What old brochures of the event tell us about its purpose, and about how IISc saw itself

The Indian Science Congress (ISC), an annual gathering of scientists, was begun in 1914 by two British chemists, JL Simonsen and PS MacMahon, who wanted to model it on the British Association for the Advancement of Science. In its early days, the ISC served as a platform for researchers across India to meet and communicate their work, and also to reflect on the growth of science in the country. The documents relating to these gatherings, therefore, serve as a mirror for the kind of research that was done at the time and also the role that was seen for institutes such as IISc.

Bangalore has been host to the ISC eight times, and brochures for three of those events – 1917, 1924 and 1951 – can be found, along with that of the 1928 event held in Madras, in the IISc archives. These serve as a window into how the Institute saw itself and its achievements in those times, snapshots of how the Institute presented itself to researchers from around the country and abroad.

1917

Sir Alfred G Bourne, the Director of IISc from 1915 to 1921, was the president of the 1917 ISC held in Bangalore. Bourne was a zoologist and botanist who first came to India as Professor of Biology at Presidency College, Madras.

In his presidential speech at the 1917 Congress, Bourne reflected on what the vision of ISC was at the time. One of the aims of the British Association was the “removal of any disadvantages of a public kind which impede” scientific progress. Bourne felt that this was now largely redundant, even in India, since the government and the public had greater appreciation of science and its importance. But research requires funds – at the time, the money spent annually on scientific work in British India, according to Bourne, was Rs 70 to 80 lakh, an amount that was supplemented by some of the “native states” such as Mysore. “Private sources,” he said, “have contributed but a lamentably small extent,” with rare exceptions like the Tatas. He contrasted this with the situation in England where the share of research funding from private sources was much more.

Another aim of the British Association was “to give a stronger impulse and a more systematic direction to scientific inquiry”. “It seems doubtful whether much will be done in this respect,” said Bourne of the ISC, “if the programme continues to be limited to an address from the President, a few public lectures; and for the rest, meetings in small sections for the reading of papers some of which, I gather from past proceedings, have been mere preliminary notes, while others, although valuable contributions to science, are of immediate interest to very few.”

He noted that because of increasing specialisation, researchers in one field must make special efforts to understand and keep up with research in other fields, and that this must be the main purpose of the ISC. “Should not some attempt be made throughout the meeting,” he asked, “to deal with subjects intelligible to all students of science alike?” He said that “the isolation hitherto experienced by many scientific workers in India has been one of the chief reasons of the comparatively disappointing results”.

Should not some attempt be made throughout the meeting,” Bourne asked, “to deal with subjects intelligible to all students of science alike?

Bourne also reflected on the nature of research and identified three classes of research: “that carried on with the single purpose of ascertaining the truth in regard to the causes of things, that which has for its immediate object a specific utilitarian purpose but still without any expectation whatever of a pecuniarily remunerative result, and research with the avowed object of making money out of it sooner or later.” “The first class alone,” he went on to state,“is research in pure science; second and third are applied science.”

He noted that this classification of research into pure and applied can only refer to current and not past research – these distinctions are erased by time. Bourne then spent a good part of his speech in reflecting on the nature of a word he felt is used too loosely. “Research,” Bourne felt, “is now alluded to as a perfectly simple operation. One even hears of men being ‘taught to research’; newspapers speak of it in the lightest manner, whereas, in even my student days, it was spoken of with almost bated breath as indicating something to which only the best of us could look forward, something which few of us were ever likely to carry on with any hope of success.”

He argued that applications will unexpectedly emerge from pure science research, stimulating further research. “What utilitarian research,” he asked, “would have discovered the fundamental facts in regard to electricity or have led to the framing of the atomic theory?”

But this was the period of the First World War, which prompted Bourne to concede that the Institute should do work of an applied nature to help industry. He feared that “pure science may be almost submerged for a time by a wave of utilitarianism” and asked his audience to reflect upon these matters, saying “each must follow the dictates of his own conscience”.

