Why it matters and what are the challenges confronting science historians

A quick internet search on the discovery of helium will be dominated by results that claim that helium was discovered by the French astronomer Pierre Janssen.

“While observing a solar eclipse in Guntur, India, on 18 August 1868, Janssen noted that the spectral lines in the solar prominences [large, bright features that extend outward from the sun’s surface] – were so bright that they should be easily observable in daylight,” according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

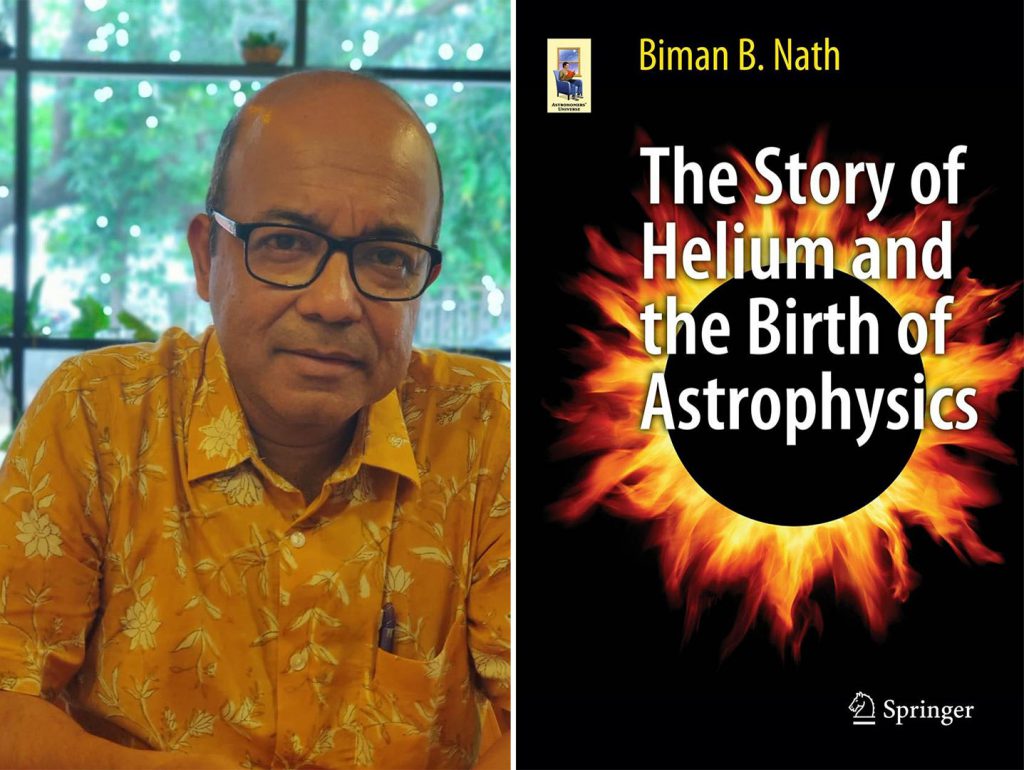

“This is all wrong,” says Biman Nath, a physicist at the Raman Research Institute in Bangalore and a science historian. In his book The Story of Helium and the Birth of Astrophysics, published in 2013, he writes that the discovery of helium was more of a collaborative effort that involved many other scientists including Joseph Norman Lockyer and Norman Robert Pogson. The book, a result of a decade of work studying research papers and letters from scientists, traces the history of helium, an element essential for high-speed computing and space exploration, but in short supply on our planet even though it is the second most abundant element in the universe.

Why science history

Besides correcting a popular but incorrect notion of how helium was discovered, Nath’s book helps the reader understand the process of scientific research. Elaborating on the importance of science history, Richard Creath, a philosopher of science, goes even further. In his 2009 article published in the Journal of History of Biology, he argues that the history of science is integral to science itself. “The history of science is an essential part of each science,” he writes. Thomas H Grainger, in his 1956 article in the journal Improving College and University Teaching titled ‘Why Study History of Science’, adds that studying the history of science helps “exhibit the sense, purpose, and reasoning to science.”

Nath, who has also written a biography of the well-known Indian physicist and pioneer of India’s nuclear programme, Homi J Bhabha, also makes a broader case for studying the history of all human endeavours, including science. He believes that understanding history allows us to stay connected to our community and increases social awareness. “We belong to the community and cannot be devoid of any connection to society.”

