Beauty and bias in perceiving art

“I feel like we are nearing the end of times. We humans are losing faith in ourselves.”

Hayao Miyazaki, the Japanese animator and co-founder of the renowned production house Studio Ghibli, uttered these words in 2016 after seeing an AI-generated animation film for the first time. Nine years later, this quote has resurfaced and gone viral.

It started with a single tweet. Someone posted their family photo recreated by OpenAI’s ChatGPT in Studio Ghibli’s distinct style, calling it an “alpha move.” Millions followed, and soon the internet became populated with images of bright, wide-eyed, and innocent-looking people that are so characteristic of Studio Ghibli movies.

The “Ghiblification” trend brought a lot of attention to the rise of AI-generated art, which has existed for over a decade in some primitive form or another. What started in 1973 – with the computer program AARON that could create abstract art – has today devolved into generative adversarial networks, diffusion models, and transformer architectures generating art based on the visual data that they are trained on. In fact, in 2018, a portrait “created” by an algorithm based on 15,000 14th-20th century paintings of people, sold for nearly half a million dollars – the first AI-generated art piece auctioned at such a high sum. Today, several AI platforms, such as OpenAI’s DALL-E, Google DeepMind’s Imagen, and Midjourney, can churn out art mimicking famous artists in a matter of minutes.

Debates rage about how AI art appears “soulless”, with campaigns such as #SayNoToAIArt

While AI art is becoming more mainstream, a growing section of people shares Miyazaki’s antipathy towards it. In an essay in The New Yorker, author Ted Chiang argues that art is about making a series of choices which AI can never replicate, while others like award-winning artist and writer Molly Crabapple are calling upon “team human” to “value the work of real people”. In online forums, too, debates rage about how AI art appears “soulless”, with campaigns such as #SayNoToAIArt.

“My problem with AI art is that it automates something that never needed any automation,” says Komal Shendge, a Bangalore-based digital artist who goes by Kay. “It is made to replace something that was never a burden on humans.”

Anisha Kotibhaskar, a Pune-based artist, for whom art represents a spiritual outlet, says, “When I create a piece, I am telling a story – of my turmoil, emotions, good or bad experiences. Where is the story in pooling a few ideas from here and there and generating ‘art’ as AI does?”

Whether AI-generated art can ever replicate human-made art is a rising debate, sparking deeper questions about the definition of art and what makes it beautiful.

Drawn to beauty

How do we perceive beauty in art?

For some, it is about vibrant colours or striking compositions; for others, it is the hidden symbolism, emotional undertones, or the story behind the brushstrokes. “The painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus really speaks to me. I even have it as my wallpaper,” shares Niranjan Rajesh, a research assistant at the Vision Lab, Centre for Neuroscience, IISc. The 16th-century piece – based on the famous Greek myth of Icarus, who flew too close to the Sun and fell into the sea – shows Icarus’s flailing legs above the waters in a corner of the painting, while the focal point is a village scene with a farmer and a shepherd, seemingly oblivious to Icarus’s plight. “What resonated with me is not the colours or the myth, but the message that life goes on for others, even when we are deep in pain, as Icarus was; humans are rarely in the spotlight as we imagine ourselves to be in,” says Niranjan.

To understand how our brains perceive art, let us turn to neuroaesthetics, a field of cognitive neuroscience investigating the neural basis of aesthetic experiences. “One of the frameworks to understand aesthetic encounters is called the aesthetic triad,” explains Anjan Chatterjee, Professor and Director of the Penn Centre for Neuroaesthetics, University of Pennsylvania. “The first component has to do with the sensory qualities, which help the brain perceive the image.”

Things that are perceived easily by the brain tend to be perceived as aesthetically pleasing

In theory, Niranjan explains, the “best” kind of image would convey the most information with the least cognitive effort. According to a theory called “processing fluency”, things that are perceived easily by the brain tend to be perceived as aesthetically pleasing.

He explains with an example. “When we think of apples, the most standard-looking apple is going to be the best representation of all apples. This property is called prototypicality, and the more prototypical things are, the more easily they are processed by the brain,” he says. Symmetry also enhances fluency. Because a symmetric object contains duplicated elements, according to the processing fluency theory, the brain can process it more easily, making the object look more pleasing.

