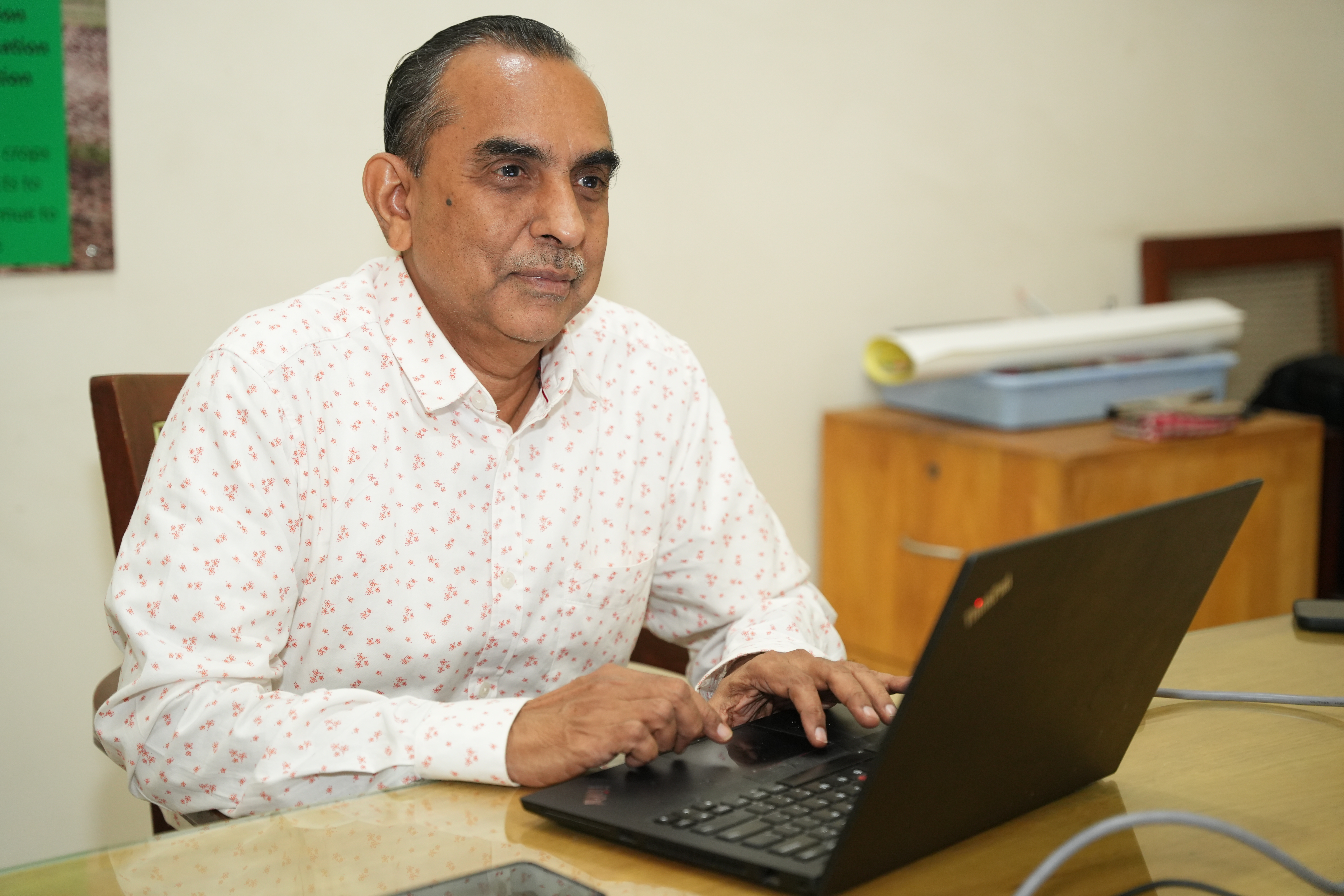

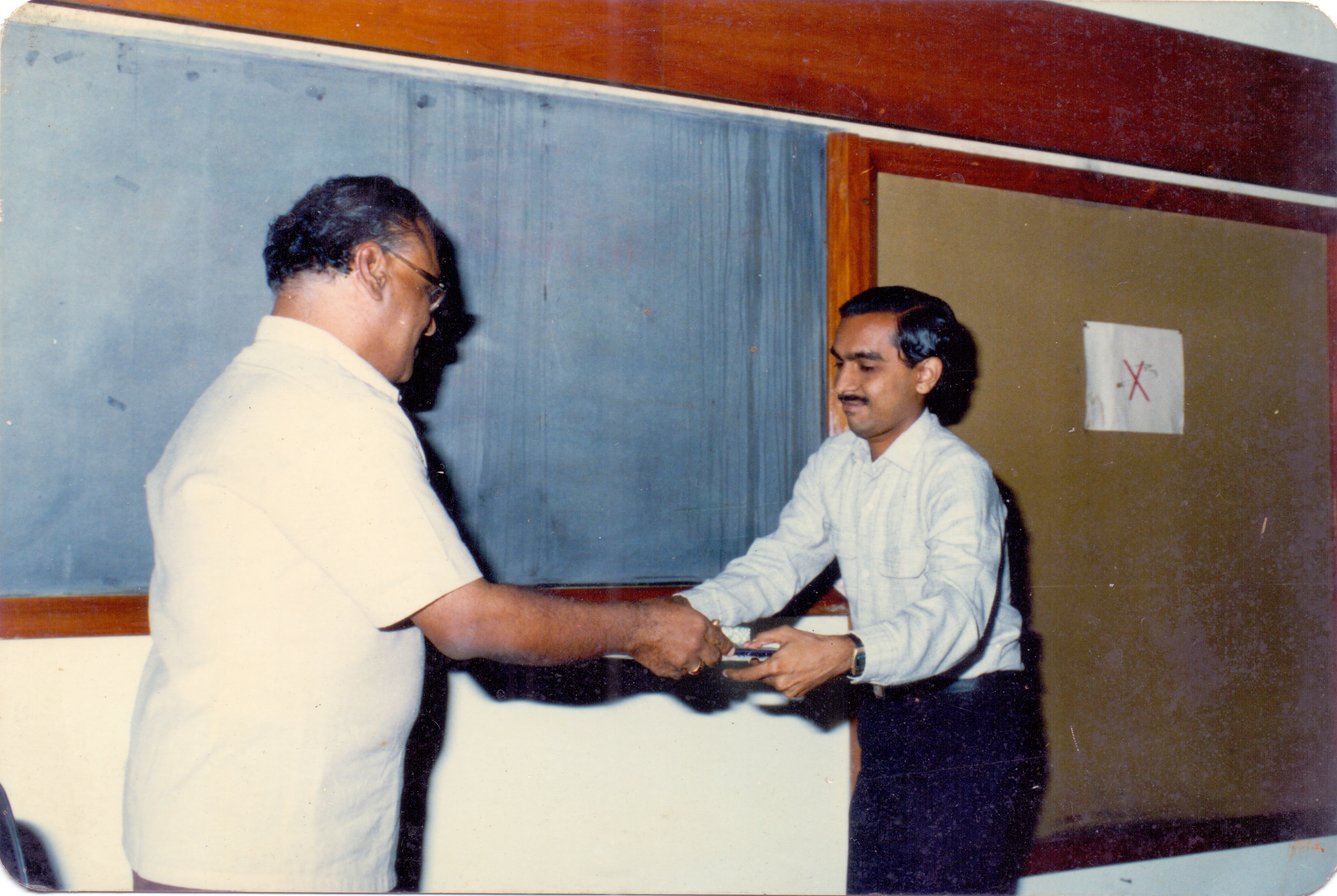

Yadati Narahari leans over his desk, turning his computer screen around as he shows an image. It shows a group of people standing side-by-side staring into the camera. It is an image that Narahari holds with great regard, one – he feels – encapsulates his time at IISc. “This is six generations of researchers and scholars,” he explains. “This is my guru, his guru, me and the ones that I taught.”

Narahari has spent over four decades at the Institute. After joining as a student in the late 1970s, his time at IISc saw him scale heights as high as Dean of his Division, Director of a major centre, and the driving force behind the digitalisation of the Institute, all while producing 29 PhD scholars, powering his laboratory and research work in game theory, mechanism design and AI for social good, and publishing several books and papers, with the help of his wife and ‘hidden author’, Padmashree.

Narahari sat down with CONNECT to talk about his journey in academia and the Institute’s evolution, in which he played a major role.

