Organic photovoltaic cells made at IISc were tested in the harsh environs of the world’s southernmost continent

“Things were not going well, but he [Monto Mani, Associate Professor, Centre for Sustainable Technologies] did not let go. He went around arranging for the packaging, got me out of bed at 10 pm, and got me and my students to the lab to test the cell and [other] settings” exclaims Praveen C Ramamurthy, Associate Professor at the Department of Materials Engineering, about his colleague’s tenacity in ensuring that the Organic Photovoltaic Cells (OPVs) they developed at IISc made a successful trip to the South Pole, where they were tested.

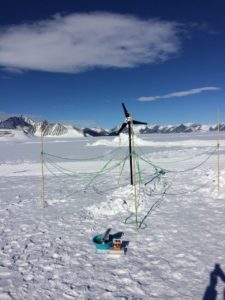

The OPVs developed at IISc were sent to Antarctica as part of the International Antarctica Expedition (IAE) 2017 organised by ‘2041’, an organisation founded and led by polar explorer and sustainability enthusiast, Robert Swan. The cells were carried to the Union Base camp, 80° South and tested by Charulata Somal, an IAS officer and Chief Executive Officer of Kodagu Zilla Panchayat, Karnataka, also a passionate advocate of environment issues and climate change. “Since our expedition was focused on renewable energy, technology from NASA and other companies was being tested. I wanted to [carry] some Indian technology too,” says Somal, who got in touch with IISc to enquire about the possibility of testing a device from here in the extreme environs of Antarctica.

The OPVs developed at IISc, were sent to Antarctica as part of the International Antarctica Expedition (IAE) 2017 organised by ‘2041’

Somal’s offer enticed both Ramamurthy and Mani. They had a device in the works, which they wanted tested in demanding environmental conditions, but preparing it for the harsh environs of Antarctica was going to be a challenge. With less than a week to go before Somal’s expedition, Ramamurthy and Mani got to work.

Construction of the Cells

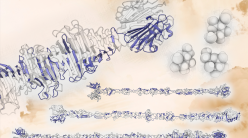

OPVs use an organic polymer to absorb light and convert it into electricity. These cells require almost 1,000 times less energy for manufacturing than silicon-based solar cells, are lighter, more pliable and work well in regions with diffused sunlight.

The OPVs carried to Antarctica from IISc were designed, synthesised and fabricated at Ramamurthy’s lab. Their cells, now in the fourth generation of development, have a novel architecture that facilitates maximal light absorption and current passage, making them function more efficiently. According to Varun Adiga, a student involved in fabrication of the cell, “[the] making of the device was not as challenging as optimising each layer of the cell to ensure that [all] the contacts were in place.”

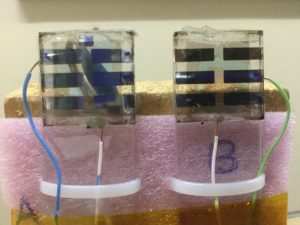

But before the cells could be carried to and tested in Antarctica, they had to be first tested in the lab, which was done by Mani’s team. Several cells cracked. What proved to be the Achilles’ heel was the encapsulation step: a process that provides protection to the cell and enables ease of data recording. This step requires sandwiching the cells between a layer of glass and ensuring that the contacts, electrodes and sensors are all held in place, a challenge that Mani took head on.

When a standard cell is tested in the lab, all contacts are usually fastened using crocodile clips or pogo pins. But Mani and his team knew that clips would not survive Antarctica! Therefore, the team decided to provide a second layer of protection. “We got some really flexible silicon adhesives to press the whole cell between two glasses and use that pressure to hold the electrodes in place” explains Mani. The cells were then mounted on a wooden block and a simple ice-cream bag (a bag to keep instrumentation safe from low temperatures) acted as a portable mini-weather station. The station included a data logger to measure voltage, current, ambient temperature and humidity. Recounting the many methods that the team looked for to prevent the instruments from freezing dead, Mani says, “We did look at many ideas to get the instruments to function at sub-zero temperatures, including a heated box powered by a portable battery bank, but these were getting too complicated and heavy. Something simpler [like the ice-cream bag] was required.”

“[The] making of the device was not as challenging as optimising each layer of the cell to ensure that [all] the contacts were in place.”

The cells, though made to withstand -20°C, were tested at room temperature in the lab, where they logged an operational efficiency of 6-7%, a good number for OPVs. Recalling her experience of testing the cells before they were sent to Antarctica, Khadija Kanwal Khanum, a postdoctoral fellow in Ramamurthy’s lab, says, “We [she and Mani] were both testing the device and had to hold the cells in our hands without disturbing it for about a minute. We have many setups in lab, but this experiment was one of a kind.”

Expedition to Antarctica

Once the device was ready, Mani flew to Jaipur where he handed over the experimental setup to Somal; he also explained to her about how to operate the two cells.

On reaching Antarctica, Somal found that both cells worked, much to her delight. She was able to record data for two hours; she made all the measurements and also took down detailed notes of sunlight conditions. The main objective of the exercise had been accomplished.

After experiments in Antarctica, the cells however went on their own little unexpected expedition!

After experiments in Antarctica, the cells however went on their own little unexpected expedition! On the return journey, the bag carrying the cells was misplaced by the airline. Much to everyone’s relief, it was eventually traced and brought home safely after a month’s travel through many continents.

Performance and future

Back at IISc, Mani and Ramamurthy have now been able to analyse the data from the cells. However, they had to forego data from one of the cells which was corrupted because of mishandling. The cell that survived the harsh conditions of the South Pole recorded an efficiency of 2%. Ramamurthy attributes the low efficiency to temperature cycling, but is pleasantly surprised that the cells turned out to be “robust even after the harsh exposure and the bumpy ride.”

One of the findings of the analysis is counterintuitive. “The efficiency is actually going up with decrease in temperature,” remarks Mani on the data obtained from one of the cells. But he is glad that the cells survived the test of extreme conditions, which is precisely the application they were designed for.

Mani explains why OPVs hold much promise for the future – they require significantly less energy than the commercial silicon counterparts, making them an environmentally friendly alternative better suited to low temperature and low light conditions. However, he adds that issues of stability and performance still remain.

From an explorer’s perspective, Somal feels that the cells have a lot of potential and are a good solution to “keep warm in extreme conditions, especially during white outs, high winds, [and in regions of] indirect solar radiation.”

Anjula Gurtoo, Associate Professor, Department of Management Studies, not involved in the study, says, “The climate change impacts of Antarctic explorations are immense as they use conventional energy for heating, radio [and] lighting. These cells can change that and slow down the use of conventional energy in small consumption areas like [various sensors], radio and lighting.” The research team agrees with her and believes that niche applications stand to gain most from this technology.

Ramamurthy and Mani have now been invited by the “2041” team to test different applications of the same technology at the South Pole by end of this year. What started as a fun exploratory experiment has now opened up a serious research avenue with exciting possibilities.

Ramamurthy (standing second from left) and Mani (standing third from left) with their happy team and OPV cells (Photo: Sudhi Oberoi)

Ramamurthy (standing second from left) and Mani (standing third from left) with their happy team and OPV cells (Photo: Sudhi Oberoi)

Watch Robert Swan’s testimony on OPVs:

1 thought on “This Renewable Energy Tech Travelled All the Way From IISc to Antarctica”

This Renewable Energy Tech Travelled All the Way From IISc to Antarctica – SuDesi

(9 November 2017 - 4:50 pm)[…] Read more… […]

Comments are closed.