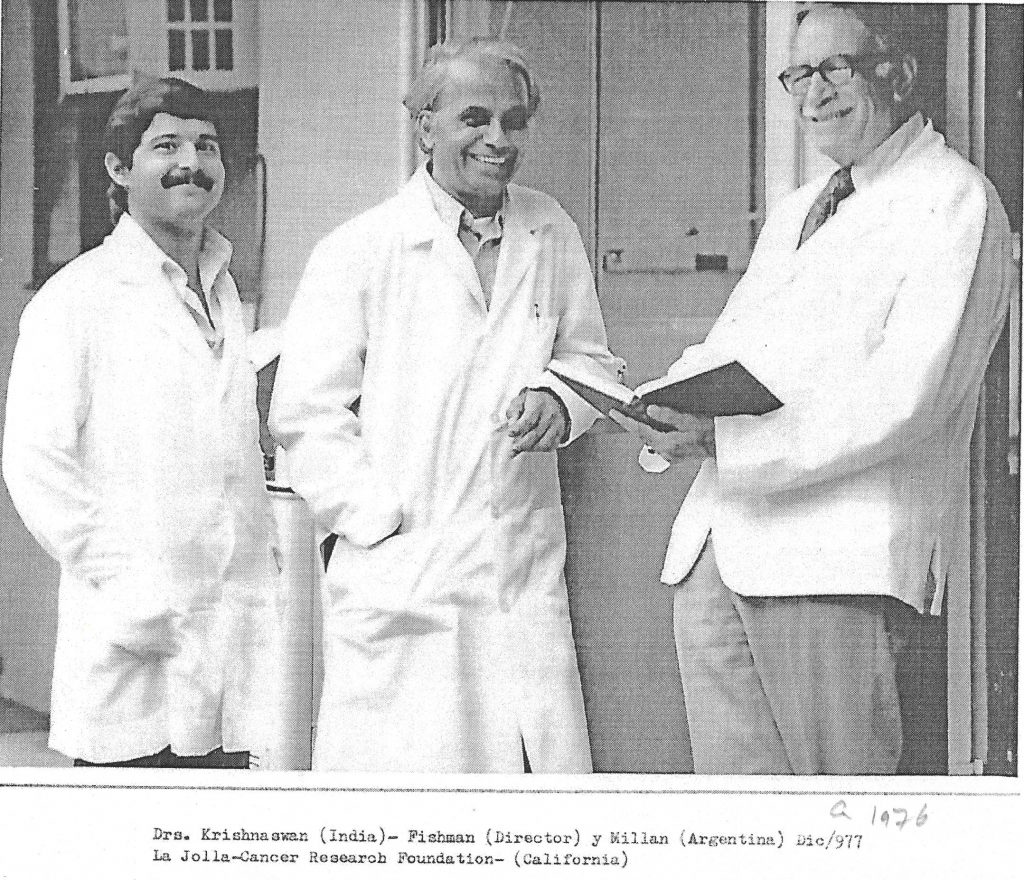

At Jaslok, Krishnaswamy worked on other research problems too. In the late 1970s, he found that seminomas, germ-cell tumours of the testes, express a protein, a membrane enzyme called gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. “I suspected we should look at it in all germ-cell tumours as a marker. That, I couldn’t do in Jaslok fast enough because we don’t get so many cases of that kind of cancer.” So he applied for and obtained an International Cancer Union fellowship to visit the La Jolla Cancer Research Foundation (now the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute) to work on biomarkers for testicular tumours. “It was preliminary work but later on people took it to other levels.”

Then, in 1983, Krishnaswamy had a visitor at Jaslok. “I had thought he had come for a blood test or to have some investigations done. He said, ‘I want to ask you whether you would consider a very senior position in the UB [United Breweries] Group board and as head of research for the whole Group.’ I said, ‘Are you kidding me?’” The man turned out to be a headhunter for the UB Group who had zeroed in on him.