Biman Nath believes that understanding history allows us to stay connected to our community and increases social awareness

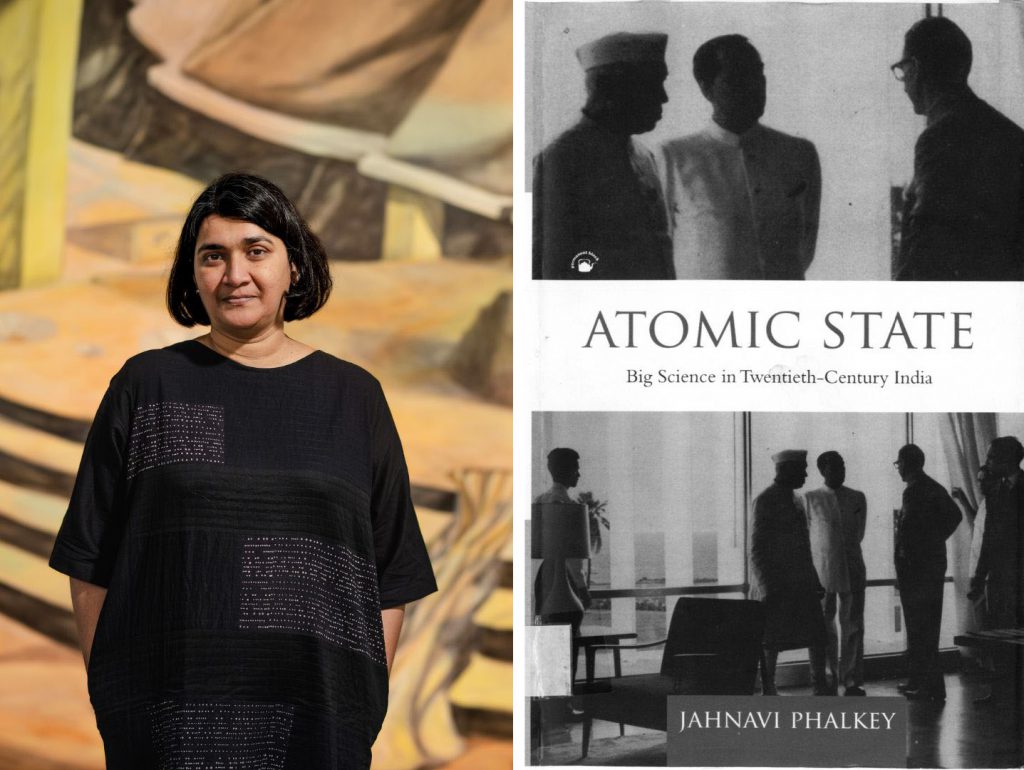

Jahnavi Phalkey, a historian of science, argues that knowing the history of science also allows us to understand how science developed over time. Now the Director of Science Gallery Bengaluru – a space for public engagement of science – she illustrates her point using the example of astrology, which was once considered a legitimate science. “Astrology at some point was not a pseudoscience.”

According to her, as in the case of astrology, studying science history helps us understand how and why the boundaries between science and non-science have been drawn over time. She points to yet another infamous idea that was once considered “scientific.” “Scientists found that women’s brains were different to men, and therefore interpreted that women were intellectually and cognitively less capable when compared with men overall. We have seen how this has been corrected over time.”

However, while it is the job of a science historian to reveal how a particular science developed, Jahnavi thinks that it is not a historian’s job to judge what is true and not true. “It is a historian’s job to understand why something is said to be true and what is the argument behind the claim.”

Challenges of doing science history in India

Jahnavi did her PhD in science history from the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. For her thesis on the history of nuclear research and education in India, she needed archives for photographs, letters, and official documents related to her research. But, as she found out, in India, accessing historical material was tough. “In my graduate programme, my colleagues who were studying in the United States or countries in Europe broadly identified their questions and then they knew the number of archives they would need to go to, and then they would go to those archives for a six-month time period to get the documents they wanted.”

But for scholars working in India, “it is the other way around,” she says. “For anyone to find interesting and important records in the archive, it might take years,” as most Indian research institutions and universities do not have an institutional archive. “When I started, the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research [TIFR, Mumbai] Archive was the only one that was systematically working.” The IISc Archives, she adds, was working but was in the initial stages of being set up.

Personal papers of scientists, crucial for science history research, are not easy to get hold of

Jahnavi alludes to yet another bottleneck for doing science history in India – the lack of appreciation of the importance of our science history. “Most others do not even keep the papers once the person passes away,” says Jahnavi. If they are not thrown away, at times, important scientific papers tend to lie around in the houses of researchers or their family members after they have passed away. She even chanced upon documents related to ballistic missiles in the house of a scientist.