1924

Bourne’s immediate successor was a chemist, Sir MO Forster, who was Director of the Institute from 1922 to 1933. Forster’s essay about IISc in the handbook for the 1924 ISC listed achievements of the Institute which were all of a strikingly applied nature. Forster went into some detail in describing what he saw as important contributions to industry that had resulted from research at the Institute. He recounted how the extraction of oil from sandalwood used to take place almost exclusively in German factories. But as a result of work at IISc, sandalwood-oil factories were established in the region. “Incidentally,” he noted, “the experience gained has led to marked improvement in the general methods of distilling essential oils as practised throughout the Indian peninsula.”

Forster listed other contributions too, in places far away from Bangalore. For instance, IISc researchers advised the planning of civic works in Jamshedpur, working on the sewage-treatment and water supply in that city. Further, “a well-equipped laboratory for the necessary bacteriological and chemical work is conducted by former students of the Institute, whilst other former students are engaged in the scientific control of waterworks construction and operation at Delhi and at Shanghai.” He also noted that many of the former students of the Department of Electrical Technology “are now to be found in active control of the numerous hydro-electric and other power-generating schemes dispersed throughout the peninsula.”

Forster’s essay about IISc in the handbook for the 1924 ISC listed achievements of the Institute which were all of a strikingly applied nature

Four years later, during the 1928 ISC held in Madras, Forster reflected on a more intangible contribution from IISc. “In one sense,” wrote Forster, “the task of building character, of inculcating clearness of thought, habits of industry, perseverance in the face of disappointment and precision of craftsmanship, is the most important one assumed by the Institute, which has now distributed throughout the country a substantial body of men trained in the art of making and appreciating knowledge and in the technique of solving a problem.”

1951

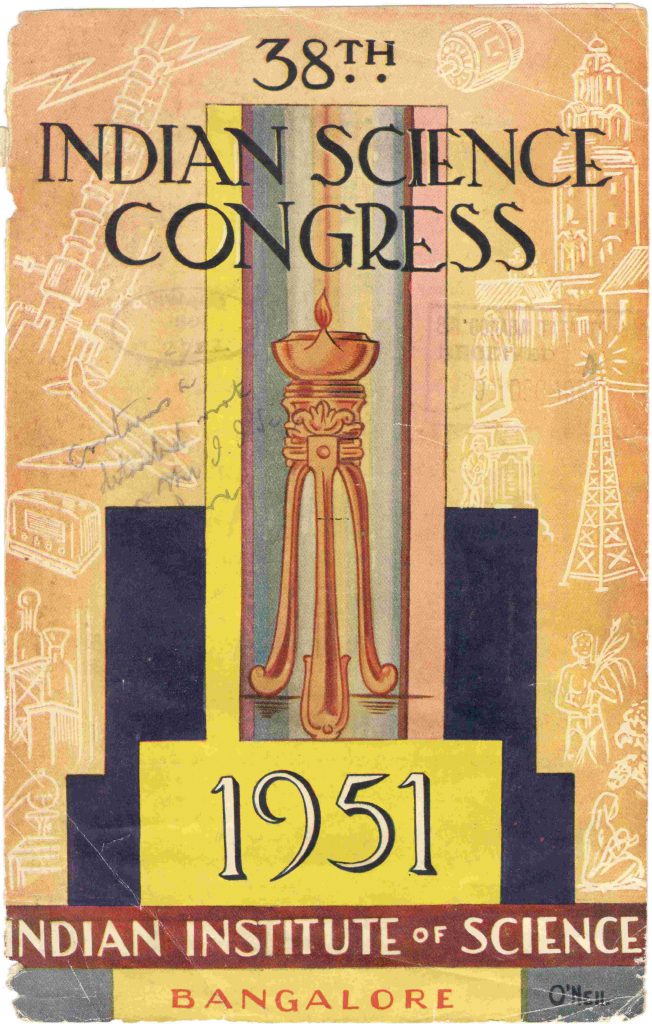

The push for applied research to serve the needs of the war would again be felt during and after the Second World War. There is a change of tone, and a much more strident push for industrialisation visible in the brochure for the 38th ISC held at IISc in 1951 with Homi Bhabha as the President Elect.