Yet, the processing fluency theory cannot account for why people like abstract art, which does not have easily perceptible information. Context, meaning, and even the viewer’s expertise and training influence aesthetic valuations. “The second component of the aesthetic triad – meaning and semantics – is where we find that the viewers’ individual differences matter: education, cultural background, the point in history you are living in, and so on,” explains Anjan.

Even social context can influence the aesthetic evaluation of art. “My current favourite artist is my daughter,” says faculty member SP Arun, who leads the vision lab at the Centre for Neuroscience, IISc. “But of course it’s because I have a personal connection to her,” he reasons, emphasising the role of personal relationships in aesthetic evaluation.

The psychologists who proposed the processing fluency theory conducted an interesting experiment to test the role of context. They showed volunteers artworks accompanied by accurate descriptions, ambiguous descriptions, or no descriptions at all. They collected participants’ ratings of the art and measured their subtle facial muscle activity. They found that the zygomaticus – the “smiling” muscle – was most activated when participants were viewing paintings with accurate descriptions. These paintings also received higher ratings, suggesting that knowing the context of the artwork increases processing fluency and enhances aesthetic experience. Even labelling artworks as having been displayed in museums improves people’s judgments about their beauty.

“The third component of the aesthetic triad involves emotions that are evoked by sensory cues,” says Anjan. “If we’re talking about beauty, it’s typically pleasure, though art can have nuanced emotions as well.”

Natural rewards that satisfy innate human needs like food, water, or a mate, activate reward circuitries in our brain that make them pleasurable. The same reward circuits are also activated while viewing art, suggesting that the brain’s reward system has been co-opted by things like art, which represent social needs.

Emotion reflected in the artwork is “felt” by observers

“When you look at a face which has some emotion on it, you can’t help but know what that emotion is. There is a level of automaticity to that,” says Arun. This mirroring effect was first observed in the mirror neurons of macaques – scientists found that the same neurons in the primate’s premotor cortex fire whether an individual is performing an action or observing another individual performing the same action. Similarly, empathetic responses to artwork have also been reported, where the emotion reflected in the artwork is “felt” by observers through the same underlying emotional circuitry.

Colour also elicits strong emotions. “Colour gives art meaning, links it to our real-world experience, creates depth, and elicits emotion,” says Anna Franklin, Professor of Visual Perception and Cognition at the University of Sussex, UK. “According to the ecological valence theory, our colour preferences are determined by what objects we associate with colours and how much we like them.” For example, she explains, we generally like blue since it is associated with pleasant things like clear sky and clean water, whereas we generally dislike dark yellow-green since it is associated with unpleasant things like biological waste and mould.

