The scientist for social development

One morning in the early 1940s, 12-year-old Amulya Reddy received a letter from his uncle and hero, CGK Reddy, a marine engineer and political activist. The letter, written on a rough piece of paper, had arrived from the Madras jail where CGK was imprisoned for his anti-British activities. In the letter, he cautioned young Amulya against choosing a career based on hero-worship and urged him to pursue his passion. Amulya, who had been flirting with the idea of becoming a sailor like his uncle, began to introspect on his life’s true calling.

Being and becoming

Amulya Kumar N Reddy was born in Bengaluru in 1930. His early life was influenced by the Gandhian philosophy endorsed by his father, Narayana Reddy. Amulya’s interactions with towering figures like Jayaprakash Narayan, Achyut Patwardhan, and Rammanohar Lohia left a deep and lasting imprint on his personality. During his college years, Amulya found himself torn between his love for cricket and science. On one such occasion, he writes in his autobiographical piece (Citizen Scientist: The Amulya Reddy Reader): “I remember worrying about the electronic structure of the transition elements when I was fielding at square leg in an inter-collegiate cricket match. Not surprisingly, I dropped a catch.” Amulya believed that his interest in science was strengthened during his late teens through his close friendship with his schoolmate, V Radhakrishnan, and his cousin S Ramaseshan, the son and nephew, respectively, of Nobel Laureate CV Raman.

Hardship to horizon

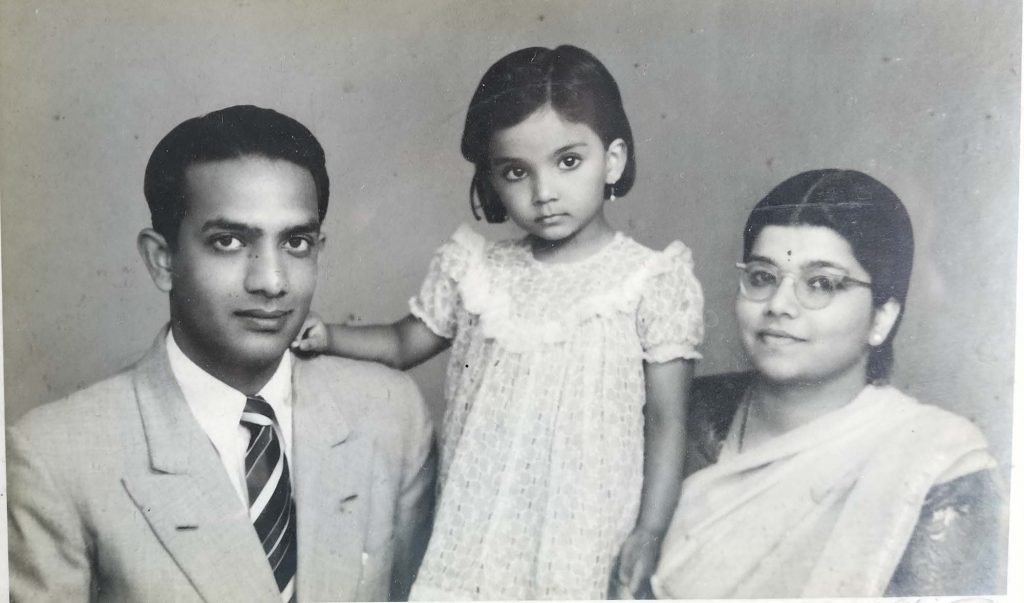

Amulya completed his schooling at St Joseph’s School, and his BSc (Chemistry) and MSc (Physical Chemistry) at Central College, Bengaluru. It was around this time that he and Vimala Pawar, his collegemate and friend, decided to get married. He took up teaching and became a lecturer in chemistry at Central College in 1951. Their first daughter, Srilatha, was born soon after. In 1955, Amulya set off for Imperial College London to pursue a PhD in electron-diffraction studies of the structure and growth of electrodeposits. Vimala joined him a few months later. Solely dependent on his meagre scholarship, Vimala took up a job to support their household, but she had to give it up soon after as their second child was born. To sustain his family, Amulya took a high-paying part-time porter’s job in the British Railways at London’s Waterloo station for two months. During this time of physical labour, he faced everything from humiliation to gratitude from the passengers whose luggage he carried. This experience opened a new perspective for him, one seen through the eyes of a labourer.