You have spent 45 years in IISc. Can you talk about your journey of getting into the Institute and then continuing on?

The thing is, it’s very difficult to get into IISc. It is also very difficult to get out after you’re inside because you fall in love with it.

Sometime in 1978, I was in my final year of BSc at AES National College in Gauribidanur, in Chikkaballapur district. I did not even know of the existence of IISc at that time. My dream was to finish my BSc, apply for MSc in mathematics at Central College, Bangalore and then go back and teach at AES National College.

It was my brother’s father-in-law, Anant Rao, who suggested that I apply to MSc mathematics at IIT Madras and for the three-year BE programme, which was a post-BSc programme, at the so-called Tata Institute or Indian Institute of Science. I cleared both the exams. That’s how I came here in August 1979.

I did my BE here for three years in the ECE Department and enjoyed the course work. There was healthy competition among the 30 students. From 1982-84, I did ME in the Department of Computer Science and Automation (CSA). It was called the School of Automation at that time. Then in 1984-87, I finished my PhD and joined here as a scientific officer, became a lecturer in 1988, an assistant professor in 1989, associate professor in 1995, and full professor in 2001.

In December 2009, I became the Chairman of the Department of CSA. In 2014, I became the Chairman of the Division of Electrical Sciences (subsequently, this became the Division of Electrical, Electronics and Computer Sciences or EECS). I was Dean of EECS till July 2021. During 2022-23, I was officiating as the Director for the Center for Brain Research (CBR). During 2016-21, I was also Chairman of DIGITS. My innings closed on 31 July 2024. I am now an honorary professor until July 2029.

Was there ever a time when you could have left the Institute?

At IISc in general, and in the departments I have worked in, the ecosystem is wonderful. When you are a student, you look for some excitement in the learning process and inspiration from your professors and instructors, and that was very much there. The professors here were very accessible.

At the end of my BE, I got a job at Wipro. In fact, my HR interview was taken by none other than Azim Premji [the former chairman] because it was a small company then. But I wanted to continue here.

Then, I was an ME student for two years here. My dream job was at the Indian Space Research Organisation. So, I applied only to ISRO and got a job where they offered me two increments as well. It was my dream job, but then, the attraction of PhD was there.

How has the Institute evolved during your time here? Not just from an educational perspective but a cultural one as well.

Universities are where the future of science and technology is supposed to be envisioned, where future leaders of the nation are trained. So, it is very important for the institution to be aware of what is happening at the global level. Maybe the slope of progress is much higher in recent decades compared to earlier. Because I have been here for 45 years, this change is more like an evolution for me rather than abrupt.

I was in the ECE department and even in those days, the Institute used to have a large number of electives, a progressive initiative. I ended up doing a lot of electives from the computer science department. In the early 1980s, this was an iconic department in the Institute. The department was started in 1969, and it was, in some sense, the first experiment of interdisciplinary work. The faculty members were from many departments like electrical, mathematics, aerospace … some came from outside. It was supposed to work on Grand Challenge Control problems, like those that ISRO, DRDO, and the Department of Atomic Energy solve. So, the department was started with a very specific purpose of automation and control. Gradually, it evolved into the computer science department.

In 1971, it was this department (CSA) that introduced an ME in computer science for the first time in India. The Institute was also the first to start an MTech programme in artificial intelligence, about six years ago. The Institute and the departments have been at the cutting edge.

How has teaching changed both in methods and technology over the years?

It has changed quite a lot in recent years. In my own teaching, there has been a continuous evolution, but one thing that has remained constant is that I have always believed in blackboard teaching, from the very first course that I taught in 1987 to the most recent.

Post the pandemic, I was teaching using the slides I had prepared during COVID-19. Midway through the course, I took a student poll. ‘Do you want me to continue with teaching from the slides or do you want me to start using the blackboard?’ 90% said blackboard. So, now I teach the Game Theory class only on the blackboard. In the algorithms and programming class, I am experimenting with teaching from slides because the class has 150 students and there are display monitors throughout the classroom so they can see more easily.

The way we teach has also dramatically changed over the last two or three years, because of the emergence of modern AI tools. You get fantastic code, which is almost flawless [using AI tools]. I co-teach a course with Professor Viraj Kumar, and we decided to encourage students to use AI tools as a part of learning. We teach all the foundations. The programming assignments are of two types. One where they are not supposed to use AI tools and one where they are. We also give them programs generated by GPT-4 with subtle flaws and ask the student to find out if it works for all inputs.