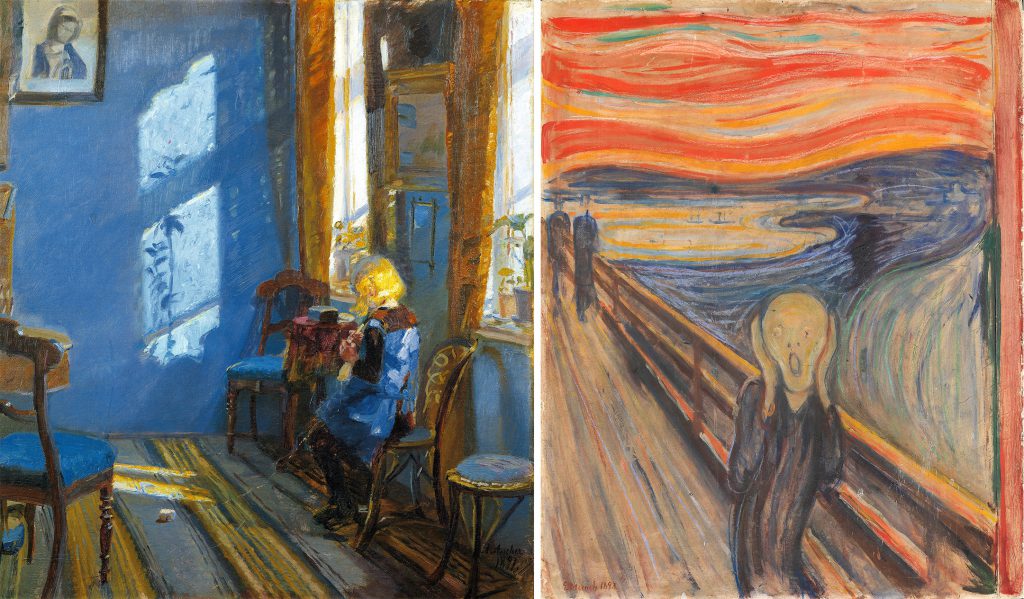

Ultimately, when we look at a piece of art, a lot of processing occurs in our brains. Studies show that regions involved in processing visual features and those encoding contextual information interact within 200-300 milliseconds of viewing an artwork. In cases of dynamic artworks, such as van Gogh’s The Starry Night, the area of the visual cortex that processes motion also lights up. The “aesthetic triad” – ease of perception through fluent features, context and meaning, and emotions – helps explain that our perception of beauty in art emerges from the neural interplay between all these various processes.

Bias colours opinion

How is beauty – or the lack of it – perceived when we view AI art?

In a 2018 study published in the Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, researchers asked participants to classify artworks as human-made or computer-generated and then rate their aesthetic value. The participants rated artworks identified as AI-generated as less pleasing, revealing a clear negative bias. The study also showed that this negative rating was not due to specific visual statistical features, but a cognitive bias against the creative capacity of computers.

Merely knowing that an artwork was AI-generated played a major role in people disliking it

It turns out that the context – merely knowing that an artwork was AI-generated – played a major role in people disliking it.

Another study published in 2023 in Computers in Human Behaviour showed similar results – people found art labelled as AI-made to be less awe-inspiring than human art. The authors attributed the aesthetic judgments to an anthropocentric impulse to defend human uniqueness, particularly in creative domains like art.

“We value the effort and the agency of the artist. So, when a machine creates the art, there is no “agent” in the same way. That could be a factor as to why AI art is devalued,” Anjan explains.