Amulya Reddy’s early life was influenced by the Gandhian philosophy endorsed by his father

Amulya earned his PhD and returned from England in early 1958. He secured a job as a Senior Scientific Officer at the Central Electrochemical Research Institute (CECRI) in Karaikudi, where he spent three years working mainly on the structure and growth of electrodeposits. His work at the CECRI attracted John O’Mara Bockris’ attention, a pioneer in the field of Hydrogen Energy System. He invited Amulya to work with him at the University of Pennsylvania (USA) in 1962. The two later co-authored the seminal two-volume series Modern Electrochemistry.

Amulya found deep satisfaction in his research. He worked on ellipsometry, the study of surfaces through analysis of the changes in reflected polarised light. His discovery of a new technique, chrono-ellipsometry, drew significant attention from the scientific community. This gave him much fulfilment and confidence as a scientist. This recognition ushered in many lucrative opportunities to work in the industry. But attractive salaries did not guarantee the freedom to choose what he wanted to work on. And the post-World War II gloom made him sceptical of science’s involvement in warfare. During one particularly disheartening occasion, he confessed to his wife that the work felt soul-destroying and that he was increasingly becoming mercenary. His wife, who was also feeling disillusioned with their life in America, suggested, “Let’s go home.”

Charting a new chapter

By the time Amulya returned to India in 1966, he had already earned a strong reputation as a research supervisor, thanks to his significant contributions to science, particularly in the field of ellipsometry. His co-authored two-volume textbook on electrochemistry was by now hailed by reviewers as the “bible of electrochemistry.”

These accomplishments helped him secure an assistant professorship at IISc. He joined the Department of Inorganic and Physical Chemistry in 1967 and began his research with a team of students. In the beginning, progress was slow due to limited funds, and experimental facilities had to be built from scratch. Gradually, things improved, and the work picked up pace. He quickly realised that a majority of the fundamental discoveries in the field of electrochemistry were already made and began to steer his research towards an applied direction.

The shift within

It was during his time at IISc when an event altered his way of thinking. In a lecture, economist CT Kurien, who was then working at the Madras Christian College, argued that poverty had increased with industrialisation. His persuasive argument shattered Amulya’s faith in the Nehruvian dictum: “science and technology -> more industrialisation -> less poverty”. A period of intense introspection followed.

He took a step towards unpacking this problem and presented a paper titled: “An Asia Science to Combat Asian Poverty”, at the One Asia Conference in Delhi, organised by the Press Foundation of Asia. He argued that the industrialisation-poverty nexus arises from the capital-intensive, labour-saving pattern of industrialisation based on imported Western technology and that an attack on poverty (in India) required a different science and technology, an “Asian Science”.

The paper attracted favourable attention. Subsequently, he was invited as a discussant for the National Committee of Science and Technology’s document on “An Approach to Science and Technology Plan”. In the discussion, he insisted that India was a dual society with islands of elite affluence amidst an ocean of poverty, the inequality driven primarily by inadequate income-generating employment in the rural countryside, and that such employment would not come from capital-intensive industrialisation.

Amulya resolved to focus on developing technologies for rural India

As a consequence of this presentation, a large number of faculty members from IISc agreed with his argument and expressed their desire to contribute to alternative science and technology. It was at this point that Amulya resolved to focus on developing technologies for rural India. He quit electrochemistry, walking away from his life’s work without a backward glance. He did not want to have a fallback option when things got difficult in his new venture. Such was his conviction and belief in his path.

Reframing scientific focus

In 1974, Amulya Reddy established the Centre for Application of Science and Technology in Rural Areas at IISc. The centre became better known by its acronym ASTRA, which means ‘weapon’ in Sanskrit. The name was a deliberate effort to underline the focus of the Centre’s multidisciplinary efforts, which drew on the expertise from various science and engineering-oriented departments. However, ASTRA was not without their detractors, attracting scorn from several prominent figures within the Indian scientific establishment. Despite these obstacles, ASTRA’s work began to receive national and international recognition and appreciation. While awarding the Ravindra Puraskar to Amulya in 1978, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi is said to have exclaimed, “It must have required rare courage!”