Founder-Director William Fishman (Photo courtesy: PR Krishnaswamy)

Krishnaswamy flatly declined and sent him away with a list of suggested names. But four months later, the recruiter returned, saying that all of the suggested people had pointed him back to Krishnaswamy as the most suitable person. He mulled over it for many months, and eventually met Vijay Mallya in Bangalore. “I was astonished,” says Krishnaswamy of Mallya. “He was about 28 then; I had not met many at his age who were as composed, articulate, effectively communicating, clear in his thoughts and goals, and convincing. I was impressed with what he was made up of,” he says. “My apprehension was whether I could do what was needed and what would be enjoyable for me.”

He had known Vijay’s late father, Vittal Mallya, from his visits to Jaslok. The UB Group had about 30 companies, and Vijay wanted to transform them and expand the Group’s operations. He also wanted to invest in research that could support these goals. “He said liquor is our main business but he wanted to diversify,” says Krishnaswamy. “He wanted to become a technology-oriented, well-diversified group in a changing world, where new technologies were emerging.”

In 1984, after 12 years at Jaslok, Krishnaswamy decided to leave and join Mallya as President of Group Research and Development, on the condition that he would be allowed to engage in research in the rapidly developing field of biotechnology. This, he proposed, was to be done through a standalone not-for-profit foundation which the Group would have to support, but which would eventually generate its own funds. “He readily agreed,” says Krishnaswamy. “But he put one rider. He said, ‘You set up a hospital in my father’s name in Bangalore.’ I said I’ll do it.”

This became the Mallya Hospital. Krishnaswamy also worked as a president of the UB Group, on its supervisory board. In parallel, he recruited people for what was named the Vittal Mallya Scientific Research Foundation (VMSRF). He even set up a separate technical centre which did research on developing and improving the Group’s products, or, as he puts it, their core “spiritual” business. “I didn’t want to mix the science part of the operation with the business-oriented research,” says Krishnaswamy. “I think, for new ideas, the creative thing must be separate but integrated when needed.”

He organised research at VMSRF, with more than two dozen researchers and PhD students, at a time when biotechnology in India was at a nascent stage. One of the achievements of the research efforts at VMSRF was to synthesise recombinant insulin, a project that took four years. “Without any vanity, I can say that it was perhaps the first attempt in the corporate sector to undertake research,” says Krishnaswamy. “Mallya was very proud of it; I wish he had stayed on that track. He gave us every support for basic research and academic excellence.”

Krishnaswamy’s move from Mumbai to Bangalore had meant that his wife, Rukmini, had to leave the SPJ Sadhana School for children with special needs, where she was the Principal. In Mumbai, she taught at various other schools and worked with kids in Dharavi. “I would start my day with preschoolers,” she says, “and end it with teaching postgraduates in developmental psychology.” Having trained in the subject at Harvard, she pursued her calling by starting a school on the CFTRI campus in Mysore, where she developed her methods in inclusive education by having children of faculty and staff learn together. After moving to Bangalore, she became one of the founders of the Spastics Society of Karnataka, and has now spent more than six decades working with children, particularly those with special needs, and training teachers and parents. “We now serve over 4,000 children in all our institutions, mostly in rural areas. We work in district hospitals, community medical centres, various hospitals,” she says.

Krishnaswamy left VMSRF after 12 years, in 1996. But this did not imply retirement. As Director, he headed the Diagnostic Division – the Pathology Laboratories and the imaging facilities – at Manipal Hospital, where he continued to mentor PhD students working on disorders such as thalassaemia, and investigating biochemical changes in renal patients. “I was also an Honorary Director [of the hospital], the only condition of engagement being that I would be free to pursue my research interests, ‘translational’ in nature, on clinical problems.”

Around this time, he started collaborating with P Balaram, the former Director of IISc. “He’s tremendously interested in haemoglobin as a protein molecule,” says Krishnaswamy. More recently, he has also worked with Navakanta Bhat at the Centre for Nano Science and Engineering, and the team behind PathShodh, a start-up that has developed diabetes monitoring devices. In parallel, he has advised students at Sri Devaraj Urs Medical College in Kolar.

“One of the things which added real value to my career,” says Krishnaswamy, looking back over his decades straddling academia, industry, and the corporate world, “is that I dabbled in many things. Not by choice, but I made the most of what I could do. And I gained a lot in terms of my own happiness.”

Read the first part of this interview here.