The Centre for Electronics Design and Technology (CEDT, now the Department of Electronic Systems Engineering) was established in 1975. The initiative for this Indo-Swiss collaboration was taken by Arvind Shah, who recounts the events in this 2014 memoir.

After finishing my studies in Electrical Engineering at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zürich, with a PhD, which I obtained in 1968, it had been my intention to return to India and to found an industry. This was very much what my father had wanted me to do. He had himself always wanted to start a manufacturing plant for radios in India, but had never been able to do that, for lack of capital and technical expertise. He had remained “just” an inventor and a radio merchant. But it was his ambition that his sons should pursue his dream.

My father passed away in 1960. Our whole family was then living in Switzerland, as my mother had Swiss origins. At the time, my elder brother was already married and had five children, so he was hardly thinking of leaving Switzerland. The task of carrying out my father’s dream and implementing an industrial fabrication unit in India became, thus, my own mission.

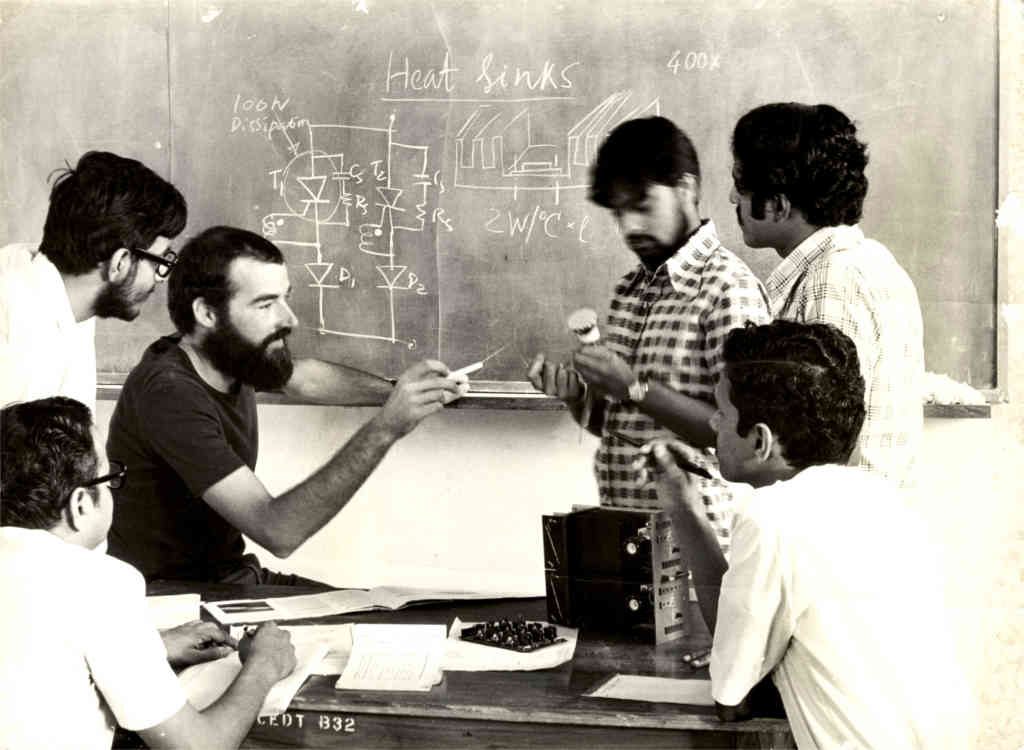

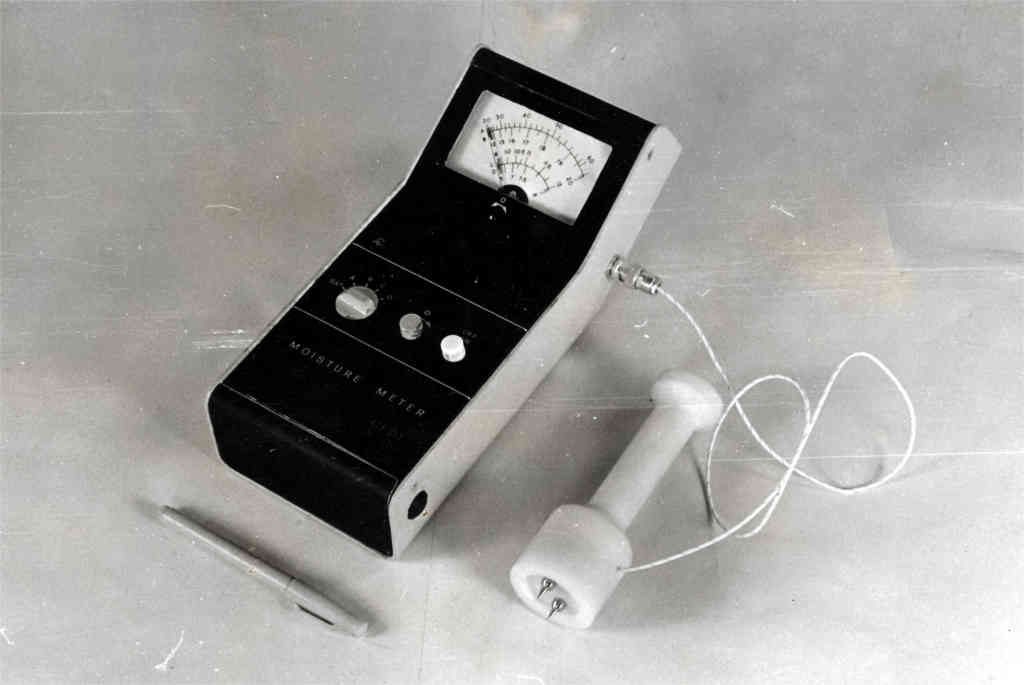

In 1969, one year after my PhD, I travelled to India – to Bombay, Delhi and other places, mainly in the North, and met with many people who were already connected with industries in India. I had drawn up, together with another Indian graduate from ETH Zürich, a short description of the type of manufacturing firm which we wished to start. It was to be called the Yantra Co., and we intended to produce electronic measuring instruments, such as oscilloscopes, impedance metres, etc. During my trip it became very clear to me that the plan my friend and I had drawn up was still very far from being viable, that we would have to solve a number of problems before we could think of starting a factory, and that neither of us had any experience in manufacturing at all. During my trip I also repeatedly heard, from Indian industrialists, the complaint that the engineers which they were able to recruit in India were totally unsuited for work in an industry, as they completely lacked skills in electronic equipment design. The background of these engineers was (so I was told) purely academic and theoretical. This gave me the idea that I myself would be of greater use in contributing to improve the education of electronic engineers in India, rather than in founding my own firm.

I repeatedly heard, from Indian industrialists, the complaint that the engineers which they were able to recruit in India were totally unsuited for work in an industry

1969 was a decisive year for me in many other ways too. At the time, I was employed as lecturer and postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Technical Physics and Department for Industrial Research of ETH Zürich, and was entrusted with the task of setting up training facilities for undergraduate students in Electrical Engineering (EE). The programme I developed for practical training of electrical engineers met with large success; our lab was selected by a majority of the EE students at ETH Zürich for doing their Diploma (Masters) project.