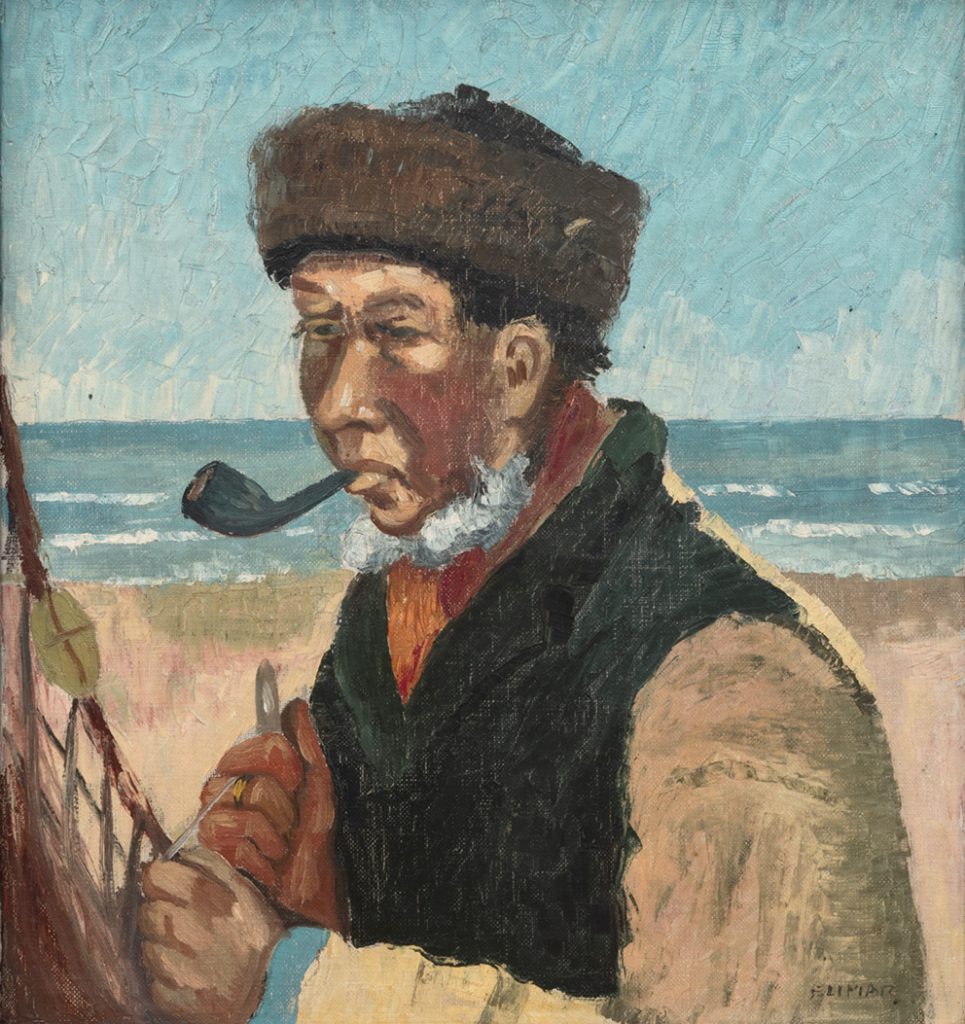

Interestingly, when participants observed machines “creating” the art, this negative bias reduced. Using a public experiment setup by French artist and scientist Patrick Tresset, participants in a 2018 study observed Five Robots Named Paul – a group of robotic arms with cameras on sticks, programmed to draw human portraits. These robots mimicked human behaviour, such as occasionally “looking” at the subject by moving the camera back and forth between subject and paper. Though this did not really help the robots draw better – they were programmed to draw from an image of the subject captured earlier – the movement invoked a sense of intentionality in the robots. Participants subsequently rated the robot-generated portraits higher than they rated other computer-generated art.

“We very easily attribute a mind to things that move with an intention,” explains Arun. “A great example is the Pixar lamp. It just sits there at first, and then it starts jumping. You can totally feel like it has a mind of its own.”

Other studies show that the negative bias is so strong that even when participants couldn’t visually distinguish between AI-made and human-made artworks, they still rate explicitly labelled AI art less favourably, especially on traits like artistic skill and monetary worth.

So, what happens when this labelling bias is removed? A recent study used OpenAI’s powerful image generative model DALL-E 2 to produce artworks in the manner of 36 famous artists. Participants were shown pairs of images – the original and the DALL-E-generated imitation in the same style – with no labels. Surprisingly, participants preferred the AI-generated art significantly more than chance. This also shows that AI art created by the latest models is not visually distinctive, so much so that the bias against AI art is eliminated in the absence of explicit labels.

Roots of bias

One reason that can explain this negative bias against AI art comes from studies of authenticity. “There are some studies suggesting that even children are oriented towards authenticity,” explains Anjan. “If you give children a choice between an original toy and a replica, they prefer the original.” The same bias for authentic objects is carried over in adulthood. Volunteers who were shown art labelled as fake or original overwhelmingly judged the originals to be more beautiful and valuable, even though visually, only an expert could tell them apart.

Our aesthetic judgments seem to be not just based on what we see and feel, but also on who we think made it. Whether it’s a robot arm mimicking human motion or a diffusion model trained on centuries of human creativity, perceived agency and authenticity deeply influence how we respond to art.

There are social parameters behind this bias, too. Many people feel that AI poses a threat to the livelihoods of artists. “Moreover, these AI companies are ignoring copyright laws,” says Kay. “And no one is holding them accountable.” Additionally, the datasets used for training these AI models largely include the work of male, Caucasian artists, causing the outputs to reflect the same biases and stereotypes, risking further marginalisation of underrepresented artistic styles.

Whether we like it or not, it seems like AI-generated art is here to stay. A lot of artists have embraced AI as a tool in their creative processes, such as Bangalore-based artist Amith Venkataramiah, whose Plastic Animals series, created with Midjourney, envisions marine life coexisting with plastic waste. There are now AI art exhibitions and auctions, and even plans for an exclusive AI art museum in Los Angeles, USA.

Perhaps, with time, who or what made the art won’t matter as much. “Think of all the art in churches across Europe or temples in India during prehistoric times. We admire that art, but we have no idea who created it, and it’s not even important,” says Anjan. “I wouldn’t be surprised if, over time, this bias begins to fade – especially in younger generations – as AI-generated art improves and the boundary between digital and analogue dissolves.”

For now, the bias against AI art seems to prevail. When Anisha and Kay were asked whether they would use AI in their art, they said:

“Never!”

“Artists want to think. We want to be sad about things and then fuel that sadness into creativity. AI takes away this creative process, so no.”

Sheetal Potdar has a PhD in neuroscience from JNCASR. She is currently the content lead at Diverge Communications and freelances as a science writer.

(Edited by Abinaya Kalyanasundaram, Ranjini Raghunath)