As the war drew to a close, a four-year programme of expansion was “inaugurated by the tireless efforts of Sir Jnan Chandra Ghosh, the then Director,” according to the brochure. As part of this programme, the Departments of Metallurgy and Internal Combustion Engineering were founded in the Institute in 1945. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru visited IISc in December 1948 and, among other things, laid the foundation stone for the Department of Electrical Communication Engineering.

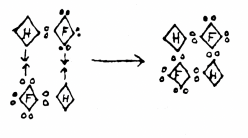

Ghosh was succeeded as Director in 1949 by MS Thacker. At the time, IISc conferred diplomas, associateships and fellowships – not degrees as we know them today. The diplomas (known as certificates of proficiency before July 1946) were for students who completed coursework, associateships were for those who wrote a thesis, and fellowships were awarded to associates who had spent at least five years resulting in “original and valuable research work”. The brochure also gives us numbers. By 1951, IISc had conferred a total of 7 fellowships, 6 honorary fellowships, 252 associateships and 705 certificates/ diplomas. And we learn that “a nominal tuition fee of Rs 12 per month, payable in three instalments per year at Rs 48 per term, is charged to students admitted to post-graduate courses of instruction. No fee is levied for research.” Many important journals were published in European languages other than English during those years.

Accordingly, there were French and German language classes conducted for students in the Institute, “supplemented by practice of phonetics by means of a Magnetic Wire Recorder and Linguaphone”. Technical reports and articles from foreign journals in other languages were translated, and these translations were also distributed all over the country “at prescribed charges”.

Incidentally, the first Pan-Indian-Ocean Science Congress was also held in 1951, concurrently with the ISC. This arose from a proposal by the Australian Council of National Research to hold a gathering of scientists from countries around the Indian Ocean to address problems of mutual interest. Jawaharlal Nehru inaugurated it “in a colorful ceremony attended by some 30 delegates from Australia, New Zealand, Burma, Malaya, Ceylon, Madagascar, the Netherlands and Portugal” and a few from the UK and France too.

In the decades that have followed, as in Bourne’s time, the ISC has not fulfilled Bourne’s aim of giving “a stronger impulse and a more systematic direction to scientific inquiry” in the country

In the decades that have followed, as in Bourne’s time, the ISC has not fulfilled Bourne’s aim of giving “a stronger impulse and a more systematic direction to scientific inquiry” in the country. About a century after Bourne’s speech, another Director of IISc would lament the sorry state of the annual event. “Curiously, few practising scientists of note consider the Congress as an important event,” wrote P Balaram in an editorial in Current Science in 2012. “Pomp and ceremony take precedence over substance.” Over the years, the ISC, he felt, “has been reduced to an occasion where the inaugural session appears to be the raison de etre for the meeting”, and ceremonial speeches, including by Nobel laureates, ensure “that the Congress always acquires a degree of respectability rarely supported by the scientific program.”

Bourne had felt that the ISC was not the venue for presenting highly specialised papers that would be unintelligible to researchers in other felds. He wanted the review of work in different felds, presented by the presidents of the different sections of the ISC, to not be held in parallel, so that they could be attended by interested researchers from all fields – a suggestion that remains relevant today. “But here again the object would be more fully attained,” said Bourne, “were something arranged other than that the agriculturalists should shut themselves up in one room, the chemists in another, while the devotees of Natural Science segregate themselves in various ways and pay very scant attention even to one another…Should not such meetings as this be almost entirely devoted to the bringing together all the time of all the scientists present?”