Jahnavi also points to another fundamental problem for research in science history in India – there are very few science historians. “There is no university in India that offers a history of science degree.” But even if they do get trained, they are confronted with the problems she encountered in her research. “You can train people in history, you can train them to think historically, but they are going to need archives.”

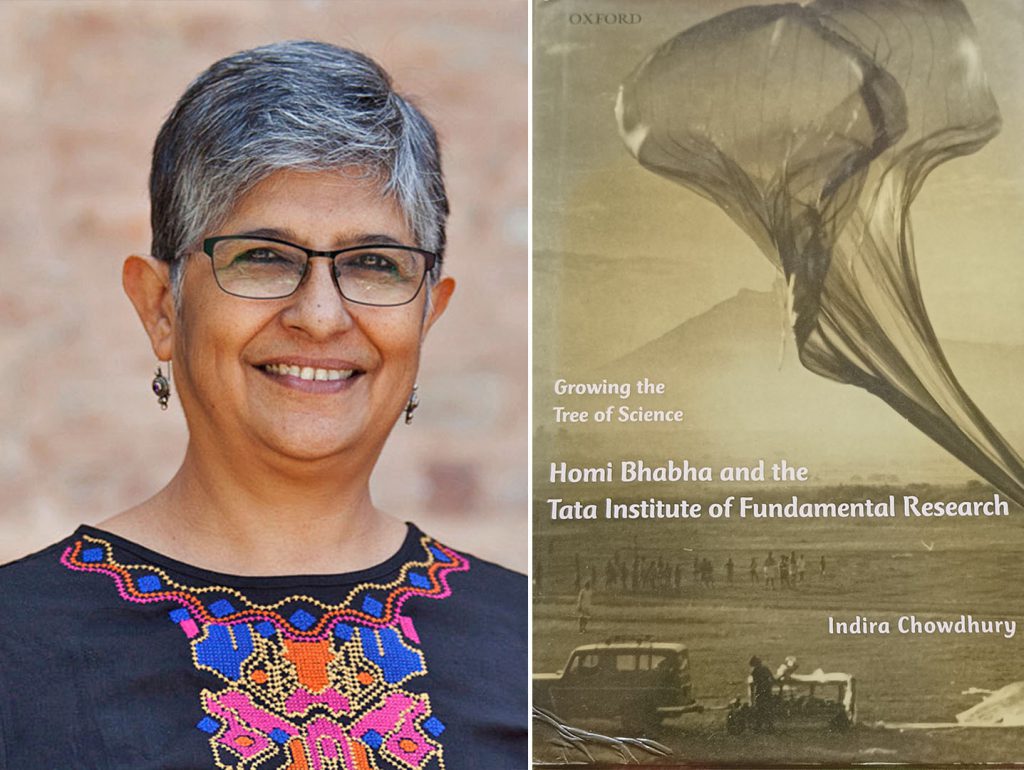

Indira Chowdhury agrees with Jahnavi’s views partly because of her own struggles. Indira, a historian of science and an archivist, until recently headed the Centre for Public History at the Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology in Bangalore. Indira’s doctoral thesis focused on masculinity and the idea of nationalism, which she did from the School of Oriental and African Studies, London. It was during her PhD that she crossed paths with the history of medicine. She was particularly interested in the history of birth control in India. But she too struggled to find Indian archives that housed material useful to her research. In fact, many documents related to her work were sitting in archives in the United Kingdom. “At that point, I had felt that it would be really good to have lots of archives in India that had to do with the post-independence period.” Yet another concern that Indira has is that archives in India seldom have institutional policies that make it conducive for science historians to carry out their research.