The way we teach has dramatically changed over the last two or three years, because of modern AI tools

Speaking about AI, there is a lot of concern about this evolving tech. What is your take on this?

Every modern technology has dangers associated with benefits. It’s very important that you derive the benefits to the maximum extent and take the measures required to prevent dangers. The degree to which AI has started influencing almost every walk of life is unprecedented. But I think this trait was there with every modern technology.

Is the AI revolution going to be like the industrial revolution?

It depends. For people working in areas like natural language processing or large language models, it has been a very gradual process. But because of AI’s dramatic influence and innovations, 90-95% of people feel that it is a revolution. What is dramatic is the pace at which almost every field is getting influenced.

Can you talk about the Game Theory Lab?

Game theory is the science behind microeconomics. It is the analysis of games, which are basically strategic interactions between rational and intelligent individuals. We study how these interactions will happen and how they are driven by individual interests.

Every agent tries to do individual optimisation and maximise his or her own utility. But if everybody is individualistic, then societal goals may not be met. Game theory is all about understanding the effect of individual strategies on societal goals.

The question is: Can we design games so that the strategic interactions among the different players will result in social objectives? This is called mechanism design.

Game theory was developed by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern in the 1920s. Seventy years later, there was a marriage between game theory and algorithms, and the branch of algorithmic game theory was born. Many faculty members in the CSA department, starting from me, began working on algorithmic problems in game theory.

Recently, I have found that some of these principles, along with artificial intelligence, can be used in solving some problems in agriculture as well. The project started from a chance meeting with Dr PV Suryakumar from NABARD (National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development). It was not easy to recruit students [for it] because they wanted to work on projects that helped them fetch a good job. I know that all of them will be interested in deep learning. I was using deep learning for many of these problems. So, I called it deep learning-based crop planning, deep learning-based crop recommendation, deep learning-based crop price prediction, and so on. This was a mechanism design for attracting students!

We have also implemented our learnings, where we actually demonstrated our algorithms through mobile apps.

Could you tell us about your role in establishing DIGITS?

It was the brainchild of the then Director, Professor Anurag Kumar. There was a unit called TINA: Telecom and Internet Access. In 2015, we wanted to start a separate IT office for the Institute. I coined the name Digital Campus and Information Technology Services or DIGITS.

There were two major problems we wanted to fix. One was email and email servers. IISc was on the educational and research network (ERNET) and every department had an email server, so it was a decentralised operation. We wanted to centralise it. The other one was that there were 16 different databases in the Institute. If you wanted some information about a student, you would get partial information from these databases or a subset of them. There were inconsistencies. For example, when an MTech student becomes a PhD student, one database will say that she is still in MTech. Another will say she is doing PhD, and a third – because the degree certificate for MTech was issued – would say she has left. We wanted to have a single source of truth.

And of course, associated with that there were administrative processes – HR, purchase, finance, projects, and security processes – which we wanted to streamline.

The first objective, namely the email service, was solved by using Microsoft Azure and a single email gateway from the Institute. It was a complex operation because we had to migrate 6,000 to 7,000 users to the new system.

For the second one, it was a major decision. The DIGITS core team would have weekly meetings with the Director. By 2016, it was decided that we would go in for an enterprise resource planning package. After much deliberation and an elaborate process, SAP was selected. We decided to have somebody to help us implement SAP and Wipro won the contract in competitive bidding. With their help, we started the implementation of SAP from 2017. In 2019, we went live. We went live with Student Lifecycle Management in 2020.

It was tough. I am a person who always had maximum goodwill from almost everyone in the Institute and for those three years, I lost all of it (laughs).

You have had several roles and worn different hats …

Little did I imagine that I would be officiating as Director of the Centre for Brain Research because brain research is not my area. My job was a great challenge: to walk in the shoes of Professor Vijayalakshmi Ravindranath, who built CBR brick by brick. Someone was required to maintain the momentum and I was contacted because I had administrative experience. I was on the governing board of CBR for quite some time ever since its inception. I was there as the Director for about 19 months; I maintained the momentum of the place and ensured that the new Director was selected.

Whenever the Institute wanted me to do something, I rarely said no because the Institute has given so much to me.