During that period, I met my future wife Brigitte, who was deeply interested in India, and together we started to make plans for our future tasks there. Brigitte was not very convinced of the idea of me setting up a manufacturing unit in India, especially as I had not been able to find a fully reliable partner for this endeavour. (The other Indian graduate from ETH Zürich had shown great interest and even enthusiasm in the beginning, but he had in the meantime found other centres of interest; he was becoming more and more of a “sleeping partner”.)

Based on these factors, I myself took the decision of abandoning my first ambition of founding an industry. Instead of pursuing the industrial road, I decided that I should continue, in India, to do what I best knew how to do, i.e. to train EE students to become useful and competent engineers.

In spring 1970, my wife and I spent a few weeks of holidays in a rather secluded place in northern Italy, a place called Valsesia, from where my maternal grandfather had originally come. It was in this region of hills and forests that I drew up, together with my wife, the idea of a Centre for the Practical Training of Engineers to be implemented somewhere in India. It was a handwritten document of about 20 pages.

We then sent this document to the Department for Technical Cooperation of the Swiss Foreign Ministry, i.e. the Swiss Government agency responsible for development projects (now called the SDC, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation). It was a tremendous stroke of luck that this document fell into the hands of Henri-Philippe Cart, an economist responsible at the SDC agency for university projects and somebody with a very open mind.

Dr Cart wrote back to me that he very much liked the ideas that I had jotted down in my handwritten notes and he invited me to work together with SDC to turn these ideas into an actual full-fledged project for the Indo-Swiss development programme. Dr Cart also convinced me that “my” project would best fit into one of the existing IITs in India. It was to be my task to find an IIT which would take up “my” project and agree to implement it.

In October 1970, I travelled with my wife to India. We met my relatives in Bombay, and I showed my wife many places in India. At the same time I strived to make contacts with several IITs and with the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bangalore. IISc had been recommended to me by Thomas Kailath, an Indian professor whose acquaintance I had made in the summer of 1970 when visiting Stanford University. I had shown Prof Kailath my “handwritten document of about 20 pages” and he had told me that he knew one place where such a centre (as I dreamt of) would be welcome: That place would be IISc in Bangalore. He had given me an introduction to the Director of IISc, who, at the time, was Prof Satish Dhawan.