Early projects of ASTRA focused on rural India-specific critical areas such as bioenergy, fuel-efficient stoves, low-cost housing, and clean water. The Ungra village in Karnataka became a living laboratory for ASTRA’s early innovations, where rural communities benefited from biogas energy solutions derived from agricultural waste and biomass. This programme not only provided energy for domestic use but also supported street lighting, irrigation, and small-scale industries.

“Amulya Reddy did not want technological innovations to be handed down to the villagers as products, but he wanted them to participate in the process,” recalls HN Chanakya, who joined ASTRA in the early 1980s and started his work in Ungra. He recollects the challenges and failures in setting up new technologies before they achieved success. Even gaining the trust of the locals took significant time and effort. But once the people understood the value, they wholeheartedly cooperated.

In 1975, Amulya became involved in establishing the Karnataka State Council for Science and Technology (KSCST), working alongside MY Ghorpade, the then Finance Minister of Karnataka, and Satish Dhawan, the then Director of IISc. The primary aim of KSCST was to bring government and scientific institutions together to address the problems of poverty in Karnataka. The idea was that ASTRA would concentrate on the generation of technology and KSCST would focus on the dissemination of the solutions. KSCST, in the later years, became a model for other state councils.

In the same year, Amulya took a sabbatical and went to Nairobi, Kenya, to work with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). There, he involved himself in the development of the conceptual framework for environmentally sound and appropriate technologies. It was during this stint that he formed his views on concepts such as development as a process of economic growth that is directed towards equity and the satisfaction of basic needs, starting with the needs of the neediest; empowerment as the strengthening of self-reliance; and environmental soundness as living in harmony with the environment.

He held on to these learnings for almost two and a half decades. However, when the controversy surrounding the Narmada valley projects came out (which centred around the Sardar Sarovar Dam and other large dam projects on the Narmada river, primarily due to the displacement of communities and environmental concerns), he accepted that the benefits of development projects must start with the people at the project sites and radiate outward. Otherwise, the very people at the epicentre of the projects become the victims of development. He also believed that women are crucial agents in development activities. Engenderisation became an important element of his idea on development from thereon.

At the turn of the century, Amulya Reddy was conferred with the prestigious Volvo Environment Prize. The prize recognised his outstanding collaborative work since the early 1980s in developing a new policy-driven approach to analysing global energy needs and identifying ways to meet them in the early decades of this century.

Passion and purpose

“There was little distinction between his professional and personal self,” says Srilatha Batliwala, Amulya Reddy’s eldest daughter, an accomplished advocate and women’s rights scholar. Srilatha remembers him as gutsy, steadfast in his beliefs, and with an unwavering commitment towards equality, be it gender, social or economic. He was also blessed with a sense of humour and could bring levity to serious situations. At home, he nurtured lively discussions on social issues, and their dinner table conversations featured nationalism, advancing social justice, and contribution to nation-building. Srilatha remembers how she once sniggered about a romantic relationship between two girls during her time at school in the late 1960s. Amulya disapproved of her contempt, saying each person has the right to love whomever they want. This continues to serve as a guiding reference in her work as a gender activist.

Srilatha remembers him as gutsy, steadfast in his beliefs, and with an unwavering commitment towards equality

Amulya always cautioned his three daughters that “if you accept discrimination against anyone because of who they are, you have to be ready to accept discrimination against yourself too.” He was agnostic, troubled by the divisive role caste and religion played among citizens. Cricket was the only religion that he partook in.

A lasting legacy

ASTRA was renamed the Centre for Sustainable Technologies (CST) in 2003 in recognition of its growing focus. Since Amulya’s initial efforts, CST has emerged as a leading force in India’s sustainability landscape, developing a range of technologies that tackle both local and global challenges. Its research spans critical areas including climate change mitigation, green buildings, solid waste management, and ecotoxicology. As CST marks its 50th anniversary in 2025, it remains dedicated to advancing science and technology to empower communities and meet the evolving environmental and societal challenges of the future. Today, the centre’s focus is on water purification, waste-to-energy technologies, and energy-efficient construction, highlighting its integrated and holistic approach to sustainability.

Amulya Reddy passed away on 7 May 2006. Through his steadfast dedication to sustainability, equity, and technological innovation, he redefined a key purpose of scientific inquiry – placing people, especially those who are marginalised, at its core.

“Even till his last days, my father refused a kidney transplant, saying that he would not take a poor man’s organ to extend his life,” says Srilatha.

(Edited by Sandeep Menon)