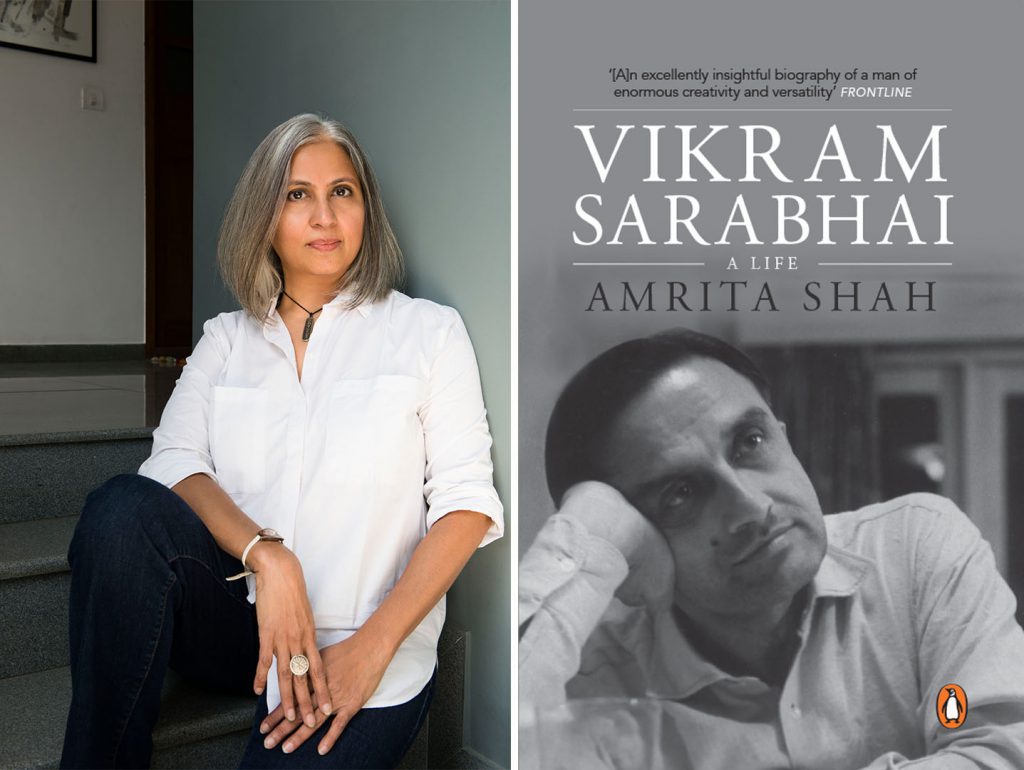

Amrita Shah, a well-known journalist, too faced several obstacles while she was researching the life of space scientist Vikram Sarabhai, about whom she wrote a biography. “There was no full-fledged biography of Sarabhai. His name was not mentioned in any accounts of modern India that I came across.”

Sarabhai’s official archivist gave Amrita only Sarabhai’s speeches which had already been published and some tributes after his death, and showed her a few pages of Sarabhai’s diary.

“ISRO had some oral histories that were extremely helpful,” Amrita adds.

Looking ahead

Science historians are unanimous in their view that we should have more institutional archives to carry out research and tell stories about Indian science and scientists. “Archives contain primary sources of information that can give us insight into the actions and decisions of governments, institutions, communities and individuals, as well as hold our memories,” writes Deepika S in the June 2022 issue of Connect, explaining the role of an archive. Indira says that at a time when propaganda machines work to disregard a scientific past and mix the mythical past, archives are important spaces to make people aware of science which will help them understand their past as opposed to getting a convoluted view of the history.

Jahnavi believes that all relevant research documents that belong to a scientist should ideally be in an institutional archive or museum.

Indira also makes the case for not just having traditional archives, but also oral archives. According to her, archiving oral histories will provide information that goes beyond facts. They reveal how one arrived upon the decisions they made. “I take a very long view of the history and I feel the more the material we put in the archives, the more we make people aware of how we can understand the past,” stresses Indira.

Science historians are unanimous in their view that we should have more institutional archives to carry out research about Indian science and scientists

Indira believes that more scientists should take an interest in understanding the importance of archiving. “My request to all scientists is to learn a bit about archiving, no matter how busy they are.”

Jahnavi, however, cautions against merely having an archive for the sake of it without having a coherent institutional policy about how to establish and manage an archive.

“Institutions need to maintain their archives, and that doesn’t mean just pushing files and papers into cupboards as they were found. They need to be organised, indexed, conserved, and furthermore, made accessible to the researcher, filmmaker, journalist, artist – or for that matter to any interested citizen.”

The importance of a meaningful policy for collecting material and maintaining an archive is a view echoed by Indira. Indira herself has been associated with several institutional archives including the archives of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research which she helped set up. Amrita too makes the case for more institutional archives when she says that it is imperative that we find ways of preserving “the history of science, the history of art, the history of knowledge.”

Jahnavi maintains that we need more training – for both archivists and science historians. “We need training, and we need archives … without those two things not much will happen in a credible way.” It is through these efforts, according to her, that a good “ecosystem” of science history can be built and help illuminate our scientific past. This will go a long way in helping us understand larger questions about why we are what we are, how we got here, and where we are headed as a society.