Bangalore was the last stop in our trip; I had already met with the persons responsible for Electrical Engineering at the IITs of Bombay and Kanpur, but had only obtained very lukewarm reactions. Satish Dhawan accorded me, at very short notice, a few hours of his time for an in-depth discussion with him, and during that discussion took the decision of implementing “my” project at IISc. He entrusted Prof BS Ramakrishna, Head of the Electrical Communication Engineering (ECE) department with doing all the groundwork on the Indian side. That was truly the birth of the CEDT.

Satish Dhawan took the decision of implementing “my” project at IISc

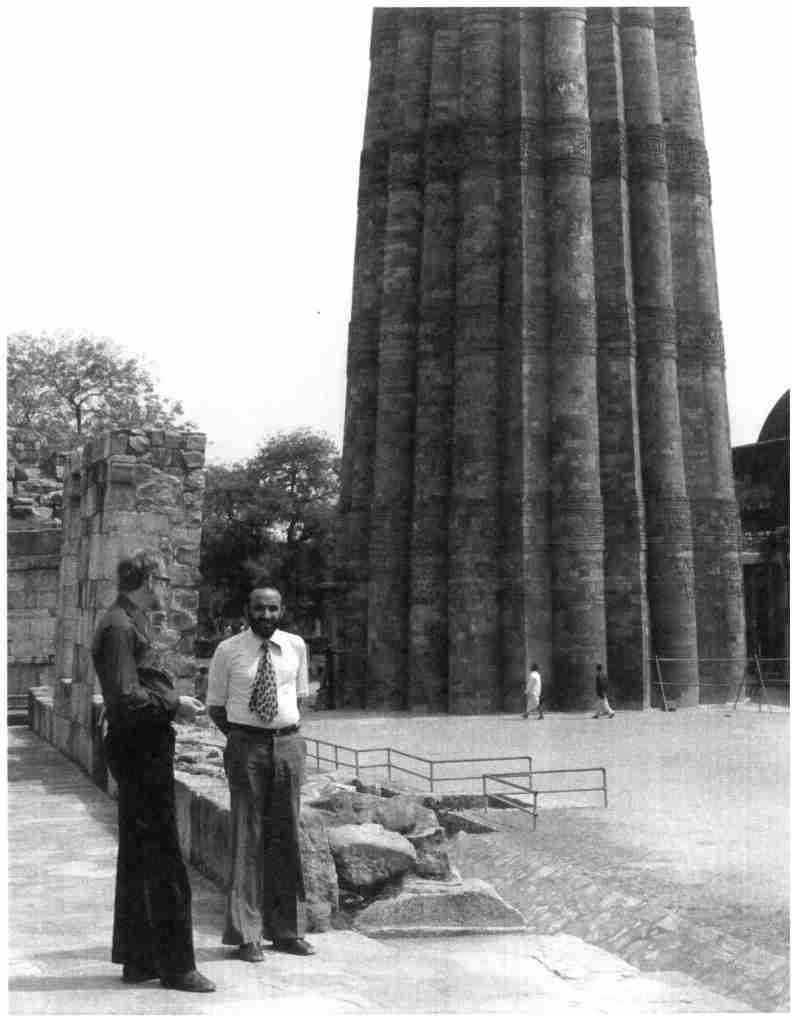

There followed five long years of negotiations, evaluations and budget-hunting, until in May 1975, I could finally travel to Bangalore with my wife and our two small daughters, Devika and Chandrika (aged 3 and 2), to implement the Centre for Electronics Design and Technology, as a part of the Indian Institute of Science. Whereas I myself had pushed the files with the Swiss government authorities and convinced committees and critics within Switzerland of the viability of the project, it was Prof BS Sonde who had done all the spadework on the Indian side and had made sure that IISc could administratively integrate the CEDT. Both of us had met with government officials in India and Switzerland.

The Electronics Commission of the Government of India played an essential role in financing the CEDT on the Indian side. Again I was lucky: Once, I happened to travel in the same plane as Prof MGK Menon, the Chairman of the Electronics Commission. I had the occasion to talk to him about the future CEDT. He gave useful suggestions and from then on took a special interest in this project. It even turned out that the nephew of my friend with whom I had originally wanted to found a manufacturing company in India was working with the Electronics Commission at the time. He too was very helpful. And Henri-Philippe Cart, the first supporter of the CEDT, became the coordinator of all Swiss development projects in India. He reported back to the Swiss government that they better hurry up with taking a positive decision of implementing the CEDT, because the Indian government was counting on Swiss support here. Without all these people taking a personal interest in implementing the CEDT, the project would have got stuck in the meanders of both the Swiss and the Indian administrations.

From May 1975 onwards, I spent four years in Bangalore bringing up the CEDT, together with Prof Sonde, to a certain level of success and recognition. It was again a stroke of luck that Prof Sonde was my partner in this, because the two of us made a good team: We had complementary outlooks and talents, and had often to argue for hours and hours until we came to a consensus – but it was precisely the fact that we represented different cultures and visions which turned the CEDT into a success story.

But the first months at IISc were quite a shock for me. I had left India in 1954, at the age of 14, and returned since then only for short visits to my relatives in Mumbai. I had really no idea of daily life and of work routines in India.

It was precisely the fact that we represented different cultures and visions which turned the CEDT into a success story

When we arrived in Bangalore, it seemed to me that many insurmountable problems were facing me. The future CEDT had been allotted some space within the building of the ECE department. But this space, in May 1975, consisted only of a few empty rooms; the furniture for our future laboratories and offices was still in the process of being fabricated. There was no equipment at all; some of it was still to be bought in India, another part of it, which had been ordered outside India, based on funds from the Swiss government, was held up by customs in Chennai. There was no staff as yet, except for a secretary; two future faculty members, Dr Jamadagni and Dr Bhat, were still in Switzerland for their “training period”; the technical staff was yet to be engaged. Meanwhile, the first batch of students were scheduled to start their Diploma programme within a few months, but I just could not see how we could get ready within such a short time.

During the first months in Bangalore I remember having, almost every day, long discussions and even quarrels with Prof Sonde. I do not remember what these quarrels were about, but I do remember that they had something to do with our different backgrounds. And I suppose we were both extremely nervous about how the new Centre would fare. With time, the situation would completely change – with a lot of goodwill from each of us, we would learn to communicate effectively and form a good team.

But right in the beginning it seemed to me that everything was going wrong. I was just sitting there in my empty office within the CEDT and waiting for things to happen. And all that I got was news of some new problems and further unexpected delays.

After the first two months, I was totally disappointed and discouraged. I remember telling my wife, who had, in the meantime, found an interesting task to accomplish at the section for mentally retarded children of Sophia’s High School in Bangalore: “Look, you have found something useful and interesting to do here in Bangalore, but for me, my stay here is just a pure waste of time – if it was up to only me, we could return to Switzerland tomorrow.”

Luckily my wife did not at all want to return to Switzerland – and so we stayed on, for totally four years: four years that became one of the most productive and interesting periods in my whole professional career. Together with Prof Sonde and with the whole team of Indian and Swiss staff we were able to setup a Centre that was quite unique and met with tremendous success.

A lot of our time, in the early period, was spent in getting the laboratory ready. I remember traveling to Chennai together with Prof Sonde, in order to discuss with Customs officials there and get our equipment through Customs in record time. I remember how many evenings both Prof Sonde and I remained at the CEDT to handle all the administrative tasks. I remember going with him to the carpenters, in an attempt to hasten up the completion of our furniture. I remember sitting, together with Prof Sonde, in interviews and committee meetings, so as to engage the necessary staff within the short time remaining before the students were to come.

But when our first batch of 10 students arrived for their one-year Diploma programme in August 1975, we were indeed ready to receive them and to put them to work in our labs, which were just coming into shape. The 10 first students were all very dedicated and hardworking. We had set as a precondition that they should have a few years of professional experience and that their present employers should send them to the CEDT on deputation. This system worked well for engineers from government laboratories and large firms, but it did not work at all for engineers from small-scale industries. After all, which small-scale industry can afford to send away a capable young engineer, for a full year of further training, without replacing him? Therefore, in the beginning of CEDT, we had great difficulty in finding enough candidates to fill the twenty seats we had for our Diploma course.

The CEDT course was several years later modified to become a Masters programme and to accept young engineers directly from university, without professional experience and without industrial sponsorship. From then on, there was no difficulty anymore in finding enough students and the CEDT students definitely had more intellectual brilliance. But I have always felt that in the process of changing the CEDT course and the conditions for joining it, we also lost a lot. We did not anymore have a majority of very practical down-to-earth engineers studying at CEDT, a bunch of engineers whose main goal was to start their own industry. CEDT has, thus, become much more like any other department of IISc.

This is, indeed, an eternal dilemma for CEDT: Either be true to its own originality and then continuously run into administrative and other difficulties with the rest of IISc, or adapt to what the other departments are like, become more academic, and in the process lose track of its mission.

In the early years we had a very hard time with the rest of IISc, who did not understand us at all. But we were, on the other hand, well esteemed by industry, and did an almost heroic job of introducing new concepts in technical education. Most of the other professors at IISc just barely tolerated us, feeling that we were lowering the academic standards of IISc. In the meantime, CEDT has become well-integrated within IISc. But maybe is it now too integrated, too adapted to the more academic education given by IISc in general?

Also read: An interview with BS Sonde on the founding